For the US and the free world, security demands a resilience-first approach

This report is the foundational document of the Adrienne Arsht National Security Resilience Initiative (AANSRI) and outlines a bold vision to embed resilience as a core pillar of US and allied security. As crises compound, the initiative calls for investing across individual, institutional, and international levels of resilience to withstand, adapt, and thrive amid disruption.

Acknowledgements

This report is made possible through the vision and generosity of Adrienne Arsht, whose commitment to resilience as a national and global imperative has driven the development of the AANSRI. Her curiosity to explore how individuals build resilience—and why some people withstand adversity while others struggle—has opened new avenues for understanding the role of resilience in shaping societies. This initiative extends that focus, recognizing that resilience is not only an individual trait but a collective necessity, underpinning community cohesion, national security, and international stability.

The author also extends her gratitude to the members of the AANSRI, whose unwavering commitment and generous insights have been instrumental in developing this report over the past nine months. They are leaders and innovative thinkers in their respective fields, and their dedication and collaborative spirit have been invaluable in shaping the future of the initiative’s work. The author also wishes to thank former Atlantic Council staff member Danielle Miller for her efforts in organizing the task force from its inception.

Table of contents

- Prologue: Resilience in Action

- Part 1: Understanding the resilience challenge—and why it matters

- US resilience as a cornerstone of free world strength

- Framing the conversation

- What must democracies be resilient against?

- Complicating factors: The realities undermining resilience

- The need for a more individual-centric approach

- Strategic partnerships are under strain in a shifting world order

- The rapid pace of events is a resilience disruptor

- Democracy is an asset and a challenge for resilience

- Fragmentation of resilience responsibility

- Technology as an enabler—and a threat—to resilience

- The architecture of resilience

- Part 2: Shaping the response

- Conclusion

- Task Force members

- Glossary

Prologue: Resilience in action

At dawn on February 24, 2022, Kyiv woke to explosions. Sirens screamed across the Ukrainian capital. Families rushed into underground shelters. Russia’s full-scale invasion had begun. Although the intelligence community had sounded the alarm, for many ordinary Ukrainians the sound of missiles striking their city was almost unimaginable. Just days earlier, life had felt normal for most of the nation: work, school, errands, birthdays. A full-scale war had arrived in an instant and shattered the illusion of safety and security.

In his apartment, cybersecurity entrepreneur Yegor Aushev took a call from Ukraine’s Ministry of Defense. The official didn’t give him orders, only a request: help us defend the country in cyberspace. Aushev issued a message urging fellow cybersecurity professionals, developers, and ethical hackers to join Ukraine’s digital resistance. By nightfall, thousands had signed up, with Ukrainians and international allies alike offering their credentials, their skills, and their will to help.

Telegram channels multiplied and volunteers in this “IT Army” began to successfully disrupt Russian military communications. This hastily configured task force also helped to defend Ukrainian systems and mapped vulnerabilities across a sprawling and unstable digital battlefield. While tanks advanced on Kyiv and battles unfolded around the country, civilians launched a cyber counteroffensive.

At the same time, neighbors across the capital self-organized. Apartment buildings pooled food and medical students ran first aid training. Teachers arranged online lessons to resist disruption to children’s education. Volunteers repurposed apps into tools for sharing alerts and information.

Kyiv’s municipal government adapted at pace. Within seventy-two hours, the city’s public services app (Kyiv Digital) was reprogrammed to provide real-time air-raid alerts, directions to shelters, and updates on pharmacy supplies. Local authorities coordinated fuel deliveries and waste collection under bombardment. Officials rerouted power and protected infrastructure with the knowledge that help might not come for days.

Nationally, the government did not break. Thanks to pre-invasion decisions, Ukraine’s critical digital infrastructure had already been migrated to secure cloud servers through partnerships with Amazon and Microsoft. Ministries continued to function, the parliament adapted, and the cabinet met in bunkers. President Volodymyr Zelenskyy refused evacuation. Instead, he remained, appearing on camera night after night, anchoring both morale and state legitimacy. Many citizens immediately stepped forward to join the military response, at great personal risk and often without any prior training.

Outside the country, the response accelerated. Following a pre-invasion declaration of support, the United Kingdom deployed anti-tank missiles, logistics support, and intelligence to assist with Ukraine’s defenses. The United States quickly authorized support in the form of anti-aircraft systems, small arms, and ammunition, as well as critical intelligence support. Estonia provided cyber intelligence and expertise, Polish nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) provided medical care and food at the border, and California provided satellite internet. Drones came from Turkey thanks to some prior planning, and refugee support came from Germany, among other nations. Coordination was messy, but allies were leaning in quickly.

Ukraine’s defense in those first weeks did not rely solely on weapons or walls. It was held together by a living system of resilience: the foresight of national institutions, the agility of local government, the improvisation of communities, the solidarity of international partners, and—most critically—the resolve of individual citizens and communities who stood up when nothing was certain.

When the missiles came, Ukraine adapted and withstood, refusing to collapse. The shock and chaos of war in our own neighborhoods are inconceivable to most of us, but what if our communities wake up to a crisis on a scale we have never experienced? We have a crucial opportunity to learn lessons from those who have shown us what resilience in action truly means. They have shown us that resilience does not begin at the point of crisis. It begins in policy decisions made years earlier, in drills conducted without headlines, in the wiring of institutions, in civic trust, in practiced autonomy, and in the mindsets and resilience of ordinary people. We all have roles to play.

Part 1: Understanding the resilience challenge—and why it matters

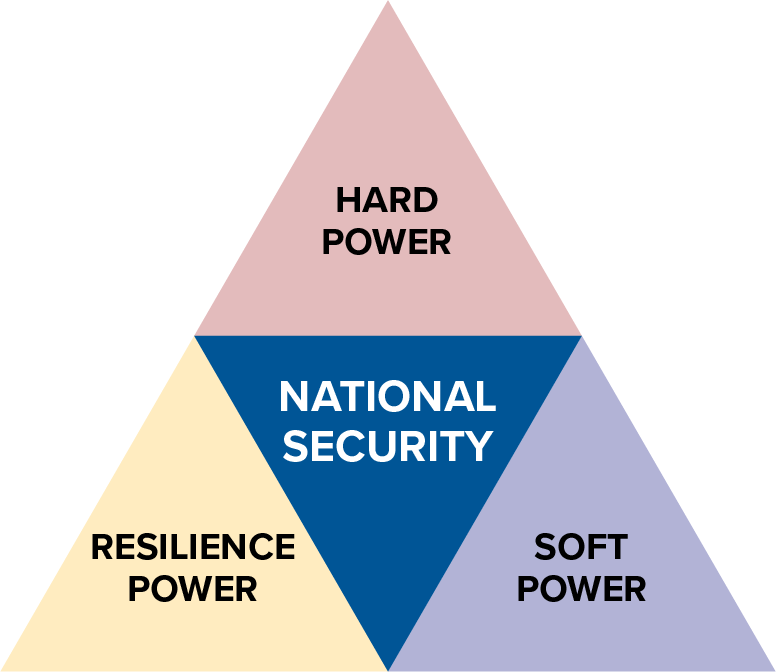

Resilience is an essential—yet often publicly underappreciated—element of national security. Public discourse often centers on deterrence, diplomacy, military strength, and intelligence capabilities. However, emerging and persistent threats—from cyberattacks and climate change to pandemics and acute natural hazards—have revealed significant gaps in national and international resilience, pushing the topic much further up the agenda. Resilience, or “resilience power,” is the foundation on which “hard power” and “soft power” rest. Without these elements, a nation is exposed, and its broader security strategy weakened.

The 2017 US National Security Strategy contains six references to resilience, compared with thirty-six to defense. By the release of the 2022 US National Security Strategy, there were twenty-nine references to resilience compared with thirty-one to defense, reflecting the growing importance of the topic. It’s clear that democracies are increasingly seeing the need to anticipate, endure, and bounce forward.

