A Global South with Chinese characteristics

Table of contents

- Introduction

- Training future authoritarians

- Party governance as the root of all success

- Global implications and recommendations

- Dataset of Chinese government files

Introduction

At the peak of China’s economic growth toward the end of the 2010s, Beijing began to advocate for an alternative model of governance that prioritizes economic development and rejects the centrality of the protection of individual rights and “Western” democratic processes. At the heart of this new push to legitimize authoritarian governance was the example of China’s own remarkably rapid economic development under Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leadership and an implicit assertion that such successful growth legitimizes not only China’s own autocratic system, but also other non-democratic political systems. The global implications of this development have grown clearer as Beijing has embarked on a steadily expanding mission to promote its political system alongside its economic success in countries across the Global South.

As early as 1985, Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping explained, in plain language, that the Chinese political system would resist changes despite economic integration with the world. He told the Tanzanian president at the time, “Our reform is an experiment not only in China but also internationally, and we believe it will be successful. If we are successful, it can provide some experience for developing countries.”1Deng Xiaoping, “Two Evaluations of China’s Reforms, Originally Published on August 21, 1985,” Qiushi Magazine, July 31, 2019, http://www.qstheory.cn/books/2019-07/31/c_1119485398_45.htm. In 2017, a new Chinese leader, Xi Jinping, repeated this sentiment using similar language.

The path, the theory, the system, and the culture of socialism with Chinese characteristics have kept developing, blazing a new trail for other developing countries to achieve modernization. It offers a new option for other countries and nations who want to speed up their development while preserving their independence; and it offers Chinese wisdom and a Chinese approach to solving the problems facing mankind.”

Source: “Full Text of Xi Jinping’s Report at 19th CPC National Congress,” Xinhua, November 4, 2017, https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/19thcpcnationalcongress/2017-11/04/content_34115212.htm.

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) has long pursued foreign acceptance of Chinese political narratives and encouraged their adoption to further China’s interests.2For example, see China’s promotion of the notion of the “Asian way” or the Belt and Road Initiative, China’s signature global infrastructure initiative. The “Asian way” is a narrative Beijing has used since the early 2010s in its communication with Southeast Asian countries over territorial disputes. Beijing created this approach, one supposedly resting on “Asian values” of “consultation,” “consensus,” “inclusive,” “peace,” “harmony,” and “equality,” to rival discourses that call for strict accordance with international law. For more, see: Hoang Thi Ha, “Building peace in Asia: It’s not the “Asian Way,”” FULCRUM, July 29, 2022, https://fulcrum.sg/building-peace-in-asia-its-not-the-asian-way/. However, China typically does not need to cajole countries into accepting its messaging about successful development. Many developing country leaders, having witnessed the Chinese “economic miracle” in which it developed at a remarkable pace after first opening its economy to the world in the late 1970s, take seriously China’s narrative about the benefits of a more authoritarian system and are willing to consider the calculated risk of experimenting with what Beijing is offering. Even as China’s economic growth has slowed significantly and its political system has grown more repressive under Xi, the number of countries welcoming Chinese governance lessons continues to grow, enhancing Beijing’s global influence. This has significant implications for the future of democracy, the protection of individual rights, and the nature of the global order.

Training future authoritarians

One of the most direct ways that Beijing promotes authoritarian governance is through training programs for foreign government officials on Chinese governance practices. This report investigates a new dataset of Chinese government files on such trainings, uncovering how Beijing uses these sessions to directly promote ideas and practices that marry economics and politics to make a case for its authoritarian capitalism model. Beyond encouraging sympathy for Chinese narratives among officials across the Global South, the programs also provide practical assistance for host countries to fast-track adaptation of Chinese practices. The sessions also appear to serve intelligence-collection purposes by requiring each participant to submit reports detailing their prior exchanges and engagements with other foreign countries on specific training subjects. This report outlines the content Beijing teaches officials in various developing countries and the anticipated benefits to Beijing from these programs. It also explains how these initiatives fit into China’s broader ambitions to undermine the liberal democratic norms that currently underpin the global order.

The author obtained 1,691 files from the Chinese Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) containing descriptions of 795 governmental training programs delivered (presumably online) in 2021 and 2022 during the pandemic. Each program description contains a title indicating the subject of training; the name of the Chinese entity subcontracted to deliver the training; the timing and language of instruction; invited countries and regions; group size; the professional background and demographic requirements for trainees; and training program objectives. Additionally, each description included an outline of the training content, including names of instructors and contact information for subcontracted entities.

In 1981, Beijing began delivering training programs, first branded as foreign assistance, in coordination with the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) as part of an effort to provide aid and basic skills to developing countries.3“China’s External Assistance,” State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, April 21, 2011, http://www.scio.gov.cn/ztk/xwfb/31/8/Document/899558/899558_3.htm. In 1998, the Chinese government broke away from that cooperation arrangement and began offering its own centrally planned training programs directly to governmental officials from countries across the Global South. Beijing reportedly hosted 120,000 trainees from the Global South between 1981 and 2009, with 4,000 programs across twenty fixed areas. With initial success, the programs expanded from their original objective and the number of trainees increased in the next decade, with 49,148 trainees in 1,951 programs between 2010 and 2012, and more than 200,000 trainees in around 7,000 programs between 2013 and 2018.4“China’s External Assistance (2014),” State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, July 10, 2014, https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2014-07/10/content_2715467.htm; “New Era of China’s International Development Cooperation,” State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, January 10, 2021, https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2021-01/10/content_5578617.htm.

