A rising nuclear double-threat in East Asia: Insights from our Guardian Tiger I and II tabletop exercises

Click on the banner above to explore the Tiger Project.

Guardian Tiger led me to realize that we need to rethink our operational and strategic Indo-Pacific posture. We have to be ready for a local fight to become a regional war with nuclear escalation and threats to the homeland. It’s scary, but we can’t assume it away. We could face China and North Korea simultaneously. Either of them could go nuclear before giving up.

—US government official, participant in the Guardian Tiger tabletop exercises, name withheld

A decade from now, the United States is very likely to face operational and strategic challenges in the Indo-Pacific even more complex and difficult than those it faces today. The nuclear capabilities of China and North Korea are growing rapidly, and the risk is increasing that a conflict with one would escalate horizontally to a regional conflict involving both.

By 2030, China will likely be a near peer to the United States in terms of strategic nuclear capabilities. Its amphibious, air, and strike capabilities could also dramatically improve its ability to project force to Taiwan and the surrounding region. China’s plans, intentions, and timeline for use of force against Taiwan remain topics of heated debate. However, in the next five to ten years, it is plausible that Beijing will consider conditions to be more favorable for a military resolution, even if it is not eager for a global war with the United States.

In this same period, North Korea is likely to field a wider range of more precise and effective nonnuclear escalatory options, as well as a robust, mobile, tactical nuclear-missile force—backed by a far more credible capability to retaliate against the region and the continental United States with thermonuclear weapons. These capabilities will provide Pyongyang with its own reasons to consider escalating its use of force against South Korea, though its aims will likely be far more limited than Beijing’s aims for Taiwan.

By 2030, it is unlikely that Beijing and Pyongyang will have developed enough trust to enable them to coordinate a campaign of aggression to achieve their goals. However, their individual interests and their common animosity toward the United States and its allies will give each of these potential US adversaries strong incentives to escalate—opportunistically or reactively—in the event the other initiates a conflict. In 2030, each of these potential adversaries will also have much stronger incentives and capabilities to threaten or conduct a limited nuclear attack in the event that either adversary initiates such a conflict.

Meanwhile, two key US allies in the Indo-Pacific—South Korea and Japan—are investing to develop far more powerful militaries by 2030. These allies’ military capabilities, as well as their diplomatic, informational, and economic influence, could help counter and deter growing threats. However, these allies will also have greater motivation and capability to act unilaterally if their own interests are threatened.

Considering these trends, US military and government leaders will face some tough challenges in the Indo-Pacific a decade from now. With these in mind, the Indo-Pacific Security Initiative (IPSI)—with the support of the Strategic Trends Research Initiative of the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA)—launched the Guardian Tiger tabletop exercise series to help prepare mid-level US government and military leaders for future key roles in addressing such threats. These initial Guardian Tiger exercises were also intended to develop analytic insights and actionable recommendations to help the United States start preparing for limited nuclear attacks by an adversary—work that is continuing today. This report summarizes and analyzes the first two Guardian Tiger exercises.

Key findings

- If the United States is engaged in conflict with either China or North Korea, it might not be able to deter the other adversary from escalating that conflict or initiating a separate one. As a conflict with an initial adversary escalates, it may become necessary—and even strategically or operationally advantageous—to accept the risk of such simultaneous conflicts against multiple adversaries rather than remain hamstrung by the costs.

- What it takes to prevent North Korea from escalating a conflict will differ significantly from what is required to prevent China from doing so. Credible threats of vertical escalation from Pyongyang, particularly threats of nuclear strikes, are likely to come early and often. Meanwhile, China has many strong incentives and non-nuclear options to escalate horizontally—across domains and geography, including in space, in the cyber domain, and against the US homeland—to disrupt Washington’s will and ability to support Taiwan. Each adversary’s distinct escalation pattern will require a tailored set of capabilities and approaches to anticipate, deter, and counter it.

- War in the Indo-Pacific may start over one flashpoint, but it will quickly become about much more. A war beginning over Taiwan is likely to become about far more than the status of Taiwan itself, including China’s overall regional and global position post-war, as well as the US homeland’s safety. Meanwhile, an escalating South Korea-US conflict with North Korea will likely become about the future of the global nuclear order, the credibility of US extended deterrence, and the potential unification of the long-divided Korean peninsula—not just about restoring the armistice.

- The United States should prepare for the possibility of a limited nuclear attack—with responses beyond just the threat of complete annihilation. The political and military choices necessary to better prepare for a limited nuclear strike, and to operate effectively in the aftermath, are hard. The tendency to avoid these hard choices may mean that the United States is left with no good conventional options if threats of disproportionate punishment fail to deter a limited nuclear attack. Meanwhile, US low-yield nuclear response capabilities are limited, potentially leaving only ineffective or excessive nuclear options in some circumstances.

- Effective deterrence of war and of escalation during war in the Indo-Pacific will require the United States to simultaneously coordinate laterally and at multiple echelons, including prior to the outbreak of conflict. This would involve establishing stronger combined (multinational), joint (cross-military service), and interagency command and control, coordination, informational shaping, and planning mechanisms between the United States and its allies across multiple military commands and government agencies, in advance of a crisis.

Methodology

Each of the first two Guardian Tiger tabletop exercises presented participants with a distinct scenario set in the year 2030, featuring conditions likely to lead to simultaneous confrontations involving the Korean peninsula and the risk of limited nuclear use.

The scenario for the first exercise, Guardian Tiger I, was premised on North Korea initiating a limited conflict that escalated to chemical weapons use and included potential drivers for China’s involvement. The scenario for the second exercise, Guardian Tiger II, was based on a conflict initiated by Chinese aggression against Taiwan, with the potential for that conflict to spill over into Korea through several potential pathways.

