Introduction: Cooperation on maritime cybersecurity

Introduction

Oceans have long been the lifeblood of international trade and commerce. For more than five thousand years, humans have used rivers, lakes, and the seas to move goods from place to place quickly and efficiently.1“The History of the Maritime Industry,” North American Marine Environment Protection Association, August 8, 2018, https://namepa.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Lesson-3-The-History-of-the-Maritime-Industry.pdf. As civilizations continued to expand and better understand the strategic advantages of maritime trade, this usage accelerated. Initially logs bound together with rope, watercraft evolved into small, carved, wooden vessels. Before long, the first major trade routes began to surface—and the global maritime transportation network was well on its way.

Today, maritime transportation contributes to one-quarter of US GDP, or some $5.4 trillion.2Dan Ronan, “Ports, Shipping Industry Responsible for 26% of US GDP, Study Says,” Transport Topics, April 10, 2019, https://www.ttnews.com/articles/ports-shipping-industry-responsible-26-us-gdp-study-says. No global supply chain is independent of maritime transport, and most, in fact, are existentially dependent on it. Outside the United States, the sea and ports worldwide moved around 80 percent of global trade by volume and over 70 percent of global trade by value.3“Review of Maritime Transport 2018,” UNCTAD. Global maritime trade continues to gather momentum; in 2018, the industry expanded by 4 percent globally—the fastest growth in five years.4“Review of Maritime Transport 2018,” UNCTAD.

The maritime transportation sector also is crucial for the success of other critical infrastructure sectors —specifically, the security of global energy systems. In 2016, more than 61 percent of the world’s total petroleum and other liquid energy supply was moved through sea-based trade.5Business Wire press release, “Global Marine Fuel Market (2020 to 2025).” Maritime shipping as a form of transportation is essential for bulk transport of these raw materials due to the sheer volume of goods that must be moved and the competitive price point the MTS offers.6Business Wire press release, “Global Marine Fuel Market (2020 to 2025).” Maritime trade is essential for supplying fuel to the global economy.

A critical part of the United States’ national security is the ability to project power across the oceans; the shipping industry is a crucial cog of this wheel. Sealift—the ability for large-scale transportation of troops, supplies, and equipment by sea—is the basis of US military power projection, handling more than 90 percent of the US Department of Defense’s (DOD) wartime transportation requirements.7Sinclair Harris et al., “Sealift: The Foundation of US Military Power Projection,” Logistics Management Institute (LMI) blog, May 21, 2020, https://www.lmi.org/blog/sealift-foundation-us-military-power-projection. Sealift is the largest provider of strategic mobility, a driver of economic prosperity during wartime, and a key contributor to the US military’s global operating model. Sealift has manifested in variety of ways, including shipping essential supplies such as oil and natural gas (ONG) to the Middle East in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom,8“Maritime Industry Still Important Facet of National Security,” Federal Drive Time with Tom Temin (eponymous podcast with guest Brian Clark, a senior fellow), Federal News Network, March 31, 2020, https://federalnewsnetwork.com/workforce/2020/03/maritime-industry-still-important-facet-of-national-security/. or providing humanitarian assistance to the Philippines after brutal natural disasters, such as Typhoon Haiyan.9“Uptempo: The United States and Natural Disasters in the Pacific,” New America, accessed August 5, 2021, https://www.newamerica.org/resource-security/reports/uptempo-united-states-and-natural-disasters/part-ii-military-humanitarian-and-disaster-relief-response-capacity-in-the-indo-pacific-region/. The central role of sealift in enabling a diverse set of global operations—and the need to use maritime transportation to enable agile and strategic activity below the level of armed conflict, such as freedom of navigation operations, makes maritime security essential to US national security.

