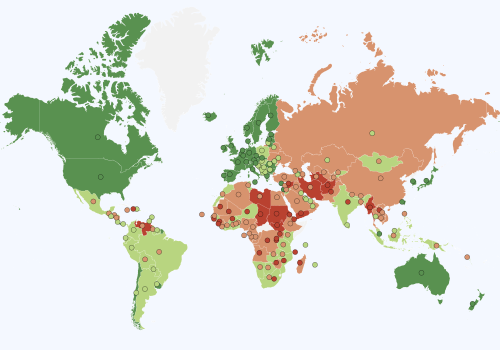

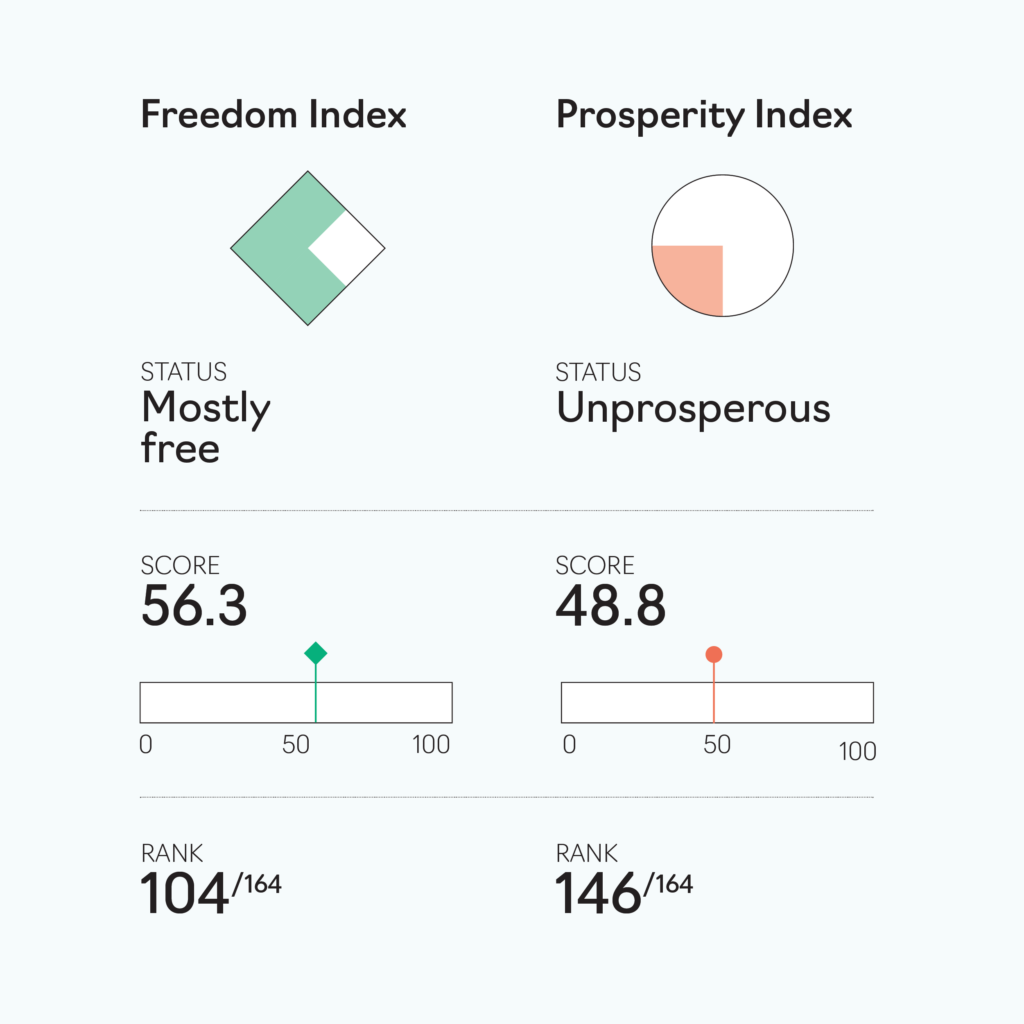

India’s political freedom is at risk

Table of contents

Evolution of freedom

The evolution of political freedom is conceptually the simplest issue in the Indian context. In big-picture terms, the trends shown in the political freedom subindex are very accurate. The graph clearly shows a significant fall in India’s performance in the last ten years. This trend could be termed “democracy capture,” rather than “democracy backsliding,” for a reason that will become apparent below. Looking at the scores on the four indicators of political freedom (elections, political rights, civil rights, and legislative constraints on the executive), India’s score has reduced in every dimension.

