COVID-19 Recovery in Latin America and the Caribbean: A Partnership Strategy for the Biden Administration

Foreword

From Mexico City to Manaus, the COVID-19 pandemic has ravaged communities throughout Latin America and the Caribbean. In March 2020, families in Guayaquil searched for coffins to bury their loved ones. In April and May, Venezuelans who had fled the Maduro dictatorship were forced to return home after having lost their jobs in neighboring countries. As someone who has spent fifteen years in Congress advocating for the United States to work more closely with our friends in Latin America and the Caribbean, I was deeply saddened as this region became an epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The pandemic’s impact on Latin America and the Caribbean has exposed vulnerabilities particular to the region, such as high levels of informality that made it difficult for governments to manage the disease’s spread, despite both public closures and expanded testing efforts. Weak health systems in many countries led to unequal access to essential health services and disproportionate impact on more vulnerable communities. Stay-at-home orders also exacerbated an epidemic within a pandemic—that of gender-based violence. Calls to domestic violence hotlines skyrocketed and countries like Mexico saw record-breaking femicides in 2020.

Some governments used the pandemic to curtail freedom of expression or take advantage of emergency powers, which accelerated the erosion of democratic norms and institutions already underway in some countries. Economies throughout the region shrunk, with the prospects for a full recovery appearing to be several years, if not a decade, away. A recent United Nations (UN) report concluded that in 2020, an additional 22 million people in the region plunged into poverty. Nearly 60 million people fell out of the middle class. While the population of the region represents less than 9 percent of the world’s population, Latin America and the Caribbean has had over a quarter of the world’s deaths.

Nearly a year later, there are reasons for cautious optimism. Latin America and the Caribbean remains a region of boundless economic potential. Its natural endowments offer unparalleled opportunities to invest in a sustainable recovery. Hemispheric trade and potential nearshoring could stimulate investment, employment, the diversification of economies, and regional integration. The pandemic certainly presents a historic opportunity for the region to embrace a transformative agenda, but a long road ahead remains to repair the damage this pandemic has caused. The United States, as a hemispheric neighbor, has an important role to play in this recovery.

As vaccine deployment begins, we must redouble our efforts to ensure US assistance gets to those who need it most. We need to work closely with our allies to advance an inclusive recovery that reaches historically overlooked groups, including indigenous and Afro-descendant populations.

I will be working with the Biden administration and my colleagues in Congress to ensure US assistance helps address immediate needs such as vaccine procurement and deployment, emergency food insecurity, and poverty. But the administration should also prioritize long-term thinking on assistance to the region that strengthens democratic institutions and health systems, combats corruption, bolsters economies to create more formal jobs, and ends the epidemic of violence against women.

This publication comes at a critical moment to advance our long-term thinking about how the United States can partner with the region in its COVID-19 recovery. It highlights specific short- and long-term actions that can be taken by the United States to help achieve security, accelerate prosperity, and strengthen democracy in Latin America and the Caribbean. The United States has the opportunity to position itself as the most important partner for its neighbors by supporting the region’s sustainable and inclusive recovery. By working with our hemispheric partners during this moment of great need, the United States itself will be stronger, safer, and better positioned to lead this hemisphere into a post-pandemic future.

Representative Albio Sires, (D-NJ)

Chairman

Subcommittee on the Western Hemisphere

Civilian Security, Migration and International Economic Policy

House Foreign Affairs Committee

Table of Contents

II. One Year After the Region’s First COVID-19 Case: Where Are We?

III. Regional Recovery: Why It’s a US Foreign Policy Priority

IV. Goals of a Regional COVID-19 Recovery Strategy: Prosperity, Security, and Democracy

V. A Six-Point Plan to Help the Region Rebuild Stronger

1. Investing in Health: A Key to Regional Prosperity

2. Economic Revitalization: Addressing Corruption and Building Resilience

3. The Future of Hemispheric Commerce: Integration, Infrastructure, and Technology

4. Climate Action: Implementing Commitments and Integrating Policies

5. Education: A Pillar for Growth and Social Inclusion

6. Democracy and Governance: Working Together to Strengthen Institutions

I. Executive Summary

The Americas have been hit harder by the COVID- 19 pandemic than any other region in the world, accounting for nearly half of the 2.6 million global deaths attributed to the disease as of early March 2021. The responses to the pandemic, including ongoing school closures and the shutdown of millions of businesses, have resulted in the largest global recession since the Great Depression. Latin American and Caribbean economies were hit hardest in 2020, with regional GDP contraction (-6.9 percent) more than three percentage points higher than the world average. Regional growth predictions for 2021 will be insufficient to return to the pre-COVID-19 levels of economic activity, lagging behind the rest of the world.

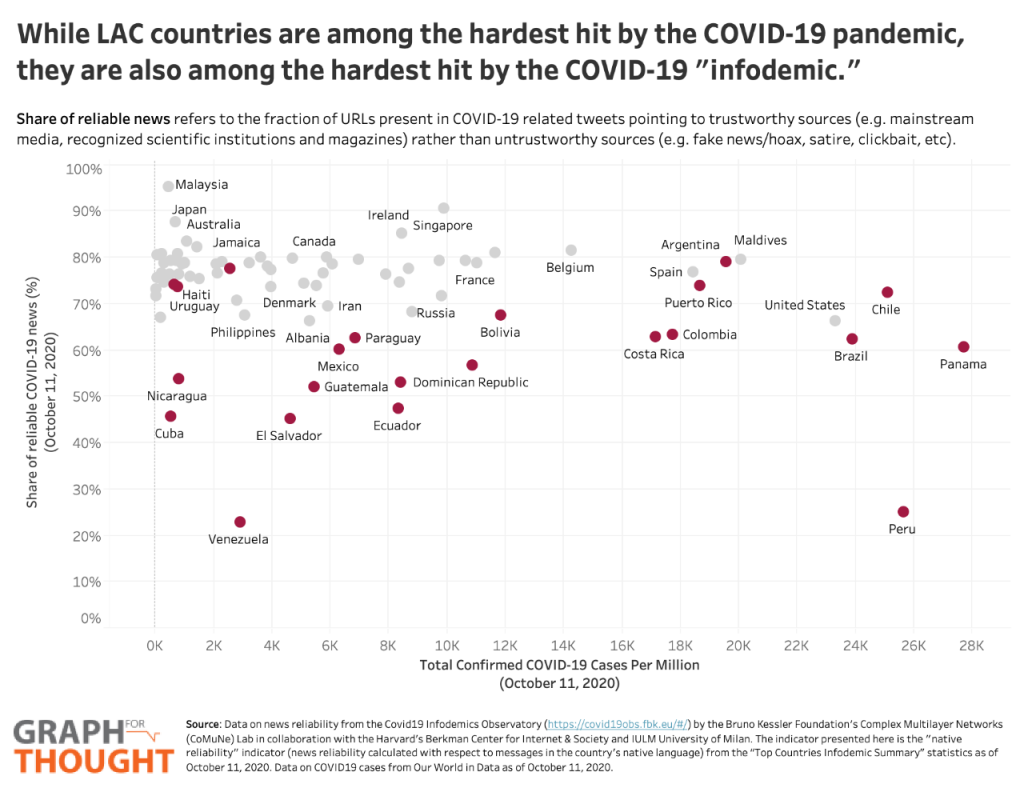

Amid ongoing social and economic disruption, inequality in the world’s most unequal region is on the rise. Millions are falling into poverty, corruption is rampant, and disinformation massively circulated. In the face of the pandemic’s multidimensional impacts, greater international cooperation and public-private partnerships (PPPs) are critical to combat the global crisis. The United Nations, for example, long called for “vaccine multilateralism” to ensure fair and equitable vaccine distribution. By December 2020, more than fifty-seven vaccine candidates were in clinical research, with several front-runners resulting from international collaboration.5 The COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access (COVAX) Facility, established by the World Health Organization (WHO) in collaboration with the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, is another example of a global cooperative effort to end the pandemic. As of the time of writing, twenty countries in the Latin America and the Caribbean region had begun to administer a COVID-19 vaccine.6 While a critical step, vaccination, even if it were to be efficiently administered across the population, will not solve the problems brought on or magnified by the pandemic.

