Democracy, dealmaking, and stability: Rethinking US engagement in Africa

Bottom lines up front

- The United States is reevaluating democracy assistance in Africa at a time when democratic institutions, citizen aspirations, and regional stability depend on sustained support for accountable governance.

- Strengthening democratic pathways, empowering citizens in democratic and authoritarian contexts, and investing in stabilization and local peacebuilding are essential to protecting African progress and advancing US interests.

- Private philanthropy and the private sector must play a larger role in sustaining electoral integrity, supporting civil society, and fostering conditions that enable long-term democratic and economic gains.

This issue brief is part of the Freedom and Prosperity Center’s “The future of democracy assistance” series, which analyzes the many complex challenges to democracy around the world and highlights actionable policies that promote democratic governance.

Introduction

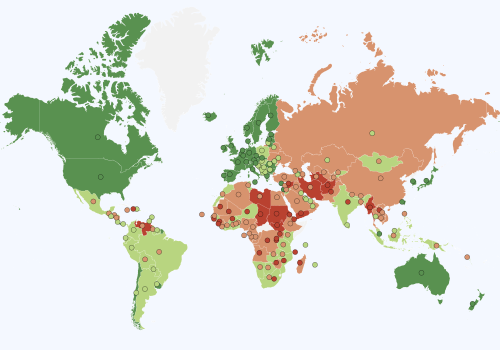

The political landscape in Africa defies generalization. Despite setbacks and challenges, democratic progress continues in Ghana, Malawi, and Senegal, among other countries. Next to these bright spots, military juntas have deepened their grip on multiple West African and Sahelian governments, long-standing authoritarian regimes remain in Rwanda, Uganda, and other countries, and conflict and war continues to upend lives and threaten the territorial integrity of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Sudan. Numerous other countries are best described as hybrid regimes, combining democratic and authoritarian forms of governance and producing inconsistent outcomes for their citizens in terms of delivering public goods, securing basic rights, and promoting economic growth.

Against this backdrop, the United States is recasting its relationship with African governments and their constituencies. Department of State officials describe “trade, not aid” as the foundation of US policy in Africa. In doing so, they have named expanded access to critical minerals and energy resources, alongside the development of new markets for US exports, as signature priorities for the Trump administration on the continent. This shift has brought cascading effects on African nations. As the region with the largest historic inflow of US foreign assistance, deep and sudden cuts to the aid budgets of the US Department of State and the closure of the US Agency for International Development have disproportionately affected African countries.[2]

Previous US administrations—including the first Trump administration—promoted democratic governance and stability in Africa using a combination of diplomatic and development tools. In fiscal year 2023, for example, the US government spent more than $338 million on democracy, human rights, and governance (DRG) programming in Africa. Even more was spent in the final year of the first Trump administration, when DRG spending in Africa stood at more than $415 million.

Today, the outlook is very different. In addition to eliminating most democracy assistance to the continent in the early round of aid cuts, the administration has sought to defund the National Endowment for Democracy and proposed the elimination of nearly all DRG funds in its 2026 budget. Meanwhile, it has shifted away from criticizing foreign governments on democratic and human rights grounds.

Regardless of the direction of US government policy, recent history shows that both African societies and US national interests are best served by stable, democratic, and accountable systems of governance, which have proved more effective at delivering peace, expanding socioeconomic opportunity, and fostering market economies that attract domestic and international investment. Given this reality, the “dealmaking” intended to drive the administration’s foreign policy will find its greatest long-term success in countries with stronger and more democratic institutions.

This brief makes recommendations for how and why US stakeholders should work with democratic partners in Africa to seek democracy and stability-related outcomes. It includes specific recommendations directed at the US government for using democracy assistance as a tool to advance key African and American priorities. Recognizing that the near-term reality of reduced funding for US government democracy assistance will generate new shortfalls and challenges, this brief also identifies opportunities for other American institutions, namely private philanthropy and the private sector, to partner with key democratic actors and advance DRG practice in Africa.

Why prioritize democracy, good governance, and stability?

There are numerous practical reasons for the US government and constituencies to prefer and encourage democracy, good governance, and stability in Africa. Most importantly, it is what African publics want. Survey respondents on the continent consistently report a preference for democratic systems of government over all other options. The 2021–23 Afrobarometer survey found that, across thirty-nine surveyed countries, 66 percent of respondents prefer democracy over any other kind of government, while 78 percent oppose one-party rule and 66 percent oppose military rule. Despite some erosion in overall support for democracy over the past decade, popular support for democratic governance remains resilient in the face of social and economic headwinds and global momentum for authoritarian governments.

