Recommendations: Cooperation on maritime cybersecurity

Table of contents

A collaborative path forward for cybersecurity in the MTS

When plotting a course on the open ocean, conditions rarely allow a navigator to chart a straight line home. Hazards below the surface of every ocean and the unpredictability of weather systems require a crew to consistently reassess the vessel’s position and adjust maneuvering to reach its destination safely. Both the captain and the crew are expected to navigate using all means available, a lens that should apply to approaching recommendations to reduce cybersecurity risks for the MTS as a whole: actors within the MTS must be capable of tapping into every available resource.

The approach to maritime cybersecurity must ultimately be holistic; even if every component of the MTS was cyber secure, the interconnection of the subsystems might not result in a secure MTS. Taking the steps necessary to build a secure maritime domain will require a better understanding of the cybersecurity-threat landscape, coupled with a segmented view of MTS infrastructure. This will allow developers, policy makers, owners, and regulators to match the best policy levers with particular maritime systems, and achieve better cybersecurity outcomes across the entire MTS.

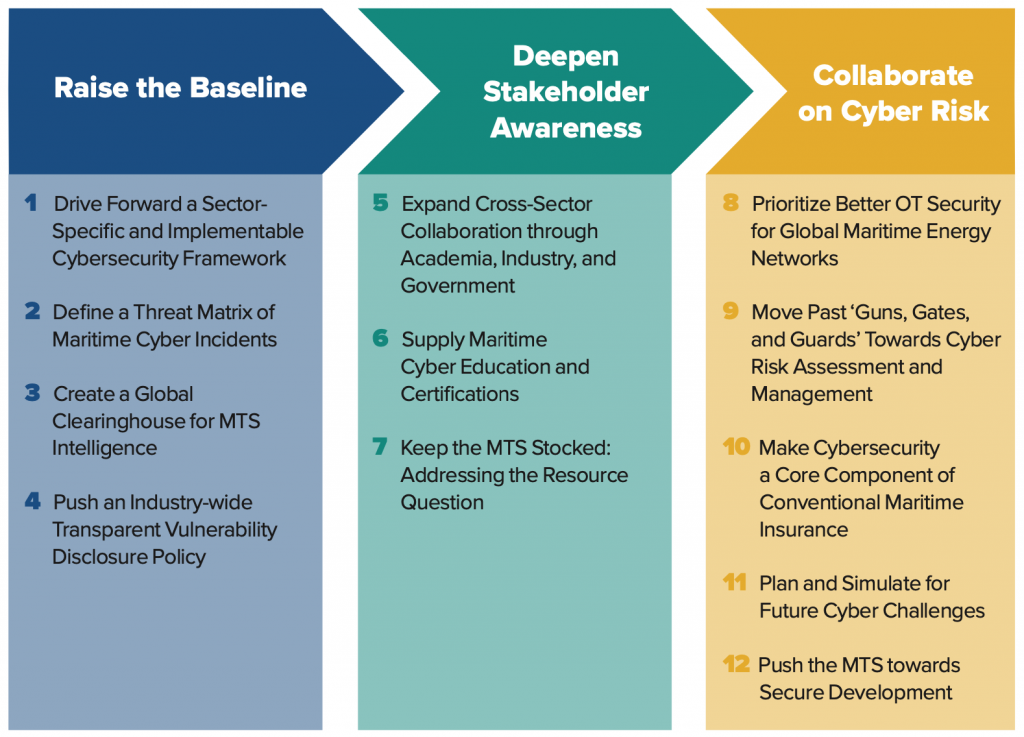

This report puts forward twelve recommendations—split into three overarching themes—to help better secure all subsystems of the MTS from evolving cyber threats. First, stakeholders operating within the MTS must raise the baseline for cybersecurity across the maritime industry and shipping communities. Knowing is half the battle, and stakeholders must develop a sector-specific cyber risk framework, a global intelligence clearinghouse, and a common cyber-incident threat matrix, while pushing for an active, industry-wide vulnerability disclosure policy.

Second, MTS stakeholders must deepen their understanding of maritime cybersecurity and associated risks by building cross-sector linkages, especially through new professional and international exchanges between academia, industry, and government. Stakeholders must design MTS cyber-specific educational certifications to support these new workforce initiatives, with the goal of upskilling the industry and attracting talent into a cyber-aware MTS. Developers and the maritime industry must collaborate on eradicating systemic software vulnerabilities from MTS software. Lawmakers and regulators must complement these efforts by ensuring that MTS receive adequate resources to improve cybersecurity.