Nonetheless, the election score, as reflected in this data, seems to show a steeper fall than most people working in India, or most political scientists, would endorse. And this is the paradox of Indian democracy at this moment. In a narrow interpretation of the electoral core of democracy—which mainly captures elements such as peaceful transitions of power, contestability, and the fairness of the process itself (i.e., Robert Dahl’s polyarchy)—India still does quite well. In fact, no opposition party in India is questioning the legitimacy of elections, which in itself tells you something. Elections are deeply contested, and India performs well on measures of participation, political contestation, or freedom to form political parties. If we look at state or local elections, the degree of contestation is even higher. The dominant Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) rules only 15 of 28 states currently. In the electoral indicator, India may even be performing better than is reflected in the Index. However, there are some concerns over the degradation of some aspects that make elections fair. For example, the BJP receives three times more funding from electoral bonds than all other national parties combined.1 This is a controversial scheme whereby companies can donate to political parties, but the names of the donors are not revealed to the public. Technically only the Reserve Bank of India knows the donors, but there are allegations that the ruling party has this information and uses it to its advantage. The constitutional validity of this scheme is being challenged in the Supreme Court. The Enforcement Directorate, which investigates corruption, typically focuses its efforts more on opposition politicians: about 90 percent of current investigations involve opposition politicians. While this has not yet led to opposition politicians withdrawing from electoral contests, it does seem to place additional burdens on them. But all things considered, the political system does not question the legitimacy of the electoral process.

It is between elections that a decline in civil liberties and political rights for civil society is evident. There is a palpable sense of a decline in freedom in these areas. There is a greater criminalization of dissent. Several political activists, including students, are being held under India’s draconian preventive detention laws. The whole “information order,” (which includes mass media and social media), particularly media in vernacular languages such as Hindi and most television channels, is tightly controlled. There has been a massive decline in academic freedom. It is harder for many groups to obtain permission to protest. The checks and balances of a constitutional democracy are eroding. There is more open dissemination of hate speech that targets minorities.

It is important to underscore the fact that you can have pretty good elections and institutional machinery and yet produce outcomes that are not as protective of our freedoms as we would like. It also points to the fact that the way in which this BJP government regulates or suppresses political rights and civil liberties is somewhat artful. Unlike previous episodes of backsliding in India (e.g., 1975, when a formal state of emergency was declared), there have been no mass arrests or major changes in the law. The government is very selectively targeting particular individuals or institutions, using the formal administrative and legal machinery at its disposal. It uses tax laws, administrative law, and informal threats to target institutions or individuals that dissent from the government. This is artful for three reasons: First, there is plausible deniability. Each of these instances of targeting is presented as simply the normal operation of law, rather than what they are: a form of repression. Second, it allows for a form of statistical reassurance. The numbers of individuals or groups being targeted may not be, as a proportion of the population, very large, and so large sections of society are convinced that these attacks on freedom of expression are not going to really affect them. Third, as a consequence, this selective, exemplary targeting multiplies in effectiveness because it also leads to self-censorship—a more efficient way for the government to achieve its aims. It also makes the issue seem less politically urgent, and divides opposition parties, for whom some targets are more salient than others.

Such strategies are in line with how a lot of modern authoritarianism works. This is a crucial paradox to understand: you can have vigorously contested elections by almost all measurable criteria, and yet that can be accompanied by a dramatic decline in political and civil rights in particular, as well as legislative constraints on the executive. Some might be tempted to say that this makes India closer to an illiberal democracy. This term is an oxymoron though, since some of the basic liberal freedoms—like free expression, equality before the law, freedom of association, and a fair information order—are constitutive of both liberalism and democracy. So an attack on liberal values is, inevitably, an attack on democracy. It also raises the specter of whether those who begin by attacking liberal freedoms may not, at some point, also attack electoral processes. But at the moment one cannot deny the fact that the government of Narendra Modi is popular and that it won power through legitimate means.

