European Union (EU) officials are looking ahead to 2030 as a possible target for enlargement into the Western Balkans. In preparation, the leaders of these six aspirant countries (Kosovo, North Macedonia, Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, and Albania) are gauging how strictly Brussels enforces it directives and regulations—with the energy sector particularly important given its significance to economic growth and social stability, and its impact on the climate. Neighboring Bulgaria provides a test case. Although an EU member now for fifteen years, Bulgaria still relies on coal to generate more than half of its electricity and its energy sector remains dominated by inefficient state-owned entities whose lack of transparency provides fertile ground for Russian meddling. Analogous problems also plague energy sectors across the Western Balkans. The European Commission should therefore set an example for EU aspirants in the Western Balkans by pressing Sofia to live up to its commitments to a competitive and efficient energy sector that advances the energy transition and is independent from Russia.

Western Balkan energy: Too little competition, too much coal, and too much Russia

Energy sectors across the Western Balkans are dominated by state enterprises whose non-transparency and mismanagement have hampered competition, enabled Russian meddling, and slowed investments in the energy transition.

Privatizations of electricity networks in Serbia in the mid-2000s and Montenegro in 2009, for example, were marred by allegations of undervaluing state assets to benefit politically connected investors and thereby defrauding state budgets. The European Commission, meanwhile, recently criticized a lack of transparency in access to North Macedonia’s natural-gas transit infrastructure, as well as the country’s illiquid gas market. And concerns about corruption, mismanagement, and environmental degradation regarding the Kalivac hydropower project in Albania have resulted in major delays and cost overruns, with the project ultimately scaled back significantly.

Russia exploits these energy-sector weaknesses for both economic and geopolitical gain. The 2007 Comprehensive Energy Agreement Between Serbia and the Russian Federation, for example, outsources much of Serbia’s energy security and fiscal control to Russia. Under this framework, Russia’s Gazprom Neft acquired 50 percent of shares in Serbia’s national oil company, Naftna Industrija Srbij (NIS), while Gazprom gained 6.15 percent, yielding a controlling stake of 56.15 percent for Russia’s majority state-owned Gazprom group. Moreover, this arrangement grants Gazprom control over NIS revenue payments to the Serbian government that account for approximately 25 percent of national budgetary revenues.

Serbia is also a key player in the Balkan Stream pipeline, an extension of the TurkStream pipeline that exclusively carries Russian gas under the Black Sea to Turkey, then across Bulgaria to Serbia and Hungary. Moscow has pursued this project, previously called South Stream, since 2007 to resist competition from Azerbaijani gas while bypassing Ukraine as a transit route into Southeast Europe.

Today, Balkan Stream reinforces the efforts of both Serbian President Aleksander Vucic and Hungarian President Viktor Orban to balance relations between the EU and Russia.

Meanwhile, governments across the Western Balkans have also failed to make concerted efforts on perhaps the quickest and most cost-effective way to reduce carbon emissions in their countries’ energy sectors: switching from coal to natural gas as a primary fuel for electricity generation.

Though also a fossil fuel, natural gas emits only one-half to one-third the amount of carbon dioxide when burned that coal does. Moreover, switching to natural gas is a cost-effective way to maintain sufficient electricity volumes to sustain economic growth, even as countries muster the massive investments required to transition fully to renewable energy.

Germany provides an illustrative case. For the past four decades, the German government has been a global leader in transitioning to renewable energy under its Energiewende program, through which it has invested hundreds of billions of euros in wind and solar-power technologies, electricity-grid upgrades, and other elements of the green-energy transition.

Germany chose affordability over sustainability, however, when the US “Shale Revolution” took off in 2008, as new horizontal-drilling and rock-fracturing technologies unlocked vast new quantities of natural gas. This large increase in supply caused the price per unit of energy of natural gas in the United States to drop beneath that of coal. As a result, many US electricity companies switched from coal to gas as a primary fuel. This freed up US coal for export, causing its price per unit of energy in Germany to fall below that of natural gas. Many German electricity producers therefore moved in the opposite direction of their US counterparts, shifting back to “dirty” coal. Germany consequently missed its targets under the 1997 Kyoto Protocol for reducing its greenhouse-gas emissions while the United States, which never ratified the protocol, met its Kyoto targets thanks to its increased use of natural gas rather than coal.