Third, executives and high-level stakeholders in the public and private sectors globally must prioritize cybersecurity as part of their broader risk management efforts, leveraging increased security measures and appropriate risk mitigations to help support long-term improvements in cybersecurity. MTS stakeholders should assess risk by relating their cybersecurity maturity to those of other sectors, like energy, better integrating cybersecurity with traditional maritime insurance coverage, and finally, improving cybersecurity proactively through multistakeholder simulations.

The bulk of these identified actions build on or integrate existing programs, such as the US Department of Energy-backed Cyber Testing for Resilient Industrial Control Systems (CyTRICS) program,1“Cyber Testing for Resilient Industrial Control Systems (CyTRICS),” Idaho National Laboratory, August 9, 2021, https://inl.gov/cytrics/. run across four national labs and the Department of Transportation (DOT) Maritime Administration (MARAD) 2021 Port Infrastructure Development Program (PIDP).2“About Port Infrastructure Development Grants,” MARAD, accessed August 16, 2021, https://www.maritime.dot.gov/PIDPgrants. These programs are embedded in broader lines of policy effort and come with well-established relationships—both virtues over starting from scratch.

The maturity and effectiveness of contemporary approaches to cybersecurity in the MTS fail to reflect the vital role maritime transportation plays in supporting global commerce, diverse energy systems, and national security. Cyber threats will only continue to metastasize, accelerating both in quantity and consequence. Navigating through such turbulent waters requires an all-hands-on-deck approach—both in the United States and beyond—to improve the collective cybersecurity of the MTS.

Recommendations

Raise the baseline

Given the low baseline for cybersecurity in the MTS, the recommendations in this report focus on elevating the standard of cybersecurity by identifying four key problems that underpin this reality and require attention: a more specific set of cybersecurity guidelines, a clear threat matrix for maritime incidents, more streamlined intelligence sharing, and a codified vulnerability disclosure program. The recommendations in this section, numbered sequentially, seek to address these problems utilizing the points of leverage in the MTS identified in the previous life-cycle sections.

The first problem is how organizations approach security and guidelines for best practices. The IMO, the primary international maritime body, provided cybersecurity guidelines as recently as 2017, which rely heavily on the NIST Cybersecurity Framework’s five functions to provide high-level direction to MTS stakeholders. Despite the IMO’s guidelines, varied cybersecurity frameworks are developed and promulgated by both stakeholder organizations and multilateral bodies, such as BIMCO, the American Bureau of Shipping (ABS), and ENISA. Each framework changes and adds important elements, yet these modifications unintentionally create a tapestry of frameworks that clash at the operator level. For a sector that is already so complex in nature with a changing attack surface based on the type, function, and age of a ship or facility, cyber risk frameworks should not create added confusion.

The second problem is the need for a collective taxonomy of maritime cyber incidents and how those incidents should be logged and reported, as well as defining a minimum criterion for cybersecurity incidents to be reported. Cyber incidents will manifest differently across various sectors of the MTS. Present lack of reporting continues to erode the situational awareness that is essential for law enforcement and incident responders within the USCG to execute their mandate of prevention and response within US territorial waters and other deployment areas. The propensity for misreporting or underreporting incidents has the potential to result in the widespread compromise of critical MTS systems, which could cascade into the loss and damage of physical infrastructure, goods, and human life. The USCG should be able to accurately assess incoming ships and the ongoing cyber risk landscape of an operational area—but it will depend on an accurate incident log to do so.

The third problem is the need for more streamlined intelligence sharing within the MTS. According to the NMCP, there are more than twenty US federal organizations that have a role in the MTS. Additionally, numerous private, nongovernmental, and international organizations inundate federal organizations with an unsustainable number of intelligence requests; these varied actors are not equally able to dedicate resources to remediation efforts. The ability to quickly share intelligence with pertinent organizations is necessary but currently missing in the MTS.

The final issue is vulnerability disclosures. Vulnerabilities are inevitable; while vendors do not intentionally place vulnerabilities within their products, their continued presence presents a credible risk to the MTS and its critical systems. However, the low prioritization of cybersecurity within the MTS has led to a lax approach to addressing vulnerabilities or known public exploits. Vulnerability disclosure must be prioritized, as the ability to quickly address known flaws is a critical step to making any ecosystem more secure.

1. Drive a sector-specific cybersecurity framework with low barriers to implementation

The US government must continue and expand its role as a driver for safety guidelines within the MTS. Led by NIST, new cybersecurity framework profiles, based on the existing NIST Cybersecurity Framework, should focus on developing subsector specific guidelines and best practices for key players within the MTS that can be supported by international entities like BIMCO, ICS, and the IMO, as well as be easily adopted by industry actors.