The Merchant Marine Act of 1920—better known as the Jones Act—further defines the relationship between the MTS and national security.10“Jones Act,” Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School website, https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/jones_act. Signed into law just after World War I, the Jones Act seeks to promote and maintain the US merchant fleet to ensure that the country will have sufficient merchant sealift capacity in the event of a conflict or an incident requiring the transport of large volumes of personnel and materiel. Among other provisions, it stipulates that any vessels transporting passengers or goods—even liquefied natural gas (LNG)—between US ports must be built, owned, flagged, and crewed by US citizens or permanent residents. A century since the Jones Act’s enactment, there are fewer than two hundred vessels that fulfill the statute’s criteria,11“Number and Size of the US Flag Merchant Fleet and Its Share of the World Fleet,” US Bureau of Transportation Statistics, https://www.bts.gov/content/number-and-size-us-flag-merchant-fleet-and-its-share-world-fleet. many of which rely on subsidies from the government to maintain that capacity. Despite being one of the largest producers of natural gas, the United States is restricted by the Jones Act from shipping its own LNG to domestic ports on noncompliant vessels.

More broadly, maritime trade also plays a key role on the global geopolitical stage for allies and potential adversaries. The United States is dependent on the ability to import goods from its allies via maritime transport: around 90 percent of US total imports arrive by sea. China, a near-peer rival of the United States, is acutely dependent on imports of oil and key resources such as iron to fuel its growing economy—goods that are almost exclusively transported through maritime trade routes.12Ishaan Tharoor, “What the Ever Given Saga Taught Us about the World,” Analysis, Washington Post, March 30, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2021/03/30/suez-canal-ever-given-lessons/. Maritime security is of vital interest to China, as the geography of the the Asia-Pacific region and, specifically, the strategically significant straits of Malacca and Singapore represent some of the most critical choke points and active trade routes in the the world13Lejla Villar and Mason Hamilton, “Maritime Choke Points Are Critical to Global Energy Security,” US Energy Information Administration, August 1, 2017, https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=32292.—and global maritime traffic has increasingly concentrated on these geostrategic choke points.

All of these factors have driven industry players to boost efficiency, automation, and remote management, in a word, more technology. The result however is widespread adoption of software and hardware without adequate corresponding management of the growing specter of cyber risk.

Complexity begets insecurity

Much like many other critical infrastructure industries, operational efficiency and profit drive maritime transportation. That drive has caused a shift toward an even more complex environment—and complexity begets insecurity. As the size of the global economy and its reliance on maritime activity have accelerated, the maritime transportation sector has had to scale up its operations. Over the last fifty years, the size and capacity of cargo ships have increased 1,500 percent.14Villar and Hamilton, “Maritime Choke Points.” In many ways, this dramatic scale-up has been essential for the industry. It has allowed for an exponential increase in sea trade and has driven prices down internationally. This rapid increase in size, however, has resulted in ships, and the MTS more broadly, becoming more complex.

The MTS is not monolithic. It’s a “system of systems” composed of ships and ports, but also the shipping lines, manufacturers, intermodal transport operators, cargo and passenger handlers, vessel traffic control, and maritime administrators. Each of these is itself a system of systems with complex internal and external dependencies. While all ports have similarities, they vary in their ownership and tenant models, cargo- and passenger-handling capabilities, mix of civilian and military vessels, jurisdictional authorities, and more. Similarly, all ships have some common functions, but are fundamentally different in areas such as operation, cargo and passenger capabilities, and crew requirements. Applying regulations to vessels is often complicated by the fact that one’s country of registration, ownership, and management might all be different, thus often requiring the coordination of several countries when adjudicating an incident.

Cybersecurity needs to be implemented and practiced by people engaged in all maritime activities—not just IT experts. The users of the MTS are a mixed lot: they work for a wide variety of organizations, play myriad roles, and have varied professional backgrounds and experiences. A given body of water might see any combination of commercial, law enforcement/public safety, military, cargo, passenger, recreational, maintenance, and other types of boats—not to mention offshore drilling or wind platforms, weather and navigation buoys, and sea-based communication platforms.