Although not truly “free play” with unlimited scope for changes, the exercises were designed to allow for a considerable degree of latitude for participants—within the bounds of plausibility and some general guidance from facilitators playing the roles of national leaders. The North Korea cells during each exercise, in particular, chose actions that had not been anticipated during the design phase. This required the facilitation team to adjust the pathways for the development of the scenarios for the exercise.

The more than sixty participants included US government officials, military officers, and leading nongovernment experts. Participants were organized into a US (blue) team and a control team. The blue team consisted of three cells of up to a dozen members each, representing different echelons: a national interagency cell (approximating National Security Council mechanisms), a national defense and military cell (addressing considerations for the Office of the Secretary of Defense, the joint staff, and relevant joint combatant commands), and a cell representing the US military based in the Korean theater. The control team included the exercise project staff, as well as smaller cells that simulated North Korean and Chinese senior leadership and represented allies that varied in each of the two scenarios.

Analysis: Two roads to war

The following sections summarize the starting conditions and flow of events for Guardian Tiger I and II. Note that these scenarios took place based on a set of assumed, projected conditions for the year 2030 and explicitly excluded direct Russian involvement, based on the rapidly changing North Korea-Russia relationship at the time they were designed.

One road to war: North Korea launches a limited attack on South Korea

The road to war leading to the conflict scenario for the first Guardian Tiger tabletop exercise is depicted in Figure 1. It began with North Korea conducting a limited attack on South Korean military forces that did not include any nuclear, chemical or biological weapons. Submarine and missile attacks targeted South Korean vessels and aircraft in the Yellow Sea (known in South Korea as the West Sea), while North Korea launched precision missiles and rockets at South Korean marine bases in South Korea’s Northwest Islands. North Korea claimed that its actions were in response to South Korea’s violations of North Korean sovereignty, but the US Intelligence Community identified “time pressure” due to factors such as the growing South Korean and US capabilities and domestic political pressures as a major driver for Kim Jong-Un’s attack calculus.

South Korea responded unilaterally with counterstrikes on a range of North Korean military targets. North Korea then escalated further with chemical weapons strikes against two South Korean military facilities. Pyongyang warned that it would respond to US intervention or a US threat to its leadership or nuclear forces with nuclear escalation, in accordance with its September 2022 “Law and Policy” on nuclear weapons. Upon South Korea’s request for US support, the South Korea-US military committee—including each country’s Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff acting on orders from their respective Presidents—agreed that Combined Forces Command (CFC) should decisively defeat North Korea’s attack while deterring North Korean nuclear employment and Chinese military intervention. Beijing called for a ceasefire and withdrawal of forces from the conflict zone, while preparing its own military intervention.

Figure 1. Guardian Tiger I road to war: Visual summary

Timeline A: Turn one

In the first turn (Timeline A), South Korea focused on working in concert with the United States while signaling readiness for unilateral action if necessary. South Korea reached out to the United States to request military support and public messages to reinforce Washington’s extended deterrence commitment.

Washington agreed to strengthen its cooperation with South Korea, and CFC successfully conducted a bilateral strike on the North Korean chemical weapons site. The United States initiated a limited force flow into the theater, careful to avoid triggering further escalation, and offered intelligence support to South Korea and other regional allies in addition to preparing offensive and defensive cyber operations. The US approach focused heavily on diplomacy, including presidential engagement to reassure South Korea and Japan, as well as broader diplomacy condemning North Korea’s violation of South Korea’s sovereignty. Efforts to persuade China to assist in applying extreme pressure on North Korea, particularly through an energy cutoff, fell flat. The overall flow of the first day of Guardian Tiger I is depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Guardian Tiger I, turns 1–3 (Timeline A)

Timeline A: Turn two

At the start of the second turn, North Korea ramped up its nuclear threats—including warning of a pre-delegation order for tactical nuclear employment and conducting a missile demonstration off South Korea’s west coast—while continuing to conduct limited attacks along the demilitarized zone (DMZ) with special operations forces (SOF) units and artillery. China began a limited intervention into North Korea with Pyongyang’s permission, deploying ground, naval, air, and air-defense assets in and around North Korea to constrain US-South Korea operations.

In spite of Chinese warnings against further US intervention, South Korea and the United States activated a combined counter-fire task force under CFC. Washington warned against any nuclear use and condemned North Korean nuclear threats, while emphasizing that active Chinese engagement in the conflict would result in serious economic, diplomatic, and military consequences. South Korea reacted to the increasing tension with concern and was particularly worried by Washington’s risk aversion and restraint. Unable to rely on US protection of its interests, South Korea executed a unilateral strike with sea-based missiles against the site of the North Korean missile demonstration launch and conducted precision artillery/multiple-launch rocket system (MLRS) strikes on a North Korean divisional headquarters. South Korea also requested US assistance in monitoring North Korean launch sites to prepare to conduct preemptive strikes if necessary.

Timeline A: Turn three

In the third turn, North Korea escalated to a low-yield tactical nuclear demonstration, ostensibly targeted against a South Korean Navy destroyer in the Sea of Japan (referred to as the East Sea in Korea), while firing non-nuclear—but nuclear-capable—intermediate-range ballistic missiles (IRBMs) over Japan. North Korean representatives privately reassured Beijing that Pyongyang’s intention was to refrain from further escalating the situation unless it was warranted. China urged de-escalation by all parties.