What are the drivers of this process? The proximate explanation is simply that Indian democracy is electing to power an explicitly majoritarian government. The BJP’s stated ideology is to make Hindus a self-conscious political force and consolidate Hindu political and cultural power. It seeks to reclaim India as a Hindu nation and rescue it from what it regards as a thousand years of Hindu subjugation in three phases: first subjugation by Islamic rulers, then by the British, and after independence by a secular elite. It also seeks to reclaim a more authentically Indian idiom of discourse and politics. This involves a massive project of cultural engineering: rewriting history, renaming public spaces, marking more sharply the boundaries between the Western and the Indian, or between Muslim and Hindu. It is important to keep this ideological background in mind because a significant explanation for the decline in India’s freedom scores has to do with the domination of this ideology. Wherever you have a project that converts a pluralist society into an ethno-nationalist state, minorities will be targeted. The clampdown on civil liberties is justified in the name of nationalism: almost all dissenters from this ideology are marked as anti-national, which licenses their persecution. The political support for the abridgment of individual rights is mobilized in the name of nationalism.

You can ask a deeper question: Why is it succeeding? The standard story in most democracies that experience this kind of backsliding is that the center and the left, or anybody who is not aligned with the autocratic right, is fragmented, which allows for nationalist political strategies to succeed much more easily. In India today, there is no opposition leader even remotely able to match Narendra Modi in terms of individual charisma. Narendra Modi’s personal biography, as a leader who did not come from either economic or social privilege, allowed sections of marginalized groups to identify with him in a way that would have been impossible a decade ago. Political strategies and political communication do matter, and Modi’s ability to identify with the poor and the lower-middle classes is really quite remarkable. He has been able to construct the argument that most of the opposition represents a kind of corrupt, privileged, ancient regime that for seventy years kept India backward, with low ambitions, and prevented the majority from realizing its full political destiny. We always used to assume that, in India, the natural check on right-wing authoritarianism was the fact that India has lots of cross-cutting divisions (language, region, caste, and so on), which provided a natural distribution of social power. The joke in India used to be that people do not cast their vote, they vote their caste. But if you look at caste voting patterns now, they are much more evenly distributed across parties. One of the interesting things that has happened over the last fifteen or twenty years is that these social groups—that once were assumed to be “natural” checks and balances on Hindu consolidation and majoritarianism—are themselves becoming more strategic in orientation. This is partly a consequence of economic growth and greater political freedom. The dynamics of growth have created inequalities not only among caste groups but also within caste groups. So for example, the interest of different subgroups among the Dalits now diverges, based on their situation in the economy. This has made the relationship between caste and voting a lot more fluid, and has led to a greater individualization of decisions.

Additionally, Mr. Modi, unlike many of his right-wing colleagues across the world (e.g., Erdoğan or Bolsonaro), is actually competent in economic management. We are nowhere near the 10 percent gross domestic product (GDP) growth the government claims, nor in an environmental paradise, nor are we seeing significantly reduced inequality. But the Modi government is a reasonably competent steward of the economy. India still enjoys relative macroeconomic stability, with inflation under control. A growth rate of close to 6 percent provides enough revenue—and political capital—to build a coalition that will support welfare reform.

The legal freedom subindex highlights two important stories. First, on bureaucracy quality and corruption, the massive expansion in state capacity in India in the last fifteen years has produced a movement from retail corruption to wholesale corruption. A lot of ordinary Indians now experience the state as being less corrupt. Previously, a large number of public services would be subject to corruption by bureaucrats. In part, this was allowed to continue because these bureaucrats contributed to systems of political corruption—the bottom-up networks created by political actors. One of the interesting results of economic growth has been that politicians have realized that you can easily make money and extract rents from just two or three sectors of the economy, like construction or defense. And you can now do it in a way that is much less inefficient than used to be the case. It also means that political parties have become more centralized, because now they do not have to rely on diffuse networks of patronage across the system. They can rely instead on particular relationships between state and capital to extract all the rents they want. So, in that sense, the corruption story is relatively good news. But this is accompanied by greater concentration of capital at the top, which may pose long-term challenges for small businesses.

