A new energy strategy for the Western Hemisphere

In 2019, the Atlantic Council’s Global Energy Center and Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center began an effort in partnership with the United States Department of Energy to consider a fresh approach to energy in the Americas that is comprehensive in nature and targeted in its approach. Following a year-long period of engagements alongside six representative stakeholder countries participating, the resulting report: “A New US Energy Strategy for the Western Hemisphere,” was launched in March 2020 and will serve as the launch point for additional work by the Atlantic Council on energy and sustainability issues across the hemisphere.

Table of contents

- Introduction

- The global context

- US interests

- The needs of the hemisphere

- A new US energy strategy for the Western Hemisphere

Foreword

As Secretary of Energy, I have a strong appreciation for the strategic importance of the Western Hemisphere to US prosperity, energy, and national security. As our closest neighbors and strongest trading partners, the energy and economic security of the hemisphere is critically linked to our own.

The Americas are full of potential. With the leadership of the US Department of Energy (DOE) in partnership with our interagency colleagues, the US private sector, and our regional partners, we can galvanize the Western Hemisphere into an energy powerhouse. Achieving the full potential of our hemisphere’s energy resources will boost the economy of the United States and our neighbors while also serving as a counterweight to foreign adversaries.

To help achieve this vision, DOE commissioned the Atlantic Council to conduct independent analysis and develop recommendations on how the Department can most effectively catalyze the development and expansion of energy projects across North America, Central America, South America, and the Caribbean.

The resulting report, A New Energy Strategy for the Western Hemisphere, will inform DOE’s approach to energy engagements in the Western Hemisphere in 2020 and beyond.

I am thankful for Atlantic Council and the thought leaders they consulted for their contributions to this report. I look forward to working with them and others as DOE continues to strengthen the energy security and prosperity of the Western Hemisphere.

Sincerely,

Dan Brouillette

Secretary

US Department of Energy

I. Introduction

The Western Hemisphere has a unique advantage in global energy markets. It is rich in natural resources, from conventional fuels such as oil and natural gas, to critical minerals such as lithium for batteries. The region is also poised to become a leader in newer and emerging energy resources. It has, for example, abundant potential for solar and wind energy and other advanced energy technologies, such as nuclear energy. It enjoys high and rapidly growing levels of renewable energy, especially in power generation, largely based on significant levels of legacy, utility-scale hydropower.1Sergey Paltsev, Michael Mehling, Niven Winchester, Jennifer Morris, and Kirby Ledvina, Pathways to Paris: Latin America, MIT Joint Program Special Report, 2018, https://globalchange.mit.edu/sites/default/files/P2P-LAM-Report.pdf. Many of the Americas’ subregions share cross-border electric power or liquid fuel interconnections. The vast majority of its nations share common values, including a commitment to democracy, the rule of law, and shared prosperity. The countries of the Americas are bound together through market-based trade, mutual investment, and deep cultural and security ties. Moreover, the hemisphere is indispensable to US energy security. The United States derives the majority of its imports of oil, gas, and electricity from its neighbors and there is considerable potential for trade in increasingly high-value minerals.

The region’s energy profile is heterogeneous, both in terms of resource endowment, national needs, and energy challenges. The region has been an incredible laboratory for experimentation in the clean energy transition. For example, Argentina, Chile, and Mexico have pioneered reverse auctions with great success. Five countries have employed some form of carbon pricing or emissions trading schemes to incentivize investment in new and lower-emission power generation.2Specifically, countries with some form of national level carbon pricing in the region include Canada, Colombia, Mexico, Chile, and Argentina. “Carbon Pricing Dashboard,” the World Bank, accessed November 17, 2019, https://carbonpricingdashboard.worldbank.org. Argentina, Canada, and the United States have seen tremendous success in unconventional hydrocarbon exploration and production, while Brazil and Guyana have seen major successes in offshore exploration. This diversity of experience shows that the countries in the region have much to learn from each other.

The region also has many common challenges. In a global economy that is currently enduring weak economic growth, uncertain energy demand, and stiff competition for investment, nations face serious challenges as they compete for new investment in electricity, energy transportation, and energy services, notably in the oil and gas sectors. Many of the region’s economies have frameworks laboring under macroeconomic distortions such as federal budget imbalances or persistent external current account deficit, as well as microeconomic distortions such as subsidized power or product prices, and a lack of competition in the energy markets.

The United States, led by the Department of Energy (DOE), can be a leader in gathering partners around the hemisphere. It can bring to bear a wide range of US government tools in an effort to dramatically enhance energy investment in the hemisphere and thereby expand energy access, affordable power, energy security, and national prosperity. By sharing best practices and lessons learned, enabling informed conversations and promoting cooperative engagement on overcoming investment barriers, highlighting investment opportunities, and supporting its neighbors and friends with technical assistance, capacity building training, and mustering the many programs that can support energy development, the United States can help raise the global competitiveness of the hemisphere, advance its shared prosperity, and improve US national and energy security as a result.

This report recommends a new US energy strategy for the Western Hemisphere to achieve these ends. The report itself is the product of an extensive hemispheric collaboration. We held strategy sessions, roundtables, and one-on-one meetings with government leaders from Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Colombia, Guyana, and Mexico, as well as private sector investors, financiers, and civil society members from these countries and the United States. This spirit of partnership is deeply embedded in the report, as we hope it will be in the partnership ahead.

II. The global context

The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that the world invested $1.8 trillion in the energy sector and related projects in 2018.3World Energy Investment 2019, International Energy Agency, May 14, 2019, https://www.iea.org/wei2019/. Its baseline projections anticipate average annual investment in energy of $2.2 trillion through 2025, and considerably more in its decarbonization scenarios.4Ibid; World Energy Outlook 2018, International Energy Agency, November 13, 2018, https://www.iea.org/weo2018/. The competition for that capital, in terms of fuel source, technology end use, and even regional destination, will be intense. The highest energy demand is in Asia, led by China and India, and accordingly, much investment is targeted at those rapidly growing markets. Moreover, the global economy is entering a phase of slower growth. In the Western Hemisphere, growth is modest or flat. Expectations for levels of global hydrocarbon demand are uncertain. The success in improving the productivity of unconventional oil and gas development, added to expectations of softening oil prices, makes the threshold for new investment in oil and gas competitive, especially when long-term commitments are required. In this environment, the competition for project investment is intense.