The blue team cells debated response options to this nuclear use, but no consensus emerged. The National Interagency cell suggested that both nuclear and non-nuclear options be presented to the president, but with the emphasis on non-nuclear options. The national defense and military cell proposed a “pulsed operation” against North Korea with advanced precision-strike assets, while assuring China and North Korea that Washington did not want to use nuclear weapons or end the Kim regime unless North Korea used nuclear weapons again. The US theater military cell proposed nuclear and conventional responses, such as a combined nuclear-conventional general offensive or a nuclear strike near Pyongyang. This timeline ended without adjudication of final results.

Timeline B: Turn one

To explore a different pathway of how the options available to the United States could be affected by a different command and control structure, Guardian Tiger I included an alternative scenario with a key change in how US forces in the region were commanded and controlled via the notional creation of a new US Northeast Asia Command (NEACOM), a four-star joint warfighting command falling under US Indo-Pacific Command (INDOPACOM).1The starting conditions of Timeline B include a South Korean commander for CFC and a new Northeast Asia Command (NEACOM) over US Forces Korea (USFK) and US Forces Japan (USFJ), as a new four-star joint sub-unified command of US Indo-Pacific Command (USINDOPACOM). The events of Timeline A’s second turn mark the beginning of Timeline B, so that in the first turn of Timeline B, China had already intervened and North Korea had warned of delegation of authorities for North Korean tactical nuclear weapons employment. With NEACOM providing different options to the United States, and with more time to consider the possibilities, the blue team took a different approach. The United States supported South Korea-US CFC counterfire operations and South Korea’s interdiction of North Korean threats to its Northwest Islands with targeting intelligence support and with standoff fires coordinated by NEACOM under the direction of and with the support of INDOPACOM. With NEACOM leading the planning, US and South Korean forces also prepared for a pulsed conventional strike to be executed by CFC, with NEACOM in support, against a wide range of North Korean strategic and operational targets.2For more information on “pulsed” strikes, see “Air Force Future Operating Concept Executive Summary,” US Air Force, March 6, 2023, https://www.af.mil/Portals/1/documents/2023SAF/Air_Force_Future_Operating_Concept_EXSUM_FINAL.pdf.This pulsed conventional strike was to be ready for execution on short notice if North Korea escalated further. Meanwhile, the secretary of defense traveled to Seoul and Tokyo to underscore alliance resolve.

At this time, the United States was also concerned about the implications of North Korean officals other than Kim Jong Un potentially having the authority to use nuclear weapons, given the warning from Pyongyang that there had been pre-delegation of release authority to unspecified North Korean commands. With this in mind, the United States undertook a technical operation to send messages via North Korea’s cell-phone system to North Korean elites that they would be held personally responsible for any nuclear use and should oppose it. Though the messages went to many elites, the North Korean regime quickly deactivated the cell-phone network. This quick-turn effort had unclear results and credibility because North Korean elites’ perceptions had not been shaped by an information campaign over time, while the deactivation of the cell-phone network could have proven an impediment to future US information operations even while it disrupted North Korean domestic activities.

Timeline B: Turn two

In the second turn of Timeline B, China deployed additional air and naval assets into North Korean territory. China conducted cyberattacks against South Korea and the United States but did not engage in combat with South Korean, US, or North Korean forces. Suffering military setbacks, North Korea chose to make good on its threats of tactical nuclear strikes by conducting a low-yield nuclear ballistic missile attack against the South Korea-US naval base at Chinhae on South Korea’s southeast coast. North Korea did not warn China beforehand and expected the presence of Chinese forces and assets to restrain US retaliation, thereby limiting the US counterattack to conventional means. The ostensible delegation of authority was more for strategic communications purposes, as the strike was directed and approved by the North Korean leader, but US leadership did not receive confirmation of that—adding an additional element of uncertainty into the blue team’s deliberations.

In response, US and South Korean forces executed a pulsed conventional strike against key high-value targets, but did not expect this to bring an end to the regime. The intensity, speed, extent, and effectiveness of the response surprised North Korean leadership, but Pyongyang considered the heavy damage sustained an acceptable cost given the stakes. Ultimately, despite exploration of several potential military options to continue the conflict, the United States and South Korea did not remain fixed on ousting the Kim regime by military force in the near term, and instead began negotiations to end the conflict with North Korea and avoid a war with China.

A second road to war: China attempts to seize Taiwan by force

The road to war for the second exercise, Guardian Tiger II, is summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Guardian Tiger II road to war: Visual summary

The conflict in the scenario resulted from a Chinese ultimatum to Taipei, followed by an attempt to seize Taiwan by force. China’s multi-domain assault on Taiwan saw preparatory waves of joint fires and strikes on key control nodes, followed by multiple amphibious and airborne landings along Taiwan’s west coast. China’s ground and air campaign was accompanied by the imposition of a maritime exclusion zone (MEZ) and a near-total blockade around Taiwan to sever lines of communication through maritime and air interdiction operations. Finally, China initiated non-destructive cyberspace and space attacks against US regional military networks and satellites. Beijing also attempted to sway US allies to avoid becoming involved in the conflict, with mixed results. Seoul publicly condemned China’s aggression but refused to support Taiwan militarily or allow direct involvement of US Forces Korea (USFK) in the conflict. Beijing also dissuaded Manila from hosting additional US forces.

North Korea initiated a strategic messaging campaign that blamed Washington for starting the Taiwan conflict and attempted to split the South Korea-US alliance. North Korea warned South Korea against allowing itself to be dragged into a war by USFK, calling for Seoul to eject USFK. It also began transitioning to a semi-wartime state.