Despite challenges, democratic and institutionally stable regimes have yielded economic, political, and social benefits. The Atlantic Council’s Freedom and Prosperity Indexes show that globally, while gains often take time to accrue, democratizing countries see an average bump of 8.8 percent in gross national product per capita over a twenty-year period compared to their autocratic peers. Meanwhile, institutional instability and fragility remain especially damaging to socioeconomic well-being. Countries with the highest levels of fragility as defined by the Fragile States Index have seen slow or significantly negative economic growth, conflict, and recurrent humanitarian crises. Insecurity and crisis, in turn, create unstable markets, disrupt supply chains, and erode long-term investment for US industries.

From an American perspective, African countries with stable and democratic institutions have been reliable economic, political, and security partners. They are more inclined to establish and strengthen rules-based economic and political systems that protect US and other investors. In regions like the Sahel, as elaborated on below, democratic governments serve as key political and security allies, while undemocratic and especially unstable countries have invited foreign interference by geopolitical rivals and create risks related to radicalization.

Institutional stability will only become more important as the US government and corporations push to expand trade relations and close deals in capital-intensive sectors like mining. Moving forward, the limiting factor on investments that generate returns for African and American economies alike is not the ability of the US government to sign deals today, but its ability to encourage stable economic and political conditions that protect those investments in the years to come.

Priorities for democracy assistance

A sensible US foreign policy interested in achieving meaningful social, political, and economic gains for African partner societies and US stakeholders alike would make diverse investments in stable, democratic, and accountable governance on the continent. We identify three broad priorities that could power an effective democracy assistance strategy:

- Invest in countries on a democratic pathway.

- Ally with citizens, including in backsliding democracies and autocracies.

- Prioritize stabilization and local institutions that enable peace and security.

These priorities and the specific investments listed below are not meant to be comprehensive, but rather indicative of what a balanced and sufficiently ambitious US democracy assistance strategy could entail. The priorities could be applied across a wide set of countries and regions, or focus on specific geographies where the US government has direct economic and security interests, such as large population centers and economies like Nigeria and Kenya, or strategic regions like the Great Lakes, Horn of Africa, and Sahel. Recognizing that the US government is poised to reduce its investments in critical areas of intervention, we identify specific opportunities for private philanthropy and the private sector to play a leadership role in delivering and reenvisioning elements of a democracy assistance package moving forward.

Priority 1: Invest in countries on a democratic pathway

Reinforcing the economic, political, and security gains to democratic stability in Africa, the United States should continue to invest in the success of aspiring and longer-standing democracies on the continent. Democratic governments are better at protecting the rights and well-being of their citizens while creating hospitable conditions for secure, long-term investments and trade relations. Key democratic governments on the continent have set reform agendas with the potential to benefit their citizens and serve near- and long-term American economic and political interests. Furthermore, multiple democratic countries represent anchor security partners for the United States and critical bulwarks against instability, radicalization, and foreign interference in volatile regions such as the Sahel.

Take Senegal, for example. Senegal provides a case study for how a country that has made long-term democratic progress—and that overcame threats to its 2024 presidential election—is prioritizing economic and governance reforms that are responsive to the stated interests of its citizens. Like other recently elected governments on the continent, Senegal’s administration has prioritized anti-corruption, structural economic reforms, and poverty reduction, among other signature initiatives. Senegal’s President Bassirou Diomaye Faye led this effort by declaring his assets during the election and, once in office, announcing audits of the oil, gas, and mining sectors. The administration similarly proposed multiple transparency laws and released previously unpublished reports from anti-corruption institutions.

The extent and success of reform efforts in Senegal remains to be seen, but they have the potential to strengthen its citizens’ socioeconomic security and overall market economy. Alongside Ghana, Senegal remains a long-standing democratic partner in a region where the proliferation of military-led governments has put US security interests and assets at risk, as evidenced by the recent closure of US military bases in Niger. The U.S., therefore, has a direct stake in the success of governance-strengthening efforts in countries like Senegal.