For years, the maritime sector developed and deployed unique software and hardware, inherently limiting their connectivity and risk exposure.15Trey Herr, Will Loomis, and Xavier Bellekens, “Trouble Underway: Seven Perspectives on Maritime Cybersecurity,” Atlantic Council blog, March 01, 2021, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/trouble-underway-seven-perspectives-on-maritime-cybersecurity/. However, the interconnected and data-rich world of the twenty-first century has provided ship and port owners and operators with an opportunity to integrate more ubiquitous IT systems with OT ones. These changes have led to increased automation, digitalization, levels of operational efficiency, and of course, better margins for owners and operators. Despite the MTS’s increasing deployment of OT and interconnected technology, from ships to rigs to ports, the sector has not proportionally increased its focus on cybersecurity.

Existing cybersecurity efforts in the MTS prove that it is tough to securely design, develop, and operate a fully connected environment—and even more so when these environments look different on a ship-to-ship and port-to-port basis. The MTS’s increased reliance on converging OT and IT systems has introduced new vulnerabilities and expanded the attack surface in the maritime environment—yet the focus and resources devoted to combatting these new threats still largely lags this development. In the integrated MTS, cybersecurity is only as good as the weakest link. It is critical that all links in the MTS logistical chain collaborate in establishing robust programs, properly training personnel, and maintaining the operational efficiency necessary for all parts to work as one.16Herr, Loomis, and Bellekens, “Trouble Underway.” However, this is easier said than done.

The consequences of this disconnect—the shortfall in cybersecurity investment compared to the increase in automation and digitization—have become increasingly clear in recent years. This often manifests itself similarly to other industries. Ransomware and phishing, two of the more common tactics and means of compromise globally, exist extensively throughout the MTS. In fact, all four of the world’s largest maritime shipping companies—A. P. Moller-Maersk (Maersk, as it is known, is part of the A. P. Moller Group), China Ocean Shipping Company (COSCO) Group, and Mediterranean Shipping Company (MSC)—have been hit by significant cyberattacks since 2017.17Catalin Cimpanu, “All Four of the World’s Largest Shipping Companies Have Now Been Hit by Cyberattacks,” ZDNet, September 28, 2020, https://www.zdnet.com/article/all-four-of-the-worlds-largest-shipping-companies-have-now-been-hit-by-cyber-attacks/. Maersk, whose business operation systems were ravaged when the NotPetya malware spread from an infected Ukrainian tax-preparation software called MeDoc, spent more than $300 million to return to full operations after ten days of repair and remediation.18Andy Greenberg, “The Untold Story of NotPetya, the Most Devastating Cyberattack in History,” Wired, August 22, 2018, https://www.wired.com/story/notpetya-cyberattack-ukraine-russia-code-crashed-the-world/. A reported 400-percent increase in maritime cyberattacks during 2020, along with a 900-percent increase in attacks targeting ships and port systems over the prior three years, point to a maritime industry in the crosshairs of malicious cyber actors. Despite this, the industry and its regulators have only slowly begun to move toward meaningful and systemic change.

Given the complexity and segmented ownership of the organizations comprising the MTS, as well as the range of threats, there is no single authority or cybersecurity model that easily applies to the entire industry. A more modular approach is needed to take a collective understanding of vulnerabilities and threats, and segment the MTS into individual systems that can support one another and/or leverage gains in other systems, and be addressed by policy makers. The approach ultimately must be holistic; even if every component of the MTS was cyber secure, the interconnection of the subsystems might not result in a secure whole. A better understanding of the cybersecurity threat landscape, coupled with a segmented view of MTS infrastructure, will be necessary to build a secure maritime domain. This approach will allow developers, policy makers, owners, and regulators to match the best policy levers with particular maritime systems, and achieve better management of cyber risk across the entire MTS.

Threats

The elements, pirates, and rival powers have challenged the maritime shipping industry for thousands of years. As the industry expands in size and integrates new technologies for added efficiency, the volume of potential threats,19“Maritime Industry Sees 400% Increase,” Security. and the consequences of potential disruption increase exponentially.

