African elections in the time of coronavirus

African elections slated for 2020 are already being affected by COVID-19, with the potential for delays and disruptions to have significant impact on election credibility, political trust, and adherence to term limits across the continent.

In a year of high-profile elections across the continent, logistical preparations are already ongoing and were meant to be ratcheting up in places like Ghana, which is slated for presidential polls in December, and Ethiopia, where parliamentary polls are set for August. Both countries still need to prepare the voter roll, but bans on public gatherings have flipped electoral timelines on their head. Ghana’s Electoral Commission has announced an indefinite delay of the voter registration exercise, though it promises to resume as soon as possible. With elections approaching sooner and facing a larger population, Ethiopia’s logistical dilemma is even greater. Registration was intended for April with campaigning to begin in May, both well within the window in which COVID-19 looms large.

While election delays would likely prompt bigger headlines than truncated registration periods, the importance of these pre-election logistics cannot be overlooked. The international community should be especially vigilant under these circumstances and be willing to speak up sooner rather than later if countries pursue untenable schedules that imperil the underlying credibility of the polls.

Unfortunately, decisions to delay or revise election programming are bound to be politicized. Opposition groups across the continent are already using governments’ virus response as a means to criticize ruling parties. The General Secretary of Ghana’s main opposition party, for example, has claimed that the ban on public gatherings is a conspiracy to rig the election. This comes as many elections on the continent already face significant trust deficits and a status quo of losing parties crying foul (based on evidence of irregularities or otherwise). In 2019, all nine of the presidential contests on the continent were marred by alleged irregularities, with losing parties taking the results to court in all but Senegal and South Africa. Coronavirus disruptions and accompanying disputes risk further cementing this sub-optimal status quo.

An element of African elections that had been improving as of late is adherence to term limits. This past year, Mauritania’s leader stepped down abiding by term limits, and looking ahead, Presidents Ouattara of Côte d’Ivoire and Nkurunziza of Burundi have agreed not to run for additional terms in 2020. Burundi goes to the polls in May, while Côte d’Ivoire will do so in October. While there have been no definitive signs of these politicians altering course at the time of writing, the potential for coronavirus-related states of emergency to be abused cannot be ignored. Further scrutiny should be placed on Burundi, where even if Nkurunziza keeps his promise, his ruling party may be incentivized to skew the playing field toward their new candidate, who analysts say may be the underdog in a free election. The polls are unlikely to be fully credible, and certainly will not be sufficiently observed, but careful attention should be placed on further attempts to restrict campaigning, which would disproportionately hurt the opposition.

Of particular note is Guinea’s decision to go ahead with elections on Sunday, March 22, which included parliamentary polls and a boycotted rubber-stamp referendum on a new constitution that will pave the way for President Alpha Condé to stay in power. With two confirmed cases, and neighboring countries having already limited public gatherings, Guinea’s decision to go ahead has understandably been met by scrutiny. It is hard not to read the situation as an example of political imperatives trumping health directives, and the election’s fallout will advise others as a test case of election administration under coronavirus.

Guinea’s health situation should be watched carefully in the coming days, with the potential for political and social tensions to rise if cases balloon following a day of crowded polling stations and intra-country travel associated with administering the election. Such a scenario would reflect badly on President Condé, whose politics-as-usual post on election day (below) is in stark contrast to the Twitter content of other African leaders, who have taken to the platform to advocate social distancing and hygiene practices.

Lastly, while presidential contests will be the most publicized, it is worth bearing in mind that parliamentary and local government elections could also be disrupted in places like Gabon (late 2020), Mali (May), Namibia (November), Senegal (late 2020), and Somalia (December). In many places, the average citizen deals more with these types of officials in day-to-day affairs and service provision, meaning that disruptions could be impactful.

With these themes in mind, the Africa Center will continue to follow elections around the continent this year in the time of coronavirus. Be sure to follow our page for updates as they emerge.

Luke Tyburski is a project assistant with the Atlantic Council’s Africa Center.

Questions? Tweet them to our experts @ACAfricaCenter.

For more content, go to our Coronavirus: Africa page.

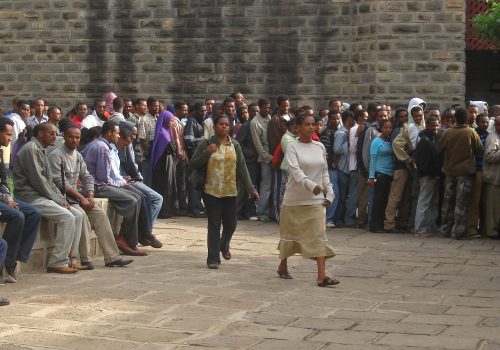

Image: Election administration in Ghana, which is slated to go back to the polls in December 2020 (Flickr/Erik Cleves Kristensen)