- Building on the existing partnership between NIST and the MITRE Corporation, NIST, in partnership with key private-sector stakeholders, should develop industry-focused cybersecurity framework profiles tailored to address the risks and needs of specific subsystems of the MTS, prioritizing key commercial and energy terminals, major shipping liners, and port systems.

- Led by the USCG and State Department, these profiles should be promoted to and advocated for with international partners like the EU’s ENISA, as well as key international organizations such as BIMCO, ICS, and IMO. Specifically, the United States should use the inclusion of the NIST framework in IMO 2021 to push for international uniformity along a similar framework.

2. Define a threat matrix of maritime cyber incidents

As the established incident responder within the MTS, the USCG should design a threat matrix of MTS-specific cyber incidents. This matrix should be developed in partnership with the MTS, information sharing and analysis centers (ISACs), and key insurance entities, and be accessible and usable by regulatory bodies, incident responders, and insurers to identify, assess, and log cyber vulnerability in individual vessels and facilities across the MTS.

- Captains of US ports should establish cross-sector working groups in their individual operational regions to develop a unified threat matrix and taxonomy of incidents, and use this information to develop a new form, such as Form 2692 (Report of Marine Casualty, or OCS-related Casualty), on which operators can immediately map newly detected cybersecurity risks, vulnerabilities, and incidents to the threat matrix. Specifically, this process needs to involve key players in the insurance industry, as their frequent inspections provide them with the most extensive data and analytical capacity on risks facing the MTS.

- The USCG, led by the Commandant’s Office and supported by DHS and the Office of the National Cyber Director, should leverage its position within the international maritime community to push this new threat matrix and taxonomy of maritime cyber incidents to the international maritime community through the IMO, specifically targeting critical trade regions and waterways, such as the Panama Canal Authority or Suez Canal Authority, that would benefit the most from such an incident matrix when it comes to systemic risk reduction.

3. Create a global clearinghouse for MTS intelligence

To facilitate information sharing and prevent intelligence blockages across the global MTS, the USCG must establish a clearinghouse that can actively declassify MTS-relevant cyber-threat intelligence and provide global alerts to requisite stakeholders across the private sector and internationally.

- With resources and operational support from the intelligence community, DHS, in collaboration with the USCG, should promote the bilateral declassification and release of MTS cyber-threat intelligence and vulnerabilities as alerts, modeled after those of DHS CISA‘s rumor-control online resources for 2020 election security.3“Election Security Rumor vs. Reality,” Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency website, accessed August 12, 2021, https://www.cisa.gov/rumorcontrol.

- Using its captains of the port, and in conjuction with DOT, DOE, and DHS,4The captain of the port is the Coast Guard officer who gives immediate direction to Coast Guard law enforcement activities within his or her assigned area. For more information see 33 CFR § 6.01-3 [2013], made available electronically by the Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School, https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/33/6.01-3. the USCG should establish dialogue sessions focusing on clear communication channels, deconflicting roles, and streamlining collection functions across nongovernmental organizations (ISACs and ISAOs) and private companies engaged in MTS cyber-threat intelligence collection.

- Internationally, the State Department, the USCG, and DHS should separately look to engage with US allies, neighbors, and major trading partners, with the intent of creating deeper relations on information collection and sharing within the MTS. This should be explored with key maritime strategic partners such as Australia, the United Kingdom, Japan, Singapore, and the Netherlands.

4. Push an industry-wide, transparent vulnerability disclosure policy

The MTS, supported by the US government, should push a policy of transparency and openness around vulnerability disclosures. The business stakeholders and regulatory authorities—such as ship liners and class societies within the MTS—should work together and coordinate in encouraging software providers to follow a ninety-day disclosure policy or another mutually agreed-upon window.

- Led by business stakeholders and regulatory bodies, this policy will affect all vendors looking to provide systems to the MTS, whether for logistics, navigation, communication, or OT processes such as the transport of oil and natural gases. To minimize potential risk, vendors should be expected to provide alternative solutions for patching when other conditions prevent normal updates.

- Internationally, US representatives to the IMO should propose the creation of an IMO-housed, industry-led, disclosure body that can both independently identify, and be externally notified of, vulnerabilities to MTS-specific software.

Deepen stakeholder awareness

The next set of recommendations focus on the need to deepen understanding of maritime cybersecurity and its associated risks, and bring attention to the requisite best practices and workforce development for mitigating these risks across the MTS. Despite the trend of increasing cyberattacks targeting the maritime community, the MTS still lags when it comes to education and training related to cybersecurity. To promote a deeper understanding of cybersecurity in the MTS, the recommendations in this section strive to address three key problems: the need for more cross-sector collaboration and knowledge exchange, the lack of maritime cyber education and training programs in the MTS, and the need for additional funding to secure the MTS.