The United States and the Latin American and Caribbean countries can work together to address these issues through a strategy that relies on partnerships and helps to achieve inclusivity and resilience.

A Latin America and the Caribbean region that is secure, economically prosperous, and democratic provides stability and opportunities for the United States in its own hemisphere. This is all the more essential in today’s chaotic and unpredictable world. Thus, it is in the United States’ interest to be the partner of choice for the hemisphere in its COVID-19 recovery.

The question is: How can and should the United States partner with the region? To help Latin American and Caribbean countries—and the rest of the developing world—secure a vaccine, the United States, under US President Joseph R. Biden, Jr., has joined the COVAX Facility, re-entered the WHO, and can further promote PPPs between US companies and countries in the region. In addition to securing equitable vaccine access and distribution, however, Latin American and Caribbean countries face a multitude of issues that have been exacerbated by the pandemic: struggling healthcare systems, lagging supply chain integration, escalating social tensions, rising unemployment, increasing corruption, growing regional nonalignment, a changing climate, and rising public debt alongside weakened corporate and financial sectors. With COVID-19, tourism has plummeted as well. The United States and the Latin American and Caribbean countries can work together to address these issues through a strategy that relies on partnerships and helps to achieve inclusivity and resilience.

US strategic interests depend on a prosperous and democratic hemisphere. Likewise, much of Latin America’s aspirations require a committed and open neighbor to the north. With Biden, the United States will prioritize greater regional cooperation, stronger partnerships, and a return to the principles of multilateralism. This strategy paper outlines the following concrete short and long-term actions, or elements of the strategy, that can be taken by the Biden administration to foster prosperity in the region and ensure that the United States is the partner of choice in the pandemic recovery.

A Six-Point Plan to Help the Region Rebuild Stronger

| STRATEGY ELEMENTS | TOP RECOMMENDATIONS |

6 MONTHS

- Build on rejoining the WHO to increasingly take a leadership position in helping countries secure a vaccine and renew US-WHO scientific collaboration.

- Contribute to countries’ bilateral efforts to secure a vaccine by promoting PPPs between US companies and countries in the region.

- Partner with governments—through the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)—to help strengthen the in-country logistics necessary for expedient, fair, and equitable vaccine distribution.

1 YEAR

- Expand the mandate of the still relatively new US International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) to direct increased investments to countries’ health sectors.

- Increase US Agency for International Development (USAID) assistance in areas such as research and development, disease surveillance, and rapid-response capacity and align its efforts with those of US allies’ development agencies.

6 MONTHS

- Heed and amplify calls from the World Bank for debt sustainability for select Latin American countries amid increased fiscal pressures resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Encourage the reopening of international borders and coordinated testing and quarantine regimes, consistent with international recommendations outlined in the International Civil Aviation Organization’s Council Aviation Recovery Taskforce (CART) report.

1 YEAR

- Expand DFC financing and equity investments by increasing the overall share of financing directed toward the region.

- Provide training and technical assistance regarding the adaptation of country-relevant components of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act and the establishment or improvement of PPP frameworks.

- Expand current anti-corruption efforts by directing new funding toward initiatives to strengthen judicial systems and improve public service regulation and control mechanisms.

- Allow DFC to issue paper in local currency and to finance local currency projects.

- Work closely with the State Department’s Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs to restart student exchange programs that provide a vital source of peer-to-peer learning and understanding, and also facilitate in-country tourism.

- Work with interested national governments to prioritize the expansion of US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) preclearance points to airports in the region that support critical tourism operations, with the Caribbean as a potential starting point.

6 MONTHS

- Harness the financing of the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) and the World Bank to leverage private and public investment in physical and digital infrastructure that reduces transport costs and improves connectivity.

- Work with the IDB and the World Bank to promote public-based loans to countries in exchange for the implementation of institutional reforms to improve the investment climate and spur inclusive growth.

- Extend Section 232 tariff exclusions to more countries in the region.

1 YEAR

- Advance a new, updated twenty-first-century version of the Free Trade Area of the Americas agreement (FTAA) at the Ninth Summit of the Americas, offering a new vision for the future of the Americas.

- Prioritize the updating of the North American Plan for Animal and Pandemic Influenza (NAPAPI), launched by then-US President Barack Obama.

- Extend traveler preclearance to spur business travel to commercial centers across the region.

- Help to convene and structure multicountry regional projects that would be attractive to private sector investment.

- Expand CBP Authorized Economic Operator (AEO) programs across the region.

6 MONTHS

- Work with multilateral banks to reform standards on new credits for development projects, making projects with high carbon impact higher-risk and more costly for countries.

- Strengthen regional collaboration on policies related to food, water, energy, and preparedness for extreme events.

1 YEAR

- With rejoining the Paris Agreement, bring back the Tropical Forest Conservation Act and condition trade agreements on countries’ commitments to meet their Paris climate targets.

- Provide pathways for countries to increase contributions to global funds (i.e., Green Climate Fund), which, in turn, could help expand credit facilities and guarantees for investments on climate-resilience interventions.

- Support governments in the design and implementation of innovative solutions, such as climate smart agriculture, anti-hunger grants, safety net programs for small farm holders, and aid and insurance to farmers, especially in the face of crop failures.

- Provide technical assistance, facilitated by the State Department, to help countries minimize inefficiencies in resource management, such as through water reuse and energy efficiency.

- Provide financial and technical support to subnational entities, particularly to cities, to access capital and resources to address urban communities’ climate resilience in urbanized areas and slums.

6 MONTHS

- Promote a new wave of partnerships between US universities and higher-learning institutions in the region.

- Advance discussions on establishing a regional educational cooperation agreement between the Americas so academic degrees and certificates are mutually recognized across borders.

1 YEAR

- Provide economic incentives to US companies seeking to invest in Latin American and Caribbean education sectors.

- Promote public-private alliances to accelerate the development of digital platforms that enhance teaching and learning processes by applying lessons learned during the pandemic.

6 MONTHS

- Work through the State Department to prioritize anti-corruption trainings that provide technical assistance to help judges, lawyers, and prosecutors both better combat financial crimes, and, in the long run, strengthen countries’ judicial branches.

- Build bipartisan consensus in the US Congress in favor of sustainable long-term assistance to support prosperity and development in the critical Northern Triangle region with clear metrics of success.

- Ensure that Venezuela and Nicaragua sanctions are designed to achieve an ultimate end goal of a restoration of democratic institutions and a return to free and fair elections while not resulting in additional suffering of the Venezuelan and Nicaraguan people.

- Support host country policies to aid Venezuelan migrants living across Latin America and the Caribbean.

1 YEAR

- Provide renewed support to nonpartisan election observation in the region, including through missions organized by the Organization of American States (OAS).

- Prioritize better alignment and greater coordination with European countries and other allies to counter the influence of adversaries in the region.

- Foster a broader and more important role for civil society to help advance government accountability, not only through aid and technical capacity building, but also the political work of recognition and credit of civil society organizations, especially those of traditionally discriminated minorities (i.e., Afro-descendant and indigenous groups).

II. One Year After the Region’s First COVID-19 Case: Where Are We?

Since the COVID-19 outbreak, the Latin America and the Caribbean region has had some of the highest infection and death rates in the world. As of March 9, the region had more than 22.3 million cases and over 700,000 deaths—around a fourth of the world’s total COVID-19 deaths. Despite a slowdown in new case and fatality rates in early October, the region witnessed one of the strongest sustained increases in infections and deaths in the final months of 2020, with Argentina, Colombia, and Mexico each surpassing one million cases between October 20 and November 15. According to the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), recurring waves and outbreaks of COVID-19 will continue to affect the region, pending widespread vaccine deployment.

Nearly thirty countries or territories in the Latin America and the Caribbean region are registered to purchase vaccines from the COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access (COVAX) Facility—an initiative to develop and equally distribute a COVID-19 vaccine led by the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), the World Health Organization (WHO), and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance—and another ten are eligible to receive them as donations. Nevertheless, the COVAX Facility—subject to funding availability—will only guarantee each country enough doses to vaccinate up to 20 percent of their population, driving countries to engage in direct bilateral negotiations with pharmaceutical companies from around the world to secure additional doses and halt corruption in order to utilize limited fiscal resources efficiently.

