Deterrence is crumbling in Korea: How we can fix it

Introduction

Sir Lawrence Freedman1Freedman is a deterrence scholar and an emeritus professor of war studies at King’s College London. This oft-cited quote is credited to him in: “Nuclear Weapons—The Unkicked Addiction,” The Economist, March 7, 2015, https://www.economist.com/briefing/2015/03/07/the-unkicked-addiction.

Deterrence works, until it doesn’t.

The time is now ripe to revisit the future of deterrence on and around the Korean Peninsula.

The Korean Peninsula is frequently held up as an example of the effectiveness of US extended deterrence guarantees, and of deterrence in general. Since the signing of the military armistice that brought an end to the Korean War in 1953 without a peace treaty, deterrence has been the watchword in maintaining an uneasy de facto peace. Though North Korea has engaged in threatening rhetoric and saber-rattling, development of weapons of mass destruction in defiance of United Nations (UN) resolutions, and even occasional acts of limited violence, deterrence of a major attack has held firm for nearly seventy years. While some skeptics question whether a nuclear-armed North Korea can be reliably deterred at all, the consensus among national security experts and politicians alike seems to be that deterrence will continue to hold in Korea.2For examples of skepticism on the ability to deter North Korea, see Alex Lockie, “McMaster Thinks North Korea Can’t Be Stopped from Attacking the US or Allies,” Business Insider, August 14, 2017, https://www.businessinsider.com/hr-mcmaster-north-korea-war-inevitable-deterrence-2017-8; Uri Friedman, “John Bolton’s Radical Views on North Korea,” The Atlantic, March 23, 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2018/03/john-bolton-north-korea/556370/.

As a result, US efforts to shore up deterrence are primarily focused elsewhere, where deterrence seems to be much more at risk. When deterrence in Korea is mentioned at all by Americans, it is typically in terms designed to reassure allies that deterrence is strong rather than convey concern.3For example, see Katrin Fraser Katz, Christopher Johnstone, and Victor Cha, “America Needs to Reassure Japan and South Korea,” Foreign Affairs, February 9, 2023, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/japan/america-needs-reassure-japan-and-south-korea. In line with this perspective, a study by a prominent US research organization projected deterrence in Korea as “healthy,” in marked contrast to the “mixed” situation in the Taiwan Strait.4Michael J. Mazarr, Nathan Beauchamp-Mustafaga, Timothy R. Heath, and Derek Eaton, What Deters and Why: The State of Deterrence in Korea and the Taiwan Strait, RAND Corporation, 2021, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR3144.html. Deterring aggression against Taiwan is becoming an increasingly central focus of US public discussions on defense issues, with some high-level defense officials suggesting that the People’s Republic of China (PRC) might attempt forcible reunification before the close of the decade if not deterred.5Jim Garamone, “U.S. Strengthening Deterrence in Taiwan Strait,” DOD News, Department of Defense, September 19, 2023, https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/3531094/us-strengthening-deterrence-in-taiwan-strait/; Jerry Hendrix, “Closing the Davidson Window,” RealClear Defense, July 3, 2021, https://www.realcleardefense.com/articles/2021/07/03/closing_the_davidson_window_784100.html Meanwhile, with Russia having successfully conducted a land grab of Crimea in 2014, and now threatening nuclear escalation in the midst of a full-scale war against Ukraine, deterrence in Eastern Europe appears to be teetering on a knife’s edge, perhaps more fragile than in the Taiwan Strait.

In comparison to the might of Russia and the PRC, and the ambiguity of US defense commitments to Taiwan and Ukraine, effective deterrence in Korea appears simple—at first glance. It is hard to imagine why North Korea, a destitute country, with half the population and a tiny fraction of the wealth of the Republic of Korea (ROK; South Korea)—also backed by the United States—would not be deterred. Given that the Pyongyang regime seems vastly outmatched, so long as Washington or Seoul does not start a conflict, the conventional wisdom is that Pyongyang would not dare risk war or nuclear weapons use for the foreseeable future. As is typical of conventional wisdom, this premise’s logic is simple, its implications are comforting, and it is hard to disprove.

However, this conventional wisdom on deterrence in Korea could prove wrong—disastrously so. Upon examination, confidence in the strength of deterrence in Korea is based on a backward look at long-standing assumptions that are no longer tenable and politico-military conditions that have already begun to shift and are very likely to change even more dramatically in the next five to ten years. As a result, even when deterrence in Korea is examined in depth, such assessments are typically based on the premise of reinforcing it against erosion, not a fundamental re-look.

To address this analytic gap, we undertook the “Preventing Strategic Deterrence Failure on the Korean Peninsula” study to instead look forward at the future conditions for deterrence in Korea five to ten years from now, assess the challenges, and recommend actionable mitigation measures. By convening more than one hundred outside experts and stakeholders, consulting extensive existing literature, and conducting a virtual tabletop exercise, this study identified and examined key variables expected to drive the potential for escalation on the Korean Peninsula over the next decade and provided actionable analysis to help avoid a strategic deterrence failure on the Korean Peninsula.

It is infeasible to deter every possible North Korean transgression, so this study was designed to focus on the risk of strategic deterrence failure, defined by this study as “adversary escalation to nuclear weapons strikes and/or to full-scale armed conflict against the United States or the Republic of Korea.” To keep its scope manageable, the study concentrated on deterrence of military action involving the mass deaths of US and/or allied citizens, excluding less lethal scenarios such as major cyberattacks.

This report summarizes the study’s findings, including analysis of the evolving threat capabilities and intentions of North Korea and the PRC, layered against the future deterrent posture of the United States and its allies, to synthesize new insights. The main body of the report concludes with a series of five analytic key findings and corresponding actionable recommendations for the US government and military.

Findings summary

The study found that ongoing changes in North Korean and PRC capabilities and intentions are very likely to drive a dramatically increased risk of strategic deterrence failure on or around the Korean Peninsula in the next five to ten years while the current trajectory of South Korean and US deterrence capabilities and approaches looks unlikely to effectively mitigate these risks. If the United States, in concert with South Korea, does not undertake major adjustments to its capabilities and approaches to strengthen deterrence and resilience in the face of aggression in and around the Korean Peninsula—changes that would admittedly incur significant political and economic costs—to counteract these drivers and mitigate these risks, the probability of strategic deterrence failure will increase in comparison to today, while the likely operational and strategic consequences for such failure will also increase.

Five key findings of the study are summarized below and are explored later in greater detail along with corresponding recommendations to address the implications of these findings.

- Of all the potential scenarios for strategic deterrence failure in the next decade, Pyongyang seizing an opportunity to launch a full-scale attack to reunify the Korean Peninsula is one of the least plausible. The path toward strategic deterrence failure is far more likely to begin with limited North Korean coercive escalation. Such coercion could result in an escalation cycle fueled by limited South Korean or US responses that lead Pyongyang to escalate further to retake the initiative, which would then drive escalation dynamics that trigger North Korea to launch a preemptive or preventive attack and motivate Beijing to intervene.

- This study focused on strategic deterrence failure and made no judgment as to the other strategic risks of adversaries’ coercion. However, these risks comprise an important subject for future study, as the US 2023 North Korea National Intelligence Estimate identifies coercion as the Kim regime’s most likely strategy for achieving its foreign policy objectives through 2030.6US Office of the Director of National Intelligence, North Korea: Scenarios for Leveraging Nuclear Weapons through 2030, National Intelligence Estimate, June 15, 2023, https://www.dni.gov/files/ODNI/documents/assessments/NIC-Declassified-NIE-North-Korea-Scenarios-For-Leveraging-Nuclear-Weapons-June2023.pdf, i.

- We assessed that US and South Korean concessions as a tactic to de-escalate a confrontation are probably not a viable long-term approach, or one that could be used repeatedly without incurring high risks and costs. Such concessions would probably undermine deterrence and fuel a high-risk pattern by generating overconfidence in Pyongyang and Beijing.

- A combination of more precise and capable conventional options for North Korea with a more robust second-strike nuclear deterrent will challenge the credibility of US deterrence by punishment over the next five to ten years, increasing the level to which North Korea believes it can escalate without triggering a regime-ending response. As Pyongyang grows more confident in its own nuclear deterrent and in the likelihood of assertive PRC involvement in Korea to counter its strategic rival, the United States, Pyongyang’s perceived viable escalatory options to either press its advantage or retake the initiative will increase in intensity and diversity.