Part of the problem in the MTS has been a lack of understanding of stakeholder perspectives, with vessel operators unaware of vendor challenges, vendors unaware of the mentality of vessel operators, and regulators often prescribing unachievable targets due to lack of visibility into the industry. For an interconnected industry like the MTS, it is challenging to holistically secure the ecosystem if stakeholders do not understand the needs and perspectives of other, differentiated actors. Existing programs such as the USCG’s Marine Industry Training Program, which offers its forces “internships with maritime industry organizations and other regulatory agencies” for up to a year, are a step in the right direction. Yet, the MTS needs a more robust program, with the goal of instilling a culture of effective risk awareness, assessment, and management by encouraging exchanges between government, business, and academia to learn from one another’s cybersecurity experiences.

The second key problem is the shortfall in training and education around cyber risk in the MTS. Many of the vulnerabilities in the MTS exist because of the lack of knowledge of basic cyber hygiene. Beyond the insufficient general cybersecurity knowledge across the MTS, there also is a insufficient, albeit growing, maritime cybersecurity knowledge in the incident-response community. There is a pressing need to create a cybersecurity-capable workforce, ensuring cyber literacy among the next generation of mariners and operators.

Finally, more funding within the MTS is needed to support an increased focus on cybersecurity risk mitigation—especially within the USCG given their lead role in protecting US maritime assets. As the cyber-threat landscape continues to expand and more incidents warrant governmental intervention, additional funding, personnel, and training will be required. The NMCP outlines a major push for a maritime cybersecurity workforce, which echoes the objectives outlined by the USCG’s internal strategy documents to ensure that it develops a capacity to deal with MTS cyber issues. However, should the MTS threat landscape continue to grow in proportions and comparative scale, the system will quickly find itself understaffed, overburdened, and exhausted by incidents. While the multistakeholder nature of the MTS allows for greater involvement of private and nongovernmental actors in incident response, this may not be sufficient to adequately address significant cyber incidents.

5. Expand cross-sector collaboration through academia, industry, and government

Key US government organizations involved in the MTS—specifically, DOT, DOE, DHS, and USCG—should build upon such initiatives as USCG’s Marine Industry Training Program and Idaho National Laboratory’s OT Defender fellowship by bringing over key elements, including the exchange processes and the grant structure, from the United Kingdom’s comparable Knowledge Transfer Partnership program. This action can serve to not only increase the impact and scope of personnel transfers through the expansion of these programs, but also to lay out a road map for a more collaborative grant-making process that can help facilitate the scaling of these programs. Once established, these US government organizations, in partnership with the private sector, should work to expand OT Defender and the Marine Industry Training Program to include key partner states such as Australia, the United Kingdom, Japan, Singapore, and the Netherlands.

6. Supply maritime cyber education and certifications

In coordination with cybersecurity training and academic institutions, the USCG and DOT, supported by DHS and DOE, should commission curricula and industry-recognized certifications for MTS-specific OT and IT systems.

- This task force must prioritize developing educational modules, recognized by the IMO and International Class Societies and designed in consultation with system developers, which can allow existing members of either the MTS or the cybersecurity industry to upskill and move laterally between the two industries.

- Led by the USCG and MARAD, this task force must share this basic MTS cybersecurity-education road map with maritime and merchant marine academies within the United States and among strategic partners, outlining a basic course structure that academies can plausibly incorporate into their existing curricula.

- LThe State Department should propose a minimum requirement of cybersecurity training for crew interacting with OT/IT and IoT systems as an amendment to the IMO’s International Convention on Standards of Training, Certification, and Watchkeeping for Seafarers (STCW)

7. Keep the MTS stocked: Addressing the resource question

The White House must commit to identifying new funding for DHS that can be directed to the USCG’s increased involvement in protecting and responding to cybersecurity incidents specific to the MTS.

- Currently, the USCG earmarks approximately 10 percent, or $32.68 million, of its annual budget to cybersecurity. A 20-percent funding increase toward the USCG’s activities—specifically tagged for cyber-enabling operations, cyber operations and training, maritime-sector cybersecurity engagement, and cyber protection and defenses—should be considered. This increase should be coupled with top-line relief for the USCG’s whole budget, so that specific funding increases can actually be spent where they are intended to be instead of being repurposed for other projects.