On December 24, 2020, in a historic feat, Chile, Costa Rica, and Mexico became the first countries in the Latin America and the Caribbean region to begin COVID-19 vaccinations—all administered the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine. Less than two weeks earlier, Mexico became the fourth country in the world and first in the region to approve a COVID-19 vaccine for emergency use. “We have the privilege of being one of the first countries in the world to have access to the vaccine,” said Martha Delgado, undersecretary for multilateral affairs and human rights at Mexico’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. “It is a historic day.” Meanwhile, Argentina’s regulators approved Sputnik V, the COVID-19 vaccine developed by Russia’s Gamaleya Institute, with the first vaccines administered on December 29, putting Argentina in the company of Belarus as the first countries outside Russia to administer the controversial vaccine.

The economic crisis caused by the pandemic in 2020 has only aggravated and laid bare many governments’ structural weaknesses, setting the stage for heightened instability and social unrest in the months and years to come.

Certainly, China and Russia’s presence in the Latin America and the Caribbean region has grown further since the onset of COVID-19. China alone has provided aid in the form of medical supply donations and financial support with a $1 billion loan to be used toward vaccine access. With several vaccine trials taking place in the region, China is poised to be one of the first distributors of the COVID-19 vaccine in the Latin America and the Caribbean region. Russia has taken a similar approach to vaccine diplomacy in an attempt to use the pandemic to assert its global power. Beyond Argentina, trials of the Sputnik-V vaccine are taking place in Brazil and Venezuela, with Russia promising to provide needy countries in the Western Hemisphere with its vaccines once approved.

After years of slow growth and productivity—well below the global average—the GDP for the entire Latin America and the Caribbean region shrank by 6.9 percent in 2020 due to COVID-19, according to the World Bank’s January 2021 forecast. A modest recovery of 4.1 percent is projected for 2021, but risks to the outlook remain tilted to the downside. Unemployment reached 15 percent in 2020 (from 8 percent in 2019), and more than a quarter of the population (up to 27.6 percent) fell into poverty ($5.50 poverty line), compared to 22.5 percent in 2019. As many as thirty-two million people became poor as a result of the crisis. The region will also become more indebted because of the pandemic; it ended 2019 with a debt to GDP ratio of 66.4 percent, which is projected to increase to 74.4 percent by end of 2020.

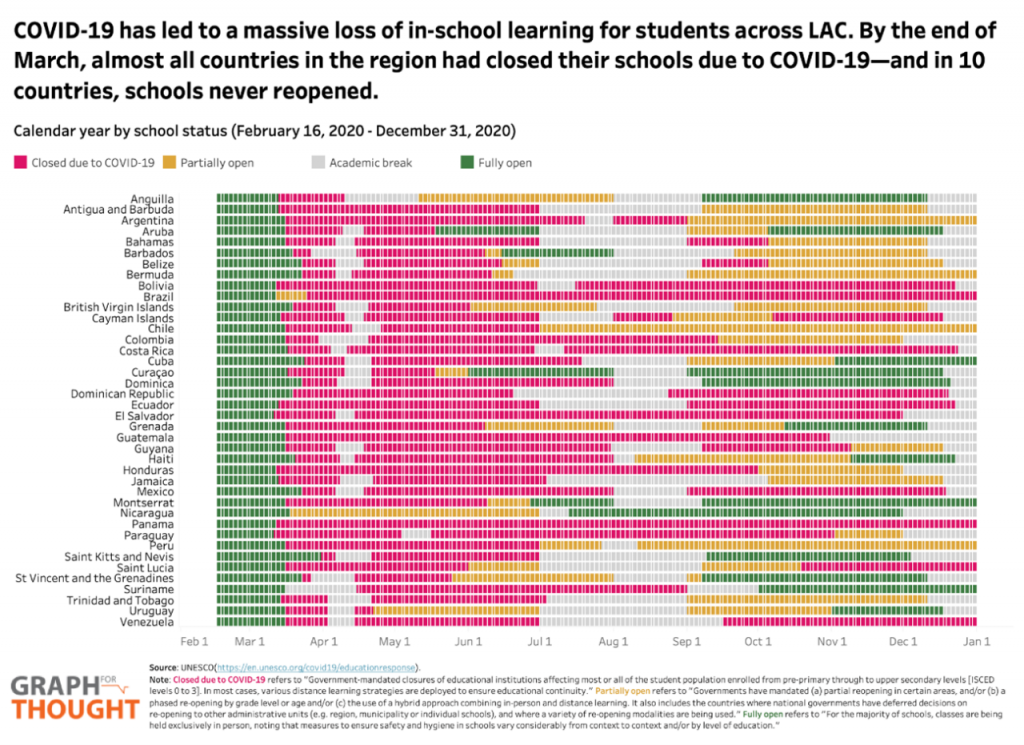

Furthermore, the pandemic has accelerated and worsened the region’s structural and pervasive inequalities; projections in social indicators such as crime rates, school attendance, gender gaps, and inequalities in access to health, connectivity, and basic services are as dire. The emergence of social protests across the region in late 2019 exposed long-repressed sentiments among citizens in a diverse grouping of countries—from Chile and Colombia to Ecuador and Bolivia—with regard to neoliberal economic policies, lack of social protections, and corruption, among other grievances. The economic crisis caused by the pandemic in 2020 has only aggravated and laid bare many governments’ structural weaknesses, setting the stage for heightened instability and social unrest in the months and years to come.

The economic crisis has also dealt a severe shock to Latin America’s labor force of which more than half work in the informal economy. People forced to remain at home, while facing high out-of-pocket healthcare expenses, rising displacement and migration, high income inequality, and a fragile healthcare system, have found themselves at an extreme disadvantage. These inequalities are projected to set back the Latin America and the Caribbean region by at least another decade in its development, with an additional 231 million people estimated to be living in poverty by 2021. The formalization of Latin American and Caribbean economies could benefit female entrepreneurs (who own the majority of small and medium-sized enterprises in the region), broaden tax bases, and eliminate loan sharks.

Authoritarian tendencies have resurfaced in recent years with new threats to the press and deployments of military forces in order to advance personal agendas. With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, some leaders are utilizing postponed elections and government containment measures to their advantage to maximize their grip on power. Corruption continues to be among the top impediments to regional advancement with violent protests and social unrest questioning the underlying fabric of democratic institutions. Certainly, the pandemic has set a new standard for corruption in the region, with reports of high-level government officials, such as those in Panama and Bolivia, purchasing medical supplies at inflated prices. In Brazil, the home of Wilson Witzel, the governor of the state of Rio de Janeiro, was raided by police as part of an investigation—“Corona Jato”—into the embezzlement of $150 million in public funds to build a field hospital.

Despite the gloomy outlook, in some countries stimulus packages have been effective and remittances have increased after an initial decline. Fitch Ratings’ corporate credit indicators forecast an improving economic and operating environment for most of the region in 2021. Brazil is projected to have the region’s shallowest recession from the pandemic. Peru and Chile have also instituted stimulus packages and enjoyed investment-grade credit ratings. Remittances to Latin America totaled nearly $100 billion in 2019. In 2020, while there was a notable decrease in remittances and an overall prediction of a 20 percent decrease in remittances for the region, several countries have bounced back as the US economy recovered: by June, the Dominican Republic had received 26 percent more remittances, Honduras received 15 percent more remittances, and El Salvador received 10 percent more remittances as compared to June 2019.

For its part, as of September 4, 2020, the Trump administration said it was providing $141 million in assistance to help countries in the Latin America and the Caribbean region respond to the pandemic, representing only 9 percent of US global COVID-19 assistance. Amidst this underwhelming US investment in the region, other global players, notably China, have stepped up to support countries in the Latin America and the Caribbean region. China’s $1 billion loan to the region for vaccine access has furthered its status as a vital partner of choice for developing countries facing the pandemic. Russia has similarly targeted developing nations with vaccine trials in exchange for supply deals for its state-produced Sputnik V vaccine. The United States must play a bigger role in the region’s COVID-19 recovery and position itself not just as any partner, but as the most important one for the region.