Despite the growing focus on resilience in national security and policy discussions, too little attention has been paid to the factors that enable individuals to develop and sustain resilience. Governments often prioritize infrastructure hardening and institutional preparedness while neglecting the human element. Along with a top-down approach, the United States must do more to ensure that citizens are psychologically, socially, and economically equipped to endure, and emerge well from crises. Without addressing these individual-level factors, broader resilience and national security strategies risk failing their most important responsibility: to safeguard citizens. The AANSRI will look to redress this balance, advocating for increasing focus and attention on this vital area of resilience work.

National security strategies are valuable opportunities to survey the risk landscape and chart a direction for the future. Yet in a world where specific threats are difficult to predict, such strategies can quickly feel outdated or overtaken by events. A resilience-first approach offers greater adaptability. Rather than focusing solely on defining threats and prescribing bespoke solutions, it equips nations, communities, and individuals to build the capacity to anticipate disruption, absorb shocks, and adapt to rapidly changing circumstances. It demands much more effort to close the vulnerabilities that adversaries seek to exploit. And it embraces uncertainty, enabling a more dynamic and enduring form of security.

The COVID-19 pandemic, the increasing frequency of natural disasters, economic shocks, the rise of disinformation, and state-sponsored cyber and sabotage operations have demonstrated that resilience is not just about recovering well but about proactively reducing risks and ensuring the continuity of society’s essential functions. Inaction in resilience building equates to a tacit acceptance of risk. When governments, institutions, or communities delay or deprioritize resilience work, they are accepting the inevitability of system stress and possible failure. Inaction is not a neutral position but a strategic decision to accept the full impact and cost of disruption rather than mitigate it. There is much more the US government and civil society could do in all areas of society to set citizens up for success.

Governments, businesses, and communities must integrate resilience into decision-making at all levels. This report argues that resilience should be viewed not as a static state but as an evolving “resilience power” capability influenced by investment, governance, technology, and the will of citizens.

“Resilience is the ability of individuals, societies, and systems to anticipate, withstand, recover from, adapt to, and bounce forward from shocks and disruptions.”

– AANSRI task force

US resilience as a cornerstone of free world strength

A strong and sovereign United States, alongside a secure and stable free world, begins with resilience. In an era of intensifying geopolitical competition, economic uncertainty, and evolving security threats, democratic nations must ensure they can withstand, adapt to, and recover from crises—whether in the form of cyberattacks, supply chain disruptions, economic coercion, or natural disasters. Resilience is about ensuring that nations retain the ability to govern, defend, and prosper under pressure.

Collective resilience among democratic allies is what protects shared values, upholds open societies and economies, and ensures that no single crisis can fracture the international order. Without it, fragility in one system or nation can have a compound effect.

For the free world, including the United States, this imperative aligns with a belief that security begins at home but extends beyond borders. Just as energy independence strengthens economic sovereignty, resilience independence—the ability of nations to sustain themselves without reliance on adversarial powers (for example, on China’s technology)—fortifies the free world’s collective strength.

Prioritizing domestic resilience means ensuring that US communities, businesses, and infrastructure can function amid crises without excessive reliance on federal intervention. At the same time, reinforcing resilience across the free world strengthens US national security, ensuring that allies and partners are not weak links that adversaries can exploit to undermine US strength.

This report presents a framework for resilience that is rooted in self-reliance, economic strength, and strategic partnerships: a vision that places US security and prosperity at the forefront while reinforcing the stability of democratic allies. In an era in which adversaries seek to exploit vulnerabilities, resilience must be a specific pillar of national power, alongside economic competitiveness, soft power, and military superiority. A resilient free world is a strong free world, and a United States that leads on resilience will be more secure, more prosperous, more influential, and more prepared for the challenges ahead.

Back to top

Framing the conversation

The United States and democracies worldwide are already achieving much on the resilience agenda, with a lot of mutual learning between friends and allies. The AANSRI task force has not sought to describe all the existing activity here. Instead, its experts have looked for areas of program work that will add value for governments and practitioners already working hard to tackle these complex challenges.

The AANSRI will provide a center of new thought leadership on resilience issues, from the role of the individual up to international collaboration. This report will set out some of the avenues of research and practical policy generation that the initiative can undertake in the coming months and years.

Back to top

What must democracies be resilient against?

In today’s volatile security environment, it is difficult to make specific predictions about the future. But looking at some trends and the trajectory of events can help to determine a broad set of assumptions about the future risk landscape that democracies might face.

To ground the initiative’s discussions and planning, the task force identified three fundamental assumptions. These are not all theoretical constructs; in some cases, they reflect real and current challenges that are already shaping the geopolitical landscape.

These assumptions are “best judgments,” and they provide the initiative with a basis for planning. Because the potential breadth of resilience activities is vast, it will be important to prioritize work streams to achieve maximum impact, with the understanding that the initiative will need to adapt to and address unexpected shocks and developments.

Democratic societies are persistently targeted through non-military aggression

Hostile state and non-state actors are engaged in sustained, non-military aggression against democratic nations. These threats take multiple forms, including

- cyber campaigns targeting critical infrastructure, government systems, and financial institutions;

- economic coercion and trade disruptions designed to weaken national economies and strategic industries;

- supply chain manipulation that creates dependencies on adversarial nations in key sectors such as technology, rare earth materials, and pharmaceuticals; and

- influence operations, misinformation, and disinformation, undermining public trust in institutions and disrupting social cohesion.

The United States and its allies face a growing risk of military conflict and high-impact domestic threats

There is real potential for democratic societies to become involved in a military conflict that escalates beyond regional theaters. If this occurs, adversaries will likely target civilian and domestic environments, not just military assets. Scenarios could include

- cyber or kinetic attacks on financial systems, energy grids, or water supplies;

- nuclear or non-conventional threats creating widespread panic and disruption; and

- concurrent and cascading crises, in which a conflict escalates in tandem with economic, technological, or environmental disruptions designed to overwhelm response systems.

Chronic global risks endure and require systemic management

Long-term, non-malicious threats remain equally urgent, requiring resilience efforts that balance acute security risks with persistent global challenges. These include

- climate change driving extreme weather, resource scarcity, and mass migration;

- food insecurity increasing geopolitical instability, migration, and vulnerability in supply chains;

- anti-microbial resistance (AMR) threatening public health and economic stability; and

- future pandemics remaining high-likelihood events, even after the COVID-19 pandemic.

These risks demand sustained investment, active management, and strategic coordination, rather than the reactive approaches often seen today.

A critical dynamic—the simultaneity, interdependence, and multiplicity of risks—cuts across all these domains. In today’s interconnected world, crises rarely occur in isolation. Instead, societies must contend with the reality of multiple shocks unfolding at once, compounding one another in complex and unpredictable ways. A cyberattack might coincide with an extreme weather event; a disinformation campaign might amplify the impact of a public health emergency. These overlapping disruptions can strain response systems, compete for resources and attention, and overwhelm traditional models of governance built to handle sequential crises, potentially further eroding public confidence in these institutions. Therefore, resilience planning must assume the likelihood of compound and cascading events.

These national security risks are not distant concerns. They can shape the daily realities of individuals, families, businesses, and communities. Democratic societies are already being tested in real time by natural hazards, adversary attacks, and economic shocks. Developing resilience is not just a matter of preparing for worst-case scenarios, but an urgent and ongoing mission to safeguard the stability, security, and prosperity of societies.

Complicating factors: The realities undermining resilience

The three risk scenarios above reflect the landscape of risk that the task force anticipates over the coming months and years. However, these baseline scenarios do not account for a range of additional dynamics that increasingly complicate resilience building. These include a lack of engagement with the resilience of the individual, the instability of strategic partnerships, the accelerating pace of crises, the challenges of operating within a democratic system, and technological advances. These factors make it more difficult for governments and institutions to build sustainable, forward-looking resilience strategies.

Back to top

The need for a more individual-centric approach

While resilience at the national and international levels is crucial, the capacity of individuals to withstand and adapt to crises forms the foundation of a resilient society. Yet, individual resilience is shaped by deeply personal factors (psychological, social, economic, environmental, and physical) that vary widely across populations. People with strong support networks, stable employment, and access to healthcare might be better equipped to endure crises, while those facing financial hardship, social isolation, or chronic stress might be more vulnerable.