- The likelihood of PRC intervention and interference in a Korea crisis will increase in the coming decade, as PRC military capabilities grow and the PRC-US strategic rivalry heightens. The ROK-US alliance is not yet politically or militarily postured to deter or defeat PRC intervention, and both partners seem unwilling to pay the political costs to confront this growing challenge more directly. This is likely to encourage North Korean adventurism and complicate ROK-US deterrent responses, particularly in the Yellow Sea (also known as the West Sea) near China.

- The ROK-US alliance military posture (including authorities, capabilities, command structure, readiness, and training) has not been designed for the full spectrum of conflict from limited provocations to full nuclear war, and that is not on a path to change in the next ten years. This posture is designed almost exclusively for two possibilities: ROK self-defense against small-scale “provocation” by North Korea or a deliberate transition to combined ROK-US war operations in a large conventional war with North Korea. This posture is unsuited for a rapid, but limited, response to an attack beyond a provocation but short of full-scale war. It is also unsuited for deterring or defeating PRC intervention, or for fighting a war that includes nuclear strikes—all possibilities that the United States and its allies should prepare for.

- Pyongyang’s regime almost certainly knows it cannot survive if it triggers an all-out nuclear exchange, but it will probably see greater viability for limited nuclear employment in the next five to ten years. If North Korea were to employ a nuclear weapon, it would most likely be in a limited manner intended to pose a dilemma for and constrain the ROK-US (and PRC) response. North Korea’s increasing capability to conduct a limited nuclear “demonstration” or tactical strike will give North Korea options that could undermine US extended deterrence globally, even if the immediate US response to such use prevents a catastrophic near-term strategic deterrence failure.

Analysis

The study’s analysis, summarized below, began with a focus on adversaries, including a forecast of the key variables impacting how future North Korean and PRC capabilities and intentions could affect the risk of strategic deterrence failure on the Korean Peninsula. The study then layered atop this analysis an assessment of how key US and allied capabilities, actions, and postures would either exacerbate or counteract those drivers. Finally, based on this synthesis, and with the help of many experts and stakeholders, the study laid out actionable recommendations for the US government, defense organizations, and military to better counteract or mitigate the risks of strategic deterrence failure.

Rising deterrence challenges from Pyongyang and Beijing

Taken individually, the PRC and North Korea each already pose growing risks to US efforts to maintain strategic deterrence in the Indo-Pacific. Recent studies warn of the PRC’s increasing capacity to threaten strategic deterrence over the next ten years, while others examine how the growth of North Korean nuclear and missile capabilities in particular is likely to strain US extended deterrence.7See Matthew Kroenig, Deterring Chinese Strategic Attack: Grappling with the Implications of China’s Strategic Forces Buildup, Atlantic Council, November 2, 2021, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/report/deterring-chinese-strategic-attack-grappling-with-the-implications-of-chinas-strategic-forces-buildup/; Markus Garlauskas, Proactively Countering North Korea’s Advancing Nuclear Threat, Atlantic Council, December 23, 2021, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/report/proactively-countering-north-koreas-advancing-nuclear-threat/; Markus Garlauskas, “The Evolving North Korean Threat Requires an Evolving Alliance,” in The Future of the US-ROK Alliance, Atlantic Council, February 2021, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Chapter-4.pdf; Adam Mount, Conventional Deterrence of North Korea, Federation of American Scientists, December 18, 2019, https://fas.org/pub-reports/conventional-deterrence-of-north-korea/; Ankit Panda, “Hwasong-12 Test Signals Troubling New Phase in North Korea’s Missile Programs,” NK Pro, January 31, 2022, https://www.nknews.org/pro/hwasong-12-test-signals-troubling-new-phase-in-north-koreas-missile-programs/?t=1652220223738. These two challenges are likely to combine to further heighten the challenges for strategic deterrence around the Korean Peninsula in the coming decade; according to the US 2023 North Korea National Intelligence Estimate, for instance, North Korea is more likely to pursue an offensive (rather than coercive) strategy if it believes it can do so while retaining PRC support.8US Office of the Director of National Intelligence, North Korea, i.

North Korea’s capabilities and intentions in the next decade

As noted above, Korea has arguably been the longest-standing consistent strategic deterrence success story, even if denuclearization efforts have failed. However, the trajectory of North Korea’s capabilities, combined with the coercive approach of Kim Jong Un’s leadership, suggests that this “golden age” for deterrence in Korea may soon come to an end. Even though it is unlikely for Pyongyang to believe it could reunify Korea by force or to embark on “a war of choice” that would risk the regime’s survival, its expected capability and intent to further stretch the boundaries of limited escalation—as part of its coercive approach—will put strategic deterrence at risk.

The study began with a foundational examination of current North Korean capabilities. Of these capabilities, we assess that North Korea will only have sufficient resources available to maintain the majority as “legacy” capabilities, with limited incremental or niche improvements at best. These “legacy forces” will remain sufficiently formidable, however, to still factor in North Korean and South Korean escalatory calculus in the coming decade. They include the following:

- A large and slowly modernizing, but qualitatively inferior and poorly sustained, ground force, with hundreds of thousands of personnel and thousands of armored vehicles—a force incapable of seizing and occupying the Korean Peninsula in the face of the ROK military’s defensive capabilities, but capable of limited offensive operations and defense of North Korea against a counterattack9See Kim Min-seok, The State of the North Korean Military, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, March 18, 2020, https://carnegieendowment.org/2020/03/18/state-of-north-korean-military-pub-81232.

- Large numbers of relatively inaccurate rocket and gun artillery systems capable of massing large volumes of fire, including a small proportion that can reach the greater Seoul Metropolitan Area and a range of systems able to deliver chemical munitions10See D. Sean Barnett et al., North Korean Conventional Artillery: A Means to Retaliate, Coerce, Deter, or Terrorize Populations, RAND Corporation, 2020https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA619-1.html.

- Large numbers of special operations forces, with the ability to operate at night, with multiple means of airborne, maritime, and land insertion and infiltration to reach targets in South Korea11Defense Intelligence Agency, North Korea Military Power: A Growing Regional and Global Threat, 2021, https://www.dia.mil/Portals/110/Documents/News/NKMP.pdf

- Dozens of mobile liquid-fueled and chemical-, nuclear-, and conventional-capable ballistic missile systems that can reach all of South Korea and most US bases in Japan (e.g., Scud and No Dong)12See “Hwasong-7 (Nodong 1),” Missile Threat, Center for Strategic and International Studies, August 9, 2016, last modified July 31, 2021, https://missilethreat.csis.org/missile/no-dong/; “KN-18 (Scud MaRV),” Missile Threat, Center for Strategic and International Studies, April 18, 2017, last modified July 31, 2021, https://missilethreat.csis.org/missile/kn-18-marv-scud-variant/.

- Coastal defense artillery, surface naval combatants, naval mines, fighter aircraft, and surface to air missiles in sufficient numbers to contest the airspace and waters surrounding North Korea at least temporarily13Defense Intelligence Agency, North Korea Military Power, 32.

- Diesel-electric attack submarines capable of contesting the waters around the Korean Peninsula and of ambiguous limited aggression with special operators, undersea mines, and surprise torpedo attacks14Ibid., 50-52.

- Millions of paramilitary and reserve personnel capable of supporting the defense of North Korea from a ground invasion, enabling domestic stability and control in a crisis, and potentially conducting guerilla warfare against foreign military forces operating in their home areas15Benjamin R. Young, “Guns in One Hand: Kim Jong Un’s Revitalization of the Worker-Peasant Red Guards,” NK News, September 17, 2021, https://www.nknews.org/2021/09/guns-in-one-hand-kim-jong-uns-revitalization-of-the-worker-peasant-red-guards/.

- Large stockpiles of chemical weapons and a bioweapons program with access to a wide variety of agents but uncertain volume of production capacity16John V. Parachini, “Assessing North Korea’s Chemical and Biological Weapons Capabilities and Prioritizing Countermeasures,” RAND Corporation, 2018, https://www.rand.org/pubs/testimonies/CT486.html.

- Thousands of underground facilities that provide cover, concealment, denial, and deception for North Korean facilities, forces, and logistics, as well as command and control and other supporting assets17Kyle Mizokami, “North Korea’s Underground Bunkers and Bases Are a Nightmare for America,” The National Interest, January 10, 2020, https://nationalinterest.org/blog/buzz/north-koreas-underground-bunkers-and-bases-are-nightmare-america-112586.