Turn one

All four turns of Guardian Tiger II are visually depicted in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Guardian Tiger II: Timeline summary

Turn one of Guardian Tiger II began with the faltering of China’s amphibious assault on Taiwan, driven by unexpectedly strong Taiwanese resistance and effective US strikes, which slowed offensive momentum. Only one amphibious Chinese lodgment was successful, with invasion forces suffering heavy losses and unsustainable munitions expenditures. This increased China’s incentives to escalate to maintain offensive momentum. Intense fighting continued between China and the US-led coalition, with heavy losses and munitions expenditures, which led the United States to consider pulling from USFK munitions stocks in South Korea.

Regionally, China conducted missile strikes against US airbases in Okinawa and western Japan, expanding the conflict horizontally in a bid to disrupt US combat power generation and reestablish offensive momentum against Taiwan. China declared an additional MEZ within the Yellow Sea, and threatened strikes against USFK bases unless South Korea restrained USFK involvement. China’s deterrence efforts against South Korea were successful, with USFK involvement and support to Taiwan ultimately constrained by mutual agreement between Seoul and Washington. North Korea also intensified its coercion attempts to eject USFK from South Korea, adding credibility to its threats by elevating military readiness posture to unprecedented levels.

The United States continued the flow of forces into the Taiwan theater and sought to halt China’s offensive momentum through standoff strikes. USFK leaders issued clear signals that USFK elements were not involved in the Taiwan conflict, in an effort to manage the threat of Chinese horizontal escalation.

South Korea prioritized deterring North Korea, and South Korean forces moved to maximum readiness posture short of war. CFC was activated, with some South Korean and USFK forces subordinated to it, and Republic of Korea Strategic Command (ROKSTRATCOM) was activated with key assets placed in readiness to deter further North Korean aggression. South Korea publicly and privately reiterated its expectation that USFK would remain focused on deterring North Korea, and that USFK munitions would not be pulled out for use in the Taiwan conflict. Japan conducted counterstrikes against Chinese forces launching missile strikes on US bases in Japan, which temporarily disrupted the Chinese strike campaign against Japan and fulfilled domestic expectations. Japan expanded its support to US operations, providing additional basing, munitions, logistics, and intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) support.

Turn two

Turn two began with Chinese missile strikes overflying North Korean and South Korean airspace, successfully striking key US bases in mainland Japan. Beijing provided only Pyongyang advance notification of the overflight. China’s overflight strikes were motivated by practical concerns. Its more numerous and evasive short-range ballistic missiles (SRBMs), which are capable of overcoming missile defenses more effectively, can only strike many USFJ facilities when fired from northern China and passing over the Korean Peninsula, not from eastern and southern China. China postured assets for intervention in the vicinity of the Chinese-North Korean border and initiated key intelligence sharing with North Korea. Finally, Chinese cyber actors intensified attacks against regional military and civilian targets.

North Korea conducted a limited provocation campaign against South Korea, with the ultimate goal of coercing the removal of USFK from South Korea. North Korea conducted an SRBM demonstration launch into the Sea of Japan (known in South Korea as the East Sea) in an attempt to decouple US nuclear extended deterrence commitments from South Korea and create space for further demands. North Korea also initiated a unilateral regional campaign of cyberattacks against military networks in South Korea. Washington restated its nuclear declaratory policy in an effort to deter North Korean nuclear use. The North Korea cell perceived this as hollow bluster that proved to be more destabilizing than stabilizing.

US forces continued combat operations around Taiwan, with Washington authorizing direct attacks on the remaining lodgment. These efforts halted China’s offensive momentum. Washington authorized proportional cyberattacks on both North Korea and China. US F-35 fighters, including dual-capable (i.e. capable of carrying nuclear bombs) aircraft, were deployed across Japan; after-action reports from both the China and North Korea cells indicated this was a critical concern. Washington attempted to limit escalation by refraining from striking Chinese mainland forces. Notably, the China cell perceived US hesitancy to strike the Chinese mainland as indicative of the success of its robust nuclear deterrent.

South Korea invoked the mutual defense treaty with the United States to request immediate, full-scale military assistance, initiated a partial military mobilization, and activated ROKSTRATCOM assets. It conducted proportional cyber countermeasures against North Korea, which resulted in the shutdown of North Korean cyber connectivity to the outside world and some degradation of North Korean offensive cyber capabilities. This shutdown challenged the efficacy of South Korean information operations later in the exercise, illustrating the value of functioning communication channels. Japan expanded US basing, enabling the dispersal of F-35s and underscoring the bilateral coordination needed to enable their deterrent effect. Japan also initiated additional economic sanctions against China, while contributing additional forces to counterattacking Chinese forces on and around Taiwan.

Turn three

Turn three began with China’s threat of nuclear use to force a resolution to the Taiwan conflict, backed by credible increases to nuclear posture. China conducted additional strikes against mainland Japan, targeting Japanese capabilities critical to conducting strikes and defending against additional strikes. China shifted targeting strategy against Taiwan toward national infrastructure in an unsuccessful attempt to decrease national morale. Chinese cyber actors intensified offensive cyber operations, focusing on regional airports and seaports to interfere with US and allied force flows.

After initial hesitation, North Korea was emboldened to take much stronger action by the escalation of the conflict between China and the US-led coalition, and by the establishment of a China-North Korea military coordination center. As a result, North Korea escalated. It conducted SRBM strikes and SOF attacks using small unmanned aircraft systems against key USFK facilities. It also executed simultaneous SRBM and underground nuclear tests to reinforce its nuclear deterrent and test US extended deterrence commitments to South Korea.

