Russia will suffer decreases in every dimension of prosperity

Table of contents

Evolution of freedom

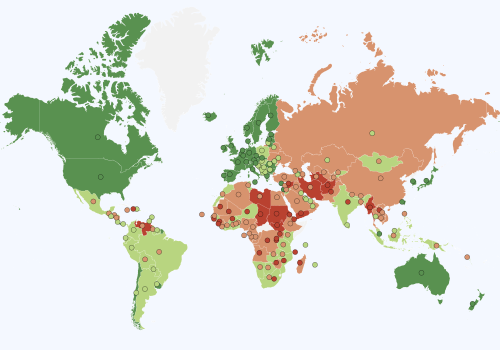

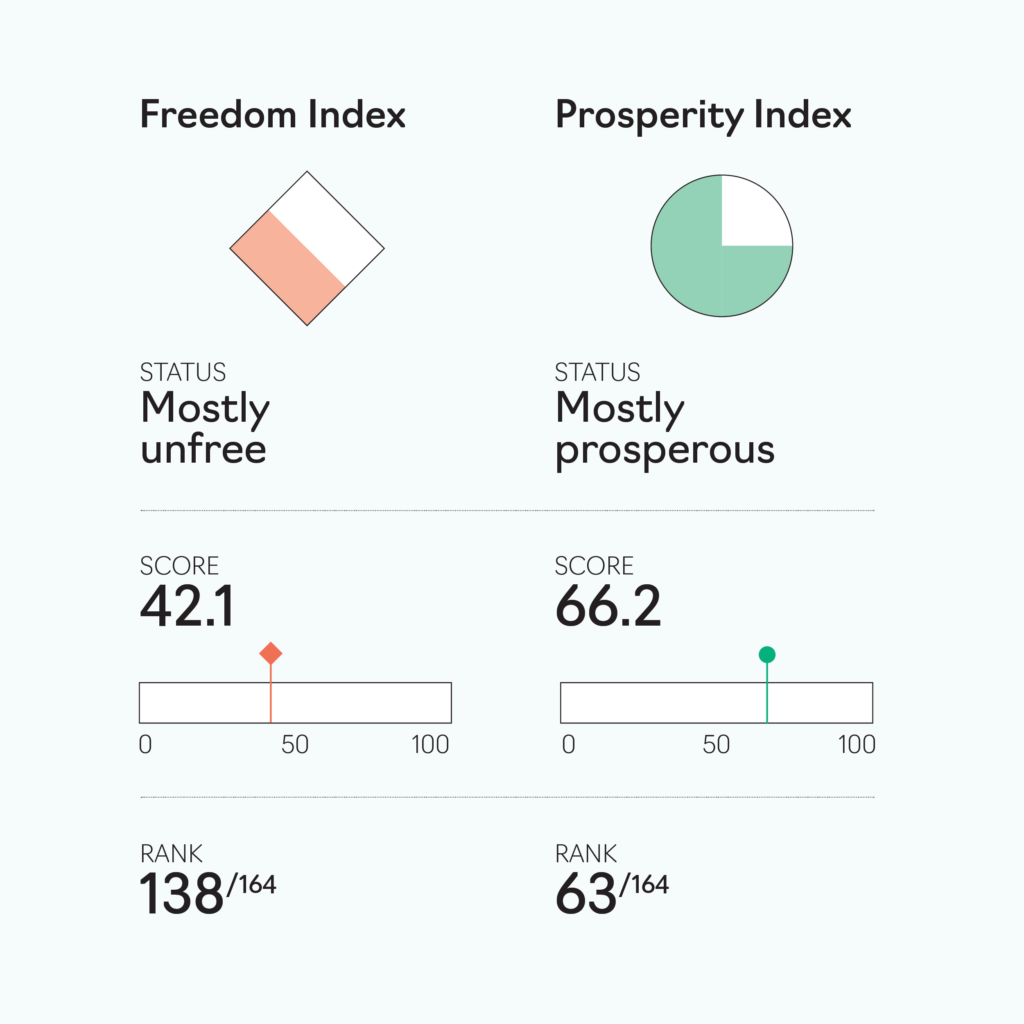

For many years, I have had issues with discussing various graphs and indexes illustrating what is going on in Russia, because the picture on the ground was very different from what those indexes showed. But the Freedom Index very closely represents what I felt was happening in my country over the last ten years: basically, a gradual deterioration of all dimensions of freedoms, but especially political freedom. This process started even before the war in Ukraine, and accelerated after the war started. The deterioration in economic and legal freedoms is not so evident, but this is because the starting points were already low in 1995.