In addition to these already-formidable legacy assets, North Korea is very likely to further develop its capabilities in several important categories, based on recent weapons tests, displays, and Kim Jong Un’s public guidance. These capabilities have all been at least partially established already but will likely improve markedly in the next five to ten years.

- Growing numbers of new mobile close-, short-, and medium-range ballistic missiles, along with maneuvering (hypersonic) reentry vehicles and cruise missile systems, increasing capability to evade or overwhelm defenses, and improving accuracy to hit point targets with conventional, chemical, or nuclear warheads18See Missile Defense Project, “Missiles of North Korea,” Missile Threat, Center for Strategic and International Studies, June 14, 2018, last modified June 14, 2021, https://missilethreat.csis.org/country/dprk/.

- A nascent ballistic missile submarine capability, sufficient to reinforce North Korea’s second-strike nuclear capability against targets in Northeast Asia and help overcome missile defense of the ROK19Defense Intelligence Agency, North Korea Military Power, 50; Markus Garlauskas and Bruce Perry, “What an ‘October Surprise’ from North Korea Might Actually Look Like,” The New Atlanticist, Atlantic Council, October 1, 2020, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/what-an-october-surprise-from-north-korea-might-actually-look-like/.

- Mobile liquid- and solid-fuel intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and intermediate-range ballistic missiles (IRBMs), with multiple reentry vehicles and other defense evasion measures sufficient to pose a credible second-strike nuclear threat to Guam, Alaska, and the continental United States (CONUS)20Markus Garlauskas, Proactively Countering North Korea’s Advancing Nuclear Threat, Atlantic Council, December 23, 2021, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/report/proactively-countering-north-koreas-advancing-nuclear-threat/.

- Cyberattack capabilities sufficient to achieve disruptive and destructive effects, particularly on civilian targets21“Guidance on the North Korean Cyber Threat,” National Cyber Awareness System, Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, April 15, 2020, last updated June 23, 2020, https://www.cisa.gov/uscert/ncas/alerts/aa20-106a.

- Increasing quantity and sophistication of unmanned aerial systems, to include various ranges and types for tactical, operational, and strategic-level reconnaissance and targeting, as well as some attack capability22Defense Intelligence Agency, North Korea Military Power, 39.

- Growing stockpile of fissile material and nuclear warheads (over fifty), including previously tested fission and thermonuclear warheads, and probably including tactical nuclear warheads23Hans M. Kristensen and Matt Korda, “North Korean Nuclear Weapons, 2021,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 77, no. 4 (July 2021): 222-36, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00963402.2021.1940803.

- Includes the Hwasan-31, a new nuclear warhead introduced in March 2023 that could be small enough to fit on missiles capable of striking South Korea and Japan;24Pablo Robles and Choe Sang-Hun, “Why North Korea’s Latest Nuclear Claims Are Raising Alarms,” New York Times, June 2, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2023/06/02/world/asia/north-korea-nuclear.html. posters depicted in a North Korean press release25North Korea Unveils New Nuclear Warheads as U.S. Air Carrier Arrives in South Korea,” NBC News, March 28, 2023, Source: Reuters, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/north-korea-unveils-new-nuclear-warheads-us-air-carrier-arrives-south-rcna76944. indicate that the Hwasan-31 could be delivered via autonomous torpedo, close-range ballistic missile, two different types of cruise missile, and five different types of short-range ballistic missile, which can be fired from mobile launchers and trains26Ankit Panda, email message to Katherine Yusko, October 12, 2023.

- New mobile surface to air and anti-ship missile systems to boost the defense of North Korea’s airspace and coastline

Together, all these capabilities provide Pyongyang with many options to escalate, dissuade, or defeat ROK-US alliance military responses, providing the basis for Pyongyang’s potential to challenge strategic deterrence.

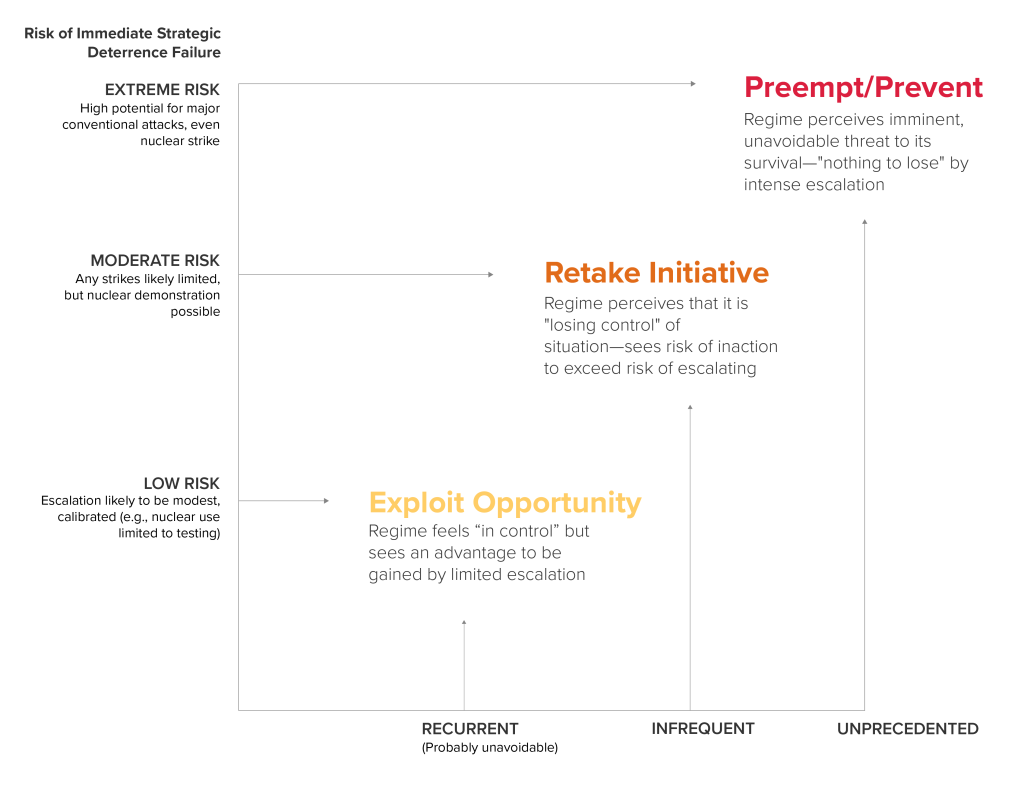

There are three overall mindsets in which we judge that North Korea would choose to use one of these capabilities to escalate, which we have termed “exploit opportunity,” “retake initiative,” or “preempt/prevent” (see Figure 1). Though domestic politics and threat factors figure into these three categories, escalation driven primarily by domestic considerations—a “diversionary war,” for example—was considered out of the study’s scope.

The first mindset is one in which North Korea perceives itself to be in control and is escalating for limited political or military advantage to “exploit opportunities,” as it frequently does. This would be a mindset of relatively low risk acceptance, so escalation driven by this logic would almost certainly fall well short of strategic deterrence failure, barring tremendous overconfidence on Pyongyang’s part. This would typically lead to fairly modest escalation, like a missile test or demonstration. However, it is difficult, if not impossible, to deter escalation under this logic entirely, even if such escalation would be quite limited. This difficulty is still problematic for US interests because it means it would probably not be viable to deter North Korean coercive threats and demonstrations, as well as weapons testing, through military means.

The second mindset is one in which North Korea is escalating to “retake initiative.”27North Korea’s September 2022 law on state policy for nuclear forces lists “taking the initiative in war” as one of the cases in which it may employ nuclear weapons: see “Law on DPRK’s Policy on Nuclear Forces Promulgated,” Korean Central News Agency, September 9, 2022, http://kcna.kp/en/article/q/5f0e629e6d35b7e3154b4226597df4b8.kcmsf. This would be a less likely, but more dangerous, mentality, wherein Pyongyang senses it is losing control of events that are taking a threatening path and escalates to regain control of the situation before it deteriorates too far. Risk acceptance in this situation is higher, as the risks and costs of doing nothing are also significant. (Pyongyang would be in “the domain of losses” as described by prospect theory.)28For more on prospect theory, see Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, “Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk,” Econometrica 47, no. 2 (March 1979): 263-292, https://www.jstor.org/stable/1914185; and Kai He and Huiyun Feng, Prospect Theory and Foreign Policy Analysis in the Asia Pacific (London: Routledge, 2017), https://www.routledge.com/Prospect-Theory-and-Foreign-Policy-Analysis-in-the-Asia-Pacific-Rational/He-Feng/p/book/9781138107939. It would be challenging to deter Pyongyang from any escalation at all when such logic applies, but we judge it would be possible to deter extreme options leading immediately to strategic deterrence failure.