Evidence in the newly obtained 2021 and 2022 files indicates that the objectives of Chinese governmental training programs for foreign officials have changed significantly. Trainings are no longer foreign assistance programs with primarily humanitarian assistance aims, but clearly serve to directly inject narratives that marry authoritarian governance with economic development—in other words, to promote an autocratic approach to governance.

According to a cross reference of public releases, the current protocol of governmental training programs involves receiving foreign officials sent to mainland China in accordance with bilateral agreements.5Bilateral agreements include one in 2011 with Indonesia on disaster risk management, one in 2012 with the United Arab Emirates on law enforcement, and one in 2014 with Brazil on space technologies. “Joint Communique between the Government of the People’s Republic of China and the Government of the Republic of Indonesia on Further Strengthening Strategic Partnership,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, April 29, 2011, https://www.mfa.gov.cn/web/zyxw/201104/t20110430_313055.shtml; “Joint Statement between the People’s Republic of China and the United Arab Emirates on the Establishment of Strategic Partnership,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, January 18, 2012, https://www.mfa.gov.cn/web/gjhdq_676201/gj_676203/yz_676205/1206_676234/1207_676246/201201/t20120118_7968517.shtml; “Joint Statement between China and Brazil on Further Deepening the China-Brazil Comprehensive Strategic Partnership,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, July 18, 2014, https://www.mfa.gov.cn/web/ziliao_674904/1179_674909/201407/t20140718_9868425.shtml. These training programs focus on specific areas, and are centrally planned by the Chinese government with designated regional quotas.6For example, 1,000 spaces were granted to officials from Latin America between 2014–2019; two thousand were granted to foreign government officials within the Shanghai Cooperation Organization between 2015–2017. “Xi Jinping Attended the China-Latin American and Caribbean Leaders’ Meeting and Delivered a Keynote Speech,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, July 18, 2014, https://www.mfa.gov.cn/web/wjb_673085/zzjg_673183/ldmzs_673663/dqzz_673667/zglgtlt_685863/xgxw_685869/201407/t20140718_10411920.shtml; “Xi Jinping’s Speech at the 14th Meeting of the Council of Heads of State of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, September 12, 2014, https://www.mfa.gov.cn/web/gjhdq_676201/gjhdqzz_681964/sgwyh_682446/zyjh_682456/201409/t20140912_9384686.shtml. A review of these ”specific areas“ also shows that these programs differ from trainings on humanitarian aid, foreign assistance, and basic skills that Beijing delivered in cooperation with UNDP in the 1980s and 1990s. Rather, the trainings offer authoritarian principles in areas such as law enforcement, journalism, legal issues, space technologies, and many other topics. Given that in China, law enforcement is designed to protect the state and the Party rather than the people, journalism is prescribed to create national unity rather than act as a check against the system, and the law is intended to protect the regime rather than its citizenry, these training programs naturally offer foreign officials different lessons than they would receive from democratic countries.

According to the files obtained, the Chinese embassy in a country identified for training typically is notified roughly three months before a training program is expected to be hosted, and the relevant desk at the Chinese embassy is tasked with selecting and inviting targeted individuals in the host country. For example, the Chinese Ministry of Public Security attaché at the embassy would be responsible for inviting local law-enforcement representatives to join programs organized by the Chinese Ministry of Public Security. At least eleven Chinese government ministries and Party departments have delivered training programs to foreign government officials in the past three years, including the Ministry of Commerce, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ministry of Science and Technology, Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, Ministry of Justice, Ministry of Ecology and Environment, Ministry of Culture and Tourism, National Health Commission, Ministry of Emergency Management, International Liaison Department, and Ministry of Public Security.7“Ministry of Foreign Affairs Lancang-Mekong Cooperation Foreign Assistance Aviation Training Program Inauguration Ceremony,” Civil Aviation Flight University of China, October 13, 2021, https://icd.cafuc.edu.cn/info/1021/1116.htm; “The First International Science and Technology Project Management Talent Training Class Was Successfully Held in Hainan,” Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China, October 12, 2023, https://www.most.gov.cn/kjbgz/202310/t20231012_188449.html;

“‘Lancang-Mekong Countries Digital Economy International Cooperation Training Course’ Was Held in Beijing,” Huaxin Institute, November 22, 2022, https://huaxin.phei.com.cn/news/321.html; “Insert the Concept of Integrity throughout the Entire Process of Jointly Building the ‘Belt and Road,’” Ministry of Justice of the People’s Republic of China, October 24, 2023, https://www.moj.gov.cn/pub/sfbgw/jgsz/gjjwzsfbjjz/zyzsfbjjzyw/202310/t20231024_488285.html; “Addressing Climate Change Risks and Protecting the Marine Environment! This International Training Course Was Held in Qingdao,” People’s Daily, November 29, 2023, https://dzrb.dzng.com/articleContent/31_1222850.html; “The Opening Ceremony of the 2021 Cambodian Chinese Tour Guide Training Course Will Be Held Online,” Ministry of Culture and Tourism of the People’s Republic of China, November 4, 2021, https://www.mct.gov.cn/whzx/whyw/202111/t20211104_928774.html; “The ‘Belt and Road’ National Training Course on Key Technologies and Policy Formulation for Chronic Disease Prevention and Control Was Successfully Held,” International Health Exchange and Cooperation Center of the National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China, September 19, 2023, http://www.ihecc.org.cn/news.html?_=1694574683221; “The Ministry of Emergency Management and the International Civil Defense Organization Hosted a Comprehensive Training Course on Emergency Management in Beijing,” Ministry of Emergency Management of the People’s Republic of China, July 25, 2023, https://www.mem.gov.cn/xw/yjglbgzdt/202307/t20230725_457236.shtml; “Training Course for Local Friendly People in Mongolia Successfully Concluded,” Lanzhou University of Technology, December 28, 2023, https://gjy.lut.edu.cn/info/1180/4178.html; “The 2023 Tajikistan Seminar on Combating Cybercrime Was Successfully Held in Our Institute,” Shanghai Institute of Science and Technology Management, December 28, 2023, https://www.sistm.edu.cn/info/10000.html. According to the files, within each of these Chinese ministries and departments, an “international cooperation and exchange” office then coordinates to subcontract the delivery of the training program to a hosting entity, often with a quasi-civilian Chinese entity with extensive ties to the government. The MOFCOM files show that the 795 training programs were subcontracted to 111 hosting entities in 2021 and 2022.