III. Regional Recovery: Why It’s a US Foreign Policy Priority

Given its geographic proximity and economic, political, and security interests, the United States can and should play an important role in the Latin America and the Caribbean region’s COVID-19 recovery. Long-term interests require that recovery from the multidimensional effects of the pandemic be done with regional countries working alongside the United States to build back economies and institutions stronger and better positioned for the following decades. The United States needs to make up for time lost in 2020 and be at the forefront of partnering with the region in this recovery; seizing this moment will be critical in determining the extent to which the United States, rather than other global powers, builds goodwill and influence at this time of great need.

At the same time, a stronger hemisphere, with a recovery facilitated by and in line with US interests, would shape new opportunities for advancing US economic and security interests while helping to strengthen democracies. If such a role is not seized by the United States it would create a regional vacuum that will be filled by adversaries seeking to steer the region in their realm of interest and influence.

With US leadership and diplomacy a priority for the Biden administration, this is a critical moment to collaborate with regional partners—as peers—to understand their concerns, interests, and vision for long-term recovery. A regionwide strategy would include deepening cooperation with governments, civil society, the private sector, and academia to reinforce the ideals of democracy and lay bare the weaknesses of anti-democratic leaders. But to do so effectively, the United States must lead with these values at home to achieve sustained impact abroad. Post-pandemic recovery will be an opportunity to advance public-private partnerships (PPPs) and US-Latin American private sector cooperation to favorably position the region for long-term, equitable growth and prosperity. Likewise, twenty-first-century transformations in common areas of understanding, such as climate change mitigation, clean energy technology, technological advances, among others will be conducive to hemispheric interests and prosperity.

Under Biden, US foreign policy toward Latin America and the Caribbean promises a return to mutual respect, strong partnerships, and multilateralism. With a renowned vision for a democratic and stable hemisphere and increased US investment toward structural reforms, the United States can help the region embark on a sustainable, resilient, and prosperous trajectory. Biden has constantly expressed a commitment to advancing countries’ economic development and stability as well as to prioritizing human rights and climate action. With a US president who understands and recognizes the region’s importance like few of his predecessors—Biden visited the region sixteen times as vice president, more than any other in US history—Biden is well positioned to work closely and collaboratively with allies and multilateral institutions to alleviate the pandemic’s damage to the region’s health systems, economies, and societies overall. With renewed and strengthened alliances, the United States can join Europe and Japan in together helping Latin America and the Caribbean build back better.

IV. Goals of a Regional COVID-19 Recovery Strategy: Prosperity, Security, and Democracy

It is in the best interests of the United States that the Western Hemisphere is secure, prosperous, and democratic. These longstanding goals—drivers of this strategy paper—are even more imperative today given the chaotic nature of the world order. The global community is undergoing disruption in a multitude of ways, from a worldwide health crisis and its resulting recession to new directions in great-power competition. In shifting back to a policy of mutual respect, partnerships, and collaboration, and with a laser focus on being the partner of choice in the hemisphere’s post-COVID-19 future, the United States will be able to help the hemisphere emerge from the crisis stronger, more secure, and with the region as a stronger ally.

At the broadest level, the goal of the United States should be to: a) facilitate inclusive economic prosperity with free market economies that spur development and are conducive to US economic partnership; b) promote security so that the United States and countries in the region can partner in confronting transnational crime, illicit flows, and threats to the rule of law; and c) revitalize democracy and good governance. The region’s recovery provides a catalytic opportunity to leapfrog development roadblocks and to, therefore, accelerate a more positive trajectory for the Western Hemisphere. US interests lie squarely in a safe and prosperous hemisphere.

As noted above, the COVID-19 crisis is projected to set back Latin America and the Caribbean by at least another decade in its development. The cost of inaction for the United States could be critical, with reverberations in some countries including inequality, instability, migration, corruption, authoritarianism, social unrest, and loss of human capital. These are some of the reasons why the United States should help to provide momentum for Latin America and the Caribbean to build back—in sectors from health to education—and emerge from the crisis on a more strong, sustainable, and prosperous path.

In the long term, the United States should solidify its position as the most important partner and ally for the Latin America and the Caribbean region and continue to enable twenty-first-century transformations in areas such as healthcare, education, and climate action, while addressing longstanding impediments to prosperity, such as corruption, that are not conducive to US economic interests.

In the long term, the United States should solidify its position as the most important partner and ally for the Latin America and the Caribbean region.

In the short term, the United States should be a greater resource and partner at this moment of crisis and direct even more assistance and private sector investment to the region. Renewed relationships should have respect, democracy, and human rights at their forefront. Aid and investment should be directed at areas of mutual interest that also address the root causes of poverty, inequality, and climate vulnerability.

This strategy seeks to achieve the following goals:

Increased Prosperity: Where Latin American and Caribbean economies recover from the pandemic with a new, more prosperous and inclusive economic trajectory; greater investment and stronger fiscal positions generate opportunities for innovation, particularly in health and education, and poverty alleviation; and free markets and interregional cooperation create conducive environments to advance US economic interests.

Improved Security: Where Latin American and Caribbean countries are closer to the United States than to US rivals, countries are capable of confronting a broad range of regional and global challenges, and transnational crime and illicit flows are curtailed.

Strengthened Democracies: Where respect for human rights and democracy is maintained across the region, good governance is revitalized and democratic backsliding is halted, and foreign actors’ efforts to undermine democracy are prevented through strong US partnership.

To achieve these goals, the next section proposes a six-point plan to help the region rebuild stronger.

Challenges

As a global COVID-19 epicenter, several Latin American and Caribbean countries are reeling from some of the highest numbers of absolute and per capita COVID-19 cases and deaths worldwide. Preexisting inequalities in access to healthcare and connectivity have been deepened by the pandemic. Pre-pandemic, the Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO) warned that 30 percent of the population in the Latin America and the Caribbean region (more than 200 million people) did not have access to free healthcare. As of December 2019, public spending on health as a percentage of GDP was estimated at 5 percent on average throughout the region, below the 6 percent minimum recommended by PAHO.

Countries in the region face the COVID-19 pandemic amid a shortage of healthcare resources and capacities, especially in comparison to Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries. Pre-pandemic, only 9.1 intensive care unit (ICU) beds existed per 100,000 people in thirteen Latin American and Caribbean countries, much lower than the OECD average of twelve. COVID-19 is also projected to increase obesity and all forms of childhood malnutrition in the region. Simultaneously, patients with noncommunicable diseases risk being neglected by overwhelmed healthcare systems.

Health systems are under intense pressure to overcome regulatory hurdles, secure the required doses, have the necessary syringes and needles, and put in place a distribution plan that prioritizes the most at-risk people.

In addition, Latin American and Caribbean countries are reliant on extra-regional imports of medical products essential for treating COVID-19, with “less than 4 percent of medical products sourced within the region itself,” as reported by the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. For example, the deployment of COVID-19 vaccines in the Caribbean under the COVAX Facility is expected to get underway in March, but it will only cover 20 percent of the population and few Caribbean island nations have bilateral agreements to deploy vaccines to the remaining 80 percent of their population. Vaccine insecurity in the Caribbean stems from the region’s structural debt—a lack of fiscal space limits options.

Although Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico have each announced plans to domestically produce a COVID-19 vaccine, all three countries are relying on foreign-developed vaccines at first. Foreign or domestic, and even with vaccine deployment underway in some countries, longstanding distribution hurdles will present a logistical challenge throughout the region.

As of the end of 2020, Argentina, Chile, Costa Rica, and Mexico had begun inoculations. Mexico’s five-stage vaccination plan began in December with health workers, followed by Mexicans over the age of sixty. Brazil released a national immunization plan committed to vaccinating fifty-one million Brazilians by June 2021, but lagged behind others in the region in approving a vaccine. With competing vaccines being distributed or in the possible pipeline, health systems are under intense pressure to overcome regulatory hurdles, secure the required doses, have the necessary syringes and needles, and put in place a distribution plan that prioritizes the most at-risk people. Meanwhile, geopolitics is at play with Russia and China seeking to lead in vaccine distribution to emerging economies, thus creating an urgent need for renewed US leadership in the region’s healthcare ecosystem.