The third mindset is one of “preemptive/preventive” escalation, the least likely but most dangerous. If Pyongyang perceives that a war or other outside attempt to end the regime (such as “decapitation strikes” or a foreign-sponsored coup) is unavoidable and imminent, it is likely to escalate steeply. This is logical—North Korea could gain a military advantage by striking first rather than trying to ride out a wave of alliance precision strikes—but it also fits within North Korea’s long-standing public narrative and its September 2022 law on state nuclear policy.29For one of many examples of open-source analysis of North Korea’s public statements related to preemption, see Léonie Allard, Mathieu Duchâtel, and François Godement, Pre-empting Defeat: In Search of North Korea’s Nuclear Doctrine, European Council on Foreign Relations, November 22, 2017, https://ecfr.eu/publication/pre_empting_defeat_in_search_of_north_koreas_nuclear_doctrine/; for more on Pyongyang’s September 2022 law expanding the range of conditions under which it could launch a preemptive nuclear strike, see Josh Smith, “New North Korea Law Outlines Nuclear Arms Use, Including Preemptive Strikes,” Reuters, September 9, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/nkorea-passes-law-declaring-itself-nuclear-weapons-state-kcna-2022-09-08/. This attack could be designed around the military imperatives of inflicting maximum damage as quickly as possible. Such an attack could also be relatively limited and calibrated, conducted under the logic of “escalating to de-escalate” in the hope that a robust but limited first strike combined with a credible second-strike threat would allow negotiation of a quick end to hostilities on terms allowing the regime to survive.

- This is the most challenging situation for calibrating a military posture for strategic deterrence since once Pyongyang is in this mindset, a diplomatic “off-ramp”—even one guaranteed by Beijing—may not be credible. Unless Pyongyang trusts that such an off-ramp is truly credible, signs of vulnerability or hesitation could encourage Pyongyang to seize a fleeting window of opportunity to strike first, while a strengthening US posture could just trigger quicker or more intense escalation. Therefore, the best way to prevent strategic deterrence failure in such a situation is simply to avoid it in the first place.

China’s capabilities and intentions in the next decade

During a future Korean Peninsula crisis, the PRC could indirectly influence Pyongyang’s escalation calculus in a way that contributes to strategic deterrence failure, or could itself directly intervene militarily and escalate against US or South Korean forces to the point of a strategic deterrence failure. Yet, despite this potential, in comparison to the many studies of PRC capabilities and intentions in a Taiwan scenario, the PRC’s role in a future Korea contingency is under-examined. As a result, the study required new estimates of how the PRC’s capabilities and intentions would evolve vis-à-vis Korea, which were developed based on unclassified Defense Intelligence Agency and Department of Defense (DOD) analysis, augmented by academic publications, and refined with the assistance of study participants.

As a foundation for understanding the PRC’s role in a Korea crisis, the study first established a forward-looking estimate of China’s capabilities in the next ten years, as these capabilities—even if primarily developed for purposes other than a Korea contingency—would open options and leverage for Beijing not previously available. In summary, we judged that PRC capabilities related to a Korea contingency will almost certainly include the following:

- Strategic and tactical nuclear capabilities sufficient to threaten “counter-force” first use (against military targets), and to hold multiple major cities in the US homeland at risk with nuclear weapons in a “counter-value” second strike (against cities)30“Nuclear Second-Strike Capability,” Asia Power Index 2021 Edition, Lowy Institute, https://power.lowyinstitute.org/data/resilience/nuclear-deterrence/nuclear-second-strike-capability/; China Power Team, “Does China Have an Effective Sea-Based Nuclear Deterrent?” China Power, December 28, 2015, https://chinapower.csis.org/ssbn/.

- Ballistic and cruise missiles (conventional and nuclear) capable of striking all US and allied bases in South Korea, Japan, and Guam with mass and precision—including overcoming missile defenses to a degree31Missile Defense Project, “Missiles of China,” Missile Threat, Center for Strategic and International Studies, June 14, 2018, last modified April 12, 2021, https://missilethreat.csis.org/country/china/; Eric Heginbotham et al., Chinese Attacks on U.S. Air Bases in Asia: An Assessment of Relative Capabilities, 1996-2017, RAND Corporation, 2015, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RB9858z2.html.

- Air defense systems capable of tracking (and threatening) air operations over the entire Korean Peninsula and approaches, including systems less than one hundred miles from Korea on the Shandong Peninsula32US Office of the Secretary of Defense, Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China: Annual Report to Congress, 2021, https://media.defense.gov/2021/Nov/03/2002885874/-1/-1/0/2021-CMPR-FINAL.PDF, 120; “China Flight-Tests Missile Interceptors,” Arms Control Today, Arms Control Association, April 2021, https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2021-04/news-briefs/china-flight-tests-missile-interceptors.

- Air, air defense, coastal defense, surface and subsurface platforms, and sensors sufficient for robust situational awareness and clear operational military superiority in and over the Yellow (West) Sea33For a map of People’s Liberation Army weapons systems and deployments in the Northern Theater, see US Office of the Secretary of Defense, Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China, 112.

- Options to quickly move military forces onto the Korean Peninsula, including sealift, limited airborne and airmobile operations into parts of North Korea, and amphibious landings on the west coast of the peninsula34Ibid., 110.

- Land combat power and logistical support sufficient for large-scale sustained overland intervention across the Yalu River throughout North Korea, supported by airpower, missiles, and a mobile air defense umbrella35For an account of Chinese land combat power, see Anthony H. Cordesman, Chinese Strategy and Military Forces in 2021, Center for Strategic and International Studies, https://www.csis.org/analysis/updated-report-chinese-strategy-and-military-forces-2021, 146-50.

- A fully capable Northern Theater Command able to plan and execute integrated joint operations into and around the Korean Peninsula, supported by national cyber, space, and airborne surveillance assets

- Anti-ship ballistic missile, air, and submarine capability to effectively threaten US and allied ships, including surface action, amphibious, and carrier groups, in the waters surrounding the Korean Peninsula36US Office of the Secretary of Defense, Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China, 61.

- Cyber and informational influence capabilities with extensive access into South Korean and US civilian and commercial unclassified networks, and even a significant ability to disrupt secure military networks37Ibid., VII.

Though there was consensus on the above points, a key area of some debate is whether the PRC would, in the next five years, be able to fully execute command and control and logistical support to simultaneous major joint military operations in multiple theaters—i.e., operations under the Eastern and Southern Theater Commands including Taiwan and the South China Sea, respectively, along with the Northern Theater Command including the Yellow (West) Sea and Korean Peninsula. This has major implications for China’s options. For the purposes of this study, we assessed that the PRC would have the capability to fight a “two-front war” but would not seek one.38For further analysis on the potential for a two-front war in East Asia, please see Markus Garlauskas, “The United States and Its Allies Must Be Ready to Deter a Two-Front War and Nuclear Attacks in East Asia,” Atlantic Council, August 16, 2023, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/report/the-united-states-and-its-allies-must-be-ready-to-deter-a-two-front-war-and-nuclear-attacks-in-east-asia/.

We also considered the PRC’s economic leverage. We concluded that the PRC would continue to have a high degree of economic leverage over Pyongyang as its primary trading partner. However, we assessed that this would not be decisive in controlling North Korea’s behavior, only enough to imbue some caution into Pyongyang’s calculus toward extreme actions that might have a major effect on PRC interests—at least without a pretext that would resonate in Beijing. The PRC’s economic leverage over North Korea may also be tempered if cooperation between Kim and Russian President Vladimir Putin continues to increase, though this relationship is still far from certain.39David Pierson, “Putin and Kim’s Embrace May Place Xi in a Bind,” New York Times, September 16, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/16/world/asia/china-putin-kim.html. Additionally, we assessed, based on history and statements from PRC officials, that Beijing would be reluctant to dramatically raise the pressure on Pyongyang due to the risk of destabilizing the regime, damaging the already-fragile relationship, or “backing Kim into a corner.”40Kristine Lee, Daniel Kilman, and Joshua Fitt, Crossed Wires: Recalibrating Engagement with North Korea for an Era of Competition with China, Center for a New American Security, December 18, 2019, https://www.cnas.org/publications/reports/crossed-wires; Ben Frohman, Emma Rafaelof, and Alexis Dale-Huang, The China-North Korea Strategic Rift: Background and Implications for the United States, Staff Research Report, U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, January 24, 2022, https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/2022-01/China-North_Korea_Strategic_Rift.pdf.