Given the vast number of Chinese ministries and departments found to have provided trainings to foreign government officials in the past few years, it is reasonable to conclude that these programs were not paused during the pandemic but simply moved to an online format. A review of the 795 descriptions shows that 21,123 individuals participated in online training programs that were provided by MOFCOM in 2021 and 2022. These programs were centered on lectures and included relevant virtual site visits. They ranged from one to 60 days in length: 42 percent of all programs were between twelve and fourteen days, and 34 percent were between 19 and 21 days. Program size was between 15 and 60 participants, and 68 percent of the programs were designed for 25 participants. Based on the training description, nearly all the programs targeted developing countries.

Because this research dataset was limited to program-description files from the MOFCOM, there remain obvious blind spots to understanding the full scope and depth of Chinese governance-export training programs for foreign governmental officials. However, precisely because the dataset here concerns those trainings delivered by the MOFCOM, examination of the files permits unique insights into how the PRC marries economics and politics in its trainings, revealing that Chinese economic achievements are used to support authoritarian ideals.

This report maps the governance practices Beijing is promoting in countries across the Global South. It does not attempt to examine the effectiveness of these efforts, which is outside the scope of this project. Follow-on research endeavors involving local experts will be necessary for exploration of individual governments’ receptivity to PRC narratives and practices, which is likely determined by a mix of local interests and political contexts.

Party governance as the root of all success

Chinese training programs focused specifically on governance practices have traditionally been implemented by the International Liaison Department (ILD), an agency under the Central Committee of the CCP whose core function is party-to-party diplomacy. In its political engagement with other countries’ political parties, the ILD has long conducted training sessions on Chinese governance to promote CCP ideology, with the stated intent to conduct “state governance experience exchange [治国理政经验交流].” Initially such trainings were held exclusively between the CCP and countries with one-party rule or corresponding Leninist party structures, such as Vietnam.8“Jiang Zemin and Le Kha Phieu Held Talks,” Guangming Daily, February 26, 1999, https://www.gmw.cn/01gmrb/1999-02/26/GB/17979%5EGM1-2609.HTM. This is no longer the case. The ILD training sessions have expanded to include sessions in non-communist and non-authoritarian countries. At the same time, other entities in the Chinese government have begun conducting their own “state governance experience exchanges.” In the late 2000s, similar language on “state governance experience exchange” began to surface in foreign policy documents describing engagements with developing regions and countries, including Latin America in 2008, Kazakhstan in 2009, Laos and Myanmar in 2010, and Mongolia in 2011,9“China’s Policy Paper on Latin America and the Caribbean,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, November 5, 2008,

https://www.mfa.gov.cn/web/wjb_673085/zfxxgk_674865/gknrlb/tywj/zcwj/200811/t20081105_7949867.shtml;

“Hu Jintao Held Talks with Kazakhstan President Nazarbayev,”, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, April 16, 2009. https://www.mfa.gov.cn/web/gjhdq_676201/gj_676203/yz_676205/1206_676500/xgxw_676506/200904/t20090416_7978778.shtml; “Xi Jinping Held Talks with Lao Vice President Bounnhang,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, June 16, 2010, https://www.mfa.gov.cn/web/zyxw/201006/t20100616_308470.shtml;

“Chairman Wu Bangguo Meets with Chairman of the National Peace and Development Council of Myanmar Than Shwe,” Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the Republic of the Union of Myanmar, September 22, 2010, http://mm.china-embassy.gov.cn/sgxw/2010news/201009/t20100922_1779679.htm; “Wu Bangguo Meets with Mongolian Prime Minister Batbold,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, June 15, 2011, https://www.mfa.gov.cn/web/gjhdq_676201/gj_676203/yz_676205/1206_676740/xgxw_676746/201106/t20110615_9299059.shtml. demonstrating the expanded reach of Chinese governance training sessions.

Since then, each training, no matter the subject, has contained language on CCP ideology and organization and related contributions to the PRC’s achievements in that subject area. In this way, authoritarian governance choices are being promoted even in the most niche of subject areas.

Even programs on seemingly innocuous topics like beekeeping, bamboo forestry, meteorology, or low-carbon development all begin by briefing participants about the Chinese reform and guiding management principles raised at the latest plenary sessions of the Party committee. The programs highlight where successful tactics for poverty alleviation or pandemic management originated, and then relate these principles to the technical subject areas being covered. This approach is employed to maintain consistency of narrative delivery to a variety of audiences. In the program descriptions obtained, targeted foreign government officials range from the highest political level to the technocratic level, and from senior-level directorships to junior staff members of departments working on political affairs, the economy, education, agriculture, science, and more.