To its advantage, the hemisphere is well positioned to overcome these headwinds and attract international capital, if it chooses to compete. The nations of the hemisphere are engaged in a major energy transition. They are increasingly seeking to modernize and decarbonize all aspects of their energy systems, develop their native natural resources, and expand their energy transportation networks. Many of these nations seek to extend reliable, affordable, and industrial-scale power access to support economic and human development throughout rural and remote areas in a bid to enhance local prosperity and narrow the rural-urban divide. In the electricity space, improvements in solar and wind technology have made these fuel sources more attractive to governments and utilities.

The development of “mini” grids is making distributed electricity more accessible. Floating storage and regasification units (FSRUs) have lowered the cost of entry for new or small-scale natural gas consumers and accelerated the ability of countries to transition away from higher carbon fuels, such as diesel. Compared to other regions, the countries in the Western Hemisphere are relatively politically stable, respect the rule of law, and generally enjoy peaceful relations with their neighbors. There are significant interconnections between many of the major economies, as well as the long-standing, close trilateral relationship among Canada, Mexico, and the United States. But in recent years, we have seen a cooling of investment in the electricity, energy transportation, and oil and gas sectors in many countries undergoing political transitions due to investor uncertainty about the direction and stability of macroeconomic and legal frameworks. Similarly, in many countries, a company’s social license to operate (SLO) is increasingly challenged over land use, fear of detrimental impacts of development, and questions about whether the impacts of infrastructure siting are just in light of broader environmental concerns (such as land, air, and water quality). Canada and Mexico are seeking to build new relationships with their indigenous peoples and that is changing how energy projects must engage with these communities and respect their rights. In order to attract the levels of investment sought by countries’ leaders (and their stakeholders) for electric power and critical mineral and hydrocarbon development, the nations of the hemisphere must become more attractive and competitive than they are today.

III. US interests

The United States has powerful national interests in helping the nations of the hemisphere achieve energy security and in enhancing regional prosperity. Canada and Mexico are the United States’ largest trading partners and the United States has extensive trading relationships throughout the rest of the region as well. Canada, in particular, is the largest foreign supplier of energy to the United States, providing one in five barrels of oil consumed in the United States and sharing one of the most highly integrated electricity grids in the world. The United States Trade Representative (USTR) notes that, as of 2018, the United States’ total goods and services trade within the Western Hemisphere was $1.9 trillion.5“Western Hemisphere,” Office of the United States Trade Representative, accessed November 18, 2019,

https://ustr.gov/countries-regions/americas. The United States’ national security is enhanced by ensuring that its neighbors, nearly all democracies, enjoy new opportunities for prosperity. In a world where illiberal and anti-competitive market practices are on the rise, the United States can support fellow market economies by helping them enhance self-sufficiency and development. By promoting economic development through energy development, particularly in Central America, the United States can also help ameliorate some of the root causes of migration from the region.

Finally, US energy security, or rather the ability to access the energy the United States needs at affordable prices, has long depended on successful and reliable energy trade. The United States has depended on Canada, Colombia, Mexico, and (prior to US sanctions) Venezuela for heavy crude imports, and previously relied on Canada for natural gas. Many US states, particularly in the Northeast, are considering expanding low-carbon electricity imports from Canada. Many countries in the region, particularly Canada, also offer important access to critical raw minerals. On a global level, the contributions of the hemisphere (increasingly led by the United States as an energy producer) are indispensable to energy security.

IV. The needs of the hemisphere

Just as the histories, geographies, and economic power of the countries of the Western Hemisphere vary considerably, their energy needs and respective challenges are also highly varied. Some countries are historically robust conventional energy producers, while others have had tremendous success managing their energy needs using high levels of legacy renewables (specifically hydropower) and integrating more recent additions of variable renewables. Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Canada, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, Peru, and the United States are significant producers of oil and/or natural gas. Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, and Mexico have held highly successful renewable energy auctions and taken strides to add newer unconventional fuels (e.g., biofuels such as ethanol) into their energy mixes. Nevertheless, some serious endemic problems persist. The nations of Central America and the Caribbean endure (to varying degrees) high levels of energy insecurity. They suffer from high energy costs, reliance on expensive and often highly polluting fuel resources, high electricity prices, and modest local resource hydrocarbon endowments. In addition to these endemic challenges, many of these countries are very small in geographic size and population, making the challenge of generating economies of scale for energy all the more difficult.

