Raising the colors: Signaling for cooperation on maritime cybersecurity

Executive summary

Few industries are as critical to the global economy as the maritime transportation system (MTS), which is responsible for facilitating the safe transport of seafaring passengers and, critically, the vast majority of international trade. The efficient operation of the MTS is at risk, though, as the industry is increasingly vulnerable to cyber threats. In 2020, cyberattacks targeting the MTS increased by 400 percent over the span of a few months.1“Maritime Industry Sees 400% Increase in Attempted Cyberattacks Since February 2020,” Security magazine, October 20, 2020, https://www.securitymagazine.com/articles/92541-maritime-industry-sees-400-increase-in-attempted-cyberattacks-since-february-2020. Perhaps no incident better illustrated the sector’s cyber vulnerability than when the MTS’s principal international governance body, the International Maritime Organization (IMO), suffered a “sophisticated cyberattack” that took down its web-based services on September 30, 2020.2Catalin Cimpanu, “UN Maritime Agency Says It Was Hacked,” ZDNet, October 06, 2020, https://www.zdnet.com/article/un-maritime-agency-says-it-was-hacked/.

The US government began to address the shortfalls in the sector’s cybersecurity by releasing the National Maritime Cybersecurity Plan (NMCP) in December 2020. Like many first steps, the plan was more like a road map than an implementation plan, despite initiating several useful lines of effort.3Nina A. Kollars, Sam J. Tangredi, and Chris C. Demchak, “The Cyber Maritime Environment: A Shared Critical Infrastructure and Trump’s Maritime Cybersecurity Plan,” War on the Rocks, February 04, 2021, https://warontherocks.com/2021/02/the-cyber-maritime-environment-a-shared-critical-infrastructure-and-trumps-maritime-cyber-security-plan/. This report builds and expands on these efforts across the complex MTS to present three overarching recommendations for industry stakeholders, as well as policy makers in the United States and allied states, to improve their collective cybersecurity posture within the MTS.

No global supply chain is independent of the maritime transportation sector, and most, in fact, are existentially dependent. The MTS feeds a quarter of US gross domestic product (GDP). Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, commercial shipping moved close to 80 percent of global trade by volume and over 70 percent of global trade by value4“Review of Maritime Transport 2018,” United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) website, https://unctad.org/webflyer/review-maritime-transport-2018.—and postpandemic analyses suggest the sector will recover strongly, even growing by 4.1 percent.5UNCTAD, UNCTAD Review of Maritime Transport 2020 (New York: United Nations Publications, 2020), https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/rmt2020_en.pdf. Beyond this substantial economic value, ports and shipping play a considerable role in projecting US and allied power across the globe.

More than containers and bulk cargo, the MTS is responsible for ships and offshore sites, and land-based terminals that are integral to the security of global energy systems. In 2016, more than 61 percent of the world’s total petroleum and other liquid energy supply moved through sea-based trade.6“World Oil Transit Chokepoints,” US Energy Information Administration (EIA) website, July 25, 2017, https://www.eia.gov/international/analysis/special-topics/World_Oil_Transit_Chokepoints. No other form of transportation can move the sheer volume of goods at the competitive price point available in the MTS.7Business Wire press release, “Global Marine Fuel Market (2020 to 2025)–Featuring Shell, Neste, and BP among Others–ResearchandMarkets.com,” Associated Press, November 30, 2020, https://apnews.com/press-release/business-wire/business-government-business-and-finance-coronavirus-pandemic-oil-and-gas-transportation-energy-industry-0810aa8611ca415a92fe3df728bdff72. With ambitious renewable-energy targets being set by states like the United States,8Brady Dennis and Juliet Eilperin, “Biden Plans to Cut Emissions at Least in Half by 2030,” Washington Post, April 20, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-environment/2021/04/20/biden-climate-change/. the actors in the MTS will play a key role in maintaining and expanding renewable facilities. The MTS literally fuels the global economy.

Yet, maritime cybersecurity risks remain underappreciated. The uptick in cyberattacks targeting the MTS includes varieties of attacks familiar to other industries, including ransomware, phishing, and malware such as data wipers, to name a few. In combination with traditional cyber threats targeting information technology (IT) systems, reports of attacks on operational technology (OT), on ships and in ports, increased a whopping 900 percent in a three-year period ending in 2020.9“Maritime Cyber Attacks Increase by 900% in Three Years,” Hellenic Shipping News, July 21, 2020, https://www.hellenicshippingnews.com/maritime-cyber-attacks-increase-by-900-in-three-years/.