In contrast, the future of the PRC’s significant economic leverage over South Korea is less clear.41For analysis of China’s economic leverage over the Korean Peninsula, see Lee, Kilman, and Fitt, Crossed Wires; Seong Hyeon Choi, “Why Is South Korea Hesitant to Boycott the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics?” The Diplomat, January 20, 2022, https://thediplomat.com/2022/01/why-is-south-korea-hesitant-to-boycott-the-2022-beijing-winter-olympics/. The South Korean government and some ROK businesses have sought to reduce their reliance on trade with the PRC to decrease their vulnerability to PRC coercion.42Kenichi Yamada, “South Korean Companies Shift Production out of China,” Nikkei Asia, June 22, 2019, https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/Business-trends/South-Korean-companies-shift-production-out-of-China. This intensified in the aftermath of Beijing’s economic punishment of South Korean businesses in retaliation for Seoul’s decision to host a US Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) battery over Beijing’s objections.43For analysis of the THAAD dispute, see Darren J. Lim, “Chinese Economic Coercion during the THAAD Dispute,” The Asan Forum, December 28, 2019, https://theasanforum.org/chinese-economic-coercion-during-the-thaad-dispute/; Ji-Young Lee, The Geopolitics of South Korea-China Relations, RAND Corporation, 2020, https://www.rand.org/pubs/perspectives/PEA524-1.html. Recent trade data reveal a shift in South Korean exports that suggests the beginning of a gradual economic decoupling from the PRC; from 2021 to 2022, South Korean goods exports to the PRC dropped by nearly 10 percent, while goods exports to the United States rose by more than 20 percent, marking the first year in almost two decades that South Korea had exported more goods to the United States than to the PRC.44Christian Davies, “US Overtakes China as Market for South Korean Goods,” Financial Times, June 22, 2023, https://www.ft.com/content/8073cd37-bbf1-46f0-ad31-43ef88283393. Even so, the PRC is likely to remain a primary trading partner of South Korea, given the size of the PRC market, the PRC’s proximity, and many South Korean companies’ reliance on lower-cost PRC labor and materials to maintain their profit margins. Therefore, we assessed that the PRC could still exert powerful economic leverage over South Korea in the next ten years, though this might not—as in the case of THAAD—sway Seoul’s final decisions on core issues of national security.

Given these assessments, the utility of military options in shaping the evolution of a Korea crisis to serve the PRC’s interests would likely equal or surpass that of its economic leverage in the next five to ten years. However, even with both its military and economic power, Beijing is unlikely to be able to simply dictate the outcome rather than influence it. Therefore, we assessed that, in the absence of a direct US-PRC military conflict, the PRC’s initial overall goals in a Korea crisis would likely remain conservative—to avoid instability, war, or nuclear weapons use on the Korean Peninsula, consistent with its past stated goals.45“Xi Says China Ready to Work with DPRK to Preserve Peace on Korean Peninsula,” Xinhua News, March 22, 2021, http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2021-03/22/c_139827776.htm. As a result, we concluded that it is unlikely the PRC will intentionally encourage North Korean military escalation, even if it may unintentionally do so. Instead, the PRC would probably seek to restrain such escalation where possible without putting other regional and global interests at risk, destabilizing North Korea, or causing a break with Pyongyang.

However, we also assessed that these considerations are not the only ones that would motivate Beijing in a crisis scenario in the next decade. As PRC capabilities increase and US-PRC rivalry concerns move to the forefront (particularly due to a looming US-PRC confrontation over the future of Taiwan), Beijing will almost certainly pursue a more assertive policy on Korea issues. Over the long term, we judge that the PRC will seek to end or minimize both the US military presence in South Korea and the ROK-US alliance. Beijing could attempt to use a crisis to advance this goal. In addition, as a crisis evolves and the potential rises for the Kim regime or even the North Korean state itself to fall, other considerations will probably come to the forefront for Beijing. We assessed that the PRC would seek to prevent the establishment of ROK-US military control over North Korea, and of a unified Korean state that would host US forces or be more inclined to choose Washington over Beijing as a security partner. This leads to important judgments:

- The PRC will be increasingly inclined and able to posture forces in response to US and/or allied military actions, particularly in/near the Yellow (West) Sea where it has a clear advantage, possibly escalation dominance.

- The PRC will be willing and able to credibly threaten military intervention, beyond exerting diplomatic and economic pressure, in a Korea crisis if Beijing perceives that its interests are not being sufficiently addressed.

- The PRC is willing to risk war to prevent or block a South Korean-US counter-offensive into North Korea taking place without its consent—such consent is very unlikely to be given for a major ground counter-offensive into North Korea or another operation that appears to move toward regime change or Korean unification.

These judgments, taken together, mean that a major military crisis with North Korea holds a significant risk of either strategic deterrence failure or of a major strategic setback for the ROK-US alliance. A PRC military intervention could result in large-scale combat between PRC forces and US and/or ROK forces if South Korea and the United States move forward with robust military responses to North Korean aggression. Alternately, if Seoul and Washington were to hesitate in the face of threatened intervention or tolerate it, this could reinforce the impunity of the Kim regime and leave Beijing in a stronger position of influence over the future of the peninsula. A cooperative intervention among the PRC, South Korea, and United States (possibly with others under a UN flag) instead is favored by some experts, but these three states appear unlikely to be able to achieve the level of trilateral trust necessary for such a cooperative intervention in the next five to ten years. Ultimately, this more optimistic scenario would require a diplomatic success outside the scope of this analysis.

US and allied strategic deterrence posture in Korea

Given the intertwining of US and South Korean military postures in Korea, along with the established processes and norms of alliance coordination that typically prevail when Pyongyang escalates, the deterrence postures of the United States and South Korea must be considered simultaneously and holistically. Analysis of deterrence in Korea must also recognize that US leaders no longer have the dominant role in determining a South Korean-US response to North Korean escalation, nor are there even many US unilateral military options, short of strategic strikes, that are truly independent of South Korea.

Unlike in decades past, South Korea possesses the vast majority of the alliance’s conventional military capability available to respond to North Korean escalation in a timely manner—including the capability to unilaterally escalate to attempt massive conventional missile strikes against North Korea’s strategic deterrence forces and leadership. Most of these capabilities will advance further in the coming decade, particularly with further development of a new ROK Strategic Command slated for initial establishment in 2024.46Clint Work, ”Navigating South Korea‘s Plan for Preemption,“ War on the Rocks, June 9, 2023,

https://warontherocks.com/2023/06/south-koreas-plan-for-preemption/. South Korea also has the lead for dealing with limited North Korean military escalation on or around the peninsula, at least until strategic deterrence is failing. As a result, several experts we consulted with posited that the United States is more likely to mitigate many of the risks to strategic deterrence indirectly rather than directly, by helping shape South Korea’s future policies, plans, capabilities, or crisis responses.

This means that military preparation for or a response to North Korean escalation could be at the mercy of the perceptions (or misperceptions) and priorities of ROK political officials, or even South Korean domestic political sentiment. South Korean unwillingness to align with the US assessment, or to concur with US proposals, could stymie even the best-considered approaches. Innovations such as the US-ROK Nuclear Consultative Group are a step in the right direction in terms of strengthening mechanisms for cooperative analysis and policy coordination on deterrence. However, given how little “skin in the game,” continuity, and expertise the United States has on some of the key issues, ROK officials may be far better positioned to calibrate some key deterrence efforts than their well-meaning US counterparts.