Opportunities

In the region’s recovery, increased investment in health ecosystems, including infrastructure, will be vital. Because Latin American and Caribbean governments are facing the pandemic amid a strained fiscal environment, they must work with and protect firms and workers to avoid bankruptcies and unemployment. Multisector collaboration will also help to ensure the production and distribution of essential products, including medical supplies and medication. Amidst fiscal deficits, governments are under pressure to secure private and foreign investment aimed at both health infrastructure and telemedicine.

Growth in telemedicine is a huge opportunity to address the rural-urban healthcare divide. Investing in technology that enables remote healthcare can also make higher quality healthcare more affordable. In addition to addressing the divide between the quality of urban and rural healthcare, telemedicine allows for receiving health services while maintaining social distance, which can help mitigate the spread of COVID-19 and other diseases.

Importing and trading a vaccine will be critically important as most countries in the region are not yet able to locally produce one. The United States can also assist countries in developing distribution plans. While some countries, notably the larger ones—Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Mexico—have released national vaccination plans, the United States could provide technical assistance in distribution and deployment logistics to smaller countries. Lastly, strengthening domestic pharmaceutical capabilities will help to increase countries’ resilience to future crises.

US-produced COVID-19 vaccines show the highest efficacy rates and yet no Latin American country is planning to roll out these vaccines at scale for a majority of their citizens. This can be explained, at least partially, by supply constraints. While pharmaceutical companies from other regions, like AstraZeneca, have secured tech transfers with Latin American manufacturers with the support of their governments, Moderna and Pfizer, both US pharmaceutical companies, continue to rely solely on their own production capacity, which has not significantly expanded. Supporting the expansion of these companies’ vaccine production will contribute to protecting the Americas from COVID-19 while bringing Western Hemisphere nations closer together.

Helping to accelerate twenty-first-century transformations in the region’s healthcare ecosystems is in the best interest of the United States and will also open the door for bilateral and multilateral private sector cooperation and PPPs throughout the hemisphere.

Recommendations

Investing in the region’s health ecosystems and its future pandemic preparedness is vital to the entire hemisphere’s security and prosperity, including that of the United States. Failure to partner with the region’s health systems now will further open the door for greater Chinese and Russian influence.

In terms of access to COVID-19 treatments, the United States can contribute to countries’ multilateral and bilateral efforts to secure a vaccine. On the multilateral front, the Biden administration has already reentered the WHO, but it can go further by helping to strengthen the organization’s capacities. The loss of US funding to the WHO would have been catastrophic if permanent; the United States contributed $893 million to the agency’s 2018-2019 budget and it still owes $60 million in outstanding membership fees. In addition to monetary contributions, by reentering the WHO the United States will promote renewed US-WHO scientific collaboration that is critical to advancing global health. In order to further scientific collaboration and help secure and distribute vaccines to middle and lower-income countries, the United States, under Biden, has joined the COVAX Facility. As mentioned above, several Latin American and Caribbean countries have signed commitment agreements with the COVAX Facility.

On the bilateral front, the United States can contribute to multistakeholder governance as outlined in the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 17, as the COVID-19 crisis can only be faced through strong partnerships and collaboration. US pharmaceutical companies have signed supply agreements with regional governments for their COVID-19 vaccine candidates. Pfizer, for example, has signed agreements with Argentina, Chile, Ecuador, Mexico, and Peru to guarantee millions of doses of its vaccine developed with German biotechnology company BioNTech. In order to galvanize the strong international cooperation needed to recover from the pandemic, the Biden administration can further enable PPPs between US companies and countries in the region.

As mentioned above, countries across the region have begun readying vaccine distribution plans, even before approving vaccines. In the near term, the US Agency for International Development (USAID) should provide support to Latin American countries related to rolling out COVID-19 vaccination plans and responding to COVID-19. USAID has supported Latin American countries for several decades to help contain infectious diseases like AIDS and Zika, among others. COVID-19 is the biggest infectious disease challenge that Latin America faces at the moment, taking more lives than several important chronic diseases in the region, such as cancer or even diabetes.

Technical experts from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) can also assist countries that have not yet developed distribution plans to ensure vaccines are distributed in a fair, ethical, and transparent way. The CDC partners with foreign governments and ministers of health to strengthen public health services and ensure the world is better prepared to face global health threats. From helping to establish a meningitis immunization campaign in Burkina Faso to strengthening pandemic response in the face of the Ebola outbreak in Uganda, the CDC was a great resource to help strengthen in-country logistic sufficiency necessary for fair and equitable vaccine distribution. Lastly, the United States is preparing a comprehensive logistics and data analytic effort where CDC’s V-SAFE program, a new smartphone-based after-vaccination health checker for people who receive COVID-19 vaccines, could be analyzed and replicated in the Latin America and the Caribbean region with USAID’s cooperation.

The Biden administration should take concrete steps to strengthen health ecosystems and create a region more resilient to future crises by, among other things, expanding the mandate of the still relatively new US International Development Finance Corporation (DFC). Currently, DFC partners with the private sector to finance projects across the globe in various sectors, including energy, critical infrastructure, healthcare, and technology. Increased investments should broaden the definition of critical infrastructure (roads, ports, transmission lines, power plants, etc.) to include health infrastructure, disease surveillance systems, emergency operations centers, and countries’ domestic research and development to strengthen domestic preparedness capacities for health emergencies. The US Congress can broaden the DFC’s mandate through the passage of a bill that would succeed the BUILD Act, which received broad bipartisan support and was signed into law in October 2018.

The United States should also strengthen the region’s health systems, future pandemic preparedness, and, consequently, its self-reliance, by increasing USAID assistance in areas such as research and development, disease surveillance, and rapid-response capacity. Increasing assistance in these areas will also help to encourage the transfer of research and development (R&D) from the United States to the region. At this time, the capacity of Latin American and Caribbean countries to promote domestic R&D is, and will continue to be, limited due to the burden of COVID-19 on countries’ health ecosystems. Thus, it remains more important for collaboration to transfer research developed in the United States to the region.

Helping to accelerate twenty-first-century transformations in the region’s healthcare ecosystems is in the best interest of the United States and will also open the door for bilateral and multilateral private sector cooperation and PPPs throughout the hemisphere. USAID assistance can also be better leveraged by aligning it to the region with other development agencies’ efforts, such as those by the United Kingdom’s Foreign, Commonwealth, and Development Office (FCDO). Through increased and allies-based assistance to Latin American and Caribbean countries, and additional resources directed to the abovementioned areas, USAID can further strengthen local capacities and foster stability and prosperity.

Globally, the Biden administration should also help keep the impacts of the pandemic at the top of the agenda by not only resetting US relations with the WHO, but also ensuring the pandemic is the focus of regional cooperation and policy discussions at the Ninth Summit of the Americas to be hosted by the United States and likely held later this year.

Challenges

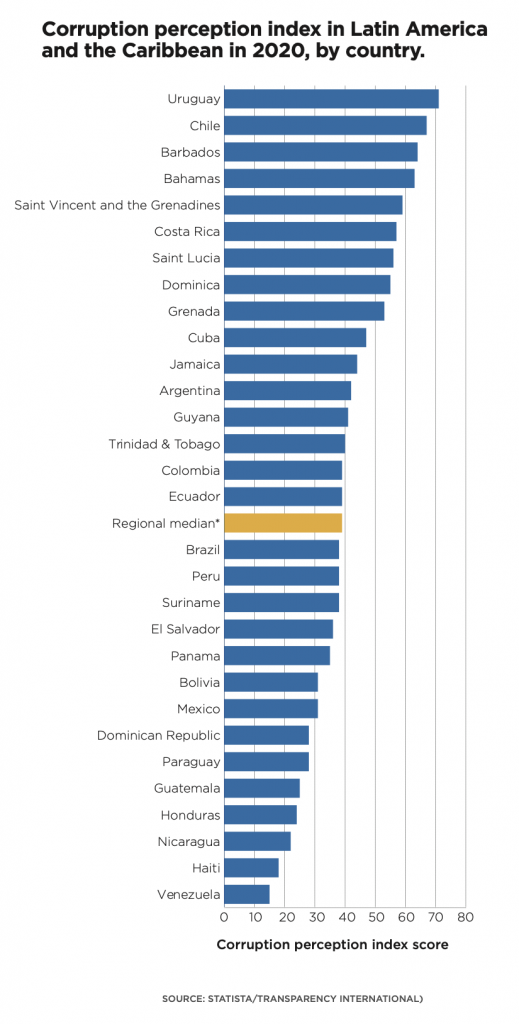

According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), the Latin America and the Caribbean region’s economies are undergoing significant shocks as a result of the slowdown in global demand, particularly among their trade partners (notably China and the United States). COVID-19 has altered the risk appetite of investors and the risk profile of the region as the pandemic accelerates negative trends in rule of law and corruption.