Despite Germany’s short-term reembrace of coal but long-standing pursuit of renewable energy, German industry still chooses to depend significantly on natural gas to cover approximately 27 percent of the country’s fuel demand, second only to oil and significantly more than renewables’ share of 16 percent.

Before its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Russia provided 70 percent of Germany’s natural-gas supply. When Russia subsequently slashed those supplies, Berlin did not double down on renewable energy. It instead replaced Russian gas supplies with liquid natural gas (LNG), largely from the United States, after executing an unprecedentedly quick investment program to develop four import terminals to re-gasify LNG and deliver it into Germany’s pipeline network.

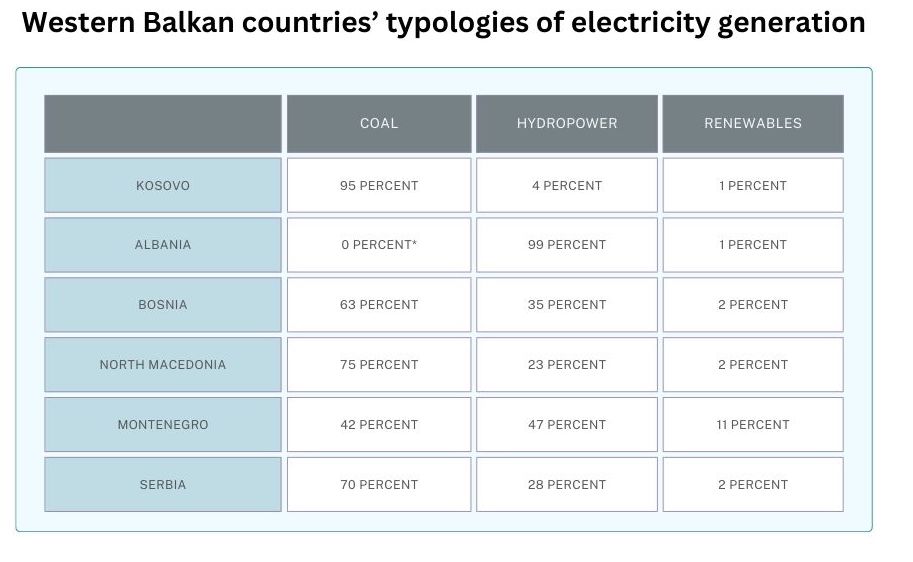

Western Balkan countries, however, have so far not chosen to follow Germany’s lead in relying on natural gas as a key transition fuel to a renewable-energy future. As the table indicates, Kosovo, a potential EU candidate country, uses coal for 95 percent of its power generation—primarily lignite, which is locally plentiful but the dirtiest variety of the dirtiest primary fuel. In North Macedonia, coal is responsible for generating 75 percent of the country’s electricity, while the figure is 70 percent in Serbia and 63 percent in Bosnia.

Montenegro and Albania use less coal and more hydropower. Coal is responsible for 43 percent of electricity generation in Montenegro, hydropower provides 47 percent of its electricity, and wind and solar provide the remaining 11 percent. In Albania, hydropower generates 99 percent of the country’s electricity, but the supply is insufficient, which requires electricity purchases from neighboring countries, most of which are generated from coal.*

Many climate activists are pleased that none of the Western Balkan countries relies on natural gas to generate significant volumes of electricity, and they advocate for the EU to press these aspirant countries to jump directly from coal to renewables. This is precisely what Kosovo plans to do. It is difficult to understand, however, how Kosovo will be able to attract the massive investments necessary to generate sufficient volumes of renewable electricity quickly enough to alleviate serious electricity shortfalls and affordably enough to maintain political stability, especially with 40 percent of its population living below the poverty line.

