Trade and financial fragmentation: New challenges to global stability

There is greater uncertainty today about the future of global trade than at any time since the post-World War II trading system was created seven decades ago. This was true before the COVID-19 pandemic froze much of the world economy; the health crisis has added a new layer of uncertainty. We are at a historic inflection point: the global trade regime urgently needs renovation and updating to meet new challenges, yet it is fraying and fragmenting. Technology, geo-economics, and discordant national policies are mutually disruptive forces that are driving change and unprecedented volatility. This is the result of an intersection of several near and long-term trends—most prominently, China’s rapid economic rise—that have highlighted a broad diffusion of global wealth and power from the West to the East and South. This long-term trend is reordering trade and investment patterns, changing the dynamics of globalization. Meanwhile, the political and economic fallout from the 2008 financial crisis and Great Recession has fostered an economic landscape marked by growing populist nationalism, US retreat from free trade to managed trade (e.g., tariffs/quotas), diminished global capital flows, and slower growth. The International Monetary Fund (IMF), which had in January projected global growth of 3.3 percent for 2020, revised its prediction in the wake of the pandemic to, perhaps optimistically, -3 percent. Most dramatically, new waves of technological change and digitization are transforming trade and posing challenges to the global trade system.

Perhaps as much as any single trend, the consequences of the deepening economic clash between the United States and China—the world’s two largest trading powers which together account for some 45 percent of global trade—will be a major factor not only in increasingly decoupled US-China economic ties, but also in reshaping global and regional supply chains, the regional trade architecture, and, not least, the future of the World Trade Organization (WTO). US firms moving production out of China, US bans on technology trade and investment in China, and a bilateral enforcement mechanism will have a disruptive impact on global trade and its governance. A US technology boycott of China will almost certainly accelerate China’s “Made in China 2025” effort to move up the value chain and localize technology supply chains. This would bifurcate trade and investment patterns. Much depends on the duration and eventual outcome of this unprecedented trade and technology war. From its onset seventy years ago in the aftermath of World War II, the global trading system— the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and its successor, the WTO—has been a key driver of economic growth and prosperity. World trade grew almost ninefold, from $2.05 trillion in 1980 to $17.43 trillion by 2017. Global merchandise trade reached $19.67 trillion in 2018. From 2005 to 2017, trade in services grew at 5.4 percent annually, faster than merchandise trade, rising to $13.3 trillion in 2017. The economic damage inflicted by the COVID-19 pandemic, which was still unfolding at the time of writing, has led the WTO to forecast a 13 percent to 32 percent reduction in global trade for 2020. In any case, stagnant middle-class wages and waves of immigrants escaping conflict and chaos in the Middle East helped create a populist backlash in Europe and the United States with regard to free trade, which continues to percolate. China’s unanticipated sixteenfold growth since joining the WTO in 2001 fueled this backlash. China’s rise reflects a broader shift in global production and consumption, and the rise of an increasingly non-Western global middle class estimated at 3.8 billion people—nearly half of the world’s population. This trend is illustrated by the shift in the geography of demand— advanced economies’ exports to developing countries grew from $1.2 trillion in 1995 to $4.2 trillion in 2017.

The full text of the paper is split across the various articles linked below. Readers can browse in any order. To download a PDF version, use the button below.

About the author

Related reading

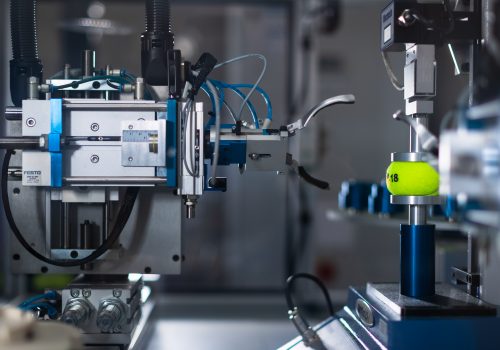

Image: Cover image: chuttersnap, Unsplash