This article is part of a series published by the Atlantic Council’s Africa Center and the GeoStrategy Initiative of the Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security exploring the nexus between US security and economic interests across Africa. The previous edition can be read here.

Fourteen years after the 2011 uprising and NATO-led military intervention that toppled Muammar Gaddafi, Libya remains divided. While the internationally recognized Government of National Unity (GNU) rules the northwest, the Libyan National Army (LNA), led by military leader Khalifa Haftar, controls most of eastern Libya—with both factions backed by competing foreign militaries.

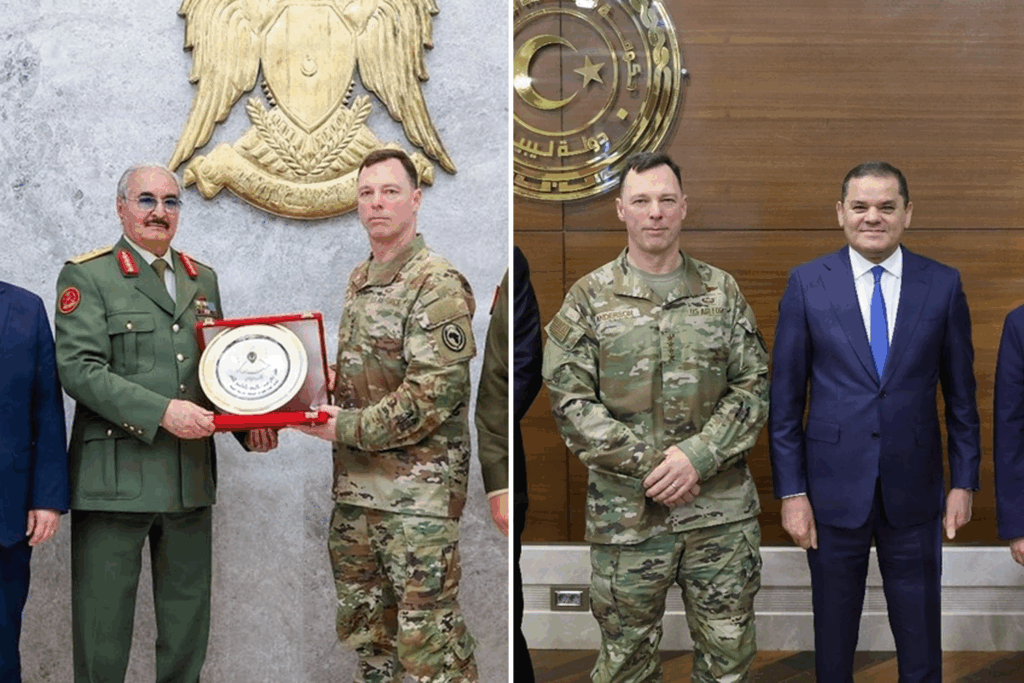

For years, the situation on the ground seemed frozen. Yet two recent developments mark a shift: Oil majors are returning to the country, and the United States is stepping up its military engagement. The visits by the top leadership from US Africa Command (AFRICOM) in October and December last year and the announcement that Libya will join Exercise Flintlock—AFRICOM’s largest annual special operations exercise historically focused on West Africa—signal that the US administration now views Libya’s trajectory as inseparable from broader regional stability.

Against this backdrop, the United States has a narrow—but real—opportunity to reset conditions in Libya by combining carefully calibrated security engagement with strategic investment. Taking this opportunity is urgent, especially as Russia and other foreign powers seek to cement their influence over the southern Mediterranean’s political future.

Libya’s geostrategic significance for energy, Europe, and the Sahel

Libya straddles Europe and Africa. While its coastline faces Italy, its southern expanse feeds directly into the Sahel, where al-Qaeda-aligned groups such as Jama’a Nusrat ul-Islam wa al-Muslimin and Islamic State (IS) affiliates operate. What happens in Libya affects US and European energy security, regional counterterrorism efforts, and global migration flows. Moreover, the country produces between 1.2 and 1.4 million barrels of oil per day and aims to reach two million by 2030. With Western sanctions tightening on Russian energy, Europe increasingly views Libyan crude oil as a pressure-valve alternative.

In November, Shell, Chevron, Eni, TotalEnergies, and Repsol* were all pre-qualified to participate in Tripoli’s first exploration auction in eighteen years. However, instability in southern Libya continues to amplify extremist mobility and arms flows from the Sahel, directly threatening these investments. That risk is further compounded by the expansion of Russia’s Africa Corps—the successor to the paramilitary Wagner Group—in the east and south. Meanwhile, the Central Mediterranean migration route remains a sensitive domestic political issue for Italy. Rome’s Mattei Plan is explicitly built around stabilizing Libya’s energy production and migration management.