Second, the judicial independence score reflects the real bad news story in the area of legal freedom. The Indian Supreme Court used to be considered one of the most independent supreme courts in the world, particularly over the last twenty years. But it has more or less abdicated its function as a custodian of political values. It has consistently delayed hearings on a range of constitutional cases that would have preserved the checks and balances of the current system. Here are just some of the cases in question: the electoral bond case, which has so far failed to improve the transparency of party donations; a range of federalism petitions relating to the status of Kashmir; and the constitutional validity of the government’s use of “money bills” as a legislative device, allowing it to bypass the upper house, even in nonmoney legislation. The Supreme Court is allowing Hindus to reclaim disputed shrines, the centerpiece of Hindu nationalism. The Supreme Court has more or less subordinated itself to government, going along with the administration’s ideological agenda, even if it puts minority rights at risk. The government’s attack on political freedoms and civil liberties could not happen without the cooperation of the judiciary, and again the way in which they cooperate is very artful. The Supreme Court basically does not hear politically sensitive cases. One example is the situation with a number of students from Jawaharlal Nehru University, imprisoned awaiting trial in connection with the 2020 Delhi riots. The Supreme Court has not heard even the case for bail for three years. The judiciary has improved on things like contracts, contract law, economic disputes, and so on. But on issues where the government’s ideological agenda or power is at stake, the judiciary has, in essence, ceded its authority. The decline in judicial independence is likely to be even more severe in reality than is captured by the indicator.

In terms of economic freedom, it is surprising that the score on the investment freedom indicator is not higher because, at least for domestic businesses, further domestic liberalization is generating a great deal of optimism. Two things might explain the data: First, we are at a juncture where the frameworks for both investment and trade are relatively uncertain. There is an ongoing discussion around the development model that India should follow. The uncertainty around India’s orientation to the global economy makes for domestic regulatory uncertainty. Second (and with more on this below), the current government has been successful in publicly producing some private goods such as roads or sanitation, but it has been unable to enforce other kinds of economic regulations that could sustain economic growth in the long run.

Finally, the overall evolution of the women’s economic freedom indicator is a fair reflection of the real picture, as this is an area that has improved significantly in the last decade in India. However, the drivers of this change are probably not those captured by the Index. The data shown in the figure mainly reflects the legal changes made in terms of working hours flexibility and maternity leave. But these legal reforms apply to a very limited number of firms, and thus cannot explain the significant improvement in women’s economic freedom. Instead, the real improvement in this area seems to come from the increase in access to basic goods such as sanitation, cooking gas, or drinking water, as captured by the progress of India on the Multidimensional Poverty Index. Progress in these areas truly impacts women’s economic freedom and produces a massive expansion of their economic potential.

From freedom to prosperity

India had a remarkable period of growth until 2009, with eight years of almost 8 percent GDP growth. From 2009 to around 2014, the economic situation is hard to assess because India experienced multiple shocks. Dealing with the financial crisis of 2009, the previous government left a remarkably broken financial system. Then the process of de-monetization significantly pulled income growth down. Another remarkable economic reform was the introduction of a single nationwide goods and services tax. In the long run it is likely to be very beneficial, as it raises government revenue more efficiently and cuts down on tax evasion, but in the short run it imposes severe costs on small businesses that are still struggling in some ways. Finally, we had the COVID-19 crisis. Despite all these events, GDP growth has not fallen below 5 percent in the last ten years. This is why there is some optimism about Indian growth.

Nonetheless, there are two noteworthy potential constraints on Indian economic development in the near future. The first is reflected in the recent decrease of the legal freedom subindex, as the tax and regulatory environment is still a lot more uncertain than investors would like. This is not because of a legislative desire to suppress legal freedom in these areas. It is more a function of the state’s inability to create regulatory clarity. The second has to do with the distribution of the growth dividend. The top 20 percent of India’s income distribution has probably done very well lately, as in most countries in the world. The bottom 20 percent has actually not done too badly, because of several welfare measures, as reflected in an improvement in the Multidimensional Poverty Index. It is actually the middle 40 percent that is struggling. India’s workforce is moving away from agriculture at a rate that might be expected. But the transition from low-productivity and low-paid work to high-productivity and better-paid jobs is proving elusive for the middle 40 to 60 percent. There are two reasons for this: First, the Indian economy is still very informal. The government has made attempts to bring more of the economy into the formal sector to increase scale, productivity, and access to credit. But the process of doing it, in the short run at least, raises the costs for very small informal businesses. Many of them are struggling. There is greater concentration of capital. Second, the employment elasticity of capital is rising. It takes more capital investment to create jobs. India’s growth path is still quite capital intensive. The result is high underemployment.