- The USCG should use funding earmarked for maritime-sector cybersecurity engagement to expand its programs focused on working with private sector and weak state partners, to help support and facilitate a larger ecosystem shift toward more sustainable cybersecurity practices, and execute the various other activities outlined here as appropriate.

- Taking a page from the proposed National Cyber Reservist Force, the USCG and DHS should support the creation of a network of former cybersecurity and MTS specialists that can find employment opportunities within MTS stakeholders’ firms, especially those lacking strong cybersecurity, to help raise the baseline for the ecosystem.

Collaborate on cyber risk

The final set of recommendations encourages MTS stakeholders to leverage every opportunity to increase awareness of the cyber risks present within the sector and prioritize, both in funding and in action, the mitigation of threats. To help push for and incentivize more prioritization of cyber risk and cyber risk mitigation the MTS, the recommendations in this section strive to address five key problems: the urgent need to better secure critical energy network OT systems; the concentrated cyber risk that is present in ports; the current role of cyber insurance in the MTS; the lack of coordinated programs focusing on forecasting future cyber threats to the MTS; and, finally, an industry-wide push toward more fundamentally secure development practices.

First, there is an urgent need to better protect ICS and OT systems for energy networks within the MTS. ONG infrastructure is highly automated, and pipeline operators, terminal owners, and utilities alike rely on ICS products for monitoring and/or remote control. As ports modernize, all manner of vessels become more digitally dependent, and as offshore energy production (e.g., oil rigs, wind turbines) turns increasingly to automated controls, the systems that undergird critical functions and processes are highly desirable and increasingly accessible targets to cyber adversaries. Critical systems throughout the MTS are vulnerable to potential exploitation, but the stakes are especially high for MTS energy networks.

Second, the MTS must do more to protect ports. Ports, in many ways, are the most important part of the MTS, as they represent the point of synthesis where most players overlap. This synthesis results in a significant concentration of cyber risk. There is precedent for ports to quickly adapt security measures to emerging threats: after 9/11, there was a serious and effective push to increase physical security that remains necessary and in place to this day. The cybersecurity threats to port operations, especially those that play critical roles in global trade and the mobilization of military forces, suggest a similar adaptation is required in the way the port industry thinks about security.

Third, there is a lack of comprehensive and well-aligned insurance coverage for owners and operators in the MTS. Cyber insurance has emerged as a major product for insurance firms; a 2019 Lloyd’s report placed the potential total of premiums from cyber insurance near $25 billion by 2024.5“Lloyd’s Cyber Risk Strategy,” Lloyd’s, 2019, https://assets.lloyds.com/assets/pdf-lloyds-cyber-strategy-2019-final/1/pdf-lloyds-cyber-strategy-2019-final.pdf. Yet, simply having cyber insurance neither prevents nor protects an entity from cyberattacks.6Nicole Lindsey, “AIG Case Highlights Complexities of Covering Cyber-related Losses,” CPO Magazine, October 24, 2019, https://www.cpomagazine.com/cyber-security/aig-case-highlights-complexities-of-covering-cyber-related-losses/. In the aftermath of NotPetya, insurers informed victim organizations that they considered the attack to be an act of war, and, therefore, had negated their coverage.7Riley Griffin, Katherine Chiglinsky, and David Voreacos, “Was It an Act of War? That’s Merck Cyber Attack’s $1.3 Billion Insurance Question,” Insurance Journal, December 3, 2019, https://www.insurancejournal.com/news/national/2019/12/03/550039.htm. In recent years, the broader industry has seen cyber insurance and price setting for insurance premiums emerge as a new lever to encourage adoption of better cybersecurity practices. However, cyber insurance can also have the unintended consequences of discouraging organizations from investing in cybersecurity once they consider themselves covered. The focus on physical security and safety in existing maritime insurance plans further complicates cyber insurance for the maritime sector. Reworking these policies to include more holistic cybersecurity provisions, without discouraging investment, will be a tricky line to toe. For the MTS, this adjustment is vital, as it has developed a complex web of liability and responsibility between insurers, owners, operators, crew, and ship masters.

Next, the v should adopt a forward-looking approach to address and respond to emerging cyber threats. The MTS has long been structured to work for a just-in-time supply model, where production and therefore supply revolves around customers’ stated needs, rather than a broader and anticipatory just-in-case model that would protect the system.8Harry Dempsey, “Suez Blockage Will Accelerate Global Supply Chain Shift, Says Maersk Chief,” Financial Times, March 29, 2021, https://www.ft.com/content/e9452046-e88e-459a-9c54-341c85f3cb0d. The current mindset is not geared to cybersecurity, as the cyber threat landscape evolves on an almost daily basis. While MTS stakeholders are beginning to prioritize cyber risk in the present, they must keep a keen eye on the threats and vulnerabilities that may lie beyond the horizon.