Adequately responding to the COVID-19 pandemic will require 10 percent of the region’s GDP, “including spending measures such as income transfers, credit provision, government guarantees, and tax reductions.” Latin America entered the COVID-19 shock with a significantly weaker fiscal position than in the Global Financial Crisis. While some countries like Brazil, Chile, and Peru implemented relief packages of nearly 6 percent to 9 percent of GDP, others were unable to offer public support. Across the region, central government debt is expected to increase by 9.3 percent to reach 55.3 percent of regional GDP, the highest levels in the last twenty years. This could potentially generate a liquidity crisis and place additional pressure on public accounts, especially as countries work to service these debts. Higher debt-to-GDP ratios could also have negative implications for investment as investors often look at this ratio as an important metric of financial well-being.

Social tensions are also likely to increase as governments enact tax reforms and reduce spending to decrease debt levels. In October, Costa Rican protesters blocked roads and highways in response to a proposed $1.75 billion loan agreement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) which would have led to increased taxes, among other measures.

In 2019, foreign direct investment (FDI) in Latin America increased by 10 percent to $164 billion. However, FDI is expected to have halved in 2020 as a result of the pandemic. Given the challenging global outlook, it is imperative that Latin America address underlying structural issues that have historically stunted investment, including high levels of corruption, bureaucracy, and complex regulatory and tax systems, as well as sectors with dominant players and restricted competition.

The cost of corruption is astounding. In El Salvador, two former presidents—Antonio Saca and Mauricio Funes—were convicted in the past few years of embezzling more than $650 million. Over the course of fifteen years, the Brazilian engineering conglomerate Odebrecht, which changed its name to Novonor in December, paid almost $800 billion in bribes across the region. In Colombia and Peru, for example, corruption is equivalent to almost 10 percent of the national budget; while in Mexico, corruption is estimated to be anywhere from $26 billion to $130 billion. While US foreign assistance to the region amounted to $1.7 billion in FY 2020, excluding additional COVID-19 support, it pales in comparison to the billions of dollars lost to corruption in the region. Corruption remains a driver of poverty, migration, violence, and emboldens inequality. It also serves to erode the legitimacy of governments and institutions.

Anti-corruption initiatives throughout the region faced significant setbacks during 2020, especially in El Salvador, in Honduras and Guatemala where governing authorities ended anti-corruption commissions, and in Peru where Congress blocked anti-corruption reforms led by the presidency. Additionally, COVID-19-related procurement corruption surged across the region. In Bolivia, Health Minister Marcelo Navajas was arrested in May after it was revealed that he entered into a contract to buy ventilators at double the price. In Brazil, a court approved an investigation of Health Minister Eduardo Pazuello’s handling of the COVID-19 crisis and Witzel, the governor of the state of Rio de Janeiro, was suspended from office for his alleged role in a multipronged kickback scheme that included elevated costs for the construction of field hospitals.

Private sector investment is needed now more than ever in the region. That can (and ideally should) happen alongside the DFC, the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), and the World Bank. However, these financial institutions are limited in the amount of support they can provide due to resource and time constraints (with an infrastructure project assessment lasting, on average, nine months), capacity, and the lack of bankability of project structures needed in the region.

Globally, the tourism industry, upon which so many countries are dependent, has been disproportionally impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, with global GDP losses projected at $3.4 trillion. As the pandemic reached the region and an increasing number of countries closed their borders in March 2020, tourism was one of the first and hardest hit sectors. The reverberations were most acutely felt in the Caribbean, where, according to the IDB’s Tourism Dependency Index, five countries—Aruba (#1), Antigua and Barbuda (#4), the Bahamas (#5), St. Lucia (#6), and Dominica (#9)—are among the world’s ten most tourism dependent. Beyond the Caribbean, as the IMF notes, tourism to Mexico, which has been significantly curtailed as a result of the pandemic, represents about 16 percent of both economic output and employment. Closed airspace, travel restrictions, and uncoordinated testing and quarantine protocols have exacerbated the challenges confronting the region’s airlines. By the end of May 2020, the number of flights throughout the region had plummeted by 93 percent, generating an estimated loss of $18 billion, according to the International Air Transport Association (IATA). With tourism worldwide not expected to return to pre-pandemic levels until 2023, building back better throughout the hemisphere will be advanced with a revitalization of the tourism industry.

Opportunities

Although China has provided more than $141 billion in loan commitments to the Latin America and the Caribbean region since 2005, the United States has made promising advances to increase lending to the region, including through the DFC which approved nearly $2.1 billion in funding for the region in 2020, as of September 2020. As part of that, a significant increase in the amount of equity authority provided to the DFC is essential to support projects that are not yet ready for debt, in important sectors such as technology or healthcare. With only $150 million in equity authority in year one, DFC equity is insufficient to put into critical and strategic projects like China does (such as infrastructure) as well as insufficient to meaningfully spread capital around important sectors like tech and healthcare that aren’t at a point to take on loans.

There have also been important initial discussions among US members of Congress to provide a capital increase for the IDB, the largest provider of development funding for the region. The Biden administration should work with Congress to push forward a bill to potentially increase the IDB’s annual lending capacity to $20 billion with guidelines included on the direction and types of projects that would merit US support as part of this new funding. Likewise, the United States should influence the World Bank to ensure that a share of lending to the Latin America and the Caribbean region is protected [$10 billion today, $15 billion if the International Finance Corporation (IFC) is included].

Supporting the region’s economic growth by mobilizing investment and strengthening the rule of law will translate into a more secure and prosperous United States.

To increase private sector investment in the region, the United States can help accelerate the establishment of PPP frameworks and rule-of-law/legal frameworks; it can also promote and facilitate US companies to invest in the region.

Supporting the region’s economic growth by mobilizing investment and strengthening the rule of law will translate into a more secure and prosperous United States. Biden has prioritized tackling corruption as part of his regional agenda, as outlined in “The Biden Plan to Build Security and Prosperity in Partnership with the People of Central America” and in his February 2 executive order on addressing the root causes of migration. With anti-corruption measures comprising a significant component of Biden’s regional plan, countries keen on improving transparency will have support in the White House to overcome domestic barriers. At the same time, the bipartisan US Senate bill introduced by US Sen. Bob Menendez (D-NJ) in the last Congress titled, Advancing Competitiveness, Transparency, and Security in the Americas Act of 2020, exhibits the critical congressional momentum to addressing economic development, the rule of law, and corrupt practices, among other issues. In addition, the United States-Northern Triangle Enhanced Engagement Act (H.R. 2615), passed in December 2020, includes viable recommendations aimed at the US government for cracking down on corruption in the Northern Triangle. It mandates the creation of the “Engel List,” which is based on the broadly useful concept of publicly identifying and taking visas away from corrupt officials.

Post-pandemic, tourism will be a key driver for the Latin America and the Caribbean region’s recovery. Some countries have already begun taking measures to mitigate the economic and social impacts of the pandemic on tourism and prepare the sector for recovery. Several of the region’s iconic export sectors rely heavily on air cargo to access overseas markets, and have suffered disproportionately during the pandemic. Restoring reliable air connectivity will also help drive these iconic export sectors. With telework becoming ever prevalent, Caribbean-island nations could attract “talent” immigration and “telework” tourism in the post-pandemic future. In July, Barbados opened applications for its 12 Month Barbados Welcome Stamp, a “telework” visa allowing people to work remotely in the island country for a maximum of twelve months. With tourism accounting for 12 percent of Barbados’ GDP and 40 percent of its economic activity, the program is a win-win for visitors and the country alike, and offers the opportunity to be replicated across the region. “Our new 12-month Barbados Welcome Stamp is a visa that allows you to relocate and work from one of the world’s most beloved tourism destinations,” Barbadian Prime Minister Mia Mottley said of the program. Antigua and Barbuda followed suit in September with the launch of the Nomad Digital Residence program that allows workers to live there for up to two years. Caribbean island nations and other countries in the region could also benefit from an expansion of the US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) preclearance points.