Our research also found that domestic and organizational political inertia prevailing in South Korea, the United States, and bilateral ROK-US alliance institutions themselves can override realistic appraisals of risks posed by North Korean escalation, particularly years from now. This inertia generally engenders cautious, incremental changes, focused on reassuring South Koreans rather than deterring Pyongyang, which could cause the alliance to fall behind the developing situation over the next decade. In some cases, inertia instead leads to retention of destabilizing approaches and messaging counterproductive to preventing a strategic deterrence failure—as in the continuing insistence by some ROK officials on preparing to conduct preemptive strikes, despite the practical difficulties of pre-emption and the risk that such threats would induce Pyongyang to strike first.47Jeongmin Kim, “Yoon Suk-yeol Backs ‘Preemptive Strike’ to Stop North Korean Hypersonic Attacks,” NK News, January 11, 2022, https://www.nknews.org/2022/01/yoon-suk-yeol-backs-preemptive-strike-to-stop-north-korean-hypersonic-attacks/. Similarly, South Korea’s continued emphasis on preparing retaliatory responses against North Korean leadership targets could either be taken by Pyongyang as a bluff, or could lead to uncontrolled escalation if carried out.48“S. Korea Renames ‘Three-Axis’ Defense System amid Peace Efforts,” Yonhap News Agency, January 10, 2019, https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20190110014000315.

Taking all this into account, the study’s initial findings were derived from a baseline that assumed continuation of US and ROK plans, policies, doctrine, acquisition timelines, and strategies currently slated for implementation in the next five to ten years, or those already in place. As the study was designed to develop actionable recommendations to address the risk of strategic deterrence failure, the analysis remained open to the possibility of major changes from the baseline in the years ahead if recommendations are adopted.

With the looming challenges to strategic deterrence the study identified, many of its most important actionable recommendations would require changes substantial enough to incur significant political or economic costs for Seoul or Washington. When vetting and shaping such recommendations, we ensured they would be technologically, financially, legally, politically, and operationally plausible provided the political will existed at the executive level to pursue such a change over several years. However, experience suggests that pushback against even modest recommendations could be formidable, particularly if they are pursued before North Korean escalation forces an issue to the forefront and provides urgent justification for change. Fortunately, South Korean and US decision-makers could justify changes by highlighting limited escalatory actions such as North Korea’s record-breaking levels of missile testing throughout 2022 and continuing through 2023.49Chad De Guzman, “North Korea Keeps Launching Missile Tests. How Worried Should We Be?” TIME, September 13, 2023, https://time.com/6266737/north-korea-ballistic-missile-tests-2023/.

As detailed in the “Key Findings and Recommendations” section, one of the study’s key findings is that the ROK-US alliance’s military posture—including authorities, capabilities, command relationships, disposition of forces and bases, training, and logistics—was not designed to deal with the present threat, and is unsuited to face the challenges to strategic deterrence in Korea as they are likely to evolve over the next ten years.

First, and foundationally, the alliance’s military command structure is still hamstrung by mechanisms established in another era; founded in 1978 with the establishment of ROK-US Combined Forces Command (CFC), it was modified by the 1994 transition of operational control (OPCON) of all South Korean forces during non-wartime conditions to the ROK Joint Chiefs of Staff (ROK JCS).50For a brief history of the CFC, see “Combined Forces Command,” United States Forces Korea, n.d., https://www.usfk.mil/About/Combined-Forces-Command/, accessed January 2022. Since 1994, CFC, a combined (binational ROK-US) staff headed by a US four-star general, has had a circumscribed role confined to training exercises and planning, without operational control of forces—its day-to-day role is primarily to prepare to control the alliance’s military operations in a full-scale (conventional) war. This bifurcation between CFC and ROK JCS, an arrangement whose shortcomings may have been manageable for decades, is likely to leave the alliance badly served in a range of scenarios. This will even remain the case if the ongoing transition of OPCON is completed as planned and a South Korean officer leads the combined headquarters.51For more information on OPCON transition, see Sean Creamer, “Setting the Record Straight on OPCON Transition in the U.S.-ROK Alliance,” National Bureau of Asian Research, July 16, 2021, https://www.nbr.org/publication/setting-the-record-straight-on-opcon-transition-in-the-u-s-rok-alliance/. Because of this system, there is not a clear mechanism for commanding and controlling joint combined operations of ROK-US forces in a limited conflict, while neither arrangement suits a conflict that goes nuclear. Participants described this phenomenon as a “light switch” with only two settings or “having only a five-dollar or a hundred-dollar bill.”52The second quote is from a serving US military officer who credits then-Chief of Staff of the Army General Peter Schoomaker as having coined this metaphor in a different but related context.

This light-switch paradigm of wartime or peacetime is problematic. Study participants argued that US deterrence efforts in and around Korea should not rely on capabilities that are not either already in the area, or able to visibly project power from their normal operational or base areas well away from the peninsula. Any one of three key factors could be sufficient to delay or prevent movement of additional key capabilities to Korea during a crisis in time to make a difference:

- The political imperative to avoid the perception of transitioning to a war footing

- The practical challenges of quickly deploying additional combat power over long distances

- The risk of pushing Pyongyang into a “preemptive” mindset

One study participant noted: “When it comes to a crisis on the [Korean] Peninsula, you’ve got what you’ve got. Once the crisis starts, reinforcing USFK (United States Forces Korea) to strengthen strategic deterrence is just not realistic. The reinforcements will come only after it’s clear that strategic deterrence has failed and we’re going to war!” This suggests that most off-peninsula US military assets could be useful for deterrence by punishment approaches at best. Such use still would require Washington to convince Pyongyang that the United States has the political will to bring in forces to fight a war if North Korea escalates beyond a certain level—and would require Seoul to go along.

The study concluded that USFK’s force posture as it exists today is largely a legacy of choices made decades ago and has little to do with today’s requirements for strategic deterrence of North Korea—it is not a posture designed “from the ground up.” An example of a choice that has complicated strategic deterrence is the decision to enable large numbers of US noncombatant family members to accompany service members to live on and around US military bases. Their presence enables longer overseas tours, thereby signaling sustained US commitment, seemingly reinforcing deterrence of North Korea and reassurance of South Korea. However, these civilians would be a liability in an escalating crisis, putting USFK in a position where military family members could be virtual hostages to the threat of North Korean military action. Meanwhile, a noncombatant evacuation operation in Korea has come to be seen by both North and South Koreans as a clear signal that the United States plans imminent strikes. Such an evacuation could tip North Korea into a preemptive mindset while triggering economic disruptions and panic in South Korea, straining the alliance in a crisis—even if Seoul could be convinced that the United States would not strike unilaterally.

Similarly, the decision to concentrate the US basing footprint in South Korea from a scattering of bases, many of them in populated areas in or north of Seoul, into new facilities in larger bases well south of Seoul, like Camp Humphreys, was designed to enable efficiencies, longer tours, and a better quality of life.53See Hyung-jin Kim and Tong-hyung Kim, “US Ends 70 Years of Military Presence in S. Korean Capital,” AP News, June 29, 2018, https://apnews.com/article/d85519e00e5042739e0fde2fdb295bc8. However, these large groupings provide North Korea the opportunity to fire missiles at key US bases with minimal risk to civilian structures as collateral damage. Deterrence theory suggests such military concentrations are also tempting targets for preemptive nuclear strikes.

Lastly—and perhaps most problematically from a strategic perspective—the alliance’s strategic and operational posture has generally steered away from deterring the PRC militarily or embracing more multilateral approaches to deterrence. Most experts we spoke with believed that this was due primarily to South Korea’s overriding domestic concerns about the economic costs of antagonizing Beijing and suspicion of being drawn into an “anti-China” military coalition. Some, however, noted that the “division of labor” between USFK and US Indo-Pacific Command (INDOPACOM), wherein USFK focuses on North Korea and INDOPACOM on the PRC, was a primary factor leading to organizational stove-piping that obstructs a more realistic and holistic approach to countering the future PRC challenge around Korea.

Synthesis and Conclusion: Rising Risks for Strategic Deterrence

Based on this analysis, the risk of strategic deterrence failure stemming from a crisis initiated by North Korean escalation will increase dramatically in the next ten years if North Korean, PRC, South Korean, and US capabilities and intentions continue to develop along their current trajectories. Given expected growth in North Korean capabilities, there are three key trends that that current US and South Korean approaches appear unlikely to counteract:

- As North Korea develops improved capabilities for precise limited strikes—such as more accurate missiles capable of evading missile defenses to strike military targets with minimal risk of civilian casualties—Pyongyang is more likely to believe limited escalation could succeed without triggering regime-threatening responses.54Markus Garlauskas, “The Evolving North Korean Threat Requires an Evolving Alliance,” in The Future of the US-ROK Alliance, Atlantic Council, February 2021, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Chapter-4.pdf.