The final key problem is the lack of knowledge and transparency around the cybersecurity of core maritime systems. As the global stakeholders within the MTS continue their efforts to increase automation, improve efficiency, lower costs, and adjust to an increasingly digital world, they will be increasingly reliant on software to monitor, compute, and execute critical tasks aboard a vessel. However, the security of these systems—and the maturity of the acquisition program that purchases these systems—does not match their criticality. System vendors exist in an ecosystem apart from the MTS and prioritize time to market, profit, and efficiency over security. As long as these attributes are deemed necessary for market competitiveness and valued over cybersecurity, the MTS will remain at a disadvantage before the fight begins.

8. Prioritize better OT security for global maritime energy networks

DOE CESER and FERC,9Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (website home page), accessed May 14, 2021, https://www.ferc.gov. in close partnership with key private-sector coordination groups such as the ONG-ISAC and the Electricity ISAC (E-ISAC), should use the specter of mandatory NERC CIP standards—potentially enforceable by audits and fines for noncompliance—to drive more effective self-regulation on the security of port, shipping, and cruise systems to better the cybersecurity posture of energy and related MTS systems. Standards should be implemented in close partnership with key private-sector actors to prevent overly restrictive standards; enabling these actors to make the right decisions for the right reasons without unnecessary cost is key.

- Starting with an ONG-ISAC led review of the most relevant policies surrounding system cybersecurity within DOE, DHS, and DOD and in consultation with the national labs, industry should work to define standards for rapidly testing and deploying patches, updates, and new hardware to mitigate cybersecurity risk in mixed IT/OT deployments for semipermanent and mobile assets, especially those operating in high-traffic areas.

- CESER and CISA should work with the largest actors in the private sector to mandate, or at least promote, governance-structure updates for the MTS, including the creation of a senior security and resilience position (vice president or higher) where such does not currently exist within private-sector entities. This type of position should have purview over IT and OT systems, as well as cyber and physical security, and report regularly to the chief executive officer and board of directors or equivalent.

9. Move past “guns, gates, and guards” toward cyber risk assessment and management

Through current DHS and USCG efforts led by the captains of the port function, additional funding should be identified and either allocated to FEMA’s Port Security Grant Program (PSGP) and DOT MARAD’s Port Infrastructure Development Program (PIDP) or earmarked to develop a dedicated port cybersecurity-improvement grant managed by MARAD. This funding should be used to expand this work, with a specific focus on dedicated grants and funding for cybersecurity assessments and developments.

- Additionally, DHS should adapt the model deployed after 9/11 to provide more stringent requirements for cybersecurity-improvement grants, aiding the state public administrators who facilitate these federal grants. DHS should also encourage ports to take the initiative to improve their own cybersecurity, as the Port of Los Angeles has done in collaboration with IBM.10“IBM Works with Port of Los Angeles to Help Secure Maritime Supply Chain,” Press Release, IBM (website), December 7, 2020, https://newsroom.ibm.com/2020-12-07-IBM-Works-With-Port-of-Los-Angeles-to-Help-Secure-Maritime-Supply-Chain.. However, in this process, DHS and the USCG must be willing to be strict supervisors, and invite private-sector risk assessors to critically evaluate improvements, thereby ensuring improvements comply with a broader security vision for the MTS.

- Internationally, port operators should be encouraged by the USCG to expand their existing, and create new, international sister-port partnerships that focus on operational cybersecurity best practices. International companies should be encouraged to weigh the security advantages of collaboration on maritime cybersecurity by engaging with two sister ports.

10. Make cybersecurity a core component of conventional maritime insurance

Following the example of the automotive industry in recent years, insurers should push maritime clients to achieve and maintain stronger cybersecurity postures—in line with the guidelines put forward by NIST and the IMO—in exchange for premiums that reflect a commensurate level of risk reduction. Premium pricing should be benchmarked to recognize and reward those who make incremental investments toward stronger and more holistic cybersecurity practices.

- DOT MARAD’s Office of Safety should implement regulations requiring ships to possess insurance that requires mature levels of cybersecurity coverage. This can be enforced by the USCG and DHS Customs and Border Protection.

- Insurance companies dealing with cyber and maritime insurance should be encouraged to partner with research institutions like think tanks and the national labs to conduct long-term studies in this area to better address these emerging issues of potential financial risk.