Recommendations

Greater investment in the region and stronger fiscal positions among Latin American economies are fundamental to generating new opportunities for interregional collaboration and innovation and prosperity.

To address the region’s growing debt burden, the United States should heed and amplify calls from the World Bank for debt restructuring for select Latin American countries amid increased fiscal pressures resulting from the pandemic. Similarly, the United States should also work through international financial institutions to expand lending capacities, especially for countries with historically responsible fiscal and monetary policies, and encourage countries to reprogram debt payments.

The Biden administration can support regional economic recovery by encouraging the reopening of international borders and coordinated testing and quarantine regimes. These practices should be consistent with recommendations outlined in the International Civil Aviation Organization’s Council Aviation Recovery Taskforce (CART) report. By harmonizing cross-border risk mitigation strategies throughout the region, countries will be able to open public health corridors and stimulate the return of air travel.

As the world is experiencing the worst economic dip since the Great Depression, the United States should promote sufficient investments in post-pandemic economic recovery across the Americas. While government investment levels for recovery surpass 20 percent in many countries, a large number of Latin American nations are planning to invest barely 10 percent of GDP in stimulus incentives. A notable example is Mexico, where stimulus plans do not amount to even 3 percent of GDP. Without robust stimulus plans, unemployment and poverty will continue to be on the rise in countries across the region. These conditions are significant drivers of migration to the United States.

To foster increased investment, the Biden administration has an historic opportunity to expand DFC financing and equity investments in the region by increasing the overall share of financing directed toward the region, while, as outlined in the bipartisan Menendez bill, supporting an amendment of the BUILD Act to permit the Caribbean’s twelve countries, excluding Cuba, to access DFC financing. The United States should also provide additional financial support for US businesses operating in the region through the Export-Import Bank and create a custom portal for businesses to identify opportunities for nearshoring through the International Trade Administration.

The United States should also assist the region in the establishment of PPP and legal frameworks, which, in turn, can result in further investment. To establish PPP frameworks, US embassies and agencies can help identify subject matter experts to work with local governments to structure PPPs appropriately. Agencies can bid out the structuring to firms that lead in this space, because they speak the language that investors speak and can develop the right structures. US agencies, development finance institutions (DFIs), and US private firms cannot participate in projects that are not structured appropriately, so several deals are lost to China. By 2015, Latin America became the fastest growing region for Chinese overseas conventional contracted projects. China, in particular, is investing in sectors such as food and agriculture where US firms are absent.

PPP and legal frameworks take years to develop. In the meantime, the Biden administration should consider providing credit support and/or insurance to certain countries to attract private sector investment in a meaningful way. Right now, the DFC provides political risk insurance, but that does not include credit support that would be needed to meaningfully attract investment. The Biden administration should consider providing a full backstop to attract meaningful investment in the region while countries in the region develop all the frameworks.

In addition to credit insurance, true, local currency lending and investment can provide much-needed local capital. While the DFC is authorized to lend in local currencies, its funding mechanisms do not allow it to do so cost effectively. Today, the US Department of the Treasury does not allow the DFC to issue paper in local currency (or the US government to do so on behalf of the DFC). In contrast, the IFC and the IDB are able to issue paper in local currency—clearly more efficient from a cost perspective. As a result, the DFC’s cost can be up to 15 percent higher due to the way the swaps have to be structured, which eliminates swaps from being able to finance local currency projects that have strong merit.

Importantly, the Biden administration will prioritize the rule of law and anti-corruption efforts. Corruption stunts socioeconomic growth, with its toll most acutely felt by those to whom it causes the greatest harm. The Biden administration, working through the State Department and efforts already underway by its Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs and the Bureau of Economic and Business Affairs, can vastly expand current anticorruption efforts by directing new funding toward initiatives to strengthen judicial systems and improve public service regulation and control mechanisms, including improving oversight and audit capabilities. The United States cannot continue to pile on accusations of corruption without beefing up capabilities in the region’s court systems.

The United States also has an opportunity to work with willing partners, as noted in the Menendez bill, to provide training and technical assistance regarding the adaptation of country-relevant components of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. Partner countries could be fast-tracked to receive expedited consideration for additional US financial assistance.

A Biden presidency promises a return to multilateralism, globalization, and working with friends and allies across the globe, which could help restore the international tourism market. Positive reverberations could be felt across the hemisphere; as vice president, Biden promised to cut wait times for tourist visas for Brazilians to facilitate a better exchange of ideas and technology. Hence, bringing the return of tourism between the United States and the region can provide financial, technological, and diplomatic benefits to all parties involved. The State Department, with its Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs as a resource, can also work closely with academic institutions to restart student exchange programs as quickly and as safely as possible. These programs provide a vital source of peer-to-peer learning and understanding, but also facilitate in-country tourism—both in the United States and in the region.

In addition, in the lead up to travel picking up again, the Biden administration should work with interested national governments to prioritize the expansion of CBP preclearance points to airports in the region that support critical tourism operations, with the Caribbean as a potential starting point. In September 2020, CBP announced an expansion of preclearance with airports invited to submit applications for consideration. Expediting preclearance airport designations in the region is also a win for US business given the nearly nine million Latin American and Caribbean travelers who visit the United States annually.

Challenges

The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed the fragility of the modern supply chain. “One likely consequence is that global firms will further diversify their supply chains, instead of heavily relying on China,” according to a study by the World Economic Forum. Manufacturing hubs in the region‚ particularly Mexico, could benefit from that shift. But various issues need to be addressed to unlock the region’s full nearshoring potential, including a lack of private investment, technical capacities, certainty in rule of law, and corruption. A likely cooling of trade tensions between the United States and China may also affect the shift to nearshoring. As commercial ties between the two nations are reestablished, globalization may persist over the nearshoring or reshoring of supply chains.

Better infrastructure (both physical and digital) is critical for the region’s development: for example, the region invests around 3 percent of GDP in infrastructure, compared to 8 percent in East Asia. On the US-Mexico front, a lack of alignment early on in the pandemic on what is an essential business, as well as different stay-at-home orders across the region, have caused deep reverberations in supply chains. For example, Mexico ordered manufacturing plants that supply critical components to businesses considered essential in the United States to close. Better coordination would have prevented such supply chain disruptions.

Opportunities

Now more than ever, the United States has the opportunity to reset and reshape hemispheric trade and investment policy. The United States has free trade agreements with twelve countries in the Latin America and the Caribbean region—more than in any other region of the world. Further harmonization of current FTAs and more attractive regulation and taxation regimes in the region will help entice foreign firms. But rules and regulations need to be more flexible and resilient.

The McKinsey Global Institute has identified $4.5 trillion of potential nearshore opportunities in the next five years. The United States’ second-largest trade partner, Mexico remains a top nearshoring choice for US or US-oriented firms. The US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), which updates several of the provisions of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), will further bolster North American integration and US-Mexico cooperation.

To attract global service investments, the Caribbean will need to invest in Internet infrastructure and broader technological capabilities.

Colombia is, likewise, poised to benefit. “Prior to the pandemic, Colombia’s economy was already oriented toward nearshoring opportunities,” including success in attracting companies that outsource business processes, such as French call center giant Teleperformance and Amazon, which together are looking to hire more than 12,000 employees to support their customer services across Latin America. Despite the pandemic, by the end of 2020, the business process outsourcing (BPO) industry in Colombia had created 25,000 new jobs. However, gaps in Colombia’s manufacturing and technological capabilities remain a challenge. And in the Caribbean, where the BPO sector has become competitive in recent years, nearshoring presents tremendous opportunities to develop investment, stimulate employment, and diversify economies. The Caribbean’s BPO industry grew by 17 percent from 2010 to 2015 and by 2019 its workforce neared one hundred thousand employees. To attract global service investments, the Caribbean will need to invest in Internet infrastructure and broader technological capabilities.

The nature of supply chains is evolving as environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors are increasingly incorporated into the supplier selection process and related scopes of work. This “race to the top” emphasizes how supply chains can complement the Biden administration’s domestic ESG efforts, while favorably positioning US companies relative to other competitors that are not actively addressing these issues.