Thirty years ago, Russia was a competitive democracy. Of course, an unstable democracy, as we can see from the way it has unraveled in the twenty-first century, but it was really competitive. Opposition (i.e., those not aligned with the president) controlled the parliament, incumbents would lose elections at the subnational level, and measures of democratic standards would agree that the country could be labeled as a democracy. But the system has gradually deteriorated until today, when there are no longer any competitive elections at any level above small municipalities. Every reasonably sized city or town is already fully controlled from the political center; even in cases where officials are formally elected, they are still appointed.

Civil and political rights are at a minimum. Think of freedom of expression. Nowadays you can get arrested for just mentioning the word “war” when referring to the Russia-Ukraine conflict. I myself am a fugitive of Putin’s “justice,” and by the time this book is published I will probably have been sentenced in absentia to nine years in prison for my social media posts. So, in terms of freedom of the press or individual freedom of expression, Russia today is as close to a perfect score of zero as you can possibly imagine.

The fall into autocracy is also evident in the legal freedom subindex, especially in the components of clarity of the law and judicial independence. A clear example that connects both indicators is the passing of several laws by parliament that clearly contradict the Constitution. The criminalization of any comment on the war that contradicts the story told by the Ministry of Defence obviously contravenes the Constitution, which protects freedom of expression. There cannot be any clarity of the law when day-to-day legislation contradicts the Constitution. And citizens cannot try to defend their rights through the judicial system, as it is completely controlled by the executive.

Economic freedom has never been high in Russia, and the data confirm this. But economic freedom has further deteriorated in the last few years, especially since the beginning of the war. Future updates of the Indexes will surely reflect this evolution, as they will capture the outright expropriation of western-owned property that has been taking place. Foreign companies’ assets have been seized without compensation, and those who were lucky enough to sell their assets have done so at 80 percent discounts and with a 50 percent tax rate imposed. So, trade and investment freedom are surely lower than reflected in the data right now. Even the score on women’s economic freedom is likely to drop in the short run, as Putin’s government propaganda is already pushing the idea that women should marry and bear children at a very young age, because this is good for the nation, and this directly impacts women’s economic rights.

Overall, the picture portrayed by the Freedom Index and its subindexes is consistent with my view of the situation in Russia, and I believe things may be even worse than is currently captured in the data due to lags in the underlying sources.

From freedom to prosperity

The income component of prosperity clearly shows the stagnation of the Russian economy in the last fifteen years. Economic growth was extremely low until 2018, and Russian gross domestic product (GDP) has even contracted in the last few years. Moreover, the Russian economy appears in this graph to perform reasonably well, as it somewhat follows the European trend—but this is misleading. Russia’s income in 1995 was significantly lower than the European average, so the country should have grown faster and caught up with its neighbors, as did Poland and the Baltic countries. This process of convergence is clearly not happening for Russia, and we can even observe a divergence between Russia and the rest of Europe in the last decade.

The inequality indicator is very noisy. There is likely to be significant measurement error at short-term frequencies, but the big-picture situation is clear: Russia was a very unequal country in 1995, and that inequality remains at a similar level. Looking forward, some respectable economists argue that we may see an improvement in the inequality measure. I think there are several forces at play. On the one hand, the government is providing very substantive wartime payments to the families of killed soldiers, and these are disproportionally going to the lower quantiles of the income distribution, which can improve inequality measures. But on the other hand, wartime profits are increasing, and these are captured by the top 1 percent of the distribution. So basically, it is the middle class that is being squeezed. The inequality indicator in the Prosperity Index is the share of income going to the top 20 percent of the distribution, so I think it very likely that this will deteriorate in the coming years as inequality increases.

Regarding minority rights, the worrisome negative trend is obvious in the graph, despite the fact that the indicator only captures religious liberty. The government is now persecuting anyone whose faith is not compatible with the heightened militarism of the Russian state. Even priests of the Orthodox Church, usually in favor with government officials, are being prosecuted if they utter words against the war. Religious minorities whose faith is incompatible with military service, such as Baptists and other minority Christian denominations, face criminal prosecution and extra-legal harassment.