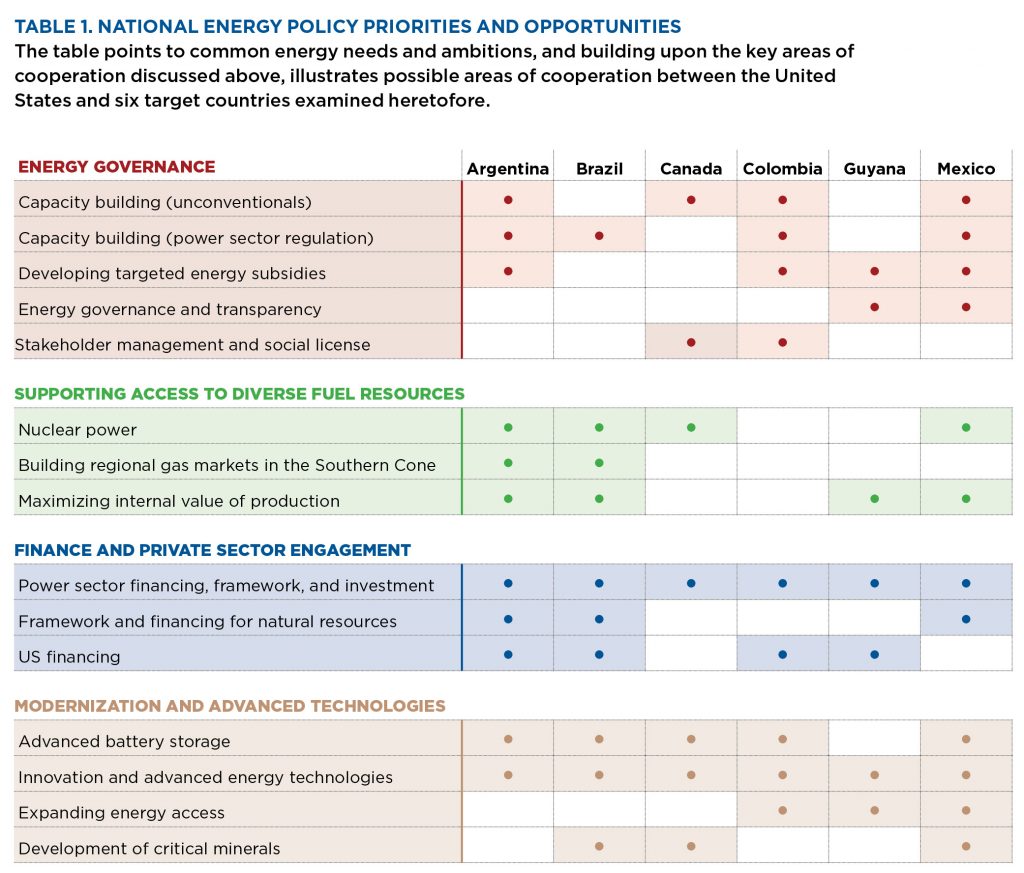

As a sample of the hemisphere’s nations, we consulted with Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Colombia, Guyana, and Mexico to understand their immediate concerns, their perspectives on regional cooperation, and their views on the benefits of deeper partnership with the United States. We describe their concerns as an illustration, albeit not an exhaustive one, of the needs of the hemisphere at large and to draw inferences as to the key areas on which a new US energy strategy for the Americas should focus.

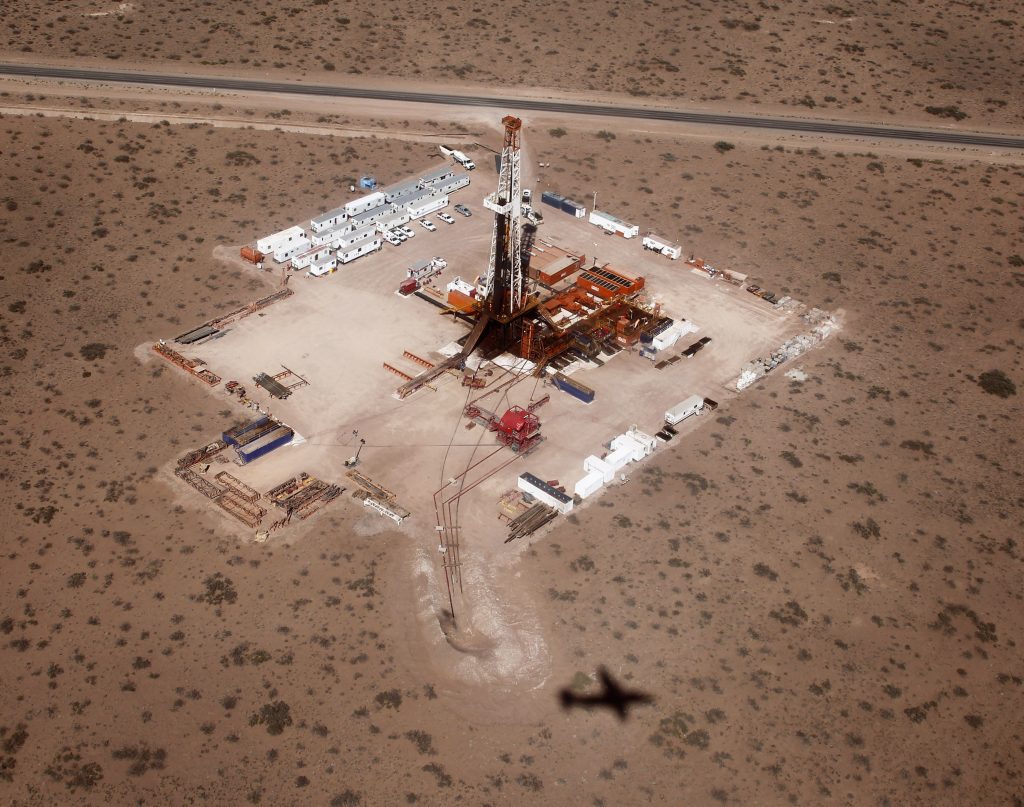

Argentina

Argentina is enjoying marked success attracting investment to its potentially massive Vaca Muerta hydrocarbon project, as well as in offshore oil exploration. It is already a major destination for US foreign investment. However, Argentina presently lacks appropriate energy transportation infrastructure to move hydrocarbons from the Neuquén Basin (Vaca Muerta Formation), where shale gas is being developed, to its demand centers and export facilities. A new transmission pipeline is being tendered, but the awarding process has been postponed due to the change of administration in the country. Natural gas demand is highly variable by season. Argentina would benefit from developing energy storage, but financing and siting that storage is a challenge, as is the development of appropriate and adequate price signals.

In the electricity space, Argentina has been a pioneer in attracting renewable energy investment through its RenovAr program, as well as a growing nuclear energy program. While generation capacity is adequate to meet the current internal demand, Argentina needs new transmission capacity to receive and distribute these new sources of generation with minimal losses or needs to increase its generation capacity to reach exportable surplus. An additional challenge is regulatory design, specifically devising ways to balance the energy mix in Buenos Aires so that intermittent renewable energy is complemented with flexible power to ensure greater reliability. Argentina is seeking ways to increase the utilization of the natural gas it will eventually produce, possibly by developing new and lucrative petrochemical and fertilizer industries, as well as expanding the use of natural gas for transportation (such as a second wave of compressed natural gas (CNG) conversions and the construction of blue highways for trucks using mini liquefied natural gas (LNG) plants). Argentina has also resumed gas exports to Chile and seeks to increase exports to Brazil, and recognizes the need to overcome historical concerns about the security of its supply. More broadly, Argentina faces the challenge of managing tensions among proper pricing of energy, addressing subsidies without overburdening low-income stakeholders, inflation, and currency depreciation—often resulting in limited financing options and high costs where options exist despite the clear need for greater investment.

Brazil

Brazil has a diverse and robust energy economy. It enjoys high levels of hydropower supply, new investment in a range of forms of renewable energy, and possesses extensive experience as a major oil producer. It is a major destination for US investment, as well as a partner in multiple aspects of regional security, including energy security and defense. Its major priorities for collaboration are in oil and gas, energy efficiency, nuclear energy, and biomass. Brazil is on a campaign to further develop its native energy resources and significantly reduce the role of state-owned Petrobras in the production of oil and gas and the ownership of pipeline infrastructure. While Brazil will see major increases in natural gas production, this production is in some cases hard to deliver to its major demand centers in the southeast or underserved areas, such as the northeast. Designing a framework to increase investment in pipeline infrastructure (currently half the size of Argentina’s) is also a major priority.