US forces conducted standoff strikes against North Korean maritime and air infiltration platforms that enabled previous North Korean SOF strikes, degrading North Korea’s capacity to conduct follow-on attacks. Additionally, US forces struck North Korean missile delivery platforms, and increased intrusive ISR in order to find and track dispersed ground-based missile delivery platforms. In response to the shootdown of its ISR aircraft by China, South Korea led CFC US-South Korea air operations within China’s Yellow Sea MEZ, which resulted in US-South Korea fighter engagements with Chinese aircraft. South Korea executed additional retaliatory standoff strikes against North Korean SOF bases that facilitated previous attacks, degrading North Korea’s capacity to initiate further asymmetric attacks. Japan shifted ISR and ballistic missile defense assets to combat the threat of North Korean missile strikes, and additionally heightened cyber defenses, improving its defensive posture and ability to respond to further escalation.

Turn four

Turn four began with China’s increase in nuclear posture and its launch of a fractional orbit bombardment munition (presumably nuclear) into a polar orbit, providing an evasive, persistent deterrent to discourage further US and allied assistance to Taiwan. Chinese cyber actors intensified operations globally in order to slow US force flow and threaten further horizontal escalation. China invoked its treaty with North Korea to justify military intervention in Korea, while further enhancing bilateral military coordination and setting the stage for permissive deployment of Chinese forces into North Korea. Finally, China conducted anti-ship missile attacks against cargo ships near US west coast and Australian ports.

North Korea conducted a low-yield nuclear strike on a South Korean airbase in an attempt to disrupt air operations against North Korea, split the alliance, and deter further South Korea-US escalation. Separately, North Korea conducted an unarmed nuclear-capable IRBM demonstration, with four missiles impacting outside of territorial waters around Guam, in an attempt to give the United States pause without triggering additional retaliation. North Korea prepared ground forces along the DMZ, posturing its forces for large-scale conventional conflict.

The United States and South Korea agreed to initiate operations to end the North Korean regime in accordance with declaratory policy regarding a North Korean nuclear attack, with CFC forces conducting large-scale ground and air combat operations, as well as a combined strike against Kim Jong Un and senior regime leadership. The blue team, however, was well aware that this operation was risky and might not succeed due to limited US combat power and a lack of munitions available because of the Taiwan conflict—as well as due to North Korea’s nuclear capabilities and extensive Chinese support. To help mitigate the risks of this operation, South Korea initiated an information operations campaign to attempt to co-opt senior North Korean military elites with nuclear use authorities, but this would likely prove too little, too late.

The US team also considered conducting a low-yield nuclear strike against North Korean military forces in the vicinity of Kaesong Heights using a dual-capable aircraft, in an attempt to restore nuclear deterrence, hold North Korea accountable for its limited nuclear use, and halt the creation of a precedent that would allow for an adversary’s nuclear use without a nuclear response, but it was unclear if this would have been approved.

The exercise director adjudicated that South Korean and US presidents would approve a CFC counteroffensive to remove North Korea’s regime despite the risks, even if it was not clear whether a nuclear strike in the Kaesong Heights would be justified and supported. However, considering the military circumstances, the theater military cell was understandably not optimistic about the prospects for success of such a campaign, and the theater military cell overall expected that tactical nuclear exchanges would occur over the course of the campaign. The exercise director considered it likely that the CFC ground counteroffensive would operationally culminate on the approach to Pyongyang due to the Chinese military forces supporting North Korea, particularly with logistics, intelligence, and air defenses. Even in the event that CFC offensive momentum could be maintained or restored, it was likely that North Korea would conduct additional tactical nuclear strikes to stop the advance before Pyongyang could be seized or the regime removed, and it was questionable whether CFC would be sufficiently prepared to fight through these circumstances.

In this situation, it was also likely that the larger US-China war would continue to escalate. China would seize the opportunity to reinforce its attack on Taiwan while the United States committed combat power, munitions, and other resources against North Korea. This could lead to the fall of Taiwan. Regardless of the situation in Taiwan, horizontal escalation of the conflict to other areas, including China’s sea lines of communication, would likely continue. In these circumstances, given the other US and Chinese escalatory options available, and the clear mutual interest in avoiding a China-US nuclear war, it would be possible that tenuous nuclear deterrence could still hold. However, the risk of miscalculation and nuclear escalation between the United States and China would be high, particularly given the potential for multiple nuclear exchanges between North Korean and US forces if the South Korea-US alliance continued efforts to end the North Korean regime.

Findings and recommendations

The Guardian Tiger tabletop exercises explored challenging scenarios in which US-led forces might struggle to win, or even contain, simultaneous conflicts with China and North Korea. In such a future, traditional deterrence models could falter, and allies may act independently to protect their own interests. To address these risks, this chapter identifies the key findings of the exercises—and provides actionable recommendations to enhance strategic and operational preparedness:

Finding 1

- If the United States is engaged in conflict with either China or North Korea, it might not be able to deter the other adversary from escalating the conflict or initiating a separate conflict. The risk of simultaneous conflicts with China and North Korea would compound the difficulties US and allied leaders would face when managing nuclear and other escalation risks in a conflict with either adversary. US allies’ competing views regarding China and North Korea further complicate this dynamic. Even if deterrence of a second potential adversary and assurance of allies could prevent simultaneous conflicts in the Indo-Pacific, such efforts would create strategic and operational costs that would hinder US and allied efforts to defeat the first aggressor. As a conflict with the initial adversary escalates, it may become necessary—and even strategically and/or operationally advantageous—to accept the risk of such simultaneous conflicts rather than remain hamstrung by these costs.

