China’s authoritarian trend meets resistance in East Asia and the Pacific

Table of contents

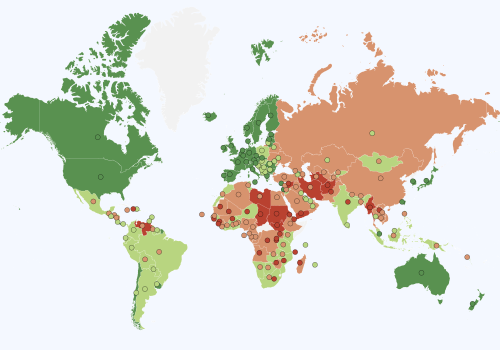

Evolution of freedom

The trends shown in the Freedom Index match some key historical events that impacted the region’s trajectory. The wave of democratization that followed the Soviet Union’s fall in 1988–89 peaked during the Asian financial crisis of 1997–98, before stagnating for several years afterwards. Despite, or perhaps because of Indonesia’s transition to democracy in the years after 1998, the overall regional political picture remained relatively constant, with democratic nations sustaining their democratic status and authoritarian countries largely doing the same. This relative stasis led to a plateau in the Freedom Index between 2000 and 2010. The visible improvements in political and economic freedom from 2012 onward are attributable to the quasi-democratic transition in Myanmar, a country previously governed by a military junta for seven decades, as well as greater political dynamism in Malaysia and the region’s overall continued economic liberalization.

The early 2000s also marked an era of substantial economic growth in China, accompanied by limited political liberalization. This trend toward liberalization has taken a dramatic downturn since 2013, which is associated with the rise of Xi Jinping as the paramount leader of China and his hardline approach to governance. This reversal, together with the 2021 coup in Myanmar, has exerted significant downward pressure on freedom across the region. This downward pressure, if weighted by China’s economic and demographic size, would show up even more clearly on the Freedom Index during this period. It is also crucial to acknowledge that the aggregate figures may actually understate the extent to which overall regional freedom was and is under pressure due to China’s internal policy shifts and its external influence over the democratic and economic development of neighboring countries.

On economic freedom, it is striking to observe the remarkable progress made on women’s economic freedom, emerging as a significant positive trend within the broader context. This progress has been led by several countries that recognized the economic potential inherent in women’s participation. This was a priority of the White House-led Women’s Global Development and Prosperity Initiative—that I was a part of—emphasizing the benefits of enhancing female workforce involvement and dismantling regulatory barriers. Such measures were projected to foster substantial economic growth, and by some metrics nearly all economic growth in the region can be attributed to the dramatic increase in women’s economic participation.

Comparatively, other factors like trade freedom, property rights, and investment freedom have shown only marginal improvements over the sample, underlining the pivotal role of women in propelling economic prosperity. This aspect becomes even more profound when considering the exponential economic growth experienced by these countries in the past thirty years. This warrants similar scrutiny to determine if this trend remains consistent on a global scale. There seems to be an undeniable correlation between women’s participation in the workforce and the stimulation of economic growth and prosperity worldwide. While this trend is an overall positive one, given the regression of women’s rights in China under Xi Jinping—a phenomenon that has accelerated in the past five years—we should expect to see a correlating loss of economic momentum across the region. Again, if these numbers were weighted by population and size of economy, China’s regression would wipe out most—if not all—of the recent and projected gains made by other countries in the region.

Overall, recent developments in China reveal a concerning pattern of exerting downward pressure on women’s rights, both politically and economically, in response to demographic challenges. This realization underscores the fragile nature of women’s economic progress, particularly when subjected to external pressures or anti-freedom regulatory changes. The potential impact of these trends could manifest as a significant downward force, consequently jeopardizing decades of progress. The adverse implications could extend to critical areas such as poverty alleviation, health outcomes, environmental sustainability, and educational attainment for entire economies, given the historically strong correlation between these socioeconomic indicators and the economic advancement of women.

On legal freedom, the graph shows periods of marginal improvement followed by stagnation and subsequent regression. Notably, while there appears to be a regional convergence around “legal clarity” and “bureaucracy and corruption” between 2014 and 2018, China sees a sharp divergence on these two issues starting around 2014. These trends coincide with Xi Jinping’s far-reaching anti-corruption campaign at home and the launch of the “Belt and Road” initiative abroad. This period also witnessed a simultaneous shift in China’s legal landscape, namely the reversal of prior, admittedly modest, efforts to cultivate nominally independent judicial and legal institutions that were somewhat separate from the influence of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). With China’s explicit shift from “rule of law” to Xi’s “rule by law” since 2013, law is increasingly utilized as a tool for the CCP to control people and institutions, rather than establishing an independent legal space. This reconsolidation of party control over state institutions wiped out twenty years of progress, with widespread consequences for the rule of law—particularly around the sanctity of contracts and other foundations of economic progress. This increasingly unpredictable legal and policy environment in China has had economic consequences, including a dramatic decline in foreign direct investment and an increase in capital flight.