The US government and other entities should make strategic investments in countries on a democratic pathway, like Senegal, to achieve results in high-priority areas of reform and strengthen key institutions, including in sectors of mutual interest to the US stakeholders and partner governments.

- Prioritize support for reforms that are championed by government partners. External technical and financial assistance is most effective when supporting reform and governance-strengthening initiatives that are owned and led by government partners. Indeed, political commitment alongside bureaucratic capacity are among the interrelated factors contributing to the success or failure of reform. In countries seeking to entrench democratic and economic reforms, the US government can work with partner governments that see their political futures as tied to the success of reforms across a range of economic and social sectors, such as public health, transportation, and financial services where key benefits accrue to US constituencies. The US government can aid these reform efforts by providing technical assistance, technology transfers, and direct financial support, concentrating on sectors where the US has a strategic interest.

- Continue social and capital investments in democratizing countries. The US government has used vehicles such as the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) to invest in economic and social sectors in countries meeting basic governance benchmarks. This has included, for example, using cofinancing models to support upgrades of the energy sector in Senegal and the transport sector in Malawi. The MCC’s investment-led, government-to-government approach is suited to countries on a stable and democratic trajectory, where US and partner country investments are more likely to be secure. While its future remains uncertain, the MCC and institutions like the Development Finance Corporation can help democratizing countries generate capital for high-priority, high-impact sectors that can contribute to economic growth and social welfare. Looking forward, the US government can maintain investments in strategically important countries like Cote d’Ivoire and Zambia. It can also use its investments to crowd in funding to sectors of mutual interest for African and American businesses and other stakeholders.

The role of other actors: Private philanthropy must maintain support for free and fair electoral systems

The integrity of electoral institutions and, ultimately, the conduct of elections has an outsize influence on the trajectory on democratic consolidation. The US government has decades of experience supporting political parties, strengthening the infrastructure for independent election monitoring, and strengthening electoral management bodies (EMBs), which research shows is critically important to democratic trajectories, including re-democratization. Meanwhile, the current Department of State has backed away from electoral assistance programs and issued directives restricting embassies from criticizing foreign elections.

Given trends in US government policy, private philanthropy can help preserve US leadership in international electoral support. While the philanthropic sector cannot replace US government election funding—which included $48.9 million in support for unanticipated events like snap elections across twenty-eight African countries between 2022 and 2024—it can make high-impact investments that help preserve and build on democratic gains. These investments could include, for example, prioritizing targeted support for EMBs and the electoral monitoring capacities in countries working to consolidate their democratic progress.

Priority 2: Ally with citizens, including in backsliding democracies and autocracies

In pursuing a dealmaking-focused foreign policy, it will be tempting for the US government and private sector to “deal” primarily or exclusively with power-wielding political and economic elites. Doing so risks putting the United States at odds with African publics who express a preference for democracy and accountable governance, while potentially promoting corruption and distorting markets key to fair competition for US and other businesses.

Many African societies have tended to hold positive views of the United States and find resonance with its economic and political values. Recent research from Pew found that the some of the highest US approval ratings from foreign publics come from surveyed African countries. These findings mirror older Afrobarometer data showing that preference for the US development model outcompetes China’s by 11 percentage points across surveyed countries. This research suggests that views of the United States are influenced by its perceived commitments to democratic and free-market development approaches.

An effective foreign policy focused on long-term US interests must grapple with the reality that the political and socioeconomic interests of African citizens are not always served by their leaders. Many regimes tilt the electoral system in their favor, effectively silencing their electorates. Across a range of countries, civil society and human rights leaders face political repression for exercising their fundamental political rights. And too many large-scale investments in extractives and other sectors—including investments led by transactional Chinese state and corporate entities—have undermined the human rights and failed to serve the interests of local communities.

Allying with African citizenries does not mean forgoing economic and political dealmaking. Across regime types, citizens want to see expanded economic opportunity, social welfare gains, and security. Failure to prioritize the economic and political needs and interests of African societies, however, would put the United States on the wrong side of many of the youngest populations in the world, jeopardizing hard-won admiration on the continent. Democracy assistance offers practical tools for supporting and protecting key constituencies.