Canada

Canada is a major global energy producer with highly diversified energy resources. It serves as the world’s second-largest producer of hydroelectricity and uranium, the fourth-largest producer of crude oil and natural gas, and holds the world’s third-largest oil reserves. Canada’s electricity generation is currently 80 percent non-emitting, one of the cleanest in the Group of Twenty (G20). Canada’s domestic priorities include achieving net zero emissions by 2050, while continuing to expand markets for energy resources and technologies. This strategy includes innovating to continue to reduce emissions from the petroleum sector, an approach that has led per barrel emissions from Canada’s oil sands to fall 32 percent since 1990.6“7 facts on the oil sands and the environment,” Natural Resources Canada, accessed February 6, 2020, https://www.nrcan.gc.ca/energy/energy-sources-distribution/crude-oil/7-facts-oil-sands-and-environment/18091.

The US and Canadian energy systems are closely integrated. In 2018, the United States accounted for 89 percent of Canadian energy exports, which represented 24 percent of US uranium consumption, 21 percent of oil consumption, 11 percent of natural gas consumption, and 2 percent of electricity consumption.7Energy Fact Book 2019-2020, Natural Resources Canada, 2019, https://www.nrcan.gc.ca/sites/www.nrcan.gc.ca/files/energy/pdf/Energy%20

Fact%20Book_2019_2020_web-resolution.pdf. Canada and the United States promote free trade in all forms of energy, including through provisions included in the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) and the associated Canada-US Side Letter on Energy.

Expanding the network of thirty-four oil and gas pipelines and seventy-four electricity transmission lines that cross the Canada-US border will strengthen regional energy security by facilitating flows of oil, gas, and low-carbon electricity between Canada and the United States, allies who share market-based approaches to energy development. Given the high levels of investment in government research and development in energy in the United States and Canada, there is great opportunity to coordinate, collaborate, and harmonize these projects and optimize efforts. Strong bilateral cooperation is already underway in the area of carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS); hydrogen; advanced materials for clean energy; and next generation nuclear, such as small modular reactors. Canada also works closely with partners throughout the Americas, both through multilateral fora like the Clean Energy Ministerial and bilateral agreements with Chile, Colombia, Guyana, and Mexico.

Colombia

Colombia is a long-standing destination for US investment and a major security partner for the United States. Colombia’s energy priorities are attracting private sector investment to revive its declining oil and gas production, increasing the share of renewables in its power generation mix, and expanding access to electricity to achieve 100 percent coverage, especially in remote areas. Given its history of subsidized electricity, Colombia is focused on providing a new framework that will secure financing for new power generation. Despite some challenges at auctions earlier in 2019, Colombia awarded 1.3 gigawatts (GW) of solar and winds contracts in its inaugural October 2019 renewable energy auctions.8Tom Kenning, “Colombia awards 1.3GW of solar and wind in ‘historic’ first auction,” PV Tech, October 23, 2019, https://www.pv-tech.org/news/colombia-awards-2.2gw-of-solar-and-wind-in-historic-first-auction. Colombia has also launched an Energy Transformation Task Force to propose strategies to bring energy to remote areas, facilitate more competitive market structures, define a role for natural gas in Colombia’s energy transition, use advanced digital technology to manage energy demand, and update its energy regulatory frameworks.

Key areas of potential cooperation include understanding best practices in unconventional resource development and more effective engagement with stakeholders in areas where the country seeks to develop unconventional oil and gas deposits, and also understanding best practices to include new technologies in the power market. Colombia has also asserted regional leadership on decarbonization and the energy transition. In September 2019, Colombia announced its cornerstone role in a new Latin American initiative featuring a collective target for 70 percent of energy to be generated from renewable sources by 2030.9Valerie Volcovici, “Latin America pledges 70% renewable energy, surpassing EU: Colombia minister,” Reuters, September 25, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-climate-change-un-colombia/latin-america-pledges-70-renewable-energy-surpassing-eu-colombia-minister-idUSKBN1WA26Y.

Guyana

Guyana is on the verge of a dramatic increase in energy production following one of the most prolific oil reserve finds in recent history and probable associated gas in the country’s offshore. For these reasons, Guyana is now a major destination for US investment. With a population of fewer than 800,000, this small nation expects to see its native oil production rise from zero to nearly 750,000 barrels per day by 2025.10US International Trade Administration, “Guyana—Oil and Gas,” July 9, 2019, https://www.export.gov/article?id=Guyana-Oil-and-Gas. The country’s government estimates that national income from the new oil and gas industry will accelerate from $300 million in 2020 to nearly $5 billion a year in 2025.11Kevin Crowley, “Guyana may not be ready for its pending oil riches, but ExxonMobil is,” World Oil, August 13, 2019, https://www.worldoil.com/news/2019/8/13/guyana-may-not-be-ready-for-its-pending-oil-riches-but-exxonmobil-is. By then, Guyana could see its gross domestic product (GDP) swell by 1,000 percent and boast the highest per capita wealth in the hemisphere.12“Latest oil finds suggest Guyana will become richest nation per capita in hemisphere,” The Caribbean Council, September 16, 2019, https://www.caribbean-council.org/latest-oil-finds-suggest-guyana-will-become-richest-nation-per-capita-in-hemisphere/.

With no prior experience in the management of energy development at this scale, Guyana’s priorities include assistance to establish a robust framework to ensure good governance and a safety protocol and regulation of the petroleum industry, receiving technical advice and assistance on how and whether to develop refining capacity, and guidance on how to leverage national income to create a long-term transition to renewable energy. Guyana will need particular support to integrate advanced oil and gas industry technologies (such as new artificial intelligence functions) into its upstream development and management, to learn how to leverage technology to complement emerging human capacity, and to enable the enforcement of robust standards of operation. Guyana also seeks to rapidly scale up the use of associated gas in the country’s energy mix, particularly as it aims to extend reliable power access and modernize its energy systems in line with an energy transition. Associated gas could potentially have numerous applications in the country’s energy system. Notably, existing power generation is at low levels, is dominated by high-emission diesel generation, and does not provide energy access to significant parts of the population that are not connected to the grid. As with other countries in the region, ensuring access to affordable and sustainable fuel sources is a high priority and critical to Guyana’s overarching energy security in spite of the country’s recent substantial oil discoveries.