- If a US-China military conflict begins, the exercises suggest that the United States would likely find it difficult to balance the competing requirements of respecting South Korean and Japanese concerns, deterring North Korean opportunism, and refraining from actions that could trigger North Korean or Chinese preemption against USFK. In particular, although the United States might deploy a capability to the region to manage one adversary, it could easily be interpreted as a threat to the other.

- The exercise’s results suggest that, in an escalating conflict, the United States and its allies may unintentionally push Noth Korea and China to align. In particular, the exercises suggest that if South Korea-US responses to North Korean escalation appear likely to cause North Korea to collapse, Washington has little leverage to convince Beijing that it is not in its interest to intervene. Beijing sees grave risks from an imminent North Korean collapse, even if China is not at war with the United States, including North Korea’s absorption by South Korea, and/or a North Korea-initiated nuclear exchange. If a US-China conflict is already under way, Beijing is even more likely to see intervening as less risky than allowing North Korea’s defeat.

Recommendations

- US military planners should update Indo-Pacific command and control arrangements to account for the high risk of simultaneous conflicts with North Korea and China. This should include a review of, and update to, the Unified Command Plan (UCP) specifically focused on ensuring that US command and control arrangements in the Indo-Pacific enable the ability to effectively fight simultaneously in the Korean theater of operations and in the vicinity of Taiwan.

- The US defense community should work with South Korean and Japanese counterparts to better understand the interplay of responses to Chinese and North Korean conventional and nuclear aggression. Despite the political sensitivities at play, considerations of a simultaneous China-North Korea threat should appear regularly on agendas for bilateral and trilateral Track 1 and Track 1.5 dialogues, tabletop exercises, and similar events.

- The US defense community and military commands should sponsor and conduct additional studies and wargaming related to US force and munitions requirements, as well as posture adjustments, to better address the risk of simultaneous conflicts with China and North Korea, including the potential role of the South Korean and Japanese militaries.

Finding 2

- What it takes to prevent North Korea from escalating a conflict will be very different from what it takes to prevent China from doing so. The two countries’ differing escalation imperatives and capabilities will foster complex dilemmas for US and allied deterrence and response options in an Indo-Pacific conflict. Threats of vertical escalation from Pyongyang—particularly threats of tactical nuclear use—are likely to come early and often. Meanwhile, China has many incentives and non-nuclear options to escalate horizontally—across domains (land, maritime, air, space, cyber) and geography, including to the US homeland—to disrupt Washington’s will and capability to support Taiwan. Deterring and countering these different escalation patterns will each require focused capabilities and approaches. This will place competing demands on high-demand, low-density US capabilities like high-end intelligence collection platforms and long-range strike capabilities, while also making it harder to conduct coherent deterrence posturing and messaging.

- As observed in the tabletop exercises, managing vertical escalation in a conflict with North Korea is fraught with potential for miscalculation and alliance management challenges. North Korea has a long history of nuclear threats and signaling with nuclear-capable missiles, which could make it difficult for the United States and its allies to judge whether North Korea is actually about to launch a limited nuclear attack. Meanwhile, North Korea’s growing capability for tactical nuclear strikes makes a ground campaign into North Korea risky, particularly if these forces are not prepared to “fight through.”

- In contrast, the exercises suggested that China’s range of non-nuclear horizontal escalation options is more problematic for the United States to manage than deterring China from vertically escalating to nuclear use. China’s assertion of air and maritime superiority in the Yellow Sea, along with its projection of air defense and ground combat forces into North Korea, limited US and allied options. China’s capability, and likely willingness, to escalate in cyber and space domains—including in ways that affect the US economy and population—allowed the China cell in Guardian Tiger II to impose key costs and disruption on the US team with little risk.

- As observed in the tabletop exercises, managing vertical escalation in a conflict with North Korea is fraught with potential for miscalculation and alliance management challenges. North Korea has a long history of nuclear threats and signaling with nuclear-capable missiles, which could make it difficult for the United States and its allies to judge whether North Korea is actually about to launch a limited nuclear attack. Meanwhile, North Korea’s growing capability for tactical nuclear strikes makes a ground campaign into North Korea risky, particularly if these forces are not prepared to “fight through.”

Recommendations

- The US military should visibly reinforce resilience of US bases in the Indo-Pacific against nuclear and non-nuclear attacks, also enhancing deterrence by denial against limited nuclear strikes. These bases should be required to routinely conduct and publicize rehearsals for such attacks, including training with prepositioned radiological detection and protective equipment.

- The US defense community should lead interagency efforts to review and propose updates for all declaratory policy language and related statements regarding US responses to attacks with weapons of mass destruction and strategic attacks against the US homeland, including Guam. This review should propose how to reconcile the policy statement that “a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought” with the operational and strategic requirements of preparing for a limited nuclear attack by an adversary, to ensure it does not result in a lack of either deterrent credibility or military readiness against such an attack.3“Joint Statement of the Leaders of the Five Nuclear-Weapon States on Preventing Nuclear War and Avoiding Arms Races,” The White House, January 3, 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/01/03/p5-statement-on-preventing-nuclear-war-and-avoiding-arms-races/#:~:text=We%20affirm%20that%20a%20nuclear,deter%20aggression%2C%20and%20prevent%20war.