Part of the challenge of MTS cybersecurity is the complex structure of the sector. A “system of systems,” the MTS is composed of individual ships, ports and terminals, shipping lines, shipbuilders, Intermodal Transport operators, cargo and passenger handlers, vessel traffic control, maritime administrators, and more. Each system has its own organizational peculiarities and dependencies. Moreover, regulation of the MTS is often indirect because of the interwoven nature of ship management, where many different states and entities might own, lease, sail, register, and crew one ship.

To address this complexity and help stakeholders address the cyber risks impacting the MTS, this report examines three key life cycles—the life of a ship, of a piece of cargo, and of the daily operations of a port—to reveal patterns of threats and vulnerabilities. These life cycles help shed light on a globe-spanning cast of characters. Each life cycle highlights areas of concentrated risk and points of leverage against which policy makers and practitioners can collaborate to take action.

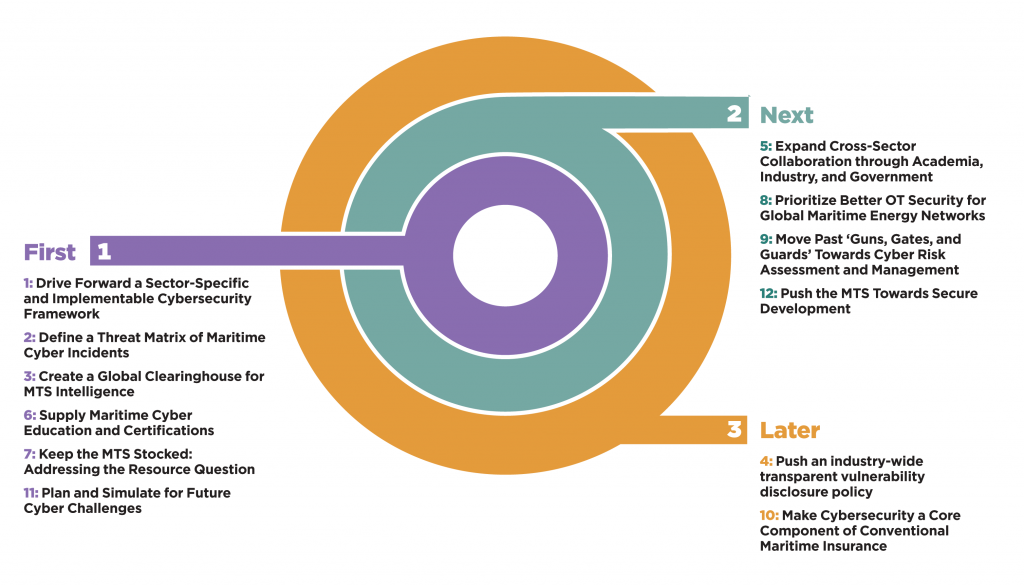

Building on this analysis, the report offers twelve recommendations sequenced as first, next, and later. The first set of recommendations includes six matters to be addressed promptly to secure the MTS. These recommendations need to be prioritized for action because they build directly upon mature preexisting relationships, partnerships, and functions to address key drivers of systemic cyber risk in the MTS. Cybersecurity guidelines and standards fall into this category. Work by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) to develop a framework profile for liquefied natural gas (LNG) operators in the maritime domain demonstrates this maturity and presents a jumping-off point to address the problem of lacking cybersecurity guidelines and standards for the MTS more holistically. The need and willingness across the MTS to improve existing cybersecurity postures are evident, with many differentiated bodies releasing their own guidelines over the last decade and the NMCP outlining it as a key priority going forward.

The next category of recommendations looks to address several areas of concentrated risk in the MTS. However, these actions are built upon points of leverage that are of varying or inconstant levels of maturity. One of the key recommendations in this section seeks to address the issue of insecure system design: how can vendors design systems to be robust in the face of attacks and fail more gracefully? In recent years, and even more so after the Sunburst campaign, there has been a marked increase in initiatives pushing for secure-by-design policies across many sectors, and acquisition bodies are often responsible for enforcing these initiatives. However, the prospect of applying comparable programs to the MTS is wickedly challenging—and although the end result would be extremely beneficial to the ecosystem, it may ruffle some feathers. Many maritime vendors have been producing the same types of systems for decades and may oppose new, mandatory security controls and design requirements. The commercial MTS vendor community, like the MTS itself, is inherently international, requiring standards or design requirements that are aggressively globalized.