In addition to the implementation of new and insecure technology, in the last several years new problems and worsening effects have challenged the maritime industry in different ways. In early 2021, a Maersk vessel lost 260 containers overboard—about 2 percent of its cargo—when the ship lost propulsion for less than four minutes in heavy seas.20“Updated: Maersk Boxship Losses [sic] 260 Container [sic] Overboard during Blackout,” Maritime Executive, February 17, 2021, https://www.maritime-executive.com/article/blackout-on-maersk-boxship-causes-another-significant-container-loss. This was not an isolated incident; both MSC and NYK Shipmanagement (NYKSM) have each had significant and comparable incidents since late-2020.21Mike Schuler, “More Containers Lost in the Pacific as 41 Go Overboard from MSC Ship,” gCaptain website, February 2, 2021, https://gcaptain.com/msc-boxship-loses-containers-in-the-pacific/; and Kim Link-Wills, “Storm-beaten ONE Apus Berths in Japan,” American Shipper, a FreightWaves unit, December 8, 2020, https://www.freightwaves.com/news/storm-beaten-one-apus-berths-in-japan. Over the last decade, the World Shipping Council estimated that an average of 1,382 containers have been lost overboard annually.22World Shipping Council, “Containers Lost at Sea: 2020 Update,” undated PDF, https://www.worldshipping.org/Containers_Lost_at_Sea_-_2020_Update_FINAL_.pdf. While not all of these losses are linked to cyber incidents, they illustrate how much risk exists in the ecosystem, and how the increased scale and complexity of the MTS have given rise to new concerns.

The COVID-19 pandemic is evidence of the effects that a massive disruption can inflict on the MTS. The pandemic challenged the maritime industry with port closures, a new and shifting demand landscape, significant supply-chain disruptions, and operational questions around health and safety. As a result, for the first time in decades, global maritime trade actually dropped 4.1 percent in 2020.23“COVID-19 Cuts Global Maritime Trade, Transforms Industry,” UNCTAD, November 12, 2020, https://unctad.org/news/covid-19-cuts-global-maritime-trade-transforms-industry. No doubt, the pandemic also will have long-term effects on the industry that are hitherto impossible to quantify. COVID-19 forced states to think differently about their international relationships and trading patterns.24Marcus Baker, “The Pandemic Is a Top Maritime Industry Issue—But It’s Not the Only One,” Brink, a news platform of Marsh McLennan Advantage, October 12, 2020, https://www.brinknews.com/coronavirus-pandemic-becomes-a-top-maritime-industry-issue-but-its-not-the-only-one/. The economic and security consequences of such a large-scale disruption shocked many—and proved how unprepared the MTS is for such systemic challenges.

The most recent and probably most notable single-event example of an MTS-wide disruption occurred when Ever Given, one of the largest commercial container ships in the world, got stuck shortly after entering the Suez Canal in March 2021, blocking through traffic on one of the world’s busiest waterways. The vessel, at 1,300 feet (400 meters) and nearly 221,000 gross tons, was stuck for more than six days and took several days of work from one of the world’s best salvage teams, a fortuitous high tide, and a dash of luck to unwedge. Although the cause of the incident is believed to be a combination of heavy winds, the ship’s speed, and the vessel’s rudder size/alignment rather than a cyber attack,25Mia Jankowicz, “Here Are the Main Theories of How the Ever Given Got Stuck in the Suez Canal,” Business Insider, March 30, 2021, https://www.businessinsider.com/how-ever-given-got-stuck-in-suez-canal-main-theories-2021-3. the mishap caused global economic disruption. With 13 percent of global trade passing through it every year, the narrow Suez Canal is one of the most strategically important choke points in the world.26“SCZone Head: 13% of World Trade Passes through Suez Canal,” Hellenic Shipping News, June 24, 2019, https://www.hellenicshippingnews.com/sczone-head-13-of-world-trade-passes-through-suez-canal/. The resultant blockade of Suez Canal traffic held up $9.6 billion in goods.27Justin Harper, “Suez Blockage Is Holding Up $9.6bn of Goods a Day,” BBC News, March 26, 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/business-56533250. Once unstuck, the price to “refloat” the ship landed at $900 million, to be followed by a dispute over financial damages that ended in the seizure of Ever Given for nearly four months by Egyptian authorities.28Mostafa Salem, Mai Nishiyama, and Pamela Boykoff, “Egypt Impounds Ever Given Ship over $900 Million Suez Canal Compensation Bill,” CNN Business, April 14, 2021, https://www.cnn.com/2021/04/13/business/ever-given-seized-compensation-bill-intl/index.html.