Navigating fragmentation and proxy competition to unlock investment

Progress in Libya’s hydrocarbons sector remains contingent on a minimum threshold of stability and predictability in governance, which is still fractured between the Tripoli-based GNU—backed by Turkey and Qatar—and Haftar’s LNA in the east, supported by Russia (via the Africa Corps), Egypt, and the United Arab Emirates.

The signing of a 2019 maritime boundary treaty with the GNU has given Turkey de facto veto power over Libya’s western security sector and offshore zones. Meanwhile, Russia has entrenched itself in eastern Haftar-controlled areas since 2023. Instead of relying on the Wagner Group, however, Moscow has transitioned to formal involvement via the Ministry of Defense. Russia now controls airbases, logistics hubs, and key desert routes into the Sahel, with personnel positioned near critical oil fields and terminals—the same assets the Tripoli government is attempting to license to Western firms.

The result is that Libya has become the Mediterranean’s most active proxy chessboard, with foreign powers positioning themselves to capture future revenues from hydrocarbons and reconstruction. Absent a credible US counterweight, decisions on energy access, migration management, and political transition will be made in Moscow or elsewhere—but not in Washington or Brussels.

A new window for US reengagement

Two developments suggest a modest but meaningful upward trend in US reengagement. First, building on the US Navy ship visit to Libya in April (the first in fifty years), AFRICOM’s deputy commander visited GNU-controlled Tripoli and LNA-held Sirte in October. Inviting Libya to Exercise Flintlock was deliberate signaling: The US government seeks to pull Libya into a broader Western security network—rather than cede the field to other countries with stronger influence, such as Russia. This trajectory continued in early December, when Prime Minister Abdul Hamid Dbeibah met AFRICOM’s commander to expand cooperation on training, equipment, and force professionalization. The GNU’s public request for deeper US support in professionalizing Libya’s security forces marks a notable shift after years of strategic hedging between Washington, Ankara, and Doha.

Second, there has been a surge of activity around Libya’s energy sector. Since 2023, oil output has stabilized, front lines have frozen, and neither the LNA nor the GNU has achieved decisive military or political dominance. This stalemate has created political space for external influence. Energy-sector momentum has been reinforced by high-level diplomatic traffic in both directions. The US special envoy for Africa and Arab Affairs, Massad Boulos, traveled to Tripoli and Benghazi in July, followed by a GNU delegation visit to Washington in August. That trip signaled the GNU’s intent to re-anchor Libya with Western stakeholders and request US assistance in pushing Russia out of eastern military bases to restore unified territorial control.

That momentum was further reinforced by a joint statement on November 26 from the United States, major European partners, Gulf states, Turkey, Egypt, and the United Kingdom. The statement backed a renewed mandate for the United Nations Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL), endorsed a political roadmap by UNSMIL head Hanna Tetteh, and explicitly called for deeper east-west military and economic coordination—a rare moment of alignment among Libya’s external powerbrokers. For the US administration, this sent the strategic signal that Libya’s unification is now within reach. The window of opportunity, however, is closing fast—and another conflict cycle, election breakdown, or foreign miscalculation could shut it indefinitely.

The energy-security nexus: Why investment alone will fail

The return of oil majors represents the most consequential shift in Libya in a decade. But investment without security is unlikely to endure. In March last year, Libya launched its first licensing round for oil exploration in eighteen years, signaling a bid to attract Western technology, capital, and expertise. Shell, BP*, TotalEnergies, and Eni have reopened channels with the National Oil Corporation (NOC)—and ExxonMobil* signed a memorandum of understanding in August for offshore exploration in the Sirte Basin.

Yet these developments do not change the fact that some of Libya’s most valuable reserves remain under Russian influence. Western firms cannot scale operations without predictable access, enforceable contracts, and baseline security guarantees.

An intentional presence to protect investment

To consolidate recent political and economic gains—and protect sizable Western energy investments—the United States should deliberately expand its diplomatic, military, and economic presence in Libya, in close coordination with allies.

The March 2024 announcement that the United States will reopen an embassy in Libya is a critical step toward sustained engagement across military and economic channels. It will also enable closer coordination with key partners—including Italy, Egypt, Turkey, and the UN—whose objectives overlap with US interests.