Finding 3

- War in the Indo-Pacific may start over one flashpoint, but it will quickly become about much more. Escalation—both vertical and horizontal—in a conflict with China and/or North Korea is likely to cause rapid and major shifts in US priorities, attention, and end states, presuming the initial stage of a conflict is not quickly contained or resolved. A war over Taiwan is likely to become about far more than the status of Taiwan itself, including China’s overall regional and global position post-war and the US homeland’s safety. Meanwhile, an escalating South Korea-US conflict with North Korea is likely to become about the future of the global nuclear order, the credibility of US extended deterrence, and the potential unification of the long-divided Korean peninsula—not just about restoring the fragile armistice.

- At the outset of the conflict in both tabletop exercises, overriding US team goals were generally to support allies and partners, defeat the attack, deter further escalation, and return to the status quo. These priorities rapidly changed as the conflict dragged on and escalated, leaving US military forces and non-military elements of power ill-positioned to effectively support the new priorities in a timely manner. The exercises suggested that alliance and US domestic imperatives will rapidly overtake any potential impetus to return to the status quo, in favor of punishing the aggressors and responding to mushrooming threats facing US and allied homelands.

- In both exercises, a North Korean limited nuclear strike against a military target in South Korean territory immediately brought to the forefront the need for key considerations during the US response to a limited nuclear strike. This includes larger global ramifications, long-term precedent for extended nuclear deterrence, and implications for US alliances beyond the US declaratory policy—that any North Korean nuclear attack will lead to the end of the regime—or the operational and strategic needs of the moment. In Guardian Tiger I, having avoided a US-China war so far, and with Chinese forces inside North Korea, there was little appetite for a nuclear or ground offensive to remove the regime. In Guardian Tiger II, US-China conventional war had already begun, so North Korea’s nuclear attack triggered a US-South Korea ground counteroffensive to remove the regime, despite the risks.

- At the outset of the conflict in both tabletop exercises, overriding US team goals were generally to support allies and partners, defeat the attack, deter further escalation, and return to the status quo. These priorities rapidly changed as the conflict dragged on and escalated, leaving US military forces and non-military elements of power ill-positioned to effectively support the new priorities in a timely manner. The exercises suggested that alliance and US domestic imperatives will rapidly overtake any potential impetus to return to the status quo, in favor of punishing the aggressors and responding to mushrooming threats facing US and allied homelands.

Recommendations

- US defense leadership should publicly and privately underscore the risk that a Chinese attack on Taiwan could lead to a broader regional conflict, even if Beijing and Washington seek to avoid one, as a means to foster allied preparedness and reinforce deterrence.

- The US defense community, in cooperation with relevant combatant commands, should enhance awareness, resilience, and response measures for risk of Chinese non-nuclear strategic attacks on the US homeland in the event of a conflict to reduce the risk of strategic paralysis from such threats and to enable effective responses to such attack. The Department of Defense should support such efforts from the perspective of potential chemical and biological attacks.

Finding 4

- The United States needs to prepare for the possibility of a limited nuclear attack—including preparing responses other than the threat of complete annihilation. The US and allied approach to counter the growing threat of limited nuclear attack by an adversary currently relies on deterrence by threat of massive punishment. This is a high-risk approach. For example, the United States’ current declaratory policy toward North Korea—that any use of a nuclear weapon will lead to the end of the North Korean regime—is likely to lack credibility by 2030. The tendency to avoid the hard political and military choices necessary to better absorb a limited nuclear strike, and to prepare to operate effectively in the aftermath, means there might be no good conventional options left if such threats of disproportionate punishment fail. Meanwhile, US low-yield nuclear response capabilities are being intentionally limited, meaning that available nuclear responses may be seen as ineffective or excessive.

- The exercises suggest that the threat of massive, regime-ending nuclear retaliation might not work, at least by the year 2030. The North Korea cell noted that, from its perspective, restatement of existing US declaratory policy for North Korea during the exercises was simultaneously provocative—by emphasizing regime change—and lacking in credibility. As noted above, the exercises showed some plausible scenarios in which the North Korean regime could use nuclear weapons and survive.

- These exercises provided further evidence of the strong tendency among the United States and its allies to avoid taking the actions necessary to better absorb a limited nuclear strike and to prepare to operate effectively in the aftermath of such a strike until it might be too late.

- The exercises suggest that the threat of massive, regime-ending nuclear retaliation might not work, at least by the year 2030. The North Korea cell noted that, from its perspective, restatement of existing US declaratory policy for North Korea during the exercises was simultaneously provocative—by emphasizing regime change—and lacking in credibility. As noted above, the exercises showed some plausible scenarios in which the North Korean regime could use nuclear weapons and survive.

Recommendations

- US defense and military planners working with their South Korean counterparts, should examine the operational and strategic implications of the South Korea-US declaratory policy on a North Korean nuclear attack. This should lead to renewed efforts to enhance the credibility to execute this policy and to bring an end to the North Korean regime—regardless of the potential for Chinese interference or North Korean nuclear retaliation. This should also lead to preparations for the possibility that this declaratory policy will fail to deter a North Korean limited nuclear attack. The United States should also consider this policy’s implications vis-à-vis Beijing.

- The US Department of Defense should enhance preparations to quickly provide education, training, and analytic support to US forces and US allies in the Indo-Pacific to better enable preparations for low-yield nuclear weapons effects. Ideally, the United States should execute such activities pre-crisis as much as possible, moving quickly to expand these activities in the event that changing domestic political circumstances or crisis urgency on the part of an ally makes such expansion possible. Additional studies, exercises, wargames, and tabletop exercises should include US allies and focus specifically on possible limited nuclear attacks by adversaries in the Indo-Pacific.

- The US defense community and military commands should train and equip US forces to fight and win despite tactical nuclear attacks, and should encourage allied counterparts to do so as well.