The Ever Given incident illustrates the scale of disruption that a cyber incident could have on global shipping, especially in geostrategic choke points. It also exemplifies the complexity and interconnectedness of the global maritime system. Ever Given was owned by a company in Japan, operated by a container shipping firm based in Taiwan, managed by a German company, registered in Panama, and crewed by twenty-five Indian nationals.29Tharoor, “What the Ever Given Saga Taught Us,” Analysis. The complex, interconnected, and multinational nature of the MTS makes coordination challenging and finger pointing around incidents common—but also provides the industry with a unique opportunity to leverage systemic and global change if handled correctly.

There are precedents for high-consequence cyber events causing disruption on the MTS, including in the United States. In November 2020, the Port of Kennewick was hit by sophisticated ransomware attack that forced operators to rebuild the Washington state port’s digital files from offline backups.30Martyn Wingrove, “Cyber Attack Shuts Down US Port Servers,” Riviera news hub, Riveria Maritime Media, November 23, 2020, https://www.rivieramm.com/news-content-hub/news-content-hub/cyber-attack-shuts-down-us-port-servers-61955. This was not an isolated incident, but emblematic of a larger trend.31Nicole Sadek, “Shipping Companies Confront Cyber Crooks as Economies Reopen,” Bloomberg Government (news and analysis service), June 29, 2021, https://about.bgov.com/news/shipping-companies-confront-cyber-crooks-as-economies-reopen/.

The cyber-threat landscape in the MTS is similar to that of other critical infrastructure sectors. Global Positioning System (GPS) and Automatic Identification System (AIS) jamming and spoofing, attacks on less-than-secure OT and industrial control-system (ICS) devices, human targets, myriad shipboard information and communications technology (ICT) systems, are just some of the vectors that adversaries can and will use to attack the MTS. Ransomware, software supply-chain attacks, and social engineering are a few common tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTP) that have been used against the MTS. Potential targets and victims throughout the MTS include ships, ports, passenger and cargo shipping lines, shipbuilders and maritime manufacturers, and others. It is a complex and extraordinarily dynamic ecosystem that is difficult to defend. Cyberattacks represent an existential threat to the contemporary maritime industry, the smooth operation of which underpins modern society.

Attackers as diverse as the MTS: Pirates to pwners

The MTS’s vulnerability to cyberattacks and its significance to US national security and economic stability have drawn from the woodwork an array of adversaries intent upon wreaking harm on the ecosystem.

Just as the MTS is not monolithic, neither are those posing a threat to it. There is no single profile of a threat actor and motivation for attacking maritime cyber systems. Sun Tzu’s well-known saying about knowing thy enemy applies here: “If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles. If you know yourself but not the enemy, for every victory gained you will also suffer a defeat. If you know neither the enemy nor yourself, you will succumb in every battle.” Understanding where your risk is concentrated and who may look to exploit that risk are essential steps to securing an organization’s systems.

Attackers in cyberspace generally fall within the following categories based largely on intent.32Gary C. Kessler and Steven D. Shepard, “Maritime Cybersecurity: A Guide for Leaders and Managers” (self-pub., 2020), 49-50.