- The increasing credibility of North Korea’s second-strike nuclear deterrent, particularly its growing capability to reach the contiguous United States (CONUS), will raise the level to which Pyongyang believes it can escalate while minimizing retaliation, by forcing the alliance to choose between a small-scale response or risking full-scale nuclear war.

- As North Korea’s tactical nuclear capabilities increase and diversify, this raises the probability that North Korea will see viable options for very limited nuclear use that could help achieve the regime’s politico-military objectives in a high-stakes conflict or confrontation—without necessarily triggering regime-ending retaliation.55For an example of limited military conflict initiated by North Korea, see Markus Garlauskas, “North Korea’s Arena of Asymmetric Advantage: Why We Should Prepare for a Crisis in the Yellow Sea,” CNA, October 2021, https://www.cna.org/CNA_files/PDF/North-Koreas-Arena-of-Asymmetric-Advantage-Why-We-Should-Prepare-for-a-Crisis-in-the-Yellow-Sea.pdf.

The increasing risk to strategic deterrence posed by these trends will be heightened by their potential to “stack” upon each other, and the direct and indirect threats that PRC actions could pose for strategic deterrence failure will further exacerbate this risk. In addition to the risks to strategic deterrence presented by direct PRC intervention, as noted previously, the PRC’s capabilities and likely behavior could unintentionally encourage Pyongyang to escalate in a crisis. Though we assessed that Beijing would try to restrain North Korean escalation—other than in scenarios outside the scope of this study—the effect of PRC efforts to restrain the escalation of a crisis could have the opposite effect.

Greater potential for PRC involvement could encourage Pyongyang to believe that Washington and Seoul will hesitate due to fear of a military response from Beijing. As the credibility of PRC nuclear and conventional military capability increases, Pyongyang will probably believe it can escalate further while minimizing the risk of unacceptable US or South Korean retaliation. Generally, the PRC is likely to affect Pyongyang’s escalation calculus in the following ways:

- As the US-PRC rivalry becomes the dominant strategic lens in Beijing and Washington, the potential that North Korea will see opportunities to play one off against the other and Seoul will increase. In the event of an escalating PRC-US confrontation or conflict sparked by other issues, this potential is heightened.

- As PRC capability and apparent intent to intervene increases, Pyongyang will judge it increasingly unlikely that Seoul and Washington would take the risk of either a major ground offensive into North Korea, or of strikes intended to destabilize or decapitate the North Korean regime—as either could trigger a PRC intervention.

- In this strategic context, as North Korea develops a wider range of more precise and more effective non-nuclear military options for limited attacks in the next decade, Pyongyang is also more likely to see options to escalate without meaningful PRC punishment as Beijing dissuades a strong reaction from Seoul or Washington.

These phenomena could also have a mutually reinforcing effect that tilts Pyongyang’s calculus toward perceiving that it could escalate further with lower risk of retaliation. All these phenomena, however, are contingent upon Beijing proving unable to meaningfully change Pyongyang’s perceptions. Beijing’s past difficulties in influencing Pyongyang’s calculus suggests this would be challenging, but not necessarily impossible.

Conversely, if Beijing breaks from its past patterns, and dramatically raises the pressure on Pyongyang to the point where it appears that Beijing is willing to see the fall of the Kim regime, this is likely to put North Korea into a “nothing to lose” mindset where the logic of using nuclear weapons first would be compelling. When examined from this perspective, Beijing’s past logic in showing restraint toward Pyongyang, though often frustrating from the perspective of Washington, is understandable and may even be desirable for strategic deterrence.

Key findings and recommendations

Finding: Of all the potential scenarios for strategic deterrence failure in the next decade, Pyongyang seizing an opportunity to launch a full-scale attack to reunify the Korean Peninsula is one of the least plausible. The path toward strategic deterrence failure is far more likely to begin with limited North Korean coercive escalation. Such coercion could lead to an escalation cycle fueled by limited South Korean or US responses that lead Pyongyang to escalate further to retake the initiative, which would then drive escalation dynamics that trigger North Korea to launch a preemptive or preventive attack and motivate Beijing to intervene.

With this in mind, the study identified three potential mindsets in Pyongyang that could lead to North Korean escalation, each with distinct deterrence implications. To prevent strategic deterrence failure, ROK-US deterrence efforts should deter North Korean escalation without pushing Pyongyang to the third and highest-risk category of mindset. These three levels include the following:

1) “Exploit opportunity”—North Korea perceives itself to be in control of the situation, escalating for advantage (relatively low risk acceptance)

2) “Retake initiative”—North Korea perceives it is losing control of the situation, feels threatened, and escalates seeking to gain control of the situation (increasing risk acceptance, “sense of urgency”)

3) “Preempt/prevent”—North Korea perceives that an external threat of potential regime-ending scope is unavoidable and/or imminent, so escalates intensely and preemptively or preventively (high risk tolerance, “nothing to lose”)

- Recommendation: The US government, working closely with ROK counterparts, should change the alliance’s public messaging and guidance to relevant military commands to strongly favor deterrence by denial approaches and reduce reliance on deterrence by punishment approaches. The goal of this change should be to undermine North Korea’s confidence in escalatory options without further threatening the regime. To enable this, the US and South Korean militaries should place a renewed emphasis on showing capability and confidence to absorb a North Korean attack, respond proportionally, and win. This would include improving and demonstrating active and passive missile defenses, as well as visibly training for resilience in the face of a missile attack. US leaders should strictly avoid messaging or actions even suggesting that preemption or “decapitation strikes” are part of alliance thinking and ask South Korea to follow suit.

- Recommendation: The United States should develop and propose new offers of defense crisis management and transparency systems to North Korea—although these are typically rebuffed—in an effort to reduce the risks of miscalculation leading to a preventive or preemptive attack by North Korea. To enable this approach, the US government should grant greater authorities to United Nations Command (UNC) and USFK to pursue military-to-military engagement with North Korea. These mechanisms should build upon, rather than attempt to replace, the armistice maintenance mechanisms with new military-to-military channels. Absent new authorities, UNC should work to preserve and enhance crisis management mechanisms between the UNC Military Armistice Commission (UNCMAC) and North Korean counterparts. UNC should also work closely with US and ROK officials to maximize US and ROK governments’ understanding and use of existing crisis management mechanisms, including the military hotline, the “General Officer Talks” forum, and UNCMAC investigations of armistice violations.

- Recommendation: The US defense community and military commands with responsibilities relating to Korea should pursue the study, development, and execution of approaches to achieve subnational deterrence effects on North Korea, including targeted influence of mid-level actors, to delay or prevent escalatory moves or overreactions by subordinates to Kim Jong Un that may fuel escalation dynamics. The US government should sponsor additional analytic work on the concept of subnational deterrence, which is summarized in Appendix A.

- Recommendation: The US government should sponsor and conduct studies, analysis, and gaming on the effects of North Korean domestic instability dynamics on escalatory decision-making since this issue is potentially key for strategic deterrence but was outside the study’s scope.

Finding: A combination of more precise and capable conventional options for North Korea with a more robust second-strike nuclear deterrent will challenge the credibility of US deterrence by punishment over the next five to ten years, increasing the level to which North Korea believes it can escalate without triggering a regime-ending response. As Pyongyang grows more confident in its own nuclear deterrent and in the likelihood of assertive PRC involvement in Korea to counter its strategic rival, the United States, Pyongyang’s perceived viable escalatory options to either press its advantage or retake the initiative will increase in intensity and diversity.

- Recommendation: The ROK-US Security Consultative Meeting (Ministerial-level) and Military Committee (4-star level) alliance coordination mechanisms should work together to provide guidance and structures that will enhance the alliance’s ability to conduct a “quick, combined, and calibrated” ROK-US response to limited North Korean aggression to enhance deterrence by denial. This should include the publicly announced development of a combined (ROK-US) and joint task force with the mission of preparing to command and control a short-notice ROK-US alliance military operation to respond to North Korean aggression in scenarios short of war but beyond a small-scale ROK self-defense response. Such a response probably holds the best chance of convincing Pyongyang that further escalation will not shake the ROK-US alliance’s resolve or unity and will not achieve any military advantage, while being sufficiently restrained to send a clear assurance that a regime-ending ROK or US attack will not be forthcoming if Pyongyang shows restraint. The study’s research suggests that it would be very difficult to achieve this balance with military responses that are slow, unilateral, and/or not calibrated carefully to fall within a relatively narrow range on the escalatory “ladder.”