- Invest in strengthened economic governance and business climates. African publics and the US government and corporations have a shared interest in strengthening business sectors that enable fair, rules-based market competition. The US government should invest in strengthened economic governance through targeted support to government and nongovernment actors, potentially focusing on sectors with heightened exposure for the United States. This could, for example, include supporting efforts to reduce child labor and forced labor from supply chains, thereby addressing significant human rights violations and leveling the economic playing field for US corporations that must adhere to international labor standards. Where there is state commitment to reform, the US government can support technical assistance to lawmakers and regulatory bodies to put in place and implement legal, policy, and regulatory frameworks that meet international standards. It can also support chambers of commerce, industry associations, and civil society organizations to promote transparent and accountable business practices and advance market-oriented reforms.

- Prioritize anti-corruption and accountability. Support for anti-corruption efforts by committed government and citizen actors offers a clear opportunity for the US government to stand with African publics. In countries as varied as Gabon, Gambia, Liberia, and South Africa, more than 70 percent of Afrobarometer respondents report that corruption increased “somewhat/a lot” in the past year.” Corruption concerns have helped fueled democratic transitions in countries such as Ghana and Senegal, as well as large-scale protests in Kenya, Madagascar, and South Africa, among others. The US government could assist governments committed to anti-corruption efforts to advance e-governance that has been shown effective at reducing opportunities for corruption. The United States should also support civil society and independent media to conduct investigations, analyze public data, and advocate for public transparency and accountability, including to address regional challenges like cross-border illicit financial flows that harm US economic interests.

The role of other actors: Private philanthropy should prioritize emergency assistance to civil society and human rights institutions

With the near-term decline of the US government’s support to civil society in Africa and globally, private philanthropy is best placed to shore up critical gaps while shifting the terms of assistance for civic institutions. In particular, private foundations can prioritize funding for emergency assistance aimed at protecting individuals and organizations facing acute risks of political repression. The annual value of US government human rights programming in Africa was $21.6 million in fiscal year 2022, of which emergency assistance activities was only a part. The sums involved for sustaining core emergency assistance categories are within the capabilities of individual or coalitions of leading US philanthropies.

Private foundations can also adopt regional or global approaches to directly funding and supporting local civic institutions. This could include developing programs that facilitate horizontal relationships, learning, and mutual assistance among civic actors from Africa, the United States, and other regions grappling with common struggles related to conflict, democracy, and accountable governance in their societies.

Priority 3: Prioritize stabilization and local institutions that enable peace and security

Instability and conflict remain critical challenges across key regions and countries in Africa. The Fragile States Index shows that four out of the five most fragile countries (and sixteen out of the most fragile twenty-five countries) globally are in sub-Saharan Africa. Recent years have seen a rapid expansion in the scope and intensity of conflict in the region. This includes conflicts fueled or amplified by extremist groups in the Sahel, West Africa, and coastal East Africa. It also includes civil conflicts in Ethiopia, Sudan, and South Sudan, among other countries. The human and economic costs of conflict are vast. In 2023, the number of displaced persons in Africa approached 35 million, representing nearly half of the total number of displaced persons globally.

In the DRC and broader Great Lakes region of Africa, the Trump administration has shown a willingness to use its political capital to seek an end to a long-standing and worsening conflict that threatens its trade and investment interests. In late June 2025, the US government announced a peace deal between the DRC and Rwanda governments aimed at halting the conflict between state authorities and the March 23 Movement (M23) rebels. Questions remain about the ultimate effectiveness of the settlement given that M23 and other rebel groups are not direct parties to the agreement. The US government, however, has expressed commitment to its implementation, which it sees as necessary for enhanced American access to critical minerals, including cobalt, copper, and tantalum. As in other countries with active conflicts, the US government has cut important aid programs to the DRC that invest in the social infrastructure and critical institutions necessary for supporting and sustaining peace deals. The long-term durability of any peace, however, depends on empowered individual and institutional structures that can deliver foundational levels of governance, and social and economic benefits that can reinforce stability.

- Maintain support to networks of peacebuilders at the local, regional, and national levels. Integrated networks of formal and informal peacebuilding institutions and individual activists are critical to monitoring, responding to, mitigating, and managing conflict, especially at the local level. Local peacebuilding committees and related structures have a track record of enabling community-level peace outcomes and social cohesion in countries like Burundi, Ethiopia, Ghana, and Kenya. Similarly, mutual aid groups are playing a key role in responding to the impacts of conflict in contemporary Sudan. The US government should prioritize cost-effective investments in the peace institutions and structures that monitor and strengthen peace settlements, especially in countries and regions where it invests in negotiation.