- Cybercriminals: Like criminals in the physical domain, cybercriminals are after financial or other tangible rewards; they are not ideologues, they want the cash. Cybercrime costs the global economy more than $1 trillion annually.33Jai Vijayan, “Global Cybercrime Losses Cross $1 Trillion Mark,” Dark Reading news site, December 9, 2020, https://www.darkreading.com/attacks-breaches/global-cybercrime-losses-cross-$1-trillion-mark/d/d-id/1339655. Cybercriminals in the MTS engage in cyberfraud and are behind most ransomware campaigns.

- Cyber activists/Hacktivists: Philosophy, politics, social movements, and other nonmonetary goals motivate this group of threat actors. Typical tactics of hacktivists include defacing websites, launching protests on social media, and conducting acts of cyber vandalism; while often criminal in nature, the intent is rarely financial.

- Terrorists: The use of cybersecurity capabilities by a traditional terrorist actor could mirror an act of terrorism in real space—a violent criminal action, meant to intimidate or cause fear—and be motivated by political aims. This fear could directly, or indirectly, yield disruption with significant economics effects. Terrorrist groups also often engage in cyberattacks with financial motivations to fund other operations and help support recruitment.

- State-sponsored entity: State-sponsored entities: These actors often report to or receive support from nations or states. Acts of financial, industrial, political, and diplomatic espionage in cyberspace are the most common objectives for this type of entity. Intellectual property (IP) theft, in particular, costs the global economy more than $2 trillion annually by some estimates.34Bruce Berman, “Cost and Sources of Global Intellectual Property Theft Include China and the U.S.,” IP CloseUp, Close Up Media, June 23, 2020, https://ipcloseup.com/2020/07/23/cost-and-sources-of-global-intellectual-property-theft-include-china-and-the-u-s/.

- State actor: Such actors have the resources and capabilities to conduct nuanced and sophisticated cyber operations. Although the most prominent state actors targeting the MTS are Russia and China, both Iran and North Korea have proven capable of attacking numerous industrial sectors internationally. These operations normally work to advance strategic goals. There is no international consensus on a definition of “an act of war” in cyberspace and, therefore, it is unclear how defense treaties in traditional spaces influence hostile activities in cyberspace.

While an understanding of the distinctions among threat actors can be useful in considering how to protect specific systems, a strict categorization of any given cyberattack is often difficult because the lines differentiating these actors blur during any dynamic event. Attribution is often a challenging and lengthy process, and results can sometimes be tentative at best. Many criminal organizations in cyberspace, for example, have nation-state sponsors yet their actions are not considered state-sponsored.

Attackers have their own motivations, levels of capability, technological and financial resources, opportunities, time frames, and intents. The primary threat actors that have demonstrated a high capacity and willingness to conduct operations against the MTS and related critical infrastructure sectors fall within two categories: cybercriminals and state-sponsored actors. There are thin boundaries between these categories, given that some state-sponsored groups also operate within well-known cybercriminal networks.

The main focus of cybercriminals is most often monetary gain. They target well-known organizations with large attack surfaces, prey on employees’ lack of cyber awareness, and aim for large monetary rewards. To accomplish these ends, ransomware has become one of the most common and public forms of cyberattacks against MTS targets. Ransomware is used to paralyze a victim organization by encrypting its data and requesting a ransom, often to be paid into a pseudonymous cryptocurrency wallet. Most ransomware attacks are conducted by criminal organizations for their own profit, or to fund criminal and terrorist activities in conventional space. Some other monetary motivations include reselling access to the infrastructure, information obtained, or compromised computers on the darknet, a network using the Internet that requires permission or special software.