In addition, Guyana seeks to use new income generated by oil production to modernize roads, bridges, ports, and other forms of transportation infrastructure. It is seeking support to build its national capacity to manage these tasks and advice on avoiding the numerous pitfalls other nations, including its own neighbors, have endured when faced with lucrative natural resource development. Guyana seeks to play a broader regional role as well, potentially supporting greater Caribbean energy integration and designing cross-border power and rail projects with Brazil.

Mexico

Mexico is a major US trading partner. The two nations enjoy significant trade in crude oil, petroleum products, natural gas, and (increasingly) electricity. Mexico’s national priorities include expanding energy access to the southern part of the country and expanding grid access in Baja California in the west. Long dependent on diesel and fuel oil, Mexico is meeting its national clean energy targets by transitioning to natural gas and increasing the share of renewable energy in its energy mix. Mexico plans to expand its domestic refining capacity. It continues to seek investments in electricity transmission and gas transportation, both of which are commissioned by special government corporations created as a result of the 2013 Mexico Energy Reform to facilitate greater regulatory transparency and independence, include external directors, and enhance competition.13These corporations include, for example, the National Energy Control Center (CENACE) and the National Center for

Natural Gas Control (CENAGAS) and a reformed Energy Regulatory Commission (CRE). See also: David L. Goldwyn, Neil R. Brown, and Megan Reilly Cayten, Mexico’s Energy Reform: Ready to Launch, Atlantic Council, 2014, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/MexEnRefReadytoLaunch_FINAL_8.25._1230pm_launch.pdf.

After undertaking a major transformation in its energy framework in a prior administration, Mexico will hopefully communicate early in 2020 its priorities for new investment. Clear signals to the investment community on the areas in which it seeks investment and the conditions for creating that investment will be a tremendous opportunity for Mexico. For now, the investment community, as well as the energy industries, sees contradictory and confusing signals as to the desirability of additional private investment in the oil and gas upstream in the fuel and power sectors. Volatility in the development of the pipeline system also heightens the level of risk for previously enthused investors. The government seeks to significantly increase oil and gas production as well as strengthen the capacity of Pemex, the national oil company. Nuclear energy has held high-level support in the past, but would need more concrete signals of support to encourage further industry development.14“Nuclear Power in Mexico,” World Nuclear Association, September 2017, https://www.world-nuclear.org/information-library/country-profiles/countries-g-n/mexico.aspx. Mexico has strong regional ambitions as well. It is interested in providing natural gas and electricity to Central America in support of greater economic prosperity and grid stability in that region. Mexico may also benefit from a concerted effort to increase cross-border pipeline infrastructure across the US-Mexico border, which would support Mexican industrial development and economic security and increase the availability of affordable natural gas supplies. Cross-border electricity interconnections between Mexico and the United States would also be beneficial to Mexico, especially as greater shares of renewable-based electricity generation will be integrated into its electricity mix.

V. A new US energy strategy for the Western Hemisphere

Given the shared desire to promote prosperity, energy security, democracy, and integration in the hemisphere, and the diverse needs of its friends and neighbors, the United States should consider a fresh approach to energy in the Americas that is comprehensive in nature and targeted in its approach. With its broad and diverse experience with energy development; its national interests in energy development in North America, South America, Central America, and the Caribbean; and its own experience in energy integration, the United States is a natural convener to create a new platform to further the development of hemispheric energy resources, expand energy access, and deepen energy integration.

From the broadest perspective, this strategy seeks to promote a common commitment to both energy security and sustainability, which prioritizes raising standards across the region. While there are subregional differences, our goal is a highly competitive energy community of the Americas, with cooperative and harmonized regulatory frameworks, the development of efficient and better integrated electricity and gas markets, diversified and resilient energy supplies, universal energy access and improved delivery systems, and sustainable resource research, development, and deployment. An effective, mutually beneficial strategy will recognize the heterogeneity among the key regions of Latin America (South America, Central America, and the Caribbean), particularly in terms of resources and respective needs, and tailor the US approach accordingly.

A new US energy strategy should be based on five core principles:

It should welcome all democratic nations that wish to partner with the United States on a bilateral basis or in collaboration with others (e.g., multilateral organizations and development banks) when appropriate to facilitate the development of energy resources and deepen regional integration.

It should create, strengthen, and complement existing platforms15Importantly, and for various reasons, this US-led strategy may be better suited to complementing some existing platforms more so than others and duplicative efforts should be avoided. The Energy and Climate Partnership of the Americas (ECPA), for example, may be particularly well suited to support or facilitate some meetings, platforms, and workshops within these focus areas. for all participating nations to enhance cooperation and share best practices, identify key targets for energy investment in the hemisphere and obstacles to that investment, and link private sector investors to investment opportunities across the energy value chain.

It should use the deep technical expertise of the DOE, its national laboratories, and its US government agency partners to foster fact-based informed conversations on critical issues and provide technical expertise.

It should measure its effectiveness by the following criteria: modernization of energy frameworks, cooperation in energy innovation, deployment of advanced energy technologies, increased levels of financing and sharing of best governance practices to facilitate closer interconnections among neighbors, increased prosperity in the hemisphere, and greater energy security.

It should adopt a whole-of-government approach. The leadership of the secretary of energy will be indispensable to focusing and optimizing the robust programs and efforts of the many other US departments and agencies already committed to promoting hemispheric energy development, as well as securing the support of relevant federal, state, and regional regulators.16By way of illustration, the Department of State supports the visits of foreign officials to the United States and the travel of US experts to host countries, and provides technical support in power sector development and energy governance. The US Agency for International Development (USAID) provides extensive support in power sector development. The Department of Commerce supports trade missions. The US government’s América Crece initiative seeks to overcome trade barriers and improve frameworks across the hemisphere. US trade and development finance agencies, the Export-Import Bank of the United States (EXIM), US International Development Finance Corporation (USIDFC), and the US Trade and Development Agency (USTDA) provide indispensable support in project development, risk insurance, and financial support. The Department of the Treasury can provide technical assistance and its role in international financial institutions can support a focused effort.

The strategy should be implemented through the following three core structural elements:

Leadership. The first building block in a new energy strategy should be the continued commitment of the secretary of energy to lead in this area and mobilize other US departments and agencies to support this effort.

Energy summit. This new energy strategy should be launched at an energy summit in 2020. All of the eligible regional energy ministers, leading regional state-owned enterprises, and energy sector investors should be invited to a conference focused on the key energy priorities of the hemisphere.