The uneven distribution of these enablers means that resilience is not just a question of individual nature or willpower but is significantly influenced by external circumstances that shape people’s ability to respond to crises and trauma. Early childhood experiences, education, community ties, and exposure to adversity are influential in determining resilience outcomes. Early-life trauma, for instance, can weaken an individual’s ability to cope with later crises, while strong social bonds and access to mental health support can enhance recovery and adaptability. Intergenerational and historical trauma—such as that experienced by communities affected by slavery, colonization, or displacement—can shape stress responses across generations, influencing both psychological and biological resilience. Genetic and epigenetic factors, which affect how genes are expressed in response to environmental stressors, might also play a role in how individuals adapt to adversity. These insights suggest that resilience is not simply an innate trait but a skill that can be cultivated through targeted interventions at individual, community, and policy levels.

The resilience of those individuals at the front line of security, safety, and democratic free speech is equally vital. National security professionals, military and intelligence officers, diplomats, medical professionals, and journalists all operate under intense pressure and often deal with complex and harrowing issues. Their capacity to withstand and manage psychological strain is essential for both their own well-being and the effectiveness of their institutions in protecting people. A truly resilient nation must invest in the resilience of these professionals by understanding their lived experiences and ensuring they are supported to remain well, capable, and committed for the benefit of all.

Despite the growing focus on resilience in national security and policy discussions, the AANSRI will examine the factors that enable individuals to develop and sustain resilience over time. Governments often prioritize infrastructure hardening and institutional preparedness while neglecting the human element of ensuring that citizens are psychologically, socially, and economically equipped to endure crises. Without addressing these individual-level factors, broader resilience strategies risk failing the very people they are meant to protect.

Back to top

Strategic partnerships are under strain in a shifting world order

The international alliances that once provided stability and predictability in security planning are now under increasing strain. Shifting political priorities, economic realignments, and growing strategic divergence among US allies and partners make it harder to maintain long-term resilience efforts. While multilateral institutions such as NATO, the Group of Seven (G7), the World Health Organization (WHO), and the United Nations (UN) remain crucial frameworks for cooperation, internal divisions and misaligned national interests have weakened their ability to coordinate resilience efforts across borders. For example, in early 2022, efforts to pass robust resolutions in the UN to enable greater humanitarian access and protection in Ukraine were watered down or blocked by Russia as a permanent member of the Security Council.

At the same time, adversarial states are actively exploiting fractures between allies. Cyber aggression, economic coercion, and covert influence campaigns are being used to drive wedges between strategic partners, making collective resilience more difficult. This is particularly evident in supply chain vulnerabilities, as dependencies on adversarial nations in key sectors such as critical minerals, semiconductors, and energy create potential leverage points for disruption. These pressures are playing out across multiple strategic relationships.

The Alliance, while still strong, is facing increasing policy divergence on economic security, trade, and technology governance. NATO, traditionally the bedrock of transatlantic security, is experiencing calls from both sides of the Atlantic to increase European defense burden-sharing, including an emphasis on national resilience, as found in Article 3 of the founding treaty. As Europe provides for more of its own defense, national resilience among NATO members will only become more critical for individual and collective security. In the Indo-Pacific, the Quad (Australia, India, Japan, and the United States) continues to coordinate efforts in some areas, but there will inevitably be differences in priorities for resilience building. Meanwhile, the tangible outcomes of G7 efforts to collaborate on key economic security priorities are still unfolding.

Still, US alliances have weathered difficult challenges in the past and should remain an important component of advancing shared resilience objectives in the future. The crucial question is how to adapt, develop, or reinvent mechanisms to meet current challenges and dynamics.

Back to top

The rapid pace of events is a resilience disruptor

Beyond the challenges of alliance instability, the accelerating speed of crises is outpacing governments’ ability to plan and respond effectively. Geopolitical conflicts, technological shifts, and economic shocks are unfolding at a rate that strains resilience frameworks, which were designed for slower-moving risks.

This challenge is further compounded at the international level, where multilateral institutions and cooperative mechanisms often operate at a pace ill-suited to the urgency of modern threats. Organizations such as the UN, NATO, and the G7 play important roles in resilience coordination, but their decision-making processes are frequently constrained by consensus requirements, political divergence, and bureaucratic inertia. As crises become more complex and move faster, these institutions risk becoming irrelevant unless they evolve to match the speed and scale of emerging risks.

To remain effective, international resilience efforts must become more agile, allowing for faster decision-making, more flexible coalitions, and the integration of bilateral initiatives when multilateral consensus is too slow or ineffective. Without meaningful reform, traditional mechanisms of global collaboration will struggle to provide the resilience support that nations require, forcing states to seek alternative frameworks that can respond at the necessary speed and scale.

Back to top

Democracy is an asset and a challenge for resilience

Democratic systems have distinct advantages for building resilience. The decentralized nature of power allows responsibility to be distributed across government, civil society, and the private sector, making crisis responses more flexible and adaptable. Local and regional actors can take independent initiative, ensuring that resilience efforts are not dependent on a single point of failure. NGOs are encouraged to play a critical role in local resilience and are supported in these efforts.

The free flow of information is also a huge asset. Open discourse, independent media, and transparency enable early risk detection and effective crisis response. Unlike authoritarian regimes that suppress inconvenient truths, democracies encourage debate and learning, helping refine strategies over time. Public trust is also a critical asset. In democratic systems, citizen engagement in decision-making tends to foster higher trust and legitimacy, which in turn supports voluntary compliance with emergency measures and long-term recovery. Autocratic systems may ensure compliance through fear and force, democracies build resilience through consent.

Case study: The Thames Barrier

Democracies can and do succeed at long-term resilience planning when the risk is well understood and a political consensus and will to act are developed. The Thames Barrier in London, constructed between 1974 and 1984, is a great example of sustained action to reduce risk over time. This movable flood defense was developed in response to the devastating North Sea flood of 1953, which claimed more than three hundred lives in the United Kingdom. The barrier protects 125 square kilometers of central London, including critical infrastructure and £321 billion worth of residential property, from tidal surges and storm floods.

This trigger event galvanized politicians across the spectrum, with successive Labour and Conservative governments depoliticizing the issue and keeping the project funded and on track. The Thames Barrier’s success stems from transparent governance, public accountability, and adaptive planning. In contrast to autocratic systems, where rapid implementation can overlook long-term sustainability, the Thames Barrier showcases how democratic processes and political leadership emphasizing stakeholder engagement, transparency, and adaptability can lead to enduring and effective resilience infrastructure.

Democracies must find new ways to trade on the strengths of systems to improve resilience, while balancing electoral accountability with long-term resilience strategies, ensuring preparedness remains a priority despite political turnover.

Fragmentation of resilience responsibility

One of the most significant challenges to resilience is fragmentation, in which responsibility for managing risks is dispersed across multiple institutions, sectors, and levels of government with limited coordination. In many democracies, resilience-related functions such as cybersecurity, disaster response, infrastructure protection, and countering disinformation are divided among government agencies, private companies, and local authorities—often with misaligned priorities, unclear responsibilities, and limited mechanisms for collaboration. Although largely unavoidable, this lack of unity can make it harder to anticipate, prevent, and respond effectively to crises.

Beyond government, much of a nation’s resilience power resides in civil society, businesses, and local communities. Private-sector actors own and operate the majority of critical infrastructure, yet their risk calculations are often driven by market forces rather than national security imperatives. Meanwhile, local governments and community organizations are frequently on the front lines of crisis response but might lack the necessary resources, authority, or integration into national resilience strategies. These silos can slow decision-making and create vulnerabilities that adversaries can exploit.

