Data remains a weak spot for African elections, but Ghana can lead the way

Despite the near-universal presence of observers, many African elections continue to be plagued by persistent allegations of fraud. In 2019, for example, claims of irregularities were raised in all nine presidential contests held in sub-Saharan Africa, with only Senegal and South Africa avoiding official court challenges. Paired with generally cautious observer reports, the prevalence of contested polls leaves an unsatisfying lack of clarity and confidence for many African voters. In this context, data transparency has the potential to add value, reducing spurious claims while supporting litigation efforts. Unfortunately, the international community, and large segments of domestic civil society, has yet to show an appetite for funding in Africa the types of substantive data collection and analysis that is considered essential to elections in the United States and Europe.

Despite donor reluctance to fund data collection, the scale and availability of African election data has never been better. For example, election commissions in Malawi and Mauritania released polling station-level results for the first time in 2019, while domestic and international observers regularly collect thousands of raw data points from observer cohorts numbering at times in the tens of thousands. The problem is that while international missions do aggregate these data into topline statistics and general reports, they do not provide the public with access to the granular data. Domestic election monitoring operations are usually even more expansive than international ones, but their findings are even more likely to go unpublished or underpublicized.

Ghana, with elections slated for December 7, may be the most robust environment for domestic election monitoring on the continent, with more than 12,000 observers active during the last election cycle in 2016. But fieldwork I conducted in January 2020 confirmed that most stakeholders still find that data is a “weak spot.” This is not to say that peace and credibility are in doubt in Ghana’s election, but by better leveraging existing data resources, Ghana has an opportunity to champion transparency and set an example for regional peers.

Two weeks of stakeholder interviews conducted in Accra, Kumasi, and Tamale in January 2020 revealed the following key takeaways and specific recommendations to enhance future election cycles, with applicability well beyond Ghana.

Despite ample supply, data is being left on the table

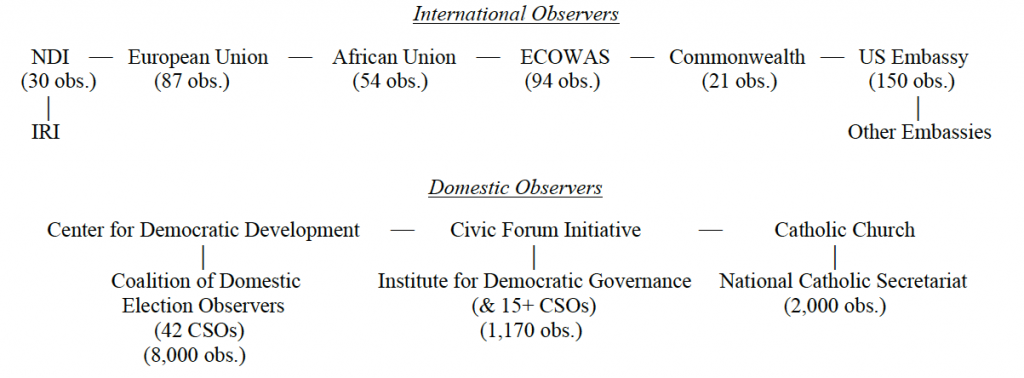

First, the supply of data is not wanting. Ghana’s civil society and election ecosystem is formidable, with actors in 2016 including five international election observation missions (EOMs), three major domestic observer coalitions, two election situation rooms, and countless active media and civil society organizations (CSOs)—see figure below. These groups accounted for more than 12,000 observers and tens of thousands of data points, which if pooled could paint a detailed picture of election day at over a third of all polling stations.

Yet, elements of this data are underutilized or lost in aggregation. Not every observer agency even published a report or digitized their data in 2016, with some citing a lack of donor funding and interest. While election observation may have non-reporting purposes, such as the deterrence of fraud or building voter confidence, the decision not to leverage data that has already been paid for and collected is inefficient. Stakeholders seem to agree, as the most common comment