In many countries in the region, legal freedom is intricately linked to political freedom, particularly in nondemocratic nations. Several of the region’s economies have attempted—with varying degrees of success—to disaggregate economic freedom from political freedom while maintaining a stable and predictable business climate. Singapore is by far the most successful example, but its success is generally considered an anomaly attributable to its small size and the highly competent nature of its ruling elite. Singapore’s long-ruling People’s Action Party (PAP) prizes the country’s reputation as a rule-of-law jurisdiction that maintains high standards and predictability in its banking, legal, and other economically important sectors. It is also worth noting that Singapore has benefited from a loss of confidence in Hong Kong as a regional financial hub. Even as the PAP has allowed a greater degree of personal freedoms in recent years—and maintains the formal aspects of democracy, such as multiparty elections and a functioning legislature—the Lee family dynasty continues to wield enormous influence on politics and policy. By contrast, in Myanmar, promising economic reforms that spurred dramatic economic growth during the 2012–21 “hybrid period” were also aimed at undoing decades of mismanagement by successive military regimes that ruled through extraction, corruption, and violence. Since the February 2021 coup however, the combination of political repression and armed conflict in Myanmar, together with the return of extractive military mismanagement of the economy, has wiped out a decade of substantial economic growth and plunged the country backwards across all freedom and prosperity metrics.

On security, the anomalies in certain periods can be attributed to global events such as the “war on terrorism” which drove legal uncertainties in countries like Indonesia and Malaysia. The period between 1998 and 2002 witnessed particularly intense geopolitical shifts in the region, including the establishment of Timor-Leste and Indonesia’s overall positive trajectory. However, while there have not been similarly earth-shaking transitions in recent years, the region has experienced an increased level of volatility from military coups in Thailand and Myanmar, political disruption in the Philippines and Malaysia, increasing authoritarianism in Cambodia, and China’s military adventurism towards Taiwan and grey-zone antagonism in the South China Sea, all of which have negatively influenced the overall political and legal landscape.

From freedom to prosperity

Consistently maintaining a 3-point lead over the global average in terms of overall prosperity from 1995 to 2019, the East Asia & the Pacific region has shown a remarkable level of economic resilience despite an often tumultuous political environment. With significant progress since the early 2000s, the average income score in the region has surged, positioning the region 5.5 points ahead of the global average by 2022, when the two had been roughly equal in the year 2000.

But it is also worth noting that, despite the frequent invocation of “the East Asian miracle,” the overall prosperity score for the region is parallel to the global trajectory, displaying a proportionate trend rather than a significant disparity. We know that over the past three decades China alone has contributed close to three-quarters of the overall global reduction in the number of people living in extreme poverty, but looking at overall prosperity brings a new light to that progress in the region. As in other regions, there is a complex interplay between economic growth, inequality, educational attainment, and minority rights that defies easy categorization or explanations.

As we see in the data, rapid economic expansion in nondemocratic countries can lead to progress on education and health indicators, but often coincides with growing income inequality. Environmental sustainability also appears to be a critical area for attention, as the region shows much slower progress than the global average on the environment indicator. This issue deserves a greater focus given the region is home to some of the largest and fastest-growing carbon emitters in the world and some of the planet’s most important and vulnerable areas for biodiversity, climate risk, and the blue economy.

The region also features a notable trend in the context of minority rights, where we see a lot of fluctuation. After a significant positive surge in recognition and protection following the end of the Cold War and the dissolution of the Soviet Union, events such as the 9/11 attacks, the war on terrorism, and global financial crises appear to have contributed to periods of stagnation and eventual regression. While international efforts to bolster human rights mechanisms focusing on minority rights intensified, the global trend in terms of actual impact remained mostly negative, and we see only minimal and isolated improvements in the region. Yet a closer examination reveals the intrinsic connection between minority rights and inequality. Looking at these two indicators together allows for a more nuanced understanding of the challenges faced by marginalized groups within societies experiencing rapid economic prosperity, and raises a number of interesting questions about sustainability and internal stability for both developing and developed countries in the region.

On education, the fact that the region is in line with the global trend is surprising, and could be considered something of a failure for a region that has been prioritizing progress on educational attainment for decades. Understanding this phenomenon would require a more nuanced evaluation of the region’s educational policies and practices, as well as the impact of social mobility and other economic factors.