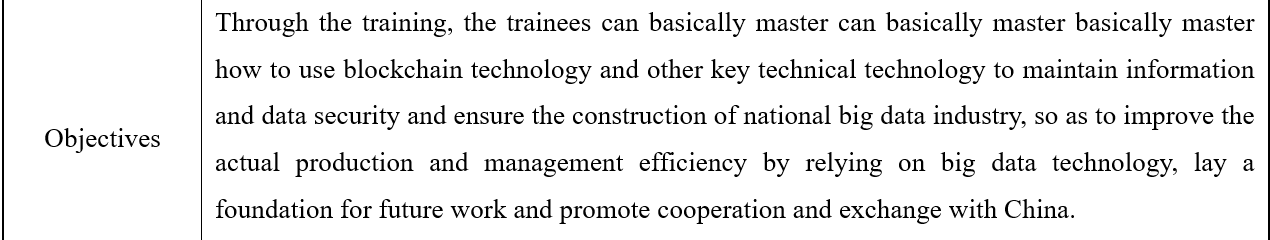

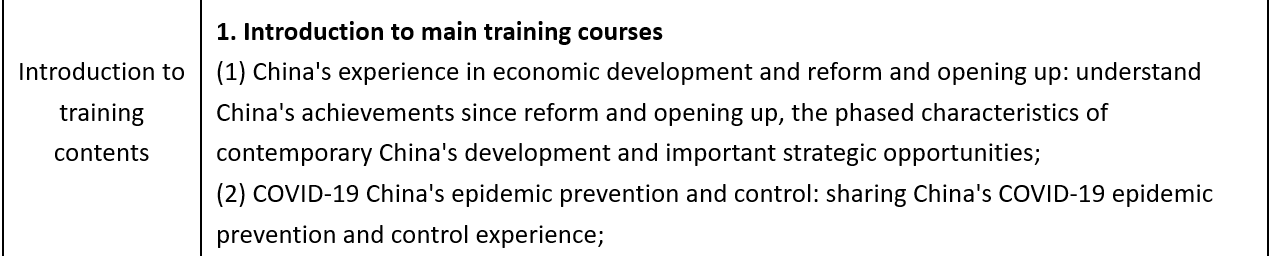

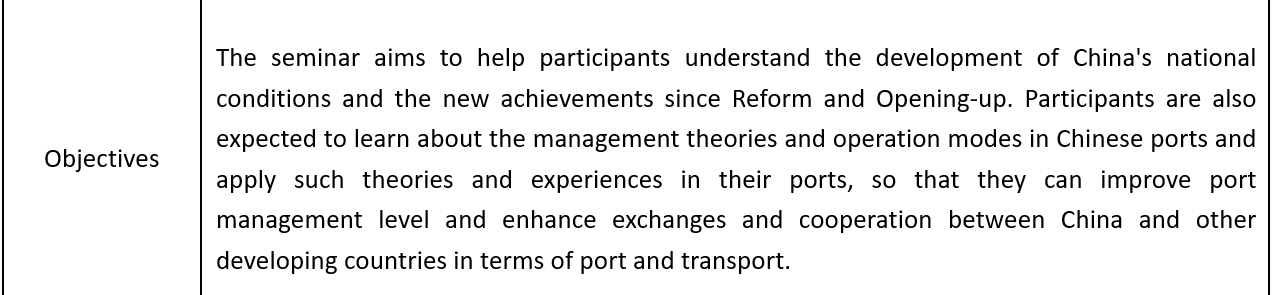

According to a review of the 795 training descriptions obtained in the course of this research project, MOFCOM trainings cover a vast variety of topics, including trade-related areas such as port management, international application of BeiDou (the Chinese global navigation satellite system), and blockchain and information security technologies. However, despite MOFCOM’s remit, it also provides training on topics that do not seem immediately related to trade, such as the role of think tanks for implementing the Belt and Road Initiative, national policy on ethnic minorities, new-media affairs, population management and development, university management, governance practices for presidential advisers, urban governance, social security and welfare, and smart cities.10Smart cities use digital technology to collect data to facilitate the management of public goods delivery. In China, smart cities are developed and guided by authoritarian principles and has the potential to enhance control and monitoring of the Chinese population.

For the purpose of this research, the 795 training programs were reviewed and categorized into six groups based on their reported activities as outlined in the files. The following group labels were created by the author.

1. Clearly authoritarian: The first group describes training programs which include explicit lessons on PRC practices that are widely regarded in liberal democracies as direct infringements on personal freedom. This includes PRC endorsement of non-democratic regime practices in political, government, and legal affairs, including administrative control over the media, information, and population.

2. Potentially authoritarian: These training programs contain lessons on PRC practices which have, in some cases, infringed on personal freedom or indirectly aided infringement of personal freedoms and individual rights. This includes, for example, training on dual-purpose technologies that could be exploited to access individuals’ data in ways that expand state surveillance and control over citizens’ personal lives.

3. Infrastructure and resource access: These training programs are centered on setting standards and imparting industrial technical skills for various aspects of infrastructure and resource extraction, which may further PRC access to critical resources. This includes, for example, renewable energy application, mechanization of the agricultural sector, and technologies in mining, copper processing, and biotechnology.