Recommendations

Disruptions to hemispheric supply chains can produce reverberations in the US economy as well as that of Latin American and Caribbean countries. Now more than ever, it will be critical for the Biden administration to work alongside allies in the region to increase the resilience of supply chains as the region looks to be better prepared for the next shock. A greater focus on integration, infrastructure, and technology will help maximize the region’s ability to compete globally while strengthening economic ties with the United States.

The United States should harness the financing of the IDB and the World Bank to leverage private and public investment in infrastructure to reduce transport costs. Investments should go into relocation, nearshoring, and warehousing, but also into technological capabilities (such as engineering and design centers) to facilitate nearshoring processes. Colombia, for example, faces significant challenges in adopting new technologies and preparing for Industry 4.0 (the Fourth Industrial Revolution), particularly in the adoption of artificial intelligence (AI) for supply chain operations. The IDB, the World Bank, and the DFC can all prioritize investment and better align in areas such as single-window systems, technology for border transactions, and broadened connectivity.

The United States can also work with the IDB and the World Bank to help countries promote reforms in their business environments and FDI frameworks so they are better prepared to receive and host companies that would nearshore. The banks can specifically help by providing public-based loans to countries in exchange for the implementation of reforms that seek to create better investment environments and remove bottlenecks.

Biden has an opportunity to safeguard US interests while avoiding the hostility of the previous Trump administration whose application of tariffs on steel and aluminum imports under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 had a negative financial impact on countries in the region, including the United States’ longstanding ally, Colombia. The only countries excluded from Section 232 tariffs are Australia, Argentina, Brazil, South Korea, the European Union (EU), Canada, and Mexico. Biden should consider extending the exclusion to more countries in the Latin America and the Caribbean region.

Now more than ever, it will be critical for the Biden administration to work alongside allies in the region to increase the resilience of supply chains as the region looks to be better prepared for the next shock.

A new, updated, twenty-first-century version of the Free Trade Area of the Americas agreement (FTAA) could be discussed at the Ninth Summit of the Americas, offering a new vision for the future of the Americas. In the meantime, the United States should focus on strengthening and updating existing commercial agreements to ensure both harmonization as well as verification that the agreements are being fully utilized. Regional and bilateral FTAs must be leveraged to ensure the streamlining of and greater facilitation of the movement of goods, services, and data.

On the US-Mexico border, the Biden administration should prioritize working cooperatively alongside Mexico to “build back better” the future of supply chains and commercial cooperation and integration. Along those lines, Biden can prioritize the updating of the North American Plan for Animal and Pandemic Influenza (NAPAPI), launched by then-US President Barack Obama, then-Mexican President Felipe Calderón, and then-Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper at the North American Leaders’ Summit in April 2012. Greater coordination among North America’s health emergency response capacities will only be possible if NAPAPI is updated to reflect lessons learned and best practices from the COVID-19 pandemic as well as provide clearer guidance regarding coordination in the face of future supply chain shocks.

The extension of preclearance operations, including cargo, to Mexico and other countries in the region, could also further enhance supply chains. Currently, CBP has preclearance points for travelers in six countries, two of which are in the Latin America and the Caribbean region (Aruba and the Bahamas). In September 2020, CBP announced it would invite new airports to apply for preclearance by submitting an application, with negotiations already underway for El Dorado Airport in Bogotá. An extension of traveler preclearance could enhance business travel with important commercial centers across the region. Likewise, US customs offices could have lists of “known shippers” and receive digital cargo documents ahead of time, akin to the US-Mexico Free and Secure Trade Program (FAST). This would not only create much more streamlined regional supply chains, it would also allow for better tracking of illicit shipments of drugs, weapons, contraband, etc.

In terms of cargo, the United States launched eight Unified Cargo Processing (UCP) facilities along the US-Mexico border in 2018 to streamline inspection processes. In March 2020, the US State Department announced the expansion of the UCP facility program along the land border. Further expansion of both UCP operations throughout the land border and preclearance operations throughout the region will allow for greater facilitation of efficient trade and travel. However, much of these gains risk being eroded if Mexico’s new national security law, passed by the Mexican Congress in December 2020, goes into effect. Among other things, that law would limit the ability of US law enforcement to work in Mexico, thus preventing CBP officials from carrying out preclearance duties.

Expanding the number of mutual recognition agreements (MRAs) between CBP and its counterpart customs administrations in the region would offer enhanced security and streamlined clearance for international cargo, as well as send a clear signal of support for private sector actors to increase their efforts. The United States has completed only three such agreements with Latin American and Caribbean partners (Peru, Dominican Republic, Mexico), and has clear scope to expand this effort. Encouraging partners to accelerate implementation of World Trade Organization (WTO) Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA) commitments and/or implement OECD best practices could further magnify the impact.

To promote integration with and attract nearshoring to the Caribbean, the United States can play a major role in convening and helping to structure regional projects that would merit private sector investment, for example, multicountry renewable energy projects. No single country can or would be incentivized to do this alone, and the United States could play a meaningful role in helping to coordinate such a project and attract investment to the Caribbean. Certainly, the Caribbean Sea, which the United States shares not only with several island nations, but also with Central America, Colombia, and southern Mexico, remains a geographic priority for hemispheric economic integration. Maritime trade routes and FTAs have created robust regional supply chains, for example in textiles, between Central America and southern US states like Mississippi and Alabama. More industries in the United States and Latin America could benefit from stronger Caribbean integration.

Challenges

Small island nations in the Caribbean are among the most vulnerable to climate change. Besides the pandemic, Central America has also been devasted by the effects of climate change, as seen by the landfall of two Category 4 hurricanes in November 2020. According to the World Bank, between 150,000 and 2.1 million people in the Latin America and the Caribbean region are pushed to extreme poverty every year due to national disasters.

In terms of migration, the World Bank forecasts as many as seventeen million climate change migrants across the region by 2050. And despite the largest freshwater resources per capita, a third of the region lacks access to drinking water. The Latin America and the Caribbean region’s vulnerable food systems have also been threatened by the pandemic. These disruptions to the food supply chain, together with the impact of climate change on agricultural productivity, are increasing food insecurity throughout the region.

Both climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic are disproportionally affecting vulnerable populations. Furthermore, in the face of COVID-19-strained public finances, countries are finding less incentives for aligning public expenditure and tax systems with climate goals. As millions in the region try to survive the pandemic, less emphasis has been placed on green solutions, posing long-term implications for climate change.

Opportunities

According to the World Bank, Latin America has the cleanest energy matrix in the world and 22 percent of worldwide forest areas, positioning it to be a leader in a robust, green economy. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) forecasts the region could account for 25 percent of global agricultural and fisheries exports by 2028, but, as mentioned, climate change poses significant challenges to agricultural activity.

The Biden administration is clear in its prioritization of climate change, clean energy, and food security, both in the United States and abroad. “Just like we need a unified national response to COVID-19, we need a unified national response to climate change. We need to meet this moment with the urgency it demands,” Biden said in December 2020. The post-pandemic recovery presents an opportunity to expand the type of infrastructure that the United States finances. Investments should focus on more inclusive and sustainable public infrastructure, such as electrical grids and smart buildings. Beyond fiscal policy, it will be imperative for countries to align finance flows with commitments toward lower emissions and climate-resilient policies. Lastly, implementing innovative climate adaptation and mitigation programs should be a key component of rebuilding the region.

Recommendations

Across the region, climate change is depriving the most vulnerable communities of their livelihoods and forcing millions of people to migrate. It is urgent for the United States to partner with countries to ensure recovery from the pandemic enables a transition to a more sustainable relationship between humans and nature. Biden’s $1.7 trillion climate plan aims to transform the United States into a clean energy powerhouse. While the focus is mainly domestic, the plan will create positive externalities internationally, with implications for the Latin America and the Caribbean region through investment and standard-setting and for US leadership in the region.

The United States can work with multilateral banks to reform standards on debt repayment priorities for development projects, making projects with high carbon impact higher-risk and more costly for countries. The Biden administration can help mobilize investments in smart infrastructure, clean energy, and climate research and innovation by offering incentives for US firms that supply low-carbon solutions to Latin American and Caribbean countries.