On March 11, the Ministry of Public Health and Hygiene of Côte d’Ivoire confirmed the country’s first case of COVID-19. The individual who tested positive for the virus was a forty-five-year-old Ivorian man who had returned from Italy the week prior and presented himself to public health authorities after developing symptoms. This made Côte d’Ivoire the eighth country in sub-Saharan Africa to have a confirmed case of COVID-19 and came after several suspected cases came back negative after testing between January and March. One of those was the first suspected case of the virus in sub-Saharan Africa, when an Ivorian student returned from China.

Following the confirmed case of COVID-19, health authorities immediately began tracing the contacts that he had prior to testing positive. This led to the individual’s wife testing positive for COVID-19 the following day, bringing the total number of cases to two. Days later, on March 14, authorities announced three additional confirmed cases. All were Ivorian citizens, and two had traveled abroad (to Italy and France) in recent weeks. But the third case was a health worker at a school who had not recently been outside of Côte d’Ivoire, raising fears that community transmissions were already occurring.

Despite the fact that four of the cases at this time were directly linked to travel in Europe, no travel restrictions were put into place. In fact, around half a dozen direct flights from Europe continued to arrive at Abidjan’s Félix-Houphouët-Boigny International Airport daily, each carrying hundreds of passengers. Ivorian authorities also continued to allow passengers arriving from China unimpeded entry into the country (though there are no direct flights to or from Abidjan and China). However, health screening was put into place for all passengers arriving on international flights to the country. The screening checked for symptoms such as fever and a cough, and was similar to those put in place during the Ebola epidemic in 2014.

I experienced those health screening measures when arriving on one of the three Air France flights that landed in Abidjan on March 15. Prior to landing, all passengers on the nearly full flight were given a disembarkation card to register themselves with the Ministry of Public Health and Hygiene, requiring them to describe the length of their intended stay in Côte d’Ivoire and to provide multiple ways that the government could contact them. Immediately after disembarking, all passengers had to apply hand sanitizer prior to going through multiple rounds of health screening that included a detailed examination of travel history, along with having temperatures recorded. Some of those who exhibited symptoms or had travel history to recent hotspots appeared to be taken aside for additional screening. But, after passing through screening, the passengers arriving from France—which at the time had the second-highest number of COVID-19 cases in Europe after Italy—were able to disperse into the most populous city in Côte d’Ivoire.

This occurred as the Ivorian public began to grapple with the impact that community transmissions of COVID-19 could have on the country. At the urging of the government, sanitation measures were taken including placing hand sanitizer at the entrance of many shops, while some restaurants attempted to have a bottle of it at each table. Consequentially, pharmacies began to run out of both hand sanitizer and soap, telling customers to come back the next morning. Some Ivorians began to express worry that there might already be cases of COVID-19 transmitting in-country, refusing to shake hands and attempting other measures of social distancing. Despite these measures, life went on as normal throughout the city. Public transport vehicles such as buses and shared taxis were full, schools and universities continued to operate, and few people wore masks and other forms of protective gear.

Concern about COVID-19 was not felt by all Ivorians, some of whom believed that the pandemic did not pose a threat. A security guard working at a mosque in Abidjan’s Plateau commune insisted on shaking hands, saying, “There is no corona here, look at the sun, it is warm here.” He was referencing an unproven theory that in warm climates COVID-19 is not easily transmitted as it is killed by the heat. Others said that the only cases in Côte d’Ivoire were brought in by people from outside of the country, and therefore it was not of concern to Ivorians who do not travel regularly. Further, some demonstrated a lack of general knowledge about the pandemic. For instance, a taxi driver in Abidjan by the name of Simo was not familiar with the terms COVID-19 or coronavirus but was simply aware that there was a “disease from China” that was beginning to spread.

On the evening of March 16, Ivorian President Alassane Ouattara announced that he had convened a meeting of the National Security Council to discuss the country’s response to the pandemic, indicating the seriousness of the government’s approach. That meeting led to the announcement that entry would be denied to any foreigner attempting to enter Côte d’Ivoire from a country with over one hundred confirmed cases of COVID-19, along with the “reinforcement” of health screening at ports of entry. Most notable, however, were the social distancing measures imposed within Côte d’Ivoire, including the suspension of all schools for thirty days and the closure of all night clubs and cinemas for fifteen days, along with banning gatherings of more than fifty people for two weeks.

The following day little appeared to change in Abidjan. Two of the city’s largest malls—Abidjan Mall and Playce Shopping Mall—were full of customers, although a notable number of them wore face masks and gloves. In the Carrefour market at Playce Mall, people appeared to be partaking in panic-buying, purchasing large quantities of non-perishable goods such as beans, rice, and pasta. Yet, this behavior appeared to be limited to those of a middle or upper socioeconomic standing. At the main outdoor market in the relatively working-class commune of Koumassi, few exhibited any concerns about the pandemic. Children who were out of school assisted their parents in crowded market stalls, people gathered around in close quarters in drinking spots, and people ate communal dishes. Some night clubs also remained open but were shut down by the police and gendarmerie who were doing patrols.

When asked about the potential of having to close down market stalls during a potential future lockdown, many said that would not be possible. A woman who sells dried fish in the market said, “I cannot stay home from work. If I do not sell my fish, I do not have money to feed my children and then we will all die.” Around 30 percent of Côte d’Ivoire’s population lives in extreme poverty and survives off of income made each day, and even more of the population works in the informal economy. For this segment of the country’s population, the notion of not being able to work every day is not just difficult to comprehend—it would lead to unimaginable suffering. In some countries, governments have attempted to provide assistance to workers in the informal economy impacted by the pandemic, but few believe that the Ivorian government has such capacity. Others believe the political elite simply is not willing to make sacrifices for Ivorians outside of their patronage networks, an indicator of the polarization that still exists in the country after the civil war in 2011 that killed thousands.