11. Plan and simulate for future cyber challenges

The US government should utilize existing intelligence and military alliances, such as the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (involving the United States, Japan, India, and Australia), NATO, and the Five Eyes intelligence alliance, to host international, live maritime cybersecurity-focused exercises that heavily feature private-sector involvement. While exercises already exist that focus on known vulnerabilities and perceivable threats, these efforts should be built upon and expanded to include technology vendors, ship liners, and port operators. These organizations would benefit from annual exercises forecasting risks to the MTS, and, in turn, their increased preparedness will help increase the resiliency of the broader ecosystem. There are two distinct models that should be developed.

- Led by the USCG, key stakeholders within the global MTS should come together to participate in a series of tabletop exercises focused on identification, mitigation, and response to emerging cyber threats to the MTS. The program should be built upon the USCG’s Project Evergreen Strategic Foresight Initiative and include both elements and stakeholders from the E-ISAC’s annual GridEx exercise.

- Building upon the Army Cyber Institute’s Jack Voltaic program community and NATO Locked Shields, the NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence (CCDCOE) should develop an international, integrated, live exercise that allows stakeholders in the MTS to practice incident response and collaboration in real time. The program should be expanded to explicitly focus on incident detection and response for ships, ports, and cargo transport operations while at sea and at rest under live conditions with allies.

12. Push the MTS toward secure development

Led by the International Chamber of Shipping, operators within the MTS should look to establish a solution-oriented dialogue with key global maritime manufacturers and software vendors to design a more secure software-development life-cycle maintenance process for the industry. A push by MTS stakeholders can be subsequently coupled with government efforts, led by DHS CISA, that are being considered in the wake of the Sunburst campaign. Internally, MTS businesses should be encouraged to improve their acquisition processes to require penetration testing and cyber-vulnerability assessments of technical products.

- The MTS must work directly with entities within the US government to develop and leverage common risk-assessment processes to rigorously and proactively assess MTS system providers. Efforts must be undertaken to shift from security that is operational by intent to products that are secure by design. The MTS is continually evolving into a more connected ecosystem, yet, until that happens, vessel- and port-based products must be secure. Secure design must be the goal, and the FASC is the body best positioned to advance this effort. Internationally, the United States—led by the State Department, DOT, and key private-sector stakeholders—can work to build and petition the inclusion of these secure-by-design recommendations into a new set of cybersecurity guidelines released by the IMO to its members, like IMO 2021.

- In an effort led by the US Department of Commerce’s (DOC) NTIA)” content=”An Executive Branch agency that is principally responsible for advising the President on telecommunications and information policy issues.”],11National Telecommunications and Information Administration, NTIA home page, accessed May 4, 2021, https://www.ntia.gov/. new products coming into the MTS should be required to provide a “software bill of materials (SBOM), a formal record containing the details and supply-chain relationships of the various components used in building software.”12Exec. Order No. 14028, 86 Fed. Reg. 26633 (May 12, 2021), https://fas.org/irp/offdocs/eo/eo-14028.pdf. This information provides users insight into their true exposure to software supply-chain vulnerabilities and attacks, and allows operators to respond to new threats and attacks more rapidly.

- The DOE, in partnership with the DOE national labs and key stakeholders in industry, should push key maritime system manufacturers to buy into the DOE’s Cyber Testing for Resilient Industrial Control System (CyTRICS) program to focus on accessing and protecting core OT systems for the maritime domain.13Office of Cybersecurity, Energy Security, and Emergency Response, “DOE CESER Partners with Schneider Electric to Strengthen Energy Sector Cybersecurity and Supply Chain Resilience,” CESER News Release, US Department of Energy, September 23, 2020, https://www.energy.gov/ceser/articles/doe-ceser-partners-schneider-electric-strengthen-energy-sector-cybersecurity-and. The program will help support cyber vulnerability testing for key systems and provide a process for sharing “findings with manufacturers to develop mitigations and alert industry stakeholders using impacted components so they can address flagged issues in their deployed systems.”14Office of Cybersecurity, “DOE CESER Partners with Schneider Electric.”

Conclusion

The MTS is sailing into turbulent waters and needs all-hands-on-deck preparedness to guide it through cyber threats and into safe harbor. The United States has recognized the threats adversaries pose to the MTS, but it cannot address the challenge alone. A diverse set of stakeholders across the MTS must work together to mitigate maritime cyber risk.

This report works to provide an entry point for all parties within the MTS by building a cohesive picture of key life cycles within the MTS, as well as highlighting significant cybersecurity risks. Misunderstanding or underestimating the maritime cybersecurity risk landscape has real consequences for the integrity of global trade and energy markets. Everyone depends on moving resources across oceans; everyone is a stakeholder.