Progress on education is slower than it should be. The improvements in the quality of human capital will take eight to ten years to show up. There is considerable reason for optimism regarding the human capital issue, as it is less of a binding constraint in India than it used to be. The evolution of the health indicator in the Prosperity Index is an accurate reflection of reality, but again, there is a paradox here. One of the big successes of the Modi government has been to make health insurance available to large numbers of Indians. It is one of his flagship schemes and is quite remarkable. But the investment in public health is still clearly insufficient, and this is reflected in the dramatic drop in the indicator due to the COVID-19 crisis. Similarly, Mr. Modi has done very well on sanitation. More people have toilets and fewer Indians practice open defecation. That is a huge success. But in terms of building systems that can transport that sewage and reprocess it, we are not doing so well.

In terms of environmental regulations, there is again an interesting paradox. India is doing better than many peer countries on creation of renewable energy. Progress on solar, wind, and renewables has been remarkable. Yet, the government is at the same time enabling greater investment in coal. Also, the government is still unwilling to enforce some of the key environmental regulations that are already in place. Therefore, India has one of the most polluted environments in the world. All in all, on both environment and health, and despite progress, this government is unsuccessful at creating systems and processes that can account for market failures.

The future ahead

The evolution of political freedom in India is worrisome. In the next two or three years, there is a very high probability that political freedoms will decline even more. The way in which this government has empowered hate speech against minorities and co-opted the judiciary is very concerning.

We are at a big crossroads. It is the first time since 1975 that we must ask this question: Will there be a smooth transition of power? If it looks like this government is struggling and could lose the election, will it accept transition of power as smoothly as India has been used to? And here’s the catch-22: if this government wins, the majoritarian consolidation will be a continued threat to political freedom. But if it looks like it could lose, then the chances of resorting to extra-legal means to either hold on to power or ensure that its successor is not able to function will rise considerably. We can see evidence of this course of action in state elections which the BJP has been losing. In many of them, the BJP is deploying the central government’s power to break up the state governments that have been elected.

On the economic prosperity front, I think there are reasons to be cautiously optimistic. Yet, there is a politically problematic take on the situation: I do not think the harm to political freedoms is going to translate into an economic penalty for India. Large parts of Indian capital and foreign investors may not care. If they can make money, they will come. This has always been the case; it is the blunt truth.

Whether improvements on prosperity will be enough to overcome the structural problem of the middle 40 to 60 percent remains an open question. This group cannot be satiated by welfare expenditure. But nor does it fully participate in the gains of growth. It is also worth remembering that India is a highly diverse federal country. Peninsular states of south India have historically done much better and have per capita incomes 50 percent higher than the rest of the country. North Indian states like Uttar Pradesh and Bihar are still lagging in growth, and that is where most of the poverty is now concentrated. Most of these states present no real challenge to Hindu nationalism as an ideology, but they may resent moves towards greater economic centralization. So India will have to manage the political challenge of a geographically unequal society. This could work for democracy in two opposing ways. On the one hand, federalism can check the centralizing tendencies of Indian democracy. On the other hand, it could exacerbate political conflict and deepen the yearning for authoritarianism.

Pratap Bhanu Mehta is senior fellow and a former president of the Centre for Policy Research, New Delhi and Laurence Rockefeller Visiting Professor for Distinguished Teaching at Princeton University. He was previously vice chancellor of Ashoka University. He is the author of The Burden of Democracy (2003), co-editor of The Oxford Handbook to the Indian Constitution; India’s Public Institutions; and The Oxford Companion to Indian Politics. He was convenor of the Prime Minister of India’s Knowledge Commission (2005–07) and member of India’s National Security Advisory Board. He is also editorial consultant to the Indian Express and a fellow of the British Academy.

EXPLORE THE DATA

Image: Shopkeepers wait for customers at a wholesale electronics market, a day before Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi's government presents its final budget, ahead of the nation's general election, in the old quarters of Delhi, India, January 31, 2024. REUTERS/Sahiba Chawdhary