The summit, which could be convened on a biannual basis, should focus on enhancing regional investments, trade, and integration opportunities in the energy sector.

At its launch, the inaugural summit should consider a political declaration committing all of the nations to seek zero tariffs and support for free trade in energy commodities, electricity, and services, as well as a commitment to establish frameworks to provide a secure environment for investment, good faith resolution of disputes, greater common standards, and the implementation of best practices in procurement.

The DOE should strongly consider the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) and other development institutions as summit partners to leverage existing investment promotion and financing facilities and maximize private sector development. The summit could also be a complement to existing platforms and meetings already being convened on a regular basis through these other institutions.

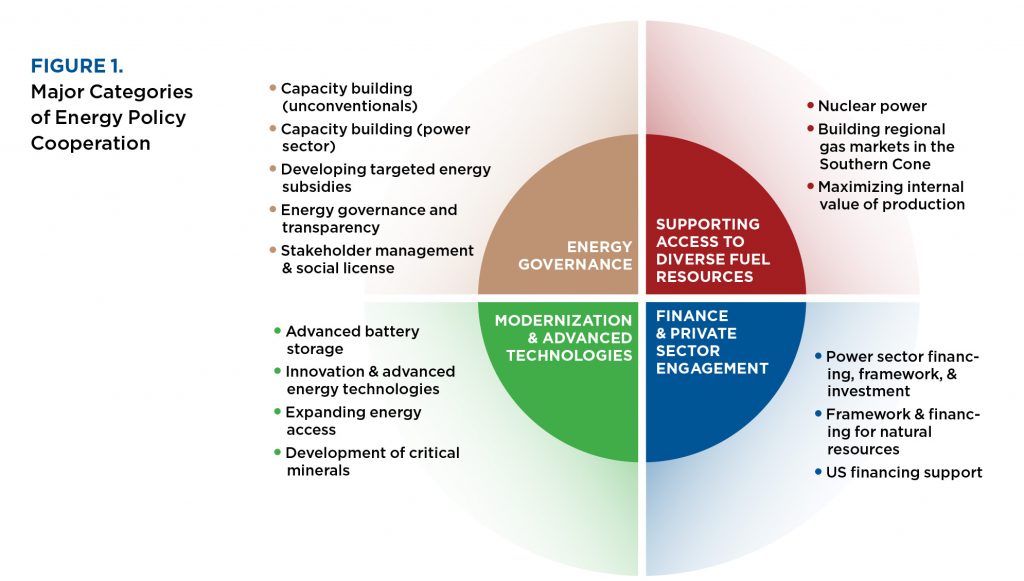

Regional cooperation forum. In addition to a summit, the DOE should organize multilateral and bilateral platforms for collaboration on the key issues of concern for hemispheric partners. These forums might take the form of multilateral meetings on issues of broad concern or tailored collaborations on areas of a narrower concern. Based on our consultations, and the work of the Atlantic Council in the hemisphere, we see fifteen immediate and urgent areas of collaboration. We list these in greater detail below. These areas of collaboration are grouped into four overarching themes: energy governance, supporting access to diverse fuel resources, finance and private sector engagement, and modernization and advanced technologies.

A. Energy governance

Capacity building: Unconventional fuels. Countries that are experienced in conventional oil and gas development now face major new challenges when beginning unconventional development, particularly in regulating air quality, water quality, and geologic concerns (specifically, seismicity). These issues have led to tensions in some countries over social license to operate (SLO) for unconventional development (especially hydraulic fracturing) and have made stakeholder management increasingly challenging. In other countries, notably Argentina, access to financing in support of unconventionals is limited. The DOE can gather US federal and state regulators and convene existing and prospective producers of unconventional energy (Argentina, Canada, Colombia, and Mexico) to share best technological, stakeholder management, and regulatory practices.

Capacity building: Power sector operation and regulation. Nations introducing significant levels of new energy resources, particularly variable renewables, face political and technical challenges in easing the burden of adjustment on existing generators. Energy regulators, even in developed economies, are challenged to design tariffs to provide fair rates of return for investors, reasonable prices for consumers, and high levels of reliability. For its part, the DOE can gather state-level regulators, the National Association of Regulatory Utility Commissioners (NARUC), regional transmission authorities, independent system operators, and electricity reliability experts to share knowledge, experience, and technical expertise on these issues. The US State Department, notably, has experience with convening regulatory workshops which bring overseas partners together with US Regional Transmission Organizations (RTOs) and Independent System Operators (ISOs). These experts can also share new information on best practices in system resiliency and cybersecurity.

Developing targeted energy subsidies. The question of energy subsidies, particularly for fossil fuel-based energy, is a serious and unresolved dilemma throughout Latin America that is at the crux of energy and economic development challenges. In the Americas, as in other parts of the world, recent efforts to reform pricing for energy (especially for end-use consumption, such as residential electricity) have resulted in unintended economic burdens that often disproportionately affect low-income groups. Energy prices and appropriate compensation (for a variety of fuel types and throughout their value chains) can be difficult to get right, but there is growing expertise, especially among the major international financial institutions, on how governments can achieve a proper and mutually beneficial balance. Reforming subsidy and pricing mechanisms merits its own workshop where the United States could convene international financial experts with private sector investors and partners to develop better paths forward for governments trying to better target subsidies and improve their fiscal frameworks. The DOE should also seek interagency partners with deep expertise in finance and commodity pricing to support this aspect of the strategy; the US Department of the Treasury, for example, is especially well-equipped to partner on this front.

Energy governance and transparency. Guyana is in a special category in needing to establish the capacity—human, technical, and otherwise—to regulate dramatically increased levels of production in a short period of time. It is receiving advice from the IDB, the US government, and other sources. Many countries in the hemisphere face similar challenges with revenue management, adapting framework terms to changing conditions, and building capacity. The DOE could convene a unique peer-to-peer workshop (with the first time directly led by the United States), including development partners and other agencies, to share best practices and build on previous preparatory work done by international financial institutions and nongovernmental organizations.

Stakeholder management and social license. Many nations, including Brazil, Canada, Colombia, and the United States, are facing challenges siting new infrastructure, from pipelines and power plants to infrastructure in support of exploration and production. Governments and companies are all striving to learn better ways to conduct stakeholder engagement, especially with indigenous communities. The DOE should convene all interested countries, companies, and community engagement experts to understand common challenges, best practices, and new approaches. Other multilateral fora already engaged on this aspect of resource development, such as the IDB, would be excellent partners in this aspect of the strategy.