The MTS is changing, and with that change comes a tough set of challenges. This report’s recommendations can act as an engagement plan to complement existing maritime industry and policy efforts. These efforts must open dialogue among a diverse set of industry and allied stakeholders to protect national- and economic-security interests.

Port and ship operators must move forward in the interconnected and data-rich world of the twenty-first century to better serve clients and maintain operational excellence. Yet doing so brings increased reliance on OT and IT systems that expand attack surfaces within the maritime environment, and injects new vulnerabilities for which remedies remain insufficient.

By raising the baseline for cybersecurity, deepening stakeholder awareness, and folding cybersecurity into its understanding of risk, MTS stakeholders can improve their security postures and bolster safeguards to the MTS’s core role in global trade and energy.

Collaboration is key in the MTS—across the private and public sectors, within academia, and among governments the world over—to understand complex problems, better prepare for the future, and implement solutions to these pressing challenges.

Acknowledgments

This project would not have been possible without the support of Idaho National Laboratory and the Department of Energy. Specifically, the authors would like to thank Virginia Wright, Geri Elizondo, Andrew Bochman, Tim Conway, Frederick Ferrer, Rob Pate, Sean Plankey, Nick Anderson, and Puesh Kumar.

Thank you to the staff and researchers who supported this project from its inception, including Trey Herr, Madison Lockett, and Emma Schroeder. Thank you to Nancy Messieh and Andrea Ratiu for their support in managing the digital design and web interactivity of this report, and to Donald Partyka for designing the report’s graphics. For their peer review, the authors thank Alex Soukhanov, Suzanne Lemieux, and Marco Ayala.

Thank you to the participants of the various workshops held over the past year for feedback on this effort and to the numerous individuals who lent their insights and expertise with the authors during that time.

Disclaimer

This material is based upon work supported by the U.S. Department of Energy through the Idaho National Laboratory, Contract Number 241758. This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, expressed or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof.

Author biographies

William Loomis is an assistant director with the Atlantic Council’s Cyber Statecraft Initiative within the Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security. In this role, he manages a wide range of projects at the nexus of geopolitics and national security with cyberspace, with a focus on software supply chain security and maritime cybersecurity. Prior to joining the Atlantic Council, he worked on market research and strategy at an emerging technology start-up in Madrid, Spain. He is also a certified Bourbon Steward.

Virpratap Vikram Singh is a consultant with the Atlantic Council’s Cyber Statecraft Initiative within the Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security. He is the Cyber and Digital Fellow for the Saving Cyberspace Project at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs, supporting research and programming pertaining to cyber conflict and cybersecurity policy. Over the last two years, he has designed and authored multiple scenarios for the Initiative’s Cyber 9/12 Strategy Challenges in New York, Austin, and Washington D.C. Previously, he worked as the Digital Media and Content Manager for Gateway House, a foreign policy think tank in Mumbai. He holds a Master in International Affairs (International Security Policy) from Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs and a BA in Liberal Arts (Media Studies and International Relations) from the Symbiosis School for Liberal Arts.

Gary C. Kessler, PhD, CISSP, is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Cyber Statecraft Initiative. He is president of Gary Kessler Associates, a consulting, research, and training company located in Ormond Beach, Florida, and a principal consultant at Fathom5, a maritime digital services company headquartered in Austin, TX. He has been in the informationsecurity field for more than 40 years. Gary is the co-auhor of “Maritime Cybersecurity: A Guide for Leaders and Managers,” as well as more than 75 other papers, articles, books,andb ook chapters about information security, digital forensics, and technology. He has been a speaker at national and international conferences for nearly 30 years.

Xavier Bellekens is a non- resident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Cyber Statecraft Initiative within the Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security. He is the CEO of Lupovis Defence, and used to work as an Assistant Professor and Chancellor’s Fellow in the Institute for Signals, Sensors and Communications with the Department of Electronic and Electrical Engineering at the University of Strathclyde, Scotland. His experience spans from cyber-defence, deception, deterrence and attribution of cyber-threats in critical infrastructures to cyber-situational awareness and cyber psychology and cyber-diplomacy.

Explore the full report

These Recommendations are part of a larger body of content encompassing the entirety of Raising the colors: Signaling for cooperation on maritime cybersecurity— use the buttons below to explore this report online.

The Atlantic Council’s Cyber Statecraft Initiative, within the Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security, works at the nexus of geopolitics and cybersecurity to craft strategies to help shape the conduct of statecraft and to better inform and secure users of technology.