The government of Serbia, in contrast, is planning to increase the role of natural gas in its economy. Serbia has been buying Russian natural gas for decades. It now plans to increase those purchases via the Balkan Stream pipeline. In addition, Bulgaria and Serbia are finalizing a separate gas interconnection that could theoretically provide non-Russian supplies, but in practice may deliver exclusively Russian gas—albeit disguised as “Turkish gas”—via a recent agreement between the state-owned natural gas monopolies of Turkey and Bulgaria.

At the same time, Belgrade is also planning to diversify its supplies of natural gas to try to reduce its dependence on Russia. Serbia thus hopes to purchase Azerbaijani gas via the EU-supported Southern Corridor.

The Southern Corridor consists of the South Caucasus Gas Pipeline across Azerbaijan and Georgia, which then connects with the Trans-Anatolia Pipeline (TANAP) across Turkey, which in turn feeds into the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline (TAP) across Greece and Albania and under the Adriatic Sea to Italy. The Interconnector Greece-Bulgaria (ICGB) will divert gas from TANAP at the Turkey-Greece border and deliver it into Bulgaria; from there it will soon be able to enter Serbia via a new Bulgaria-Serbia interconnection.

Albania is also weighing whether to introduce natural gas into its economy to expand electricity generation in a more cost-effective way than building new hydropower plants, which have sparked sharp environmentalist protests in the past, such as at the aforementioned Kalivac dam project. Thus, the government of Albania is considering whether to develop localized natural-gas grids in two cities, perhaps as precursors for a national natural-gas grid.

North Macedonia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Montenegro are also considering significant investments in natural-gas infrastructure. Moscow, however, is working to lock these countries and their neighbors into dependence on Russian natural gas, with Russia now developing seven natural gas power plants, in tandem with Chinese financing and technology, in North Macedonia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, and Croatia.

Bulgaria: State monopolies and coal crowd out the private sector and gas

In contrast to plans by five of the six Western Balkan countries to adopt natural gas as a cost-effective way to sustain economic growth and reduce carbon emissions, Bulgaria has been moving in the opposite direction for the past thirty years. Natural-gas consumption has decreased from 7 billion cubic meters (BCM) in 1993 to approximately 3 BCM today. As a result, coal remains the primary fuel for generating 56 percent of Bulgaria’s electricity. In contrast, during the same period, natural-gas consumption increased in Greece from zero to 7 BCM, and in Turkey from 15 BCM to 70 BCM.

To make matters worse, Bulgaria’s electricity system remains so inefficient that 80 percent of the energy released by burning coal in power plants is lost before the electricity reaches customers. This creates a double blow to the EU’s greenhouse-gas reduction targets: excessive use of fuel in general, and over-reliance on the dirtiest fuel, coal.

Bulgaria, like Serbia, consequently consumes more than three times as much energy and emits three times as much carbon per unit of GDP as do the EU’s original member states, which have been consuming significant volumes of natural gas for decades. It is, therefore, no coincidence that the energy intensity of Bulgaria’s economy today is roughly equal to that of Germany and the Netherlands in the 1970s, when they first began to adopt natural gas. Rather than emulating the Netherlands and Germany in switching from coal to natural gas, however, the Bulgarian government continues to subsidize coal-fired electricity, perpetuating decades of non-transparent revenue streams acquired and distributed via state-owned energy monopolies.

Moreover, with the lowest per-capita GDP in the EU, Bulgaria’s energy investments must be affordable, which rules out the enormous capital investments required for a direct jump from coal to renewables. The most cost-effective—and therefore politically sustainable—way for Bulgaria to slash carbon emissions would be to encourage private investment in a shift from coal-fired electricity to natural gas.

Unfortunately, this is not happening. Instead, Bulgaria’s state-owned energy monopoly, Bulgaria Energy Holdings (BEH)—which includes natural-gas supplier Bulgargaz and transmission-system operator Bulgartransgaz—has been crowding out private companies that are eager to invest in Bulgaria’s natural-gas infrastructure.