B. Supporting access to diverse fuel resources

Nuclear power. Argentina, Brazil, and Canada all seek to expand the use of nuclear power and advance the use of next generation and emerging nuclear technologies. Mexico has lately signaled a willingness to expand capacity at the Laguna Verde Nuclear Power Plant, its sole nuclear power generation facility, which is located on the coast of the Gulf of Mexico. The United States, likewise, has a national interest in sustaining a civil nuclear industry. Nations seeking to diversify their energy mix have an interest in learning about access to small modular and other appropriately sized reactors. The DOE, led by its Office of Nuclear Energy and its national laboratories, could convene national nuclear regulators, technology providers, and experts to harmonize safety rules, establish trade standards, and devise strategies to advance the deployment of new generations of nuclear reactors.

Building regional gas markets in the Southern Cone. In the Southern Cone of South America, Argentina and Brazil are both major gas producers and consumers. Brazil, in particular, relies on natural gas to balance hydropower, which can vary in its adequacy on a seasonal basis and depending on the weather. All of these nations—including Chile, as mentioned above—can often benefit from selling surplus energy to each other. The region has an uneven history in natural gas and electricity trade and no common rules for regional energy markets. The DOE could convene regional producers in the Southern Cone and LNG operators to address ways to aggregate markets and harmonize trading rules.

Maximizing internal value of production. One key component of developing resilient, well-resourced energy markets is having sufficient, reliable, and predictable demand for fuels. Growing markets with clear demand needs are lower risk and more easily investable. Latin America is, in many respects, an industrializing region. Its future economic growth may hinge on industry and manufacturing. Support for industrial development in the region, especially through the creation of aggregate demand via high-priority energy corridors (e.g., among Mexico and the Central American nations), will support economies of scale for fuel and electricity demand. Support for industrial development thus produces a virtuous circle resulting in greater supply and energy security. This particular area is ripe for whole-of-government and interagency engagement, as the DOE can partner with the State Department, the US Department of Commerce, the US International Development Finance Corporation (IDFC) , and others to support industrial development in the region.

C. Finance and private sector engagement

Power sector financing, framework, and investment. As the world’s nations grapple with the dual challenge of meeting energy security while protecting the environment, the dominant trend is towards greater electrification. In each of the six nations we consulted, we heard of the need for investment in power generation and transmission, advice and capacity building related to grid stability and the integration of renewables, and pricing and incentivizing reliability to support the anticipated growth in demand for energy through power. One key piece of this puzzle for Latin America is developing proper regulatory frameworks that will undergird modern, high-capacity power grid infrastructure. Similarly, promoting investment in the power sector can be challenging in several respects. First, national and local power grids are often regulated by the government. Rates of return are fixed and can be in the range of 3 to 7 percent, compared to 15 percent return on investment for the hydrocarbon sector. Unlike other natural resources, which can be sold at low prices into global markets, electricity depends on creditworthy purchasers who must sign power purchase agreements (PPAs) with generators in order to attract project financing. Transmission tends to be expensive, provide a fixed rate of return, and is most often commissioned by the government. In places where electricity prices are subsidized, or there are high levels of non-transmission losses, transmission systems can be inadequate or be in high degrees of disrepair. This can be a major impediment to securing investment in new power generation. For this reason, most nations need advice and assistance in designing frameworks that will be attractive to investors. The DOE might convene electricity experts, utility professionals, investors, and interested nations to review key legal and regulatory factors for attracting power sector investment. The DOE can likewise convene regulators, utilities, and investors to discuss how to set electricity tariffs, how to prepare PPAs that meet investment standards, and ways to design auctions to attract investors who will provide competitive prices to consumers. Likewise, in light of the considerable breadth of experience with successful auctions now present in the region, there is an opportunity for cooperation among all participants and sharing of lessons learned.

Framework and financing for natural resources. The most common concern in the hemisphere, from the Southern Cone to the Caribbean, is the need to attract financing for natural resource development and adjacent infrastructure—particularly where resource development connects to power systems. Some nations, particularly in the Caribbean and Central America, have weak credit positions and face significant competition for investment. Other nations have historical experiences where they have interrupted supplies to neighboring nations during times of national crisis, or imposed capital controls or new levels of taxation. Private sector participants attest that the key factor in making investment decisions and pricing risk in a given country is the legal and fiscal framework. The DOE can convene investors, countries, development institutions, and risk insurers to have a guided conversation on creating competitive frameworks. Several countries in the hemisphere are focused on using private capital to finance the expansion of oil and gas transportation. These projects can be challenging to finance, depending on the host country’s market structure and the legal framework for siting and obtaining environmental permits for pipelines. The DOE might convene a meeting, in part utilizing the new National Petroleum Council report on energy transportation infrastructure, to address these challenges. Stakeholders would include interested countries, pipeline and other investors, relevant federal and state-level regulators, and risk insurers.17“Dynamic Delivery America’s Evolving Oil and Natural Gas Transportation Infrastructure,” National Petroleum Council, 2019, https://dynamicdelivery.npc.org.

US financing support. The United States has many tools with which it can support energy development in the hemisphere. As the United States ramps up its support, it can be helpful to enhance awareness among investors and host countries about the full suite of US government tools that can be brought to bear, and about how investors and countries can access these tools. A financing workshop could, in particular, describe and clarify categories of support and any conditions attached to US government support for regional partners. The US International Development Finance Corporation (IDFC) , the US Trade and Development Agency (USTDA), and the Export-Import Bank of the United States (EXIM) can bring their expertise and resources to bear in support of financing opportunities.

D. Modernization and advanced technologies

Advanced battery storage. Many Latin American countries experience high seasonal variations in power and natural gas consumption that complicate the economics of natural gas and power supply. The region has highly limited underground gas storage options. Multiple nations want advice on siting, pricing, and financing both gas and power storage. Moreover, battery storage (chemical, hydrogen fuel cell, and other types) is seeing rapid technological advancements and cost reductions elsewhere in the world. Many Latin American countries with significant dispersed rural populations could benefit tremendously from access to these new forms of battery storage. The DOE can convene technology providers, storage experts, gas developers, and national regulators to review effective models to incentivize energy storage. Other US government agencies, including the USTDA, may also be well positioned to support pilot programs to test these in Latin American contexts. EXIM and the IDFC can provide valuable financing support for emerging technology and potentially higher-risk storage projects.