Cyberespionage operations targeting the maritime community also are common, primarily in the form of intelligence gathering and Internet Protocol (IP) theft. Cyberespionage represents a middle ground of activity that can be valuable for both criminals and state actors. In March 2019, for example, Chinese state-sponsored hackers reportedly targeted universities around the world, as well as the US Navy and industry partners, in order to steal maritime technology.35Emily Price, “Chinese Hackers Targeted 27 Universities to Steal Maritime Research, Report Finds,” Fortune, March 5, 2019, https://fortune.com/2019/03/05/chinese-hackers-targeted-27-universities-to-steal-maritime-research-report-finds/. China also has an ownership and/or operational presence at dozens of major ports around the world, providing a wide capability for information gathering on ports, vessels, and cargoes. Obtaining this type of access to MTS infrastructure can provide information of strategic significance regarding MTS cyber-physical security, information-system vulnerabilities, and operational information. Furthermore, adversaries may consider breaching a network using zero-day attacks to maintain persistent access to MTS networks to affect or influence the infrastructure operations at the right time.36To the reader, the term zero-day (also known as 0-day) refers to cyberattacks on a software vulnerability before developers find and fix it.

More sophisticated, state-sponsored attacks are just starting to find their way into the MTS, with incidents such as the May 2020 cyberattack by Israel on Iran’s Shahid Rajaee port in Bandar Abbas in response to Iran’s cyberattack on Israel’s water-supply system the previous month.37Ronen Bergman and David M. Halbfinger, “Israel Hack of Iran Port Is Latest Salvo in Exchange of Cyberattacks,” New York Times, May 19, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/19/world/middleeast/israel-iran-cyberattacks.html. Directed spoofing and jamming attacks on global positioning, navigation, and timing (PNT) systems by Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea are additional threats affecting the MTS as well as other transportation sectors.

Framing the challenge

It is imperative to establish at the outset that there is no silver bullet for maritime cybersecurity. A history of old shipboard technology has been retrofitted to an era of interconnectivity, which has created a fractured and vulnerable maritime environment.

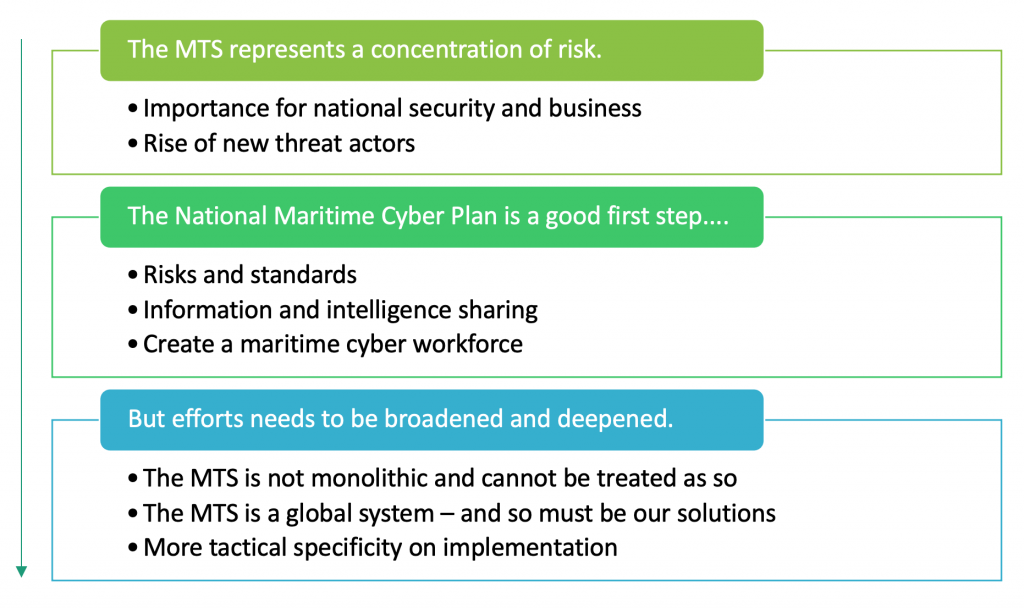

This report is intended to deliver a more complete and operational plan to better protect the MTS by focusing on building upon, broadening, and deepening the priorities put forward by the NMCP. The US government took an important first step in December 2020 when it released the National Maritime Cybersecurity Plan.38National Maritime Cybersecurity Plan to the National Strategy for Maritime Security, Office of the White House, 2020. The plan aims to “buy down the potential catastrophic risks to national security and economic prosperity caused by MTS operators’ increasing reliance on IT and OT, while still promoting maritime commerce efficiency and reliability.” To achieve this goal, the plan focuses on three key principles: risks and standards, information and intelligence sharing, and creating a maritime cybersecurity workforce. The plan represents a significant step in the right direction and calls attention to many of the critical risks outlined in this report. However, it lacks specificity on how to implement these three principles.