In 2012, for example, BEH prevented private companies from using Bulgaria’s natural-gas transmission pipelines. The European Commission fined BEH 77 million euros for this anticompetitive behavior. BEH continues to fight that fine in court, while private companies struggle to carve out space to compete with the state monopoly.

Punished for doing the right thing

Bulgaria’s private natural-gas suppliers are under severe financial strain after obeying EU regulations to fill Bulgaria’s underground gas storage (UGS) to 80 percent capacity by November 2022 to ensure security of supply in case Russia cut off gas to the EU following its invasion of Ukraine. This required Bulgarian gas suppliers to buy natural gas last summer at all-time peak prices and inject it into Bulgaria’s natural-gas storage facility at Chiren. Once the winter heating season concluded, natural gas prices in Europe fell to a fraction of the price suppliers paid to fill Bulgaria’s UGS. Normally, Bulgaria’s gas suppliers would have purchased hedges to protect against such dramatic seasonal price shifts. In this instance, however, there appeared to be no reason to do so because the European Commission had directed member-state governments with gas in storage to take “all necessary measures” to protect gas suppliers against such financial losses, as per Regulation (EU) 2022/1032.

Unfortunately, as of February 2024, the Bulgarian government had not yet promulgated the compensation mechanism it promised in accordance with the EU regulation. Private buyers of the stored gas therefore face a brutal financial dilemma: either sell now at enormous losses or hang onto the gas until prices rise, denying them the revenues required to service their loans. Either way, private Bulgarian gas suppliers face a severe liquidity squeeze, which could bankrupt them. As a result, they would likely be unwilling and/or unable to make emergency gas purchases again for this coming winter in case of another supply crisis.

Sofia did, however, extend a highly concessional 400-million-euro loan to Bulgargaz to compensate for some of its unhedged losses. However, the government then rejected requests by the country’s private gas suppliers for an analogous loan. The government’s loan to Bulgargaz would therefore appear to be an example of illegal state aid and another example of the state crowding out private companies in Bulgaria’s energy sector. The European Commission, however, decided to permit the market-distorting example of state aid because of what it terms an “energy” crisis caused by Russia’s sharp curtailment of natural gas deliveries into the EU.

Bulgaria’s nexus among corrupt energy officials and Russia

BEH’s non-transparent and anti-competitive behavior also undercuts the EU’s geopolitical goal of reducing energy revenues on which Russia relies to finance its war against Ukraine.

Bulgaria is infamous for murky ties between its government officials and their Russian counterparts. One former Bulgarian minister of energy, Rumen Ovcharov, is sanctioned under the US Global Magnitsky Act for participating in corrupt deals with Russian natural-gas and nuclear-fuel suppliers, as are Aleksandar Nikolov and Ivan Genov, two former chief executive officers (CEOs) of Bulgaria’s Kozloduy nuclear-power plant.

Today, Russia’s enduring presence in Bulgaria’s energy sector is evident at the country’s most valuable industrial asset, the Neftochim oil refinery in Burgas, which is owned by Russia’s Lukoil. While Bulgaria’s current government may be planning to nationalize and then privatize the refinery via non-Russian investors, its predecessor caretaker government secured a derogation from the EU’s ban of Russian oil imports to feed the refinery until 2027.

Meanwhile, Russia’s role in Bulgaria’s natural-gas sector appears to be growing, thanks to a January 2023 confidential agreement between the state-owned natural-gas monopolies of Bulgaria and Turkey. That agreement, the terms of which were leaked to Bulgarian media and subsequently confirmed by the current Bulgarian government, define a thirteen-year contract that reserves the entire capacity of the gas interconnection between Turkey and Bulgaria for BOTAS and Bulgargaz, locking out all competitors. Moreover, the agreement obligates Bulgargaz to accept any gas from BOTAS without BOTAS having to disclose the origin of that gas, while obligating Bulgartransgaz to deliver that gas to any exit point from Bulgaria via the country’s transmission pipeline system.