Finally, the report makes two later recommendations regarding vulnerability disclosure programs and cyber insurance. Both present differentiated but equally problematic paths toward influencing better cybersecurity in the MTS—chiefly because of misaligned incentives. Vulnerability disclosure programs and mandatory disclosure windows are currently utilized to help better secure ecosystems and specific systems in other industries. A ninety-day mandatory disclosure policy is commonplace in the technology space. However, the quick timelines that often come with these programs can be challenging for maritime actors. Often, a single operator can have hundreds of ships around the globe, and some or many of them may need to address an identified vulnerability: yet no two of the operator’s ships may contain the exact same systems, and consistent access to high-speed Internet zones may be hard to come by. Compared with some other critical infrastructure sectors that can push for a so-called rapid-patch approach, these windows can be unrealistic in the MTS. Implementing an industry-wide mandatory disclosure policy would be a way to draw attention to the problem; however, there would be significant pushback and legitimate questions about whether this policy is realistic.

All twelve of the recommendations put forward by this report are important steps to improve the overall cybersecurity posture of the MTS. By prioritizing actions that are built upon more mature players, protocols, and relationships, this report aims to tackle low-hanging fruit before transitioning to challenging but no less important problems. By following this road map, hopefully, the MTS can work to raise the baseline for cybersecurity and better protect its actors from systemic cyber threats.

Explore the full report

This Executive summary is part of a larger body of content encompassing the entirety of Raising the colors: Signaling for cooperation on maritime cybersecurity— use the buttons below to explore this report online.

The Atlantic Council’s Cyber Statecraft Initiative, under the Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), works at the nexus of geopolitics and cybersecurity to craft strategies to help shape the conduct of statecraft and to better inform and secure users of technology.

Related content

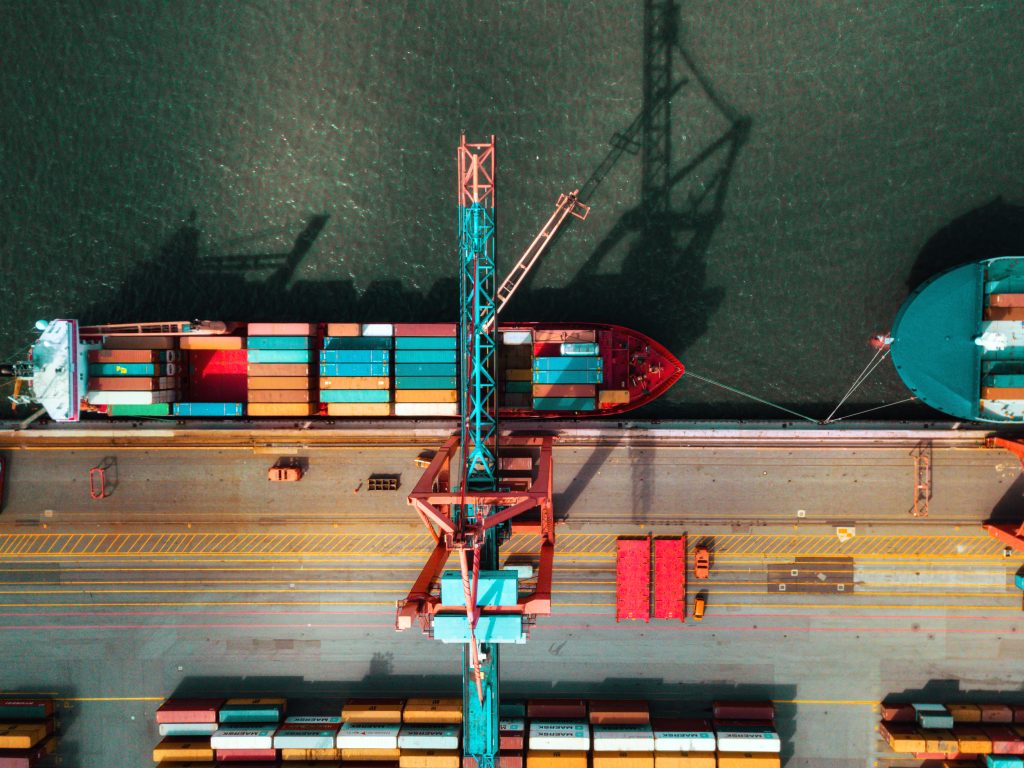

Image: High angle view on cargo crane container terminal photo.