- Prioritize stabilization and repairing local institutions. Where it pursues diplomatic solutions to conflict, the US government can help secure gains by investing in interventions that produce stability. The DRC shows how daunting the challenge of stabilization can be, with more than 2 million Congolese having faced displacement from the M23-driven conflict between January and June 2024 alone. Effective stabilization efforts require prioritizing humanitarian responses to meet the basic needs of families and communities experiencing displacement, return, and other traumas. It also must include supporting the reestablishment of local civil society and state institutions that can help deliver services, manage public goods, and resolve disputes.

The role of other actors: The private sector should foster multisector investments in peace and security

The long-term ability of private sector companies to operate and recoup investments in conflict-affected communities depends on durable peace and security. Direct investments in peace dividends (i.e., socioeconomic returns to peace) can help reinforce reductions in conflict. US and other private sector companies are optimally positioned to strengthen their local business environments by making social and economic investments that help communities and regions benefit from periods of relative calm while strengthening overall socioeconomic well-being. This can include making investments in local infrastructure, public goods, and service delivery capacities. Private sector actors, especially within the extractives sector, can also build on frameworks like the Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights and commit to business and human rights practices that reinforce good governance and security.

Committing to and growing who leads democracy assistance

During its first ten months in office, the Trump administration has removed long-standing infrastructure and funding for delivering democracy assistance globally, including in Africa. The near- and long-term interests of African societies and key US stakeholders, however, are bolstered by the advancement of democratic, accountable, and stable governance on the continent. Not only is a robust democracy assistance strategy in Africa in line with long-standing US values that underpin America’s reputation and image on the continent, but it is also instrumental to stated objectives of the current administration, such as expanding fair access to strong foreign markets and securing priority peace agreements.

Regardless of its ultimate policy, the US government is, at least for the time being, stepping back from traditional aspects of DRG programming. In this context, other institutional actors can do more. Private philanthropy and the private sector cannot replace US government democracy assistance, but they can make targeted, evidence-based, and cost-effective investments that protect important areas of intervention, such as emergency assistance for human rights defenders, institutional support for EMBs, and pro-peace investments in conflict-affected communities. These and other types of investments are affordable, and when well executed, they can positively influence the trajectories of individual democratic actors, institutions, and partner countries.

Private foundations are especially well positioned to pursue DRG investments while prioritizing direct support to African-based institutions. This can include forging mutual relationships among democratic actors grappling with common 21st-century democratic challenges in Africa, the United States, and beyond, to seed the sector with stronger horizontal ties and novel partnership approaches and new strategies for the future.

about the authors

Mason Ingram is vice president for governance at Pact, a nongovernmental organization that carries out development work around in the world in partnership with private sector organizations government agencies, including with USAID until the agency’s closure in 2025. Pact continues to receive funding from the US Department of State. Ingram has more than 15 years of experience designing, advising, and managing international development programs, with a focus on civil society and governance programming.

Alysson Oakley is vice president for learning, evaluation, and impact at Pact. Oakley also teaches courses on program design and evaluation of democracy assistance and conflict resolution interventions at Georgetown University. Oakley holds a PhD from Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies, and a bachelor of arts degree from Brown University.

Jack Higgins is a research assistant and MA candidate at Georgetown University’s College of Arts and Sciences.

The authors are grateful for consultations provided by experts on democratic governance in Africa, including Dr. Babra Ontibile Bhebe (executive director, Election Resource Centre), Bafana Khumalo (co-executive director, Sonke Gender Justice), Omolara Balogun (head, policy influencing and advocacy, West African Civil Society Centre), Jean-Michel Dufils (retired senior governance research expert and program manager), and Jon Temin (visiting fellow, SNF Agora Institute).

Related content

explore the program

The Freedom and Prosperity Center aims to increase the prosperity of the poor and marginalized in developing countries and to explore the nature of the relationship between freedom and prosperity in both developing and developed nations.

Image: September 23, 2025, Accra, Greater Accra, Ghana: Angry New Patriotic Party (NPP) demonstrators filled the streets of Accra demanding an end to state sponsored police harassment of party leaders and members, 23rd Septemer 2025 (Credit Image: © Frank Kporfor/ZUMA Press Wire)