These unusual contractual obligations by Bulgargaz and Bulgartransgaz are now reportedly under investigation by the European Commission as potential violations of EU competition rules. The commission is also exploring whether the contract provides a potential “backdoor” for Russian gas to enter the EU even after the EU’s 2027 cutoff date for ending all imports of gas and oil from Russia, a suspicion reinforced by Russian President Vladimir Putin’s proposal to establish what he termed “a Turkish hub for Russian natural gas” during his September 4 meeting with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. Erdogan, in contrast, is pressing for a genuine natural-gas trading hub in Turkey, where supplies converge from multiple directions and prices are set by market forces.

Conclusion: Set the right example in Bulgaria for the EU’s enduring integrity

Analogous versions of these Bulgarian energy problems are prevalent across the Western Balkans. They are almost certain to persist as long as government-owned companies dominate these countries’ energy sectors. Although it will take years to eliminate these state-led market distortions, there are significant steps the European Commission can take now in Bulgaria to strengthen private-sector competition, reduce greenhouse-gas emissions, mitigate corruption, and thwart Russian meddling, thereby setting examples for the EU aspirants in the Western Balkans. The European Commission should therefore press the Bulgarian government to:

- Encourage the Bulgarian government to end subsidies for coal-fired electricity and instead support increased use of natural gas as a transition fuel to renewable energy, while also creating an operating environment that is conducive to investments in natural gas infrastructure by non-Russian and non-Chinese parties;

- penalize the Bulgarian government for illegal state aid that crowds out the private sector and reduces competition, such as the 400-million-euro loan to Bulgargaz;

- enforce Regulation (EU) 2022/1032 by insisting that the Bulgarian government finalizes and implements its “necessary measure” to protect against significant financial losses incurred by suppliers that injected gas into storage ahead of the 2022–2023 winter heating season, as required by the European Commission;

- and demand the same level of transparency regarding the origins of natural gas at entry points into the EU (such as at the Turkey-Bulgaria border) as the European Commission already requires inside the EU at interconnections between member states.

Taken together, these measures would set a powerful example for political and business leaders across the Western Balkans and stress that they must take seriously the EU’s rules pursuing more transparent, efficient, and competitive energy sectors within its member states, which are are driven by well-governed private companies that invest in the energy transition and are free from Russian influence. Absent such steps in Bulgaria, however, Brussels risks signaling to leaders across the Western Balkans that the reform commitments they make today to secure EU membership can be ignored tomorrow. Such disregard for EU requirements risks undermining the credibility, and eventually even the viability, of the European Union as the world’s premier rules-based organization.

Matthew Bryza was a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Global Energy Center and the Atlantic Council IN TURKEY. Bryza was formerly the US Ambassador to Azerbaijan. Follow him on X (formerly known as Twitter) @BryzaMatthew.

The Atlantic Council in Turkey aims to promote and strengthen transatlantic engagement with the region by providing a high-level forum and pursuing programming to address the most important issues on energy, economics, security, and defense.

The Europe Center promotes leadership, strategies and analysis to ensure a strong, ambitious and forward-looking transatlantic relationship.

Further reading

Wed, Dec 20, 2023

Up for grabs? The Western Balkans’ aging energy systems place it between East and West

Issue Brief By

The Western Balkans' hydropower can help Europe's pursuit of energy security. Failure to act on this potential brings significant costs.

Mon, Dec 11, 2023

Getting back on track: Unlocking Kosovo’s Euro-Atlantic and development perspective

Report By

Report exploring the path forward for Kosovo’s integration into transatlantic institutions and the geopolitical and economic challenges and opportunities facing the country.

Thu, Sep 28, 2023

Western Balkans ‘nearshoring’ can turn the region into a strategic asset for the EU

New Atlanticist By Valbona Zeneli

Focused attention is needed to advance an EU-driven economic growth plan and to accelerate the region’s EU accession.

Image: Photo by Matthew Henry on Unsplash