Intelligence value of the trainings

As detailed in the files, the majority of these training programs, no matter the category, require participants to submit a report prior to the training. The trainings, therefore, provide a reliable intelligence benefit to the Chinese government. Even if an audience does not engage with the program content or demonstrate receptivity to party ideologies and narratives, the reports submitted by participants contain potentially valuable information that Beijing routinely receives en masse. Foreign officials are asked to write about current developments in their country related to the training subject, their country’s current cooperation and partnership with other countries on that subject, and potential ideas for collaboration with the PRC on that subject.

Beyond obtaining immediate, updated, and accurate intelligence from foreign government officials, this approach enables Beijing to assess their future willingness to cooperate on that subject. Specifically, the process directly identifies the scope of potential areas of cooperation from leading experts and officials in charge, prepares the way for potential informal discussion about future cooperation, and, most importantly, identifies individuals who are willing to facilitate and build long-lasting relations with China. With this in mind, this research effort focused on trainings aimed at expanding China’s footprint in the Global South’s infrastructure, resources, information operations, and security domains.

4. Information operation access: These training programs are centered on activities that might further PRC access for its information operations, such as programs on Chinese culture and Mandarin-language promotion for foreign officials.

5. Security access: The fifth group involves and describes training programs centered on activities that may further PRC access to the sensitive security infrastructure of a foreign country, such as programs on aviation emergency, satellite imagery, and geochemical mapping.

6. Others: The sixth group includes all other training programs that do not fit into the above categories, such as pest control, climate change, soybean production, tourism development, and preschool-education sector capacity building.

Among the 795 training courses offered by MOFCOM between 2021 and 2022, about 25 percent of the programs were categorized as clearly authoritarian, 10 percent as potentially authoritarian, 22 percent as related to infrastructure and resource access, five percent as related to security access, two percent as information-operation access, and 35 percent as “others.”

Based on this categorization, the research then focused on examining files of training programs that were not categorized as clearly authoritarian or potentially authoritarian. This revealed the extent to which Beijing used potentially authoritarian means to influence governance choices by injecting narratives that marry authoritarianism with various successes related to the economy. It further demonstrates that PRC training programs that appear to be focused on trade, infrastructure, and other nominally non-political topics are also efforts to promote China’s governance model.

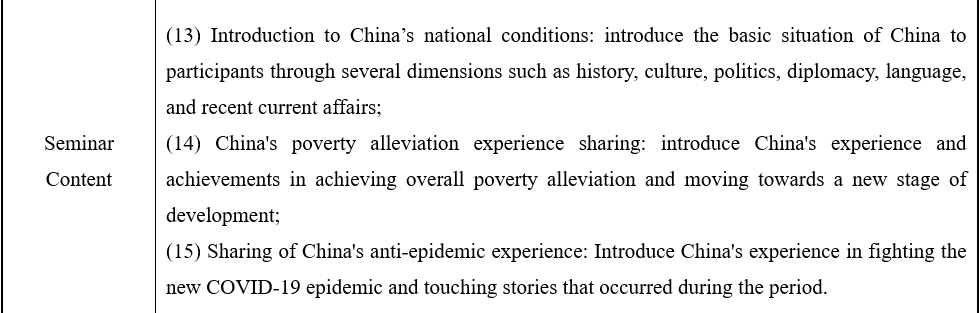

The following are just two examples out of the hundreds of files in which the same pattern can be observed. In one file entitled “Seminar on international application of BeiDou and remote sensing,” and in another, “Seminar on port management for Central and Eastern European countries,” the training content specifies ten and fifteen sub-categories, respectively. At least two or three sub-categories are completely unrelated to the training subject, instead focusing on China’s reform and opening-up process, poverty-alleviation programs, and management of the COVID-19 pandemic, highlighting the success of China’s particular governance model in handling these challenges. The training programs consistently and repeatedly remind trainees across the Global South that all of China’s achievements are attributed to its political choices and authoritarian governance practices.

Despite the lack of access to the exact lecture materials used in these programs, a review of the list of instructors yields insights into the kind of narratives the lecturers delivered to foreign governments. For example, Dr. Ding Yifan (丁一凡) was one of six instructors for the 13-day training on port management. A researcher at the state-backed Development Research Center of the State Council, Ding has written in support of internationalizing China’s currency to bypass “Western control” over financial mechanisms and setting up overseas Chinese economic zones to relocate parts of Chinese production to developing countries before commodities are finalized for export to Europe and North America, ensuring China’s stake in the global supply chain and embedding Chinese assets abroad.11“Ding Yifan: Promoting RMB Internationalization Will Help Ensure Financial Security,” Xinhua, Janurary 20, 2023,

http://www.news.cn/world/2023-01/20/c_1211720561.htm; “Ding Yifan: ‘One Belt, One Road’ Adds Momentum to Developing Countries,” Economic Daily, October 26, 2020,

http://www.china.com.cn/opinion/think/2020-10/26/content_76844794.htm. These are positions commonly held by many Chinese academics and experts.