Finding 5

- Effective integrated deterrence and escalation management in the Indo-Pacific will require the United States to simultaneously coordinate with allies and perform informational shaping at multiple echelons, and across multiple military commands and government agencies, prior to the outbreak of conflict. This would involve establishing stronger combined (multinational) command and control, coordination, and planning mechanisms between the United States and its allies in advance of a crisis that could lead to conflict, including both military and non-military organizations at multiple levels. Traditional top-down approaches and “wartime only” structures will be suboptimal given the speed at which situations could escalate. The Guardian Tiger exercises further demonstrated how difficult it is to coordinate such a top-down response in a timely manner, especially without sufficiently prepared mechanisms. Key US allies—particularly Japan and South Korea—will unilaterally use capabilities and send messages if they are not part of a better plan.

- The United States will not be able to conduct integrated deterrence and warfighting against China and/or North Korea without close allied coordination. At minimum, countering Chinese threats to Taiwan will require Japanese support, while South Korean forces are foundational for countering North Korea.

- Synchronizing military actions between allies to manage escalation requires close lateral coordination between allied militaries below top-level political coordination. The speed at which a conflict could develop and escalate means that multiple military and informational options may need to be offered in a bottom-up manner, while top-level guidance is developed simultaneously. The exercises further demonstrated the difficulties in alliance coordination, especially without good structures in place. South Korea-US-Japan operational coordination was particularly hamstrung in Guardian Tiger II due to the separation between CFC/USFK and USFJ.

- The United States will not be able to conduct integrated deterrence and warfighting against China and/or North Korea without close allied coordination. At minimum, countering Chinese threats to Taiwan will require Japanese support, while South Korean forces are foundational for countering North Korea.

Recommendations

- US defense leadership should update the UCP to address the importance of enhanced capacity for bilateral and multilateral operational-level alliance military coordination in East Asia. This should include a capability for more robust operational coordination with the Japanese Self Defense Force than what is possible with the existing USFJ structure. Given the importance of varied basing options in the Indo-Pacific for a resilient posture in the face of attack, and the capabilities that Japan and South Korea can bring to bear, the ability of headquarters to coordinate with allies may be as important—or even more important—than their ability to command and control US-only joint operations.

- US government organizations sponsoring integrated deterrence exercises, wargames, and tabletop exercises should ensure they include more robust methodology for depicting informational tools and aspects as part of integrated deterrence. This should include the simulation of US and allied targeting and effects of informational actions on sub-national audiences, as well as depictions of adversary information operations targeting such audiences.

- US government organizations sponsoring integrated deterrence exercises, wargames, and tabletop exercises should ensure that these events represent multiple echelons of US and allied governments and military forces—ideally including allied personnel as participants—to enable the simulation of US-ally engagement at multiple echelons.

Acknowledgments

The principal investigator thanks the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA), particularly the Strategic Trends team, for sponsorship, guidance, support, and resources for this study. Thanks also go to all the experts and stakeholders, inside and outside of government, who participated in the tabletop exercise and contributed their perspectives to enrich the analysis. Special appreciation goes to multiple members of the staffs of the Department of State, the Office of the Secretary of Defense, the US Defense Intelligence Agency, Air Force Futures, the United States Strategic Command (USSTRATCOM), the South Korea-US Combined Forces Command, the US Forces Korea, and the 7th US Air Force for their willingness to repeatedly donate their time to inform this project with their invaluable personal perspectives.

The principal investigator would also like to give special thanks to co-authors Lauren Gilbert and Kyoko Imai, as well as current Indo-Pacific Security Initiative team members Emily Kim and Audrey Roh, along with former members Katherine Yusko and Emma Verges, for their key supporting roles in this project, as well as to project consultant Gregory Park for his contributions to the execution of the exercises and the drafting of the report. Thanks also go to Frederick Kempe, the Atlantic Council’s president and chief executive officer, as well as Gretchen Ehle, Nicholas O’Connell, and Caroline Simpson, without whose support the resources for this project would not have been possible. Lastly, the principal investigator would like to share his deepest appreciation for vice president and Scowcroft Center senior director Matthew Kroenig’s support and encouragement for this ambitious project from its very inception. This report is intended to live up to General Brent Scowcroft’s standard for rigorous, relevant, and nonpartisan analysis on national security issues.

This report reflects the analysis of the authors and does not necessarily represent the position of the DTRA or any other US government organization.

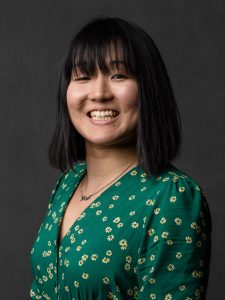

About the authors

The Tiger Project, an Atlantic Council effort, develops new insights and actionable recommendations for the United States, as well as its allies and partners, to deter and counter aggression in the Indo-Pacific. Explore our collection of work, including expert commentary, multimedia content, and in-depth analysis, on strategic defense and deterrence issues in the region.

Related content

Explore the program

The Indo-Pacific Security Initiative (IPSI) informs and shapes the strategies, plans, and policies of the United States and its allies and partners to address the most important rising security challenges in the Indo-Pacific, including China’s growing threat to the international order and North Korea’s destabilizing nuclear weapons advancements. IPSI produces innovative analysis, conducts tabletop exercises, hosts public and private convenings, and engages with US, allied, and partner governments, militaries, media, other key private and public-sector stakeholders, and publics.

Image: North Korean leader Kim Jong Un meets President Xi Jinping in Beijing, China, in this photo released by North Korea's Korean Central News Agency (KCNA) on January 10, 2019.