It is not only religious minorities who are persecuted. Think about LGBTQ+ citizens, who are now criminalized to the point where even holding hands in public may see them prosecuted. The current situation is probably worse than in Iran, in some senses. Legally, there have not been any changes in the status of—or official attitude toward—different ethnicities, but it is evident that ethnic minorities in the poorest regions of the country have been disproportionately recruited for the war. Therefore, deaths among minority ethnic groups are significantly higher than, for example, for Muscovites.

The health indicator is one of only a couple in the Freedom and Prosperity Indexes that I do not think paints a fully accurate picture of reality, especially for the past few years. Russia was one of the worst performing countries during the COVID-19 pandemic, with more than a million deaths. The total number is similar to that of the United States, where the population is 2.5 times larger, so Russia performed significantly worse. Also, the indicator is probably not yet showing the thousands of deaths since the start of the war, and the deterioration in terms of mental health for a large share of the population due to post-traumatic stress disorder and the like. In 2023, the birth rate in Russia dropped to the level of the worst years of the economic crisis that resulted in the collapse of the Soviet Union. We will likely see further drops in health indicators in the short run.

In terms of environmental quality, it has always been the case that whatever is good for Russian industry is bad for environmental indicators. And vice versa. For many years Russia was one of the best performing countries with respect to the Kyoto protocol, but this was due to a dramatic drop in industrial output. I forecast further decreases in industrial production, so on that side environmental indicators may improve. But at the same time the government is currently removing several regulations and laws that were passed before the war, so this may have an offsetting effect. The effective ban on any public protest and many civil society organizations, including those working on environmental protection, will further erode the existing protections.

Another important process that is probably not fully captured by the data above concerns the educational system. I refer to the exodus of teachers and professors from all levels of the educational system that have left the country in recent years, and especially since the war in Ukraine began. Many have fled the country, others have relocated, some are looking for a way out. This is a huge blow to the Russian educational system. Moreover, tens of thousands of students who should be increasing their human capital through further education are being mobilized and sent to the battlefield, or have become refugees in neighboring countries due to their fear of being called up to fight. This reality is not yet visible as a fall in years of schooling, but as statistics update it will most likely emerge. Furthermore, this issue is not only about the quantity of schooling as measured by the average years of schooling of Russian pupils, but the quality of the education they receive, which then translates into skills and human capital. If the best professors and teachers are leaving the country, it is clear that the quality of the educational system will suffer significantly.

The future ahead

The short- to medium-term prospects for Russia and Putin’s regime are undeniably going to be determined by the evolution of the Russia-Ukraine war. Putin’s regime entered a declining stage even before the beginning of the war, which is typical of authoritarian and personalistic regimes: following a period of stagnation, the regime reaches its final stage, in which every effort is devoted to maintaining power. Even before 2022, political repression was very substantial. Tens of thousands of people were leaving the country every year because they feared arrest if they said something wrong on social media, for example. Yet the repression has dramatically increased since the war began.

I do not think there is an easy way out of the war, nor from Putin’s authoritarian rule. Change in any personalistic regime is always dramatic and turbulent, and even if a lot of the same people still hold power, it always engenders substantial changes. It was the same with the death of Stalin. I think there is always an upside to this, because if and when Putin is gone, the new leadership will be able to do some things that will immediately improve Russia’s situation. I believe any new leadership would withdraw the Russian troops from the newly occupied territories. Talks about lifting economic sanctions and reopening trade will immediately follow. Some companies that left Russia will quickly return. These steps might not generate sustained economic growth, as the loss of growth potential due to the war is substantial. Nonetheless, they will represent an immediate improvement over the status quo. But for now, until this change in leadership takes place, everything will be defined by the evolution of the war, and, as long as the war continues, Russia will suffer further decreases in every dimension of prosperity.

Konstantin Sonin is John Dewey distinguished service professor at the University of Chicago Harris School of Public Policy. He studies political economics. Previously, Sonin has served as faculty and a vice-president of NES and HSE University in Moscow and guest-lectured in dozens of schools across the country. Now he is on the federal wanted list in Russia for posting information about atrocities committed by the Russian occupying forces in Ukraine.

EXPLORE THE DATA

Image: People walk in the Red Square on a snowy day in Moscow, Russia October 27, 2023. REUTERS/Maxim Shemetov