Ding, however, also has a more distinctive track record as an advocate for China’s authoritarian system. For example, in a lengthy 2017 online lecture titled “Advantages of the Chinese system of governance” (“中国的制度优势”)12“丁一凡:中国的制度优势” 71cn, January 16, 2017, http://www.71.cn/2017/0116/930687_9.shtml., Ding explicitly explained that the Chinese economic miracle is a result of “a good democratic system of socialist governance with Chinese characteristics, our democracy is the real democracy” (“是因为中国特色社会主义民主制度好,我们的民主是真正的民主”) and that “sometimes people don’t know how their own society should develop, and they need to be guided by strong leaders to show the way.”( “有时候民众并不知道他们希望社会朝哪个方向发展,需要强有力的领导人去指明方向.”) Ding’s online lecture details flaws in voting-based democratic systems, pointing to the constant change of governments and party politics as inefficient and a waste of resources. Ding makes the case that one-party authoritarian politics is the only feasible system for China: “We are a multi-ethnic, multi-cultural country. If we have multi-party politics, then our country will break apart and fall into civil war, destroying all we have built.” (中国是一个多民族、多文化国家,如果实行多党政治,那么,一定会四分五裂,陷入严重的内战,毁掉我们建国以来所做的一切努力.) Ding has also fueled disinformation against Japan and the United States, claiming Japan dared “to release nuclear-contaminated water because it has the backing of the United States” (日本胆敢排核污水底气在于背后老板是美国人) when Tokyo released wastewater from the Fukushima nuclear plant that was hit by a tsunami in 2011 after receiving approval to do so from the International Atomic Energy Agency.“13The science behind the Fukushima waste water release,” BBC, August 26, 2023, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-66610977#:~:text=Japan%20is%20releasing%20the%20waste,take%20at%20least%2030%20years; “China nuclear plants released tritium above Fukushima level in 2022, document shows,” Japan Today, March 10, 2024, https://japantoday.com/category/politics/china%27s-nuclear-plants-released-tritium-above-fukushima-level-in-2022.

“Translation Result Ding Yifan: Japan Dares to Discharge Nuclear Sewage Because the Boss behind It Is an American,” Global Times, August 31, 2023, https://news.hebei.com.cn/system/2023/08/31/101202041.shtml.

Global implications and recommendations

The findings catalogued in this report underscore that the PRC is engaged in a concerted effort to promote authoritarian governance across the developing world, using its own economic success as the primary argument for why countries need not adopt “Western” democratic practices to achieve their development goals. This is occurring across Chinese training programs in Global South countries, regardless of the often-unrelated subjects purportedly addressed. While Beijing often suggests that countries should pursue approaches specific to their own local contexts, rather than adopting the Chinese model completely, PRC trainings clearly highlight aspects of its authoritarian model as central to the blueprint of successful development that others can emulate.

China is likely to continue expanding training efforts to promote autocratic governance. Numerous training programs currently conducted in China for foreign government officials are already being moved to countries across the Global South, with new Chinese institutions set up to deliver programs that are both longer term and more sophisticated. In 2022, a Chinese political leadership school was opened in Tanzania, delivering the same type of governance training program outlined above that marries authoritarianism with economic success.14“Enter the Nyerere Leadership Academy,” People’s Daily, December 20, 2023, http://www.people.com.cn/n1/2023/1220/c32306-40142820.html. If successful, this kind of setup is likely to be recreated elsewhere. For example, Luban Workshops were introduced in 2016 as a vocational equivalent of the Confucius Institutes and there are now 27 workshops worldwide, an increase from 18 in 2021.15“Director Luo Zhaohui Accepted China Daily’s ‘Committee Says,’” China International Development Cooperation Agency, March 7, 2024, http://www.cidca.gov.cn/2024-03/07/c_1130086359.htm; Niva Yau and Dirk van der Kley, “China’s Global Network of Vocational Colleges to Train the World,” Diplomat, November 11, 2021, https://thediplomat.com/2021/11/chinas-global-network-of-vocational-colleges-to-train-the-world/. Where Confucius Institutes are state-sponsored centers teaching Chinese language and culture, Luban Workshops are state-sponsored classrooms teaching Chinese industrial skills and standards. Given the findings in this report, it is reasonable to assume these workshops will weave lessons on the benefits of China’s authoritarian model into vocational classes.

Beijing’s growing drive to promote its model appears unaffected by the marked slowdown in China’s economic growth and the well documented structural challenges facing China’s economy, many of which are a result of an authoritarian system under the CCP that increasingly prioritizes political control and absolute security over unleashing the power of market innovation and consumer demand.16Daniel H. Rosen and Logan Wright, “China’s Economic Collision Course,” Foreign Affairs, March 27, 2024,

https://www.foreignaffairs.com/china/chinas-economic-collision-course. In other words, the very example at the heart of China’s promotion of authoritarian governance—its own remarkable development since the late 1970s into the world’s second largest economy—may be falling apart.

Many developing countries, however, are not attuned to the mounting challenges China is facing and still value the lessons of the country’s success under authoritarian rule, presenting ample opportunities for the PRC to expand and deepen its training programs across the Global South. The potential implications of these continued efforts are significant and wide ranging.