The number of confirmed cases of COVID-19 continued to increase in Côte d’Ivoire, rising to nine on March 19. The government responded by announcing the cancellation of all international flights arriving at Abidjan Airport, along with the closure of land and maritime borders. Quarantines were also mandated for Ivorians returning to the country. As confirmed cases grew, so did the concern of Ivorian citizens. Serge, who makes a living driving a taxi between the resort town of Assinie-Mafia and Abidjan, wore a mask and was hesitant to shake hands. He would have preferred not to be working at the time, saying “my wife told me not to leave our home, but I have no choice: if I do not do this we will not eat.” He went on to express deep worry about the impact COVID-19 could have on the country, especially outside of major cities: “In many towns, the hospitals have no more than five beds, and sometimes not even a single doctor. If this thing arrives here, we are finished.” Even though Côte d’Ivoire was listed by the World Health Organization (WHO) as one of eight countries in Africa prepared to respond to an outbreak of COVID-19, it is clear that confidence is not shared by all Ivorians.

On March 20, just over a week after the country’s first confirmed case, Ivorian authorities announced five additional cases, bringing the total number of infections to fourteen. The following day it rose to seventeen. The government responded by limiting the quantity of people who can utilize public transport and urged all Ivorians to take sanitation measures seriously. Even with these measures, confirmed cases continued to rise, reaching eighty on the March 25. As cases climbed, the government put in place strict measures. All restaurants and bars were closed, a national curfew from nine in the evening until five the next morning was put into place, and unauthorized travel between cities was banned. However, life during the day largely remains normal with people commuting to work and markets being packed, allowing plenty of opportunities for community transmission.

For the most part, the measures are being enforced with authorities arresting those who violate it. However, it appears that the measures do not equally apply to all. Even though a period of quarantine is required for all Ivorians entering the country, there are reports of individuals close to the government evading the measures. Similarly, public anger emerged about Chinese nationals being able to enter the country after the government banned foreigners from countries with over 100 confirmed cases. Should the elite of the country be exempted from the prevention measures, the consequences could be drastic. Other African states such as Cameroon and Burkina Faso have seen government officials become infected and transmit cases to others. Already, the Ivorian prime minister and ruling party presidential candidate in this year’s elections went into self-isolation after coming in contact with someone who had tested positive. Although he later tested negative, the potential consequences of COVID-19 impacting candidates in an election that many believe could lead to a return to conflict are drastic.

It is clear that Côte d’Ivoire has taken measures to combat the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic within its borders, both by imposing travel restrictions and limiting domestic movement. Whether those actions came too late, and whether the Ivorian population will comply with the required lockdown, remains to be seen. If they do not, coronavirus is likely to overwhelm not only the country’s health systems, but the economics, politics, and stability of the country.

Maxwell Bone is a former intern with the Atlantic Council’s Africa Center. Follow him on Twitter @maxbone55.

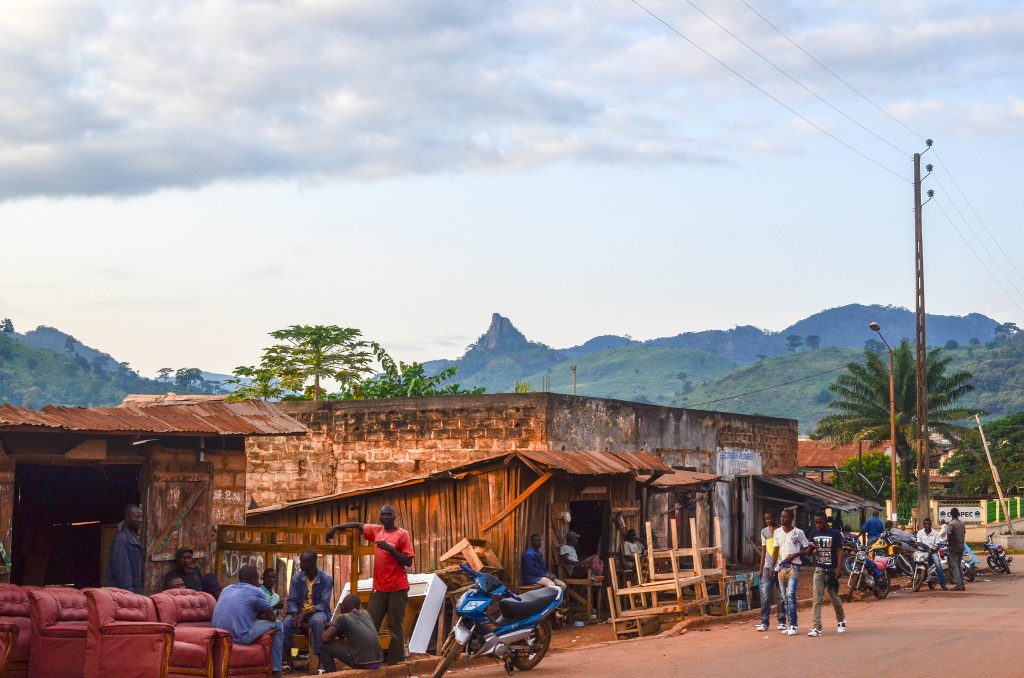

Image: People gather to socialize near Man, Côte d'Ivoire. (Flickr/jbdodane)