This report started by highlighting both the significance of the MTS and some of the most common and consequential threats to the MTS. Now it pivots to discuss major drivers of risk to the MTS and three maritime life cycles—ships, ports, and cargo—and the key programs, vulnerabilities, and stakeholders in each. These sections are explicitly intended to extend the NMCP and identify areas of risk and potential progress for policy makers and industry. The final section builds on the points of leverage identified in these three life cycles and offers specific recommendations to the United States, US allies, and the private sector to cooperatively reduce and better manage the system’s cybersecurity risks.

Explore the full report

This Introduction is part of a larger body of content encompassing the entirety of Raising the colors: Signaling for cooperation on maritime cybersecurity— use the buttons below to explore this report online.

The Atlantic Council’s Cyber Statecraft Initiative, within the Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security, works at the nexus of geopolitics and cybersecurity to craft strategies to help shape the conduct of statecraft and to better inform and secure users of technology.

Related content

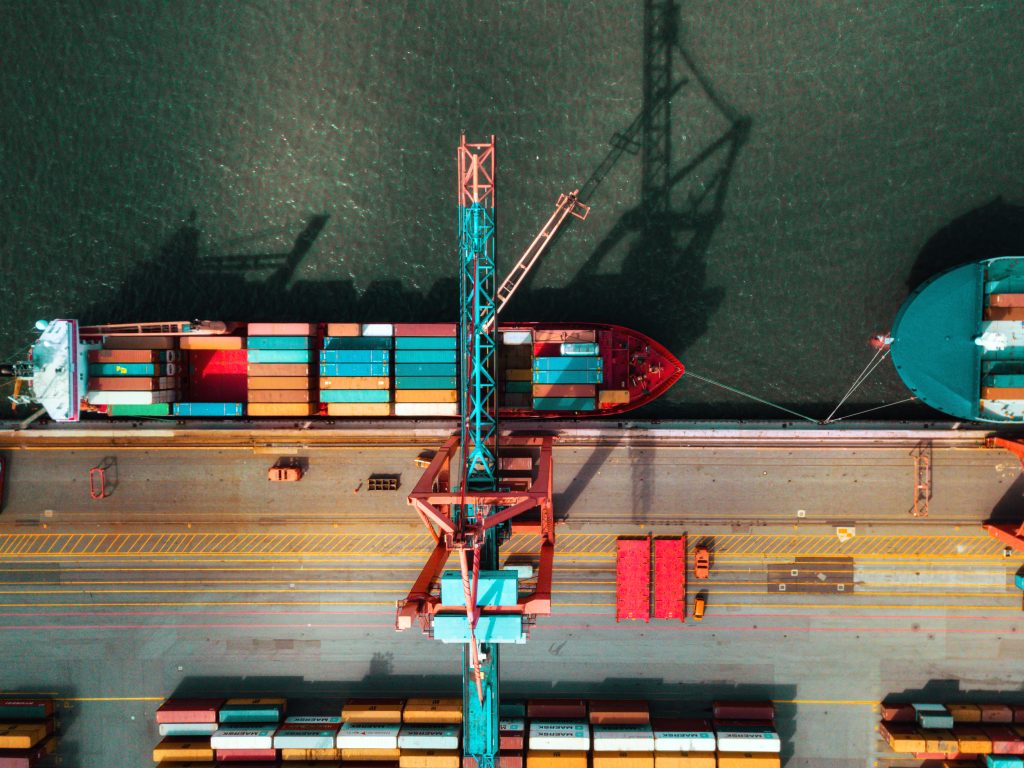

Image: Container ship leaving port.