First, more countries may entertain and potentially adopt authoritarian governance practices shared by Beijing as they seek the potential benefits of economic engagement with China. More research is needed to determine the ultimate impact of China’s governance trainings abroad on recipient countries’ political practices. However, foreign leaders already routinely accept and endorse Beijing’s perspective on Chinese domestic issues and international positions in the hopes of maintaining or increasing Chinese investment and contributions to their nation’s domestic development.17When US Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi visited Taipei in August 2022, following condemnation by Chinese officials, Chinese embassies around the world released public statements and Chinese ambassadors wrote opinion pieces about the visit wherever they could. This prompted many countries to release public statements reassuring Beijing and reaffirming their positions on Taiwan. Beijing orchestrated similar reactions ahead of the boycott of the Beijing Winter Olympics. See: Anouk Wear, “China’s Universal Periodic Review Tracks Its Influence at the UN,” Jamestown Foundation, January 19, 2024, https://jamestown.org/program/chinas-universal-periodic-review-tracks-its-influence-at-the-un/; “The Costs of International Advocacy China’s Interference in United Nations Human Rights Mechanisms,” Human Rights Watch, September 5, 2017, https://www.hrw.org/report/2017/09/05/costs-international-advocacy/chinas-interference-united-nations-human-rights. As China’s combined economic and political influence mounts, more countries dependent on China will likely welcome its lessons and may even sacrifice their own immediate interests in return for the long-term promises that Beijing offers. In some cases, China’s success in “elite capture”—the extensive corruption of a country’s key political and business leaders, resulting in their serving China’s interests above those of their own citizens—will likely contribute to local officials’ willingness to welcome Chinese trainings. The elite capture dynamic may also increase the likelihood that lessons learned in these trainings will be incorporated into their country’s governance practices.

Second, China’s clear propaganda effort through these trainings will combine with the CCP’s broader effort to shape narratives in countries around the world regarding China’s successes and the benefits of engagement with the PRC to advance Beijing’s preferred messaging. Beijing is engaged in a global propaganda effort to “tell China’s story well,”18James T. Areddy, “New ways to Tell China’s Story,” The Wall Street Journal, October 23, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/livecoverage/china-xi-jinping-communist-party-congress/card/new-ways-to-tell-china-s-story-JXt9XFnnegpB7yzmhFNT. as Xi has put it, and counter decades of perceived dominance of the global information space by the United States and other developed democracies, including regarding the legitimacy of non-democratic governance systems such as its own. Included in this endeavor are efforts to train and cultivate local journalists to write positive stories about China, insert official Chinese propaganda in local media outlets, deliver tailored disinformation regarding the United States and the failings of democratic governance19Donie O’Sullivan, Curt Devine, and Allison Gordon, “China is using the world’s largest known online disinformation operation to harass Americans, a CNN review finds,” CNN, November 13, 2023, https://www.cnn.com/2023/11/13/us/china-online-disinformation-invs/index.html., and deploy United Front groups20Those affiliated with the United Front Work Department of the Central Committee of the CCP are tasked with engaging foreign individuals and organizations to achieve and maintain Beijing’s objectives. to co-opt local elites.21For examples of overseas activities of the United Front Work Department, see: “How the People’s Republic of China Seeks to Reshape the Global Information Environment,” US Department of State, September, 2023, https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/HOW-THE-PEOPLES-REPUBLIC-OF-CHINA-SEEKS-TO-RESHAPE-THE-GLOBAL-INFORMATION-ENVIRONMENT_Final.pdf; Alexander Bowe, “China’s Overseas United Front Work Background and Implications for the United States,” U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, August 24, 2018. For Ministry of State Security overseas conduct, see: “Nepali Security Authorities Identify a Chinese Intelligence Agency Official Involved in Anti-MCC Propaganda,” Khabarhub, November 12, 2021, https://english.khabarhub.com/2021/12/219645/. Across these efforts, Beijing’s messaging consistently underscores its development successes while ignoring inconvenient statistics about China’s more recent economic downturn, reinforcing the notion that countries in the Global South might benefit from following China’s developmental path.

Third, China’s expanding promotion of authoritarian practices may foster greater ideological and political polarization globally as democracy’s presumed status as the ideal form of government is thrown into greater doubt. Even if most countries exposed to CCP trainings do not adopt a wholesale authoritarian approach to governance, the selective adoption of aspects of China’s system will mean that more countries choose not to align with the United States and other democracies on a range of policy choices that will shape global governance and connectivity. For example, a number of countries have been inspired to adopt aspects of China’s top-down regulatory policies on the internet.22“Thailand Tilts Towards Chinese-Style Internet Controls,” Bangkok Post, April 15, 2019, https://www.bangkokpost.com/thailand/general/1661912/thailand-tilts-towards-chinese-style-internet-controls; “New Year, New Repression: Vietnam Imposes Draconian ‘China-like’ Cybersecurity Law,” South China Morning Post, January 1, 2019, https://www.scmp.com/news/asia/southeast-asia/article/2180263/new-year-new-repression-vietnam-imposes-draconian-china. This dynamic is complicating efforts to maintain a more united approach to internet management, potentially fragmenting the internet into competing technospheres. More fundamentally, potential PRC success in encouraging more sympathetic views of autocratic methods—and critical views of democracy—across the Global South would gradually undermine the ability of the United States and other democracies to credibly speak of a common future and interests among countries bonded by democratic values and aspirations.

The first step in addressing these dynamics is to recognize the extent of the problem, conducting further studies such as this one on the nature of various PRC efforts to promote its model and then, most critically, determining the actual impact of these efforts in increasing developing countries’ acceptance, adaptation, and implementation of authoritarian governance practices.

Local interests, political context, and feasibility of adaptation are all reasonable major factors that determine whether a government will ultimately import authoritarian practices and narratives. Only once the effectiveness of various PRC activities has been determined should significant effort be directed at developing tailored measures to counter them, thereby avoiding unnecessary expenditure of very limited resources on addressing the large and expanding number of CCP efforts across countries.