- Recommendation: The US government should allocate resources and provide guidance to help USFK enhance its force posture, capabilities, and training to stay ahead of growing North Korean capabilities and improve deterrence by denial. This should include deployment, and then permanent stationing of reinforced missile defenses, anti-rocket systems, and anti-unmanned aerial vehicle (anti-UAV) systems for all US bases in Korea, including the deployment of an existing US Iron Dome battery and a follow-on system produced under the Indirect Fires Protection Capability (IFPC) Program, currently in development . USFK, CFC, and South Korean military training should emphasize resiliency, hardening, and dispersion against North Korean missiles, and emphasize such training in public messaging.

- Recommendation: The United States government should seek an agreement with South Korea for standing integration of USFK missile defense assets and sensors into a combined air and missile defense architecture to reinforce deterrence by denial of North Korean missile attacks. To respect political sensitivities, this could be designed as integrating USFK assets into an on-peninsula-only structure, with a South Korean commander in the overall lead, rather than integrating ROK systems into a US-led regional architecture. In implementing this recommendation, preference should be given to using ROK systems to engage incoming missiles in situations short of war where US bases are not firing in self-defense.

- Recommendation: The US government should ensure that continued investment in national missile defense denies Pyongyang the capability to reliably and credibly threaten the US homeland with second-strike nuclear capability despite expansion in numbers of North Korea’s ICBM force and enhancements to its missile defense evasion capability.

Finding: The likelihood of PRC intervention and interference in a Korea crisis will increase in the coming decade, as PRC military capabilities grow and the PRC-US strategic rivalry heightens. The ROK-US alliance is not yet politically or militarily postured to deter or defeat a PRC intervention, and both partners seem unwilling to pay the political costs to confront this growing challenge more directly. This is likely to encourage North Korean adventurism and complicate ROK-US deterrent responses, particularly in the Yellow (West) Sea near China.

- Recommendation: CFC and USFK, with the full support of the US government, should shift from an explicit focus only on North Korea to a broader focus on protecting South Korea from aggression. This should encompass deterrence of the PRC and preparations to defeat a PRC intervention without necessarily explicitly stating the PRC in the commands’ mission statements. This should be maintained by any new combined ROK-US headquarters, if one replaces CFC. US officials should work closely with ROK counterparts to ensure that South Korea supports this shift, and to avoid any perception that this is an effort to pull the Seoul into a confrontation with Beijing.

- Recommendation: The DOD and the US Joint Chiefs of Staff should undertake a comprehensive re-look at US command and control relationships in Northeast Asia to address potential PRC threats in and around Korea, particularly in the Yellow (West) Sea. At a minimum, the study should consider the pros and cons of reviving a separate Far East Command, expanding USFK’s role and area of responsibility within INDOPACOM, and establishing or adjusting subordinate commands or task forces within INDOPACOM.

- Recommendation: INDOPACOM, in close coordination with UNC, CFC, and USFK, should seek more multilateral (such as Australian, United Kingdom, or Canadian) rotational contributions of aircraft and maritime patrols or exercises around or near South Korea to reinforce the international commitment to defense and deterrence against threats to South Korea. This should be part of a comprehensive approach directed by the White House and Pentagon and led by INDOPACOM, to “internationalize” responses to and deterrence of escalation against the ROK in a way that transcends US-PRC strategic competition. This should build upon multilateral efforts to monitor North Korean maritime sanctions evasion with military assets already being coordinated by the US 7th Fleet; due to political obstacles and sensitivities, it should not simply be an expansion of the UNC mission.

- Recommendation: CFC and USFK, in coordination with INDOPACOM, the Pentagon, and South Korean counterparts, should develop and practice scalable military options to expand US military presence and operations in the Yellow (West) Sea and Northwest Islands area in support of the ROK Northwest Islands Defense Command or of an alternative ROK, US, or ROK-US military command. These options would be designed to both increase deterrence and limited response options against a North Korean attack there, as well as discourage PRC intervention in this area. Such options should include a standing rotational presence of US special operations or other appropriate personnel on the Northwest Islands, capable of calling for standoff precision fires against North Korean—and PRC, if necessary—forces threatening ROK-US forces and personnel in this area. UNC should also explore options to establish and maintain a rotation of non-ROK and non-US observers on the Northwest Islands from UN Sending States.

- Recommendation: US and South Korean organizations should sponsor and conduct additional studies and wargaming on the potential for the PRC to intentionally seek a confrontation around Korea as part of a larger conflict, such as one over Taiwan. The US government should direct additional research and gaming resources to support such an effort.

Finding: The ROK-US alliance military posture (including authorities, capabilities, command structure, readiness, and training) has not been designed for the full spectrum of conflict from limited provocations to nuclear war, and is not on a path to change in the next ten years. This posture is designed almost exclusively for two possibilities: ROK self-defense against small-scale “provocation” by North Korea or a deliberate transition to combined ROK-US war operations in a large conventional war with North Korea. This posture is unsuited for a rapid, but limited, response to an attack short of full-scale war. It is also unsuited for deterring or defeating PRC intervention, or for fighting a war that includes nuclear strikes—all possibilities that the United States and its allies should prepare for.

- Recommendation: The US government should work with ROK counterparts and CFC to finally complete the long-delayed transition to a new ROK-US “wartime” OPCON structure to avoid a continued focus on preparing for OPCON transition, distracting from the requirements of reinforcing deterrence. As part of completing this transition, a new post-transition combined ROK-US headquarters should be empowered with the authorities and capabilities to command and control a limited ROK-US combined operational military response by a subset of ROK-US forces in conditions short of a “full wartime” situation. This would help “deter by denial” limited North Korean aggression beyond a localized incident by making it clear that South Korea and the United States could respond together to a limited attack and would not be forced into choosing a unilateral ROK response or taking the risk of transitioning to a war footing. This would also support aforementioned recommendations by enabling a “quick, combined, and calibrated” military response to limited North Korean aggression.

- Recommendation: The US government should ensure that sufficient numbers of new Precision Strike Missiles and similar weapons are delivered to USFK as soon as they are available to replace the aging Army Tactical Missile System. These missiles would help enable rapid and effective conventional precision strikes by USFK elements within a combined response to North Korean aggression, without requiring escalation to destruction of North Korean air defenses or deployment of additional assets from off-peninsula. They would also provide a US capability parallel to the land-based missiles with similar ranges that South Korea already has. Given the political sensitivities of deploying new missiles to South Korea, and likely objections from Beijing, political preparations for such deployments should start now.

- Recommendation: DOD organizations with nuclear warfighting and consequence management roles should expand their forward presence in South Korea and their partnerships with CFC and the ROK military to ensure that ROK forces and CFC are intellectually and operationally better prepared for a conflict with North Korea that involves nuclear use. A central premise of this effort should be helping to ensure that ROK forces have the confidence to fight and win even if North Korea engages in limited nuclear weapons employment to help reinforce deterrence by denial and reduce reliance on US deterrence by punishment with nuclear weapons.

- Recommendation: The United States should expand its comprehensive engagement with South Korea on force development, modernization, and defense technology cooperation. This would be designed to help inform a more holistic ROK-US approach to capability development and fielding for after OPCON transition, well beyond the scope and time frame of the existing Conditions-based Operational Control Transition Plan. This would help enable the development of ROK-US capabilities and approaches that would better position the alliance to deal with deterrence challenges from North Korea and the PRC in the coming decades.

Finding: Pyongyang’s regime almost certainly knows it cannot survive if it triggers an all-out nuclear exchange, but it will probably see greater viability for limited nuclear use in the next five to ten years. If North Korea were to employ a nuclear weapon, it would most likely be in a limited manner intended to pose a dilemma for and constrain the ROK-US (and PRC) response. North Korea’s increasing capability to conduct a limited nuclear “demonstration” or tactical strike will give North Korea options that could undermine US extended deterrence globally, even if the immediate US response to such use prevents a catastrophic near-term strategic deterrence failure.