The future ahead

The impact of China’s actions within and beyond its borders holds significant sway over the political and economic dynamics of the region. While the unweighted data offers a tantalizing glimpse of this impact, a weighted analysis that reflected China’s economic and demographic heft would likely further reveal its profound influence on political and economic freedoms across East Asia & the Pacific. The practices emerging from the People’s Republic of China, particularly the establishment of Beijing-facing economic infrastructure along the Belt and Road, contribute to a discouraging feedback loop. China’s mercantilist approach, both in its direct relationships with other countries and as articulated in Xi Jinping’s Global Development Initiative, is clearly geared towards replicating China’s securitization of governance and its state-led model of economic development across China’s near abroad. While other regional powers such as Japan, South Korea, and Australia are attempting to push back on this overall trendline—and there are indications that China’s economic weakness may inhibit its ability to project both power and ideology going forward—the sheer mass and momentum of the past decade’s efforts will continue to impede the expansion of freedom in the region.

One powerful force that could potentially counteract Beijing’s authoritarian trend is the persistence and consistency with which the region’s youth population has demonstrated its rejection of authoritarian governance models. From the revolution in Myanmar to the uprising in Hong Kong, and the May 2023 electoral results in Thailand, there has been a clear regional demand from young people for more responsive political systems and more sustainable and equitable growth. This youth wave dovetails with the region’s vulnerability to climate-related challenges, notably in Pacific Island states and littoral nations affected by extreme weather events, and many are calling for a concerted focus on environmental preservation and pragmatic solutions. Beyond the existential threats faced by the most vulnerable states, the general pursuit of cleaner air and water, fewer plastics, lower carbon emissions, and protection of biodiversity, has gained momentum across societies in the region as they progress, modernize, and move up the value chain.

Persistent challenges such as inequality, weak protection of minority and women’s rights, underdeveloped political institutions, endemic corruption, and regression in the rule of law are likely to continue to impede the region’s pursuit of both freedom and prosperity. While China’s influence contributes to these challenges, its success is largely derived from taking advantage of long-standing institutional weaknesses within individual countries. The persistence of weak institutions in developing Asian countries, despite substantial aid from various international donors and entities over a period of decades, deserves greater attention. Internal political instability, highly consequential elections, and ongoing armed conflicts within the region add further pressure, creating an environment of uncertainty and turbulence.

The slow growth of prosperous mature economies like Japan, Australia, and South Korea, coupled with the struggles of middle-income and low-income countries, underscores the need for diversified economic strategies toward this complex region. The persistent downward pressure on political freedom likewise highlights the imperative for stable democracies and allied partners to prioritize reinforcement of effective and pluralistic governing institutions in the region. Acknowledging the time and effort required to build political and economic resilience is crucial, especially in anticipating and effectively managing a potential conflict over Taiwan. The global implications of such a conflict are vast, as are the threats to regional and global stability and prosperity posed by the rogue regime in North Korea.

The more stable Southeast Asian countries continue to struggle with efforts to evade the middle-income trap. Recent trends in supply chain diversification away from China could prove to be an important opportunity for countries like Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam, and Malaysia. This diversification has opened up new prospects for these countries, leading to an increasing focus on value-added production. Notably, countries such as Indonesia are actively striving to enhance their domestic production capabilities and move up the value chain, reducing reliance on the export of raw materials and commodities to China. This shift has garnered interest from affluent countries in the region, including South Korea, Japan, and Australia, which are extending support in critical areas such as critical minerals supply chain capabilities.

Amidst these developments, it is evident that positive economic prospects persist, although the sustained pressure on political freedom remains a concern. As such, stable and prosperous democracies in the region, along with their allied regional and global partners like the United States, Europe, and Canada, must continue their concerted efforts to strengthen institutions within these countries. It is crucial to recognize that progress in this domain may not be immediately visible, but the resilience and robustness of these countries’ institutions when faced with inevitable pressures and shocks—whether of the “black swan” or “grey rhino” variety—will be the ultimate measure of success.

Amb. (ret.) Kelley E. Currie is a nonresident senior fellow for the Atlantic Council’s Freedom and Prosperity Center and Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security. She is also a founding partner of Kilo Alpha Strategies, a boutique geopolitical advisory firm. In addition, she currently serves as a senior adviser to the Krach Institute for Tech Diplomacy at Purdue University and as a member of the board of directors of the National Endowment for Democracy, the board of governors of the East-West Center, and the advisory boards of Spirit of America and the Vandenberg Coalition.

EXPLORE THE DATA

Image: People attend a ceremony to celebrate the new year in Seoul, South Korea, January 1, 2024. REUTERS/Kim Hong-Ji