As the multi-year process to open the embassy inches forward, AFRICOM and its components should pursue near-term, high-impact initiatives. US special operations forces should help build and professionalize vetted Libyan special forces units across both western and eastern factions, units that would pursue shared security interests, no matter the progress toward an eventually possible unification. Additionally, maritime partnerships should be expanded rapidly to strengthen Libyan Navy and Coast Guard capabilities, particularly in interdiction, offshore asset protection, and port security. At the same time, the United States could leverage its convening power to establish a technical deconfliction cell in Sirte, allowing GNU and LNA representatives to coordinate security around oil infrastructure and prevent escalation. Such mechanisms could also support counterterrorism cooperation, including targeting IS remnants and blocking spillover from the Sahel.

Layered US engagement can unlock stability

However, military engagement alone will not be sustainable without economic development. Given the complex legacy of US involvement—from the economically devastating sanctions of the 1980s to the 2011 NATO intervention and the overthrow of the Muammar Gaddafi regime—the United States must work through partners to advance both economic and counterterrorism objectives. The US International Development Finance Corporation and the Export-Import Bank could prioritize export credits for pipelines, gas processing, and power generation, explicitly linking financing to transparency and anti-corruption benchmarks.

US and partner foreign assistance could also support long-overdue reforms at the NOC, including modern contracting practices, environmental standards, and shared revenue frameworks. These efforts should extend beyond governments: Western energy companies involved in Libya should participate in coordinated infrastructure planning, rather than simply launching isolated investments.

Layering diplomatic, military, and economic tools would allow the United States to establish a modest but coherent posture capable of unlocking outsized stabilization effects—and preventing any country that works against US interests from having dominance over Libya’s future. For the United States, Libya offers a proving ground for a new model of engagement—one built on security assistance that enables Western investment instead of substituting for it. AFRICOM’s renewed presence and the surge of Western energy interest create a rare opportunity to reintegrate Libya into a Western orbit. If the United States seeks stability in the Mediterranean, resilience in the Sahel, and credible alternatives to Russian energy, now is the time to make coordinated security and economic investments in Libya.

Rose Lopez Keravuori is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Africa Center, an associate director at Strategia Worldwide, and chair of the board of advisors of GCR Group. She previously served as the director of intelligence at the US Africa Command.

Maureen Farrell is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security and vice president for global partnerships at Valar, a Nairobi-based strategic advisory and risk firm. She previously served as the deputy assistant secretary of defense for African affairs and director for African affairs at the US National Security Council.

Note: Several companies mentioned in this article—Shell, BP, Chevron, Eni, TotalEnergies, Repsol, and ExxonMobil—are donors to the Atlantic Council but not to this article series.

The Africa Center works to promote dynamic geopolitical partnerships with African states and to redirect US and European policy priorities toward strengthening security and bolstering economic growth and prosperity on the continent.

The GeoStrategy Initiative, housed within the Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security, leverages strategy development and long-range foresight to serve as the preeminent thought-leader and convener for policy-relevant analysis and solutions to understand a complex and unpredictable world. Through its work, the initiative strives to revitalize, adapt, and defend a rules-based international system in order to foster peace, prosperity, and freedom for decades to come.

Further reading

Tue, Nov 25, 2025

El Fasher is only the latest wake-up call to the genocide unfolding in Sudan

AfricaSource By Rama Yade

Sudan’s civil war has become one of the world’s deadliest crises—and the massacre in El Fasher exposes a genocide unfolding in plain sight. As regional powers fuel the war, millions face famine, displacement, and systematic violence.

Mon, Nov 24, 2025

In Mozambique, US economic priorities hinge on security investments

AfricaSource By Rose Keravuori, Maureen Farrell

US-backed gas and mining projects could transform Mozambique’s economy, yet persistent terrorist violence threatens progress. Targeted security partnerships offer a path to protect communities and safeguard investments.

Fri, Oct 31, 2025

Mali has not just plunged into crisis. It has been unraveling for years.

AfricaSource By

Mali’s crisis runs deeper than recent coups. Military fragmentation, jihadist expansion, and severed international ties have left the landlocked nation isolated, economically strained, and socially fractured.

Image: In this composite image, US AFRICOM Commander Dagvin Anderson meets with LNA Commander Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar (left) and Prime Minister Abdul Hamid Dbeibah (right). Photos via US AFRICOM/Takisha Miller/DVIDS. The appearance of US Department of Defense (DoW) visual information does not imply or constitute DoW endorsement.