To overcome this, the United States needs a fundamental shift in how resilience is structured and managed. Rather than just allocating responsibilities, governments must activate all layers of the resilience architecture supporting them to interact in ways that reinforce and enable one another. This means

- ensuring vertical integration, so that resilience efforts at the national, regional, and local levels are aligned and mutually reinforcing;

- strengthening horizontal coordination across sectors, ensuring that critical industries, government agencies, and civil society organizations work in concert rather than in isolation; and

- creating mechanisms for shared awareness and adaptive learning so that resilience actors at all levels can anticipate emerging threats, adjust strategies in real time, and support one another’s efforts.

There is precedent for such robust collaboration. Launched in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, Operation Warp Speed (OWS) brought together federal agencies, military logistics, and private pharmaceutical companies to accelerate vaccine development, manufacturing, and distribution. This public-private partnership initiated by the US government in May 2020 overcame bureaucratic and logistical barriers to deliver safe, effective vaccines in record time. The initiative demonstrated how aligning government support with private-sector innovation can rapidly build national resilience in the face of a public health crisis, creating a blueprint for future efforts.

A more interconnected resilience ecosystem is essential to navigating the complex threats of the future. Without it, resilience efforts will remain fragmented, reactive, and vulnerable to disruption.

Case study: The Texas power grid

The devastating 2021 Texas power grid failure was a disaster for the state. In the aftermath of the disaster, the state reported more than two hundred deaths and up to $195 billion in damages. The roots of the failure can be found in Austin’s energy regulation strategy, a unique approach that left it vulnerable to disaster and unable to withstand the shocks of increased demand.

In the 1990s, the Texas state government decided to decentralize its grid, prioritizing a competitive, market-based system of transmission operators and energy retailers. This resulted in lower energy prices for consumers but, with a desire to keep prices low, the companies operating the grid lacked incentives to invest in maintenance, upgrades, and general oversight. At the height of the crisis, 4.5 million customers were without power, and the grid was only four and a half minutes away from total failure.

In the lead-up to the crisis, authorities flagged that the grid was not sufficiently winterized and lacked waterproofing that would allow it to withstand snow and ice. Further exacerbating the crisis, the Texas grid operates independently of the power grids of other states. This is by design, minimizing the amount of federal oversight and regulation required, but also meant that the Texas grid was unable withstand the impacts of the storms.

Technology as an enabler—and a threat—to resilience

Technology presents both a challenge and an opportunity. While digital advancements can enhance resilience, they also introduce new vulnerabilities, from cyber threats to the rapid spread of misinformation. Digital advancements can bolster preparedness and response by enhancing early warning systems, improving crisis coordination, and securing supply chains. But they also introduce vulnerabilities that can undermine these efforts.

Cyber threats pose one of the most immediate challenges to national resilience. The 2021 ransomware attack on the Colonial Pipeline disrupted fuel supplies across the US east coast and highlighted the susceptibility of critical infrastructure to cyber threats. And these threats are evolving under the direction of hostile states. China has been using advanced technologies and persistently attacking critical national infrastructure in democracies, specifically targeting communications, energy, and transportation systems. China’s Volt Typhoon operation has successfully compromised a range of US infrastructure. And China is not alone in seeking to exploit cutting-edge technology to its advantage. For example, recent reports indicate that North Korea has established Research Center 227, a unit dedicated to developing offensive hacking technologies and programs, including those leveraging artificial intelligence (AI).

Looking ahead, the resilience challenges posed by quantum computing could be even more profound. Advances in quantum technology have the potential to break current encryption standards, threatening the security of financial systems, government communications, and sensitive data. Democracies are already working on post-quantum cryptography to counter this risk, but the transition will take time, and adversarial actors could exploit weaknesses before defenses are fully in place.

Beyond the digital sphere, bioengineering and robotics introduce entirely new dimensions of risk. Synthetic biology could be used to develop engineered pathogens, blurring the line between natural pandemics and deliberate biological threats. At the same time, advances in autonomous systems and robotics could revolutionize warfare, raising concerns about weaponized AI-driven systems operating beyond human control. The intersection of these scientific fields—quantum computing, AI, bioengineering, and robotics—presents unknown risks to resilience and national security.

At a more basic level, public platforms and ubiquitous technology can be exploited to undermine resilience and crisis response. For example, the rapid spread of misinformation on social media platforms during crises can erode public trust and complicate effective responses, as seen during the COVID-19 pandemic. Off-the-shelf drone technology has disrupted air travel and caused huge concern about reconnaissance and even weapon deployments against domestic targets.

To build true resilience, it is necessary to mitigate today’s technological threats, anticipate how emerging technologies will shape the future risk landscape, and fully understand how technology shapes both strengths and vulnerabilities.

Back to top

The architecture of resilience

Resilience is a multi-layered ecosystem requiring participation at different levels of society, from individuals and communities to states and the international order. Each layer plays a distinct role in absorbing, adapting to, and recovering from disruptions, and resilience cannot be truly effective unless it is developed holistically across these levels.

At the individual level, resilience is shaped by psychological, social, economic, and genetic factors that determine how people respond to crises. Individuals with strong support networks, adaptive mindsets, and economic stability are better equipped to withstand and recover from shocks. However, individual resilience does not exist in isolation; it is influenced by the structures and resources available within communities and broader systems.

Community resilience builds on this foundation by fostering social cohesion, local preparedness, and collective problem-solving. Strong communities serve as the first line of response in crises, providing informal support networks that complement institutional responses. Yet, communities require policy support, infrastructure, and investment to maintain their ability to function under stress.

At the local and state levels, resilience depends on governance structures, coordination mechanisms, and resource allocation. Effective local resilience requires a well-integrated approach that ensures cities, states, and national authorities work together to mitigate risks. However, governance fragmentation often weakens resilience efforts, with responsibilities split across institutions that might lack clear coordination. This is particularly evident in crisis response scenarios, in which local authorities—without national support—might lack the capacity or funding to act swiftly.

National resilience integrates all these layers, ensuring that resilience is not only built at the community level but is also embedded in national security strategies, economic policies, and infrastructure planning. This level of resilience requires governments to prioritize long-term risk reduction, balancing investment in critical infrastructure, cybersecurity, and strategic reserves while maintaining the agility to respond to immediate crises. However, as discussed earlier, short-term political incentives often hinder sustained investment, making national resilience a complex challenge.

Finally, international resilience reflects the reality that no nation operates in isolation. Global crises—whether pandemics, cyberattacks, or geopolitical conflicts—demand coordinated responses across borders. Resilience at this level is shaped by alliances, multilateral cooperation, and shared risk-management strategies. However, geopolitical tensions, economic competition, and diverging national interests often limit the effectiveness of global resilience efforts, making collaboration challenging even when threats are transnational.

All of these layers are interdependent; weakness at any level undermines the resilience of the whole. To create a truly resilient society, resilience must be treated not as a siloed concept but as a structural framework, integrating individuals, communities, governance, national security, and international cooperation into a unified approach to risk and preparedness.

Part 2: Shaping the response

Individual resilience: The foundation of national strength

At the heart of the AANSRI lies a simple truth: a nation cannot be resilient unless its people are resilient. Governments can build strong institutions, invest in infrastructure, and create policies to mitigate risk, but the nation will remain vulnerable if individuals lack the capacity to withstand and adapt to crises. Individual resilience is not only about personal survival; it is the foundation upon which community, state, and national resilience are built. Without it, all other layers of resilience are compromised.

Resilience at the individual level is shaped by several key factors, including psychology, social support, practical security, and genetics. The resilience of the individual is inextricable from community resilience, of which aspects of social network support are covered in greater detail below.

Psychological resilience, which is often described as mental toughness or emotional endurance, determines how well individuals respond to stress, uncertainty, and trauma. Those with naturally adaptive mindsets, problem-solving skills, and emotional regulation are more likely to navigate crises effectively. However, psychological resilience does not develop in isolation; it is strengthened or weakened by social conditions and the availability of practical resources.

Despite the importance of individual resilience, it is often overlooked in national security and policy discussions. Governments tend to focus on macro-level resilience strategies, assuming that institutional strength will translate into societal resilience. But policies, strategies, and emergency plans are only as effective as the people who must implement and respond to them. Without better understanding of, and investment in, the resilience of individuals through education, the United States is missing a vital piece of the puzzle.

A core argument of the AANSRI is that resilience must begin at the individual level. Strengthening individuals strengthens communities—which, in turn, reinforces local, national, and international resilience. This initiative places individual resilience at the center of a national security conversation, recognizing that resilient nations are built from the ground up.

Case study: A national security analyst’s story

For nearly a decade, Maya, a mid-career national security analyst, thrived in a high-stakes federal agency known for its demanding tempo and mission-critical work. Tasked with coordinating real-time intelligence during a rapidly escalating international crisis, she often worked fourteen-hour days in secure facilities, balancing classified briefings, urgent decision-making, and the weight of knowing that lives depended on timely, accurate analysis.

Over time, this cumulative stress began to take a toll. Maya experienced persistent insomnia, emotional detachment, and difficulty concentrating—early signs of burnout she initially ignored. In a field where stoicism is often mistaken for strength, seeking help felt risky. Still, she quietly reached out to her agency’s internal wellness team and was connected with a resilience coach through a pilot program developed for high-performing staff in critical roles.

The intervention proved transformative. Maya learned tools drawn from cognitive-behavioral science to manage stress and improve focus. She also joined a peer support group for national security professionals, in which she could speak candidly about her experiences for the first time. Through structured coaching and informal connection, she reframed her stress response from something shameful to something manageable—and even instructive.

With time and support, Maya returned to her role with renewed clarity and a deeper understanding of what sustainable performance looks like. She became a champion for integrating resilience practices into team workflows—advocating for debriefing rituals and flexible scheduling where possible, and encouraging early-career staff to use the wellness resources she once hesitated to explore.

Maya’s story underscores a core insight from resilience science: it’s not the absence of stress, but the presence of support, skills, and self-awareness that makes the difference. In mission-driven environments such as national security, where the cost of burnout is high and the stigma around seeking help remains, individual resilience is not a luxury—it’s a strategic imperative.

Strong individuals make strong nations: Recommendations for the AANSRI

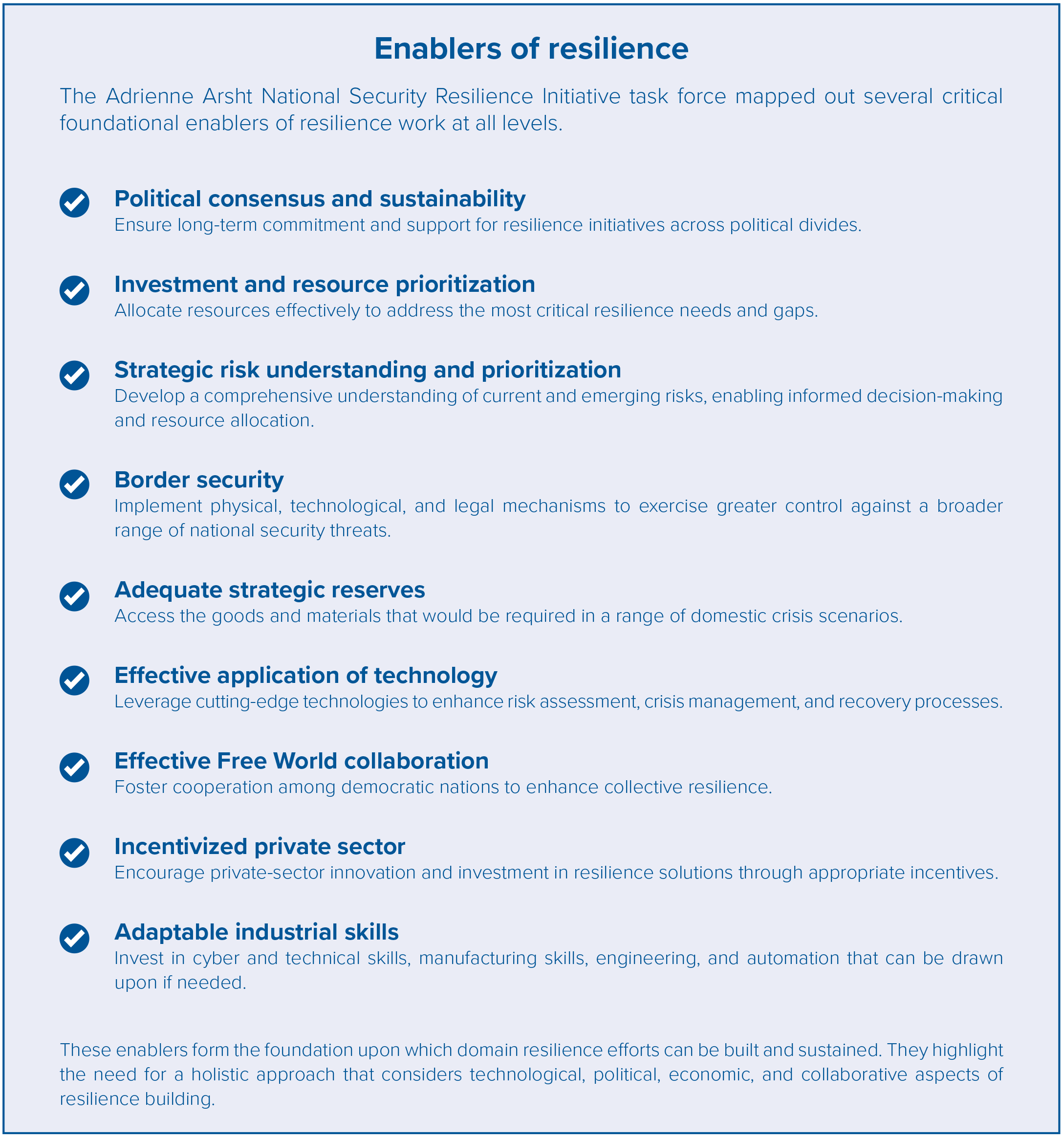

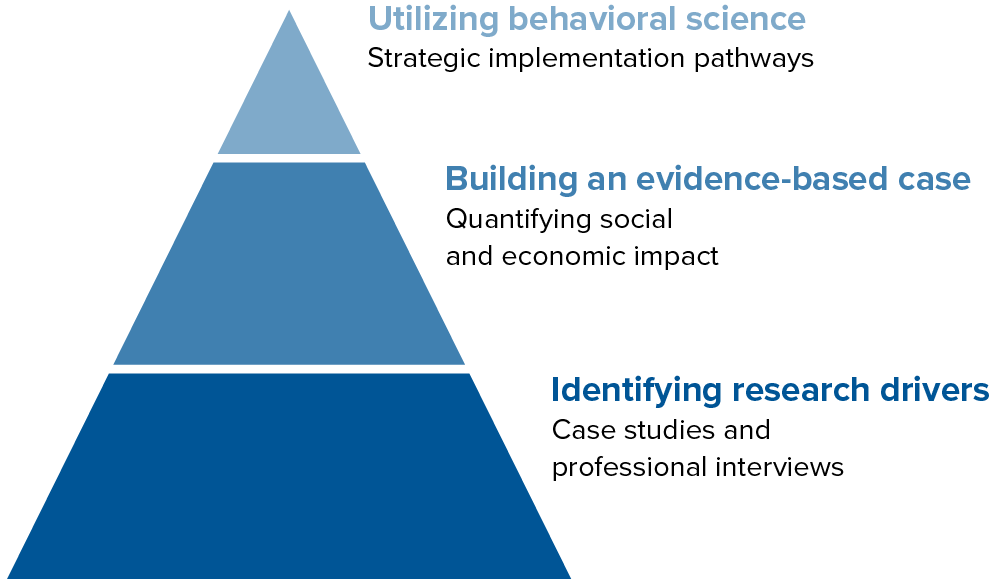

1. Conduct research on the drivers of individual resilience.

- Perform a comprehensive analysis of resilience factors.

- Develop and analyze case studies. Draw from both domestic (US) and international examples to compare resilience-building approaches across different cultural and policy contexts.

- Distinguish between innate psychological traits (e.g., temperament, cognitive flexibility, and genetics) and external social influences (e.g., community, education, and institutional support) that enhance or hinder individual resilience.

- Conduct targeted research interviews with professionals in high-stress fields where resilience is critical. This should include military and intelligence personnel, journalists operating in conflict zones, frontline medical staff (e.g., emergency room doctors, paramedics, and disaster response teams), and humanitarian workers in crisis zones.

2. Build an evidence-based case for individual resilience.

- Quantify social and economic impacts.

- Commission research and economic modeling to assess the cost of low resilience (e.g., increased mental health issues, reduced workforce productivity, and greater reliance on government support in crises) and the economic and social benefits of resilience-building measures.

- Integrate policy, using findings to advocate for policy shifts that recognize resilience as a strategic asset, integrating it into education, workforce training, and public health initiatives.

3. Apply behavioral science to strengthen resilience.

- Analyze cross-sector behavior.

- Examine how behavioral science is used successfully in other policy areas (e.g., health, security, and disaster preparedness) and identify best practices.

- Develop strategic implementation pathways with practical policy recommendations that could be implemented at national and state levels (e.g., public awareness campaigns, resilience education in schools, and workplace stress-management policies) or by private-sector actors, particularly social media companies, to explore how digital platforms could foster resilience-building behaviors rather than exacerbating stress and division.

4. Highlight and elevate the voices of individuals who have been able to bounce forward from adversity to convey the importance of individual resilience to a general audience.

- The AANSRI could produce a Profiles in resilience video series that spotlights individuals in the national security community who have faced significant hardships or experienced especially challenging circumstances in the course of their work. Importantly, this series should aim to highlight the lessons in resilience interviewed participants can draw from those experiences.

Resilient communities: The social core of national security

While individual resilience is the foundation of a resilient nation, communities act as the first line of defense in times of crisis. A well-connected, engaged community can absorb shocks, adapt to disruptions, and recover more effectively than individuals acting alone. Community resilience is built on trust, local leadership, shared resources, and the ability to mobilize quickly in response to emergencies.

Strong communities enhance resilience by providing mutual support networks that supplement government responses. Whether through informal networks of neighbors, faith-based organizations, or structured civil society groups, resilient communities act as force multipliers in times of crisis.

However, communities face significant barriers to resilience, including economic disparities, political disengagement, and lack of local investment. In many cases, the most vulnerable communities are also the least equipped to prepare for, respond to, and recover from crises. Governments often assume that resilience will develop organically. But without deliberate efforts to strengthen community capacity, social cohesion can quickly erode under stress.

Social resilience stems from the networks and relationships individuals rely on in times of crisis. Strong communities, family ties, and support systems act as buffers, reducing the impact of external shocks. Studies on disaster recovery have consistently shown that individuals embedded in cohesive social networks (including digital networks) fare better than those who are isolated.

Resource stability is equally critical. Individuals living in poverty or financial precarity have fewer resources to absorb shocks, whether from job loss, health crises, or natural disasters. This is not just about income; it includes access to education, healthcare, and financial literacy, all of which determine an individual’s ability to plan, adapt, and recover. Local NGOs can play a critical role in meeting the resource gap for less well-equipped individuals. When a crisis manifests at a local level, faith-based organizations and other community groups are often vital in both preparedness and response activities.

Another major challenge is the fragmentation between local initiatives and national policies. While governments might have national resilience strategies, these do not always translate into localized, community-driven preparedness efforts. Effective resilience building requires a bottom-up approach, in which national policies support and empower local leaders, grassroots organizations, and community-driven risk-reduction efforts.

Case study: Hurricane Katrina

Elected government failed to adequately prepare the Gulf Coast for Hurricane Katrina. Combined with uneven recovery efforts, perceptions of resilience shifted the focus toward community-led recovery. Responding to Katrina’s devastation truly took a village—from actor Matthew McConaughey rescuing a local anesthesiologist and fifty stranded pets from a hospital without food or running water for seven days, to community groups uniting to rebuild schools after the storm left only 17 percent of New Orleans schools operational.

Across the Gulf Coast, residents developed strong social bonds, creating resilient communities ready to support each other amid recurring disasters. Today, when storms strike neighboring areas, volunteer groups like the Cajun Navy mobilize swiftly, bringing personal “airboats, duck boats, fishing skiffs, and even kayaks” to perform search-and-rescue missions. These efforts have proven vital, especially when rising waters trap people on rooftops.

One might assume residents of New Orleans and surrounding areas have become hardened after such significant loss, but the opposite has occurred. A profound sense of community support and empathy now characterizes the region, shaping both disaster recovery and everyday interactions. The resilience cultivated after Hurricane Katrina illustrates the extraordinary power of community ties in overcoming adversity.

The role of communities: Recommendations for the AANSRI

1. Develop comparative case studies that examine successful community resilience models from the United States and internationally, identifying key factors that strengthen resilience across different social, economic, and governance contexts.

2. Map vulnerabilities to understand which geographical areas need the greatest additional support from outside.

3. Conduct social research on strengthening community bonds. Explore what fosters strong, connected communities and how these factors contribute to community preparedness (how social cohesion influences readiness for crises), crisis response capacity (how networks mobilize quickly when disasters strike), and long-term recovery (how social ties aid rebuilding efforts and reduce long-term vulnerabilities).

4. Investigate how formal and informal local leadership—such as mayors, faith leaders, neighborhood organizers, and business leaders—supports resilience efforts.

- Focus on which leadership traits and approaches enhance community preparedness and how leadership can be developed and encouraged at a grassroots level.

5. Develop strategic recommendations for state, national, NGO, and private-sector support.

- Assess the most effective forms of external support.

- Identify what state, federal, and NGO interventions are most effective in enhancing community preparedness for emergencies, supporting rapid response and recovery when crises occur, and empowering local communities rather than creating dependency.

6. Maximize impact through financial investment; research where funding and resources should be directed to generate the most significant national impact.

- Assess if investment should focus on infrastructure, training, social programs, or crisis communication systems.

- Understand how financial incentives can encourage community-led resilience projects.

7. Leverage technology for resilience building to bridge the gaps between national direction and community resilience. Explore the role of digital tools and innovations in strengthening resilience, including

- early warning systems and crisis communication platforms;

- social media and community apps for coordination during emergencies;

- data-driven risk assessments to help communities prepare and adapt; and

- the role of information and risk analysis at a community level.

8. Develop tools to facilitate resilience literacy in communities.

- Explore how local communities access and interpret risk information most effectively.

- Study how to promote better risk literacy among residents.

- Investigate what information (and information-sharing structures) would improve local preparedness and response.

Empowering state and local resilience: The operational frontline

Resilience at the local and state levels plays a critical role in connecting community-based preparedness efforts with national security strategies. Local and state governments are usually the first to respond to crises, whether natural disasters, public health emergencies, or security threats. They serve as the operational backbone of resilience, coordinating between federal resources, private-sector actors, and local communities.

However, despite their central role, local and state governments often struggle with fragmented responsibilities, inconsistent funding, and bureaucratic inefficiencies. Many resilience efforts suffer from a lack of coordination between different levels of government, with local and state actors frequently left out of national security planning processes. If resilience is to be truly effective, local and state structures must be better integrated, properly resourced, and empowered to act decisively.

Under President Donald Trump’s administration, there has been a notable shift in disaster preparedness responsibilities from federal agencies to state and local governments. An executive order signed on March 18, 2025, emphasizes that “preparedness is most effectively owned and managed at the state, local, and even individual levels,” thereby reducing the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) direct involvement in disaster preparations. This policy change aims to empower local entities to make infrastructure decisions tailored to their specific needs, leading to more efficient use of resources.

This transition has raised concerns about the capacity of state and local governments to shoulder increased responsibilities without substantial federal support. Critics argue that diminishing FEMA’s role could leave communities vulnerable, especially those lacking the financial resources to invest in necessary infrastructure and preparedness measures. The executive order also calls for revising critical infrastructure policies to better reflect assessed risks, moving away from a generalized all-hazards approach. While this strategy seeks to streamline disaster preparedness, it might also result in disparities in readiness across different regions, depending on their individual risk assessments and resource allocations. New funding gaps resulting from a radical reduction of FEMA could take a long time to fill. State legislatures might not be able to act swiftly, which would incur significant interim risk.

Local and state resilience depends on four key pillars.

1. Coordination and crisis response capacity

- Local and state governments must be able to act quickly and decisively in a crisis. However, many suffer from slow bureaucratic processes, unclear chains of command, and limited autonomy in decision-making. The ability to coordinate emergency response across multiple jurisdictions is essential for resilience.

2. Infrastructure and investment in risk reduction

- Physical and digital infrastructure play major roles in resilience. Roads, energy grids, water systems, and cybersecurity frameworks must be designed to withstand shocks and recover quickly. However, resilience investments often take a backseat to more immediate political priorities, leaving critical infrastructure vulnerable to failure.

3. Legislation and policy support

- Effective resilience building requires strong policy frameworks at the state and local levels. Laws related to disaster preparedness, building codes, emergency funding, and information sharing can significantly enhance local resilience. However, many jurisdictions lack the authority or resources to enforce such policies consistently. For example, it has proved difficult to combat China’s efforts to purchase land near US and allied military bases because, at a local level, there is less access to intelligence or technical capability to identify and manage the risk.

4. Public trust and community engagement

- State and local governments must engage the public in resilience efforts. Without clear communication and public trust, emergency response efforts can face resistance or confusion. Strengthening local resilience means ensuring that citizens understand their role and have confidence in their local leadership.

- Despite their critical role, local and state resilience efforts are frequently underfunded and under-prioritized.

Case study: The Ohio Cyber Reserve

In 2022, Ohio Governor Mike DeWine issued an executive order that directed the creation of a new, cabinet-level position of cybersecurity strategic advisor to guide the state’s cybersecurity efforts across agencies, including the development of the Ohio Cyber Reserve (OhCR). The OhCR was established under the Ohio Adjutant General, the executive branch of the Ohio state government that oversees the Ohio National Guard. The OhCR is an all-volunteer civilian force organized around three missions—assist, educate, and respond—which all make the OhCR an agency responsive to cybersecurity issues around the state. Further complementing Ohio’s resilience to cyber threats was the creation of the Ohio Cyber Integration Center, which sits within the Ohio Adjutant General and coordinates the state’s responses to cyber threats, serving as a central hub and coordination center. These initiatives, alongside the OhCR, all contribute to the state’s cyber resilience. They combine education and awareness with job creation and economic development to create a more resilient Ohio.

Local and state resilience: Recommendations for the AANSRI

1. Map local resilience capacity and governance gaps.

- Complete comparative analysis of local resilience governance. Conduct a multi-region study of how different state and municipal governments structure their resilience planning, funding, and crisis response. Identify best practices and key gaps in preparedness.

- Develop a local-state resilience index. Create a standardized resilience index to measure preparedness, coordination capacity, and recovery effectiveness across different states and municipalities. This could serve as a tool for benchmarking and guiding resource allocation.

2. Design smarter national-to-local resilience strategies.

- Evaluate the 2025 executive order’s impact and analyze the shifting balance of responsibilities from federal to state governments. Determine what practical policy and operational choices would support the drive to “streamline preparedness operations; update relevant Government policies to reduce complexity and . . . enable State and local governments to better understand, plan for, and ultimately address the needs of their citizens.”

- Determine what functions can only be performed at the federal level (e.g., large-scale intelligence and strategic coordination) and where states can take greater responsibility.

- Explore innovative financing models for local resilience. Explore alternative funding mechanisms for resilience projects, including public-private partnerships (PPPs) for infrastructure resilience, municipal resilience bonds, and philanthropic and impact investment strategies to support resilience initiatives.

3. Optimize crisis coordination between state and local authorities.

- Understand lessons from past crisis responses by conducting case studies on successful and failed coordination efforts in state-level crises (e.g., hurricanes, cyberattacks, and wildfires). Identify systemic weaknesses and develop insights into what enables effective coordination.

- Improve intelligence and resource-sharing mechanisms by examining how state and federal agencies can ensure timely information sharing, particularly in rapidly evolving crises (e.g., cyber incidents, coordinated attacks, and energy grid disruptions).

4. Simulate a malicious-origin cascading crisis affecting multiple states. While most crises occur naturally, the Colonial Pipeline cyberattack and other state-backed disruptions highlight the need to study threat-based resilience.

- Develop a two-day resilience simulation. Design and execute a multi-stakeholder exercise engaging federal, state, and local authorities, community organizations, emergency responders, and defense, intelligence, and cybersecurity experts.

- The simulation should test how cascading failures across sectors (e.g., energy, finance, transportation, and supply chains) impact state resilience and what coordination structures are most effective in mitigating impact. Expose any gaps in information sources, system connections, policies and regulations, or practical support.

National leadership: The strategic architecture of resilience

At the national level, resilience is about ensuring that a country’s institutions, infrastructure, economy, and security apparatus can withstand, adapt to, and recover from crises. National resilience is the product of individuals, communities, and local and state efforts that are supported and enabled at the national level. This combined effort is the strategic backbone that enables societies to function under stress, whether facing economic shocks, cyber threats, political instability, natural disasters, or military aggression.

However, governments often struggle to embed resilience into national security strategies in a meaningful way. The challenge lies in competing policy priorities, short-term political incentives, and the difficulty of justifying resilience investments when crises are hypothetical rather than imminent.

As the recent presidential executive order illustrates, much of what needs to be done sits outside of the federal and national government space. As the United States develops a new resilience strategy, it will be important to connect the dots with other areas of national security strategy, policy, and operations. Resilience work requires a fully collaborative and cross-cutting national approach. Understanding and clearly articulating and supporting the relative roles of partners at all layers of the resilience architecture is a critical foundation to success.

There will always be some strategic functions that must be performed at the center of government for the benefit of the whole nation.

1. Strategic risk management

- Governments must continuously assess and articulate a strategic understanding of risks, develop national strategy, and set clear expectations about priority activities.

- The national level also plays a critical role in understanding progress and adapting to events.

- National governments can also inspire and engage civic efforts with effective communication strategies and exercises. (For example, Taiwan has civil defense drills to raise population awareness and preparedness.)

2. Border management and resilience

- The federal government plays a unique role in securing and managing the nation’s borders as a core function of national resilience. Effective border management is essential for maintaining national sovereignty, economic stability, and public safety. Unlike other levels of governance, only the federal government has the authority and resources to coordinate national border security strategy, enforce immigration laws, and protect critical infrastructure at ports of entry. This includes

- identifying and managing transnational threats such as organized crime, human trafficking, drug smuggling, and adversary-led infiltration efforts;

- investing in infrastructure and technology;

- coordinating crisis response, including managing large-scale migration surges, health-related border threats, and disruptions to cross-border trade through coordinated federal action; and

- leading intelligence integration and federal-state cooperation by, for example, strengthening information sharing among federal agencies, state governments, and allied nations to enhance border security and crisis preparedness.

3. Resilient infrastructure, supply, and manufacturing capability

- The full picture of the resilience of critical infrastructure (energy grids, supply chains, water systems, digital networks, etc.) can only be brought together at a national level where gaps can be identified and direction set.

- Macro industrial strategy can have major influence on core resilience priorities. For example, incentivizing domestic manufacturing in key areas such as battery or semiconductor production, or energy production and storage, decreases reliance on politically or geographically unstable regions.

4. Political stability and institutional resilience

- Resilience is not just about physical assets; it also depends on the strength of (and trust in) democratic institutions, governance structures, and public trust in leadership.

Case study: Japan’s earthquake program

Japan has a deeply embedded culture of resilience that began with the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923, which left approximately 140,000 people dead. In the aftermath, Japan recognized the necessity of fundamentally reshaping its infrastructure, its national psyche, and its approach to disaster preparedness.

Japan crafted a comprehensive blueprint for earthquake resilience. The Japanese government established “Disaster Prevention Day” on September 1 of each year, commemorating the Great Kanto Earthquake and reinforcing collective memory and preparedness by requiring schools, businesses, and communities to participate in earthquake and tsunami drills. These regular drills are more than just procedures—they serve to ingrain a mindset of readiness into every individual, reinforcing Japan’s communal responsibility in disaster response.

The magnitude 9.0 earthquake of 2011, known globally for its catastrophic tsunami and subsequent Fukushima nuclear plant disaster, was another pivotal moment. Despite Japan’s advanced preparedness, the event exposed critical vulnerabilities. In response, Japan once again adapted by enhancing tsunami early warning systems, increasing the number of emergency shelters, establishing a National Resilience Promotion Headquarters to coordinate resilience-building efforts across government sectors, and implementing the Fundamental Plan for National Resilience, which promotes public-private partnerships to mitigate risks. Japan’s continuous evolution of disaster preparedness strategies, combined with community-wide participation, has created a culture in which resilience is not just practiced but lived.

The role of national resilience: Recommendations for the AANSRI

1. Develop a strategic risk product to prioritize national resilience efforts.

- To support the development of the new US risk register—a public document that outlines the US government’s assessment of risks facing the nation—compare approaches to comprehensive strategic risk products that map, compare, and prioritize different national security risks (both threats and hazards) in a way that informs whole-of-government decision-making.

- Develop practical policy recommendations for how a consolidated national risk framework could drive better choices and more coherent resilience planning across agencies and stakeholders.

2. Embed resilience in national security strategy.

- Investigate the role of resilience in deterrence, exploring whether adversaries are less likely to exploit vulnerabilities in highly resilient societies.

- Determine what a resilient nation looks like and how a government knows that progress is being made. Develop a national resilience index that compares like-minded countries, offering a benchmark for achievement.

- Explore options for implementing national resilience goals (learning from other top-down, cross-cutting policy imperatives such as the Baltic states’ whole-of-society resilience policies.)

3. Enhance government levers to strengthen infrastructure resilience.

- Investigate how the state can better deploy regulatory mechanisms, incentives, and public-private partnerships that could accelerate adaptation in critical infrastructure, rather than relying solely on federal mandates and funding.

- Generate innovative options for transferring resilience responsibilities away from the federal government.

- Explore how legal and policy tools (for example, tax incentives, zoning laws, and procurement strategies) can be used to embed resilience requirements into infrastructure projects.

4. Harness new technologies for national resilience.

- Bring together an advisory team to discuss how AI and emerging technologies can be introduced at a national level to enhance resilience (including by supporting state and local areas) through predictive risk modeling, crisis response automation, and real-time decision support.

5. Building critical skills, supplies, and industry capacity.

- Learn from Ukraine what national-level influence can be exerted now to ensure that the United States can pivot in response to future demands.

- Conduct an analysis of national skills and manufacturing capabilities, identifying gaps that could hinder rapid adaptation to new resilience challenges such as supply chain disruptions, pandemics, or emerging cyber threats.

- Develop recommendations for how governments in free-market economies can build domestic capacity in critical industries.

6. Develop crisis simulation, scenario planning, and crisis anticipation.

- Design practical resilience audit stress tests for governments, like financial stress tests, to evaluate national preparedness across multiple risk domains.

- Investigate how national crisis simulations can be improved and made more accessible and engaging for the public. Determine what role technology and game culture could play in this. Decide what practical recommendations could be made to support governments in ensuring that planning goes beyond singular, expected risks to prepare for cascading and concurrent crises.

- Assess how data-driven modeling and predictive analytics can improve early warning systems and real-time crisis management.

7. Explore mechanisms for better bipartisan cooperation on resilience.

- Conduct a feasibility study looking at how to generate more effective political consensus on long-term resilience. Examine how a new Resilience Commission (comprising members of the executive branch, legislative branch, state and local governments, the private sector, and academia) might work.

8. Contextualize the national role in border and transnational resilience.

- Develop a framework and conduct comparative assessments of border region resilience and state capability levels to map sub-national resilience.

- Analyze how border and non-border regions manage shared pressures, with a focus on improving interstate or interprovincial information sharing in both federal and non-federal systems.

- Examine the evolving role of private-sector actors in deploying border surveillance and detection technologies (e.g., AI, biometrics, and drones), and their implications for governance, ethics, and effectiveness.

International resilience: Rewiring cooperation for a riskier world

No resilient nation is formed in isolation. Although many of the globalized practices on which the free world has come to rely can be adapted to an era of greater self-reliance, US allies and partners are still experiencing globalized risks. In addition to international terrorism and weapons proliferation, cyber threats, pandemics, climate change, and geopolitical instability are all borderless in nature and international resilience has become increasingly critical to any response. While countries might build strong abilities to develop domestically, their ability to withstand crises often depends on global supply chains, multilateral institutions, and strategic alliances.

Global resilience is often the weakest link in the resilience chain. Nations operate with competing interests, sovereignty concerns, and economic rivalries, making it difficult to develop cohesive, international strategies for resilience building. Multilateral organizations—such as the United Nations, NATO, and the G7—play a role in shaping resilience frameworks, yet coordination remains inconsistent and enforcement mechanisms are often weak. Countries such as China and Russia that are seeking to undermine US resilience are often in the room and influencing events. The United States needs to rethink how its allies work together, plan together, and build resilience among democracies.

Much of the decision-making and investment in resilience at an international level is undertaken by the private sector and driven by commercial motivations. Binding the private sector into resilience efforts is a critical challenge facing democratic governments also seeking to enable free-market economies.

Understanding the risks the US faces can also be greatly enhanced by partnership with other nations, whether focused on threats or hazards.

The role of international collaboration in developing resilience

Alliances

Military and economic alliances, such as NATO and the Five Eyes intelligence network, offer shared security frameworks that can enhance domestic resilience through collective defense and intelligence sharing. However, these alliances were primarily designed for traditional security objectives rather than resilience-specific cooperation. Their current engagement with emerging risks such as climate change, pandemics, and cyber threats reflects an ongoing evolution, rather than a foundational mandate. The degree to which resilience coordination is embedded in these partnerships varies, with many focusing on reactive capabilities rather than proactive preparedness. Critical national infrastructure is often owned and operated by private entities that do not usually have a seat at the table in nation-nation conversations.

While multilateral alliances remain critical to building national resilience, recent shifts in US policy emphasize a more bilateral and results-driven approach to security cooperation. Traditional alliances provide valuable frameworks, but they are often slow to adapt, constrained by bureaucratic inefficiencies, and susceptible to diverging national interests. In contrast, direct bilateral partnerships allow for more agile, interest-based cooperation, ensuring that resilience efforts deliver tangible outcomes rather than being diluted by multilateral consensus building.

The challenge is to balance this bilateral model of resilience building with broader alliance structures, ensuring that the United States remains engaged in cooperative security while avoiding overreliance on institutions that might lack enforcement mechanisms or strategic alignment.

Global supply chains and economic interdependence

Supply chain security has emerged as a critical dimension of economic resilience, particularly in relation to strategic resources such as semiconductors, rare earth elements, food supplies, and energy. International trade relationships and global production networks can act as resilience multipliers by providing redundancy and flexibility. At the same time, these networks introduce systemic vulnerabilities, as demonstrated by disruptions stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic, geopolitical tensions, and armed conflict. The same structures that enable diversification can amplify shocks, depending on their concentration risks and governance mechanisms.

Multilateral governance and global crisis response

Global institutions such as the United Nations, World Health Organization, and World Bank play significant roles in coordinating international responses to crises. Their capacity to support resilience at the national level depends on mandates, resourcing, and institutional agility. Mechanisms like emergency funding or technical assistance are useful in supporting less well-equipped member states, but institutional effectiveness is uneven and often constrained by political fragmentation and bureaucratic inertia. In contrast, regional organizations like the European Union and Association of Southeast Asian Nations have demonstrated more targeted resilience-building efforts within their jurisdictions, highlighting the potential of geographically or politically proximate frameworks to drive coordinated action.

Cybersecurity and information resilience