Even as such studies are undertaken, the United States and other democracies should increase efforts to address the relative paucity of knowledge and objective information about China and its approach to governance at home in the majority of developing countries. This lack of reliable, home-grown information on China is perhaps the PRC’s greatest asset in its efforts to promote its authoritarian model because it allows Beijing to set the dominant narrative in many countries regarding China’s rapid economic development and the role of its governance system in that achievement.

As noted, in PRC training programs, foreign government officials are fed disproportionally positive economic stories about China in an environment where Beijing is able to censor as it pleases, creating an illusion of near perfect implementation. This bolsters the strong impressions still held by many across the Global South about the Chinese economic miracle from decades ago and the discourse around authoritarian performance legitimacy.23The author lived and worked in Central Asia on issues related to the PRC between 2018 and 2023. Additionally, the author has previously taken research trips to Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia, India, Sri Lanka, Georgia, and Columbia to learn about local and regional PRC-related issues from local experts. It is essential that more developing countries have access to objective information on current realities in China, including the country’s economic downturn, particularly given concurrent PRC efforts to shape media ecosystems and narratives on China and leverage coopted elites.24“Countering China’s Information Manipulation in the Indo-Pacific and Kazakhstan,” International Republican Institute, June 27, 2023, https://www.iri.org/resources/countering-chinas-information-manipulation-in-the-indo-pacific-and-kazakhstan/.

Relatedly, it is necessary to assist countries across the Global South in cultivating and promoting authoritative expertise on China, to ensure that local voices are offering objective analysis of China’s domestic affairs, governance practices, and engagement abroad. This local expertise is also critical for broadening public and elite understanding of PRC policies and affairs that is not accessible through simply translating Chinese government documents that may be unintelligible to the uninformed. For decades, the Chinese government has tried to influence the development of authoritative foreign voices on PRC affairs, relying on PRC-educated China experts as elite proxies to distribute its narratives, set agendas, and influence foreign policymakers and the public alike. In the Global South, Beijing often controls who can study and develop an authoritative voice on PRC affairs by monopolizing the means to visit and research China, study Chinese language, and access research materials through PRC institutions.

One crucial step toward addressing this problem in the medium to long term is fostering more opportunities for independent research on PRC issues, providing alternatives to PRC-sponsored education. Countries with vast non-PRC-sponsored expertise on China should expand their global outreach, including programs for students from countries across the Global South who may wish to undertake professional Chinese studies outside of the PRC. Such independent expertise is essential to fostering objective discussions on China and competing perspectives that allow the public and their leaders to make informed judgments about the kind of Chinese success they want to replicate.

Lastly, at the basic level, countries across the Global South must be encouraged to create a debriefing process for all returning officials who take part in a PRC training program to determine and catalog the level of effort to shape perceptions and decision-making in different policy areas, including regarding authoritarian governance practices, as well as the extent to which related reporting serves China’s intelligence collection efforts.

China’s promotion of authoritarian governance and undermining of support for democratic practices and principles is likely to increase across the Global South, with Beijing further scaling up the type of trainings documented in this report. This effort is integral to the PRC’s drive to transform a global order currently predicated on the centrality of democracy and individual rights to one more “values-agnostic” and thus suited to China’s rise under authoritarian CCP rule. To counter this effort, countries across the Global South should be encouraged to make independent, informed decisions about their own development path, with access to objective information about China’s political system, domestic affairs, and economic trajectory. Despite democracy’s evident flaws, it remains the system of governance overwhelmingly preferred by publics around the world.25“Democracy Remains Popular but People Worldwide are Questioning its Performance,” Gallup International Association, April 6, 2024, https://www.gallup-international.com/survey-results-and-news/survey-result/democracy-remains-popular-but-people-worldwide-are-questioning-its-performance. Beijing’s revisionist efforts to popularize autocracy will fail if citizens in the Global South have the freedom and information to determine the sort of government under which they want to live.

About the author

Acknowledgement

The author thanks Rana Siu Inboden and other participants at a May 2024 workshop Understanding China’s Authoritarian Projection: Training and Normative Propaganda with Other States, organized by the Robert Strauss Center for International Security and Law at the University of Texas at Austin, for feedback and review of an earlier draft.

Dataset of Chinese government files

These are 14 training program description files from the full dataset of 795, with personal identifying information removed, but remaining available upon requests for research purposes. The English-language text following the Chinese text is entirely written by the program description planner, not the author, and may consist of broken translation. We are currently planning to release all 795 of the remaining training program descriptions and the other administrative files related to their logistics.

- Marine geologic survey and coastal protection training class

- Seminar on blockchain and information security technology for developing countries

- Seminar on enhancing university governance for developing countries (online)

- Seminar on ethnic policies and practices for Belt and Road countries

- Seminar on international application of Beidou and remote sensing

- Seminar on inviting heads of foreign volunteer organizations to China

- Seminar on planning capability of safe city for African countries

- Seminar on population and development program for developing countries

- Seminar on port management for Central and Eastern European countries

- Seminar on national governance for presidential advisers of developing countries

- Seminar on new-developing urban governance for developing countries

- Seminar on new media for Belt and Road countries

- Seminar on social security and social welfare for developing countries

- Seminar for think tank scholars of the Belt and Road countries

Explore the program

The Global China Hub tracks Beijing’s actions and their global impacts, assessing China’s rise from multiple angles and identifying emerging China policy challenges. The Hub leverages its network of China experts around the world to generate actionable recommendations for policymakers in Washington and beyond.

Image: President Xi Jinping at the China-Africa Leaders Round Table at the conclusion of the 15th BRICS SUMMIT in Johannesburg. Photo: GCIS