Innovation and advanced energy technologies. The Americas are already a locus of technological innovation in energy beyond battery storage solutions. The reliable and sustainable energy systems of the future, in the Americas and worldwide, will demand innovative solutions throughout midstream and end use infrastructure—some of which are only just emerging or in the earliest stages of scalability. Latin America offers unique opportunities to test new and emerging technologies, especially in power generation and grids. Off-grid and mini-grid options are ideal for rural and island communities, and the rapid uptake of electric vehicles (a priority in multiple Latin American countries’ emissions reduction plans) is an opportunity to study vehicle-to-grid as a new decentralized energy storage option. Another area of rapid innovation is in hydrogen, not only as a storage solution, but potentially as a vehicle and generation fuel with similar advantages as natural gas (and conveniently suited to existing pipeline infrastructure). The development of new biofuels (e.g., algae), low and zero-carbon fuel resources (e.g., renewable gas), and the toolsets necessary to scale and maintain energy systems that use them are all areas where US leadership and ability to garner private sector engagement and resources can be both constructive and transformative; for example, countries and companies can share the key elements that create an innovation friendly culture, from regulatory flexibility to competition policy.

Expanding energy access. Even developed nations face the challenge of providing energy access to remote areas. In some cases, there is a need to provide electricity to residential populations. In other cases, especially in Brazil and Colombia, there are opportunities for mineral development that can only be economically viable if there is also access to electricity. The DOE can lead a conversation with development experts, distributed energy experts, and regulators to focus on the best learning on the use of distributed energy systems, from mini-grids to gas and battery-powered combinations.18The Atlantic Council’s Global Energy Center (GEC) has done extensive on-the-ground research focused on resiliency and adaptation in Puerto Rico in the wake of recent devastating hurricanes that impacted the US territory’s grid system. See: Joe Bryan, “The time is right for energy transformation in Puerto Rico,” EnergySource, January 16, 2019, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/energysource/the-time-is-right-for-energy-transformation-in-puerto-rico/.

Development of critical minerals. In a world that is rapidly electrifying, critical minerals are of great and accelerating importance. The sourcing, separation, and processing of these minerals raises challenging geographic, environmental, and geopolitical questions. Substantial deposits of gold, copper, lithium, manganese, bauxite, phosphates, and other critical minerals are found throughout Latin America; indeed, the US Geological Survey has partnered on cooperative mineral development projects throughout the region, including in Argentina, Bolivia, Colombia, Costa Rica, and Uruguay.19Michael S. Baker, Spencer D. Buteyn, Philip A. Freeman, Michael H. Trippi, and Loyd M. Trimmer III, Compilation of geospatial data for the mineral industries and related infrastructure of Latin America and the Caribbean: Open-File Report 2017–1079, US Geological Survey, US Department of the Interior, and Inter-American Development Bank, https://doi.org/10.3133/ofr20171079. Canada represents one of the most secure and resilient sources of minerals and metals imports to the United States and is currently an important supplier of thirteen of the thirty-five minerals20These include: antimony, barite, bismuth, cesium, cobalt, graphite, indium, lithium, niobium, platinum group metals, potash, tellurium, and uranium. “Annual Statistics of Mineral Production,” Natural Resources Canada, accessed February 6, 2020, https://sead.nrcan-rncan.gc.ca/prod-prod/ann-ann-eng.aspx. deemed critical by the United States, with the potential to supply many more. Canada and the United States are already working to strengthen regional critical mineral supply chains through the US-Canada Critical Minerals Action Plan, which was finalized in December 2019 by US President Donald J. Trump and Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.21United States and Canada Finalize Action Plan on Critical Minerals Cooperation, US Department of State, press release, January 9, 2020, https://www.state.gov/united-states-and-canada-finalize-action-plan-on-critical-minerals-cooperation/. Lithium, abundant throughout the Americas, is in extremely high and growing demand worldwide for its applications in battery storage, and demand is expected to grow further on the back of accelerating vehicle electrification.

Utilizing these raw minerals introduces difficult questions, particularly around management of local stakeholder engagement and promoting safe, sustainable development. Some countries in the hemisphere, such as Chile, are already experienced mineral producers. This is an area where the DOE and the Departments of State and the Interior can offer technical and regulatory assistance on starting or expanding development for interested countries, and where regional partners may be able to assist one another. The State Department has taken leadership on this front through the recently developed Energy Resource Governance Initiative (ERGI), which Canada joined in late 2019.22Energy Resource Governance Initiative, US Department of State, June 11, 2019, https://www.state.gov/energy-resource-governance-initiative/. Outside of ongoing efforts at State, there may be other opportunities for the DOE to work with like-minded partners in the region to accelerate development, production, and commercialization of technologies to increase downstream value-add processing.

VI. Conclusion

There are multiple imperative energy security needs throughout the Americas where the DOE is well-positioned to support regional partners, convene partner countries to share learnings and models, and enhance US political and security objectives. The United States has a number of important tools at its disposal and a wealth of knowledge, expertise, and resources that can be brought to bear through the interagency process in support of an overarching hemispheric strategy.

There are significant, diverse needs throughout the region, including improving the mining and production of critical materials and discovering novel ways for oil and gas exploration. Our close examination of six key countries, however, revealed important areas of overlap—notably on conventional and unconventional development, governance and standards, finance and investment, and management of new and sustainable energy resources. Leadership from the DOE on these fronts will come not a moment too soon for Latin America.

About the author

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Andrea Clabough of Goldwyn Global Strategies, LLC for her extensive and outstanding research and editorial support.

The author would also like to acknowledge Reed Blakemore and Felipe Zarama Salazar for their efforts in spearheading this project, and in particular their facilitation of the many consultations that guided the findings of this report.

Special recognition to Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center Director Jason Marczak and Global Energy Center Director and Richard Morningstar Chair for Global Energy Security Randolph Bell for their guidance and leadership.

The author is also grateful to Jennifer Gordon and Becca Hunziker for their editorial support.

Learn more

Subscribe to the Latin America Center newsletter

Sign up for the Latin America Center newsletter to stay up to date on the center’s work.

Image: The Western Hemisphere at night in 2016, compiled using the Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership’s (Suomi-NPP) Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) data from NASA Goddard Space Flight Center’s Miguel Román. NASA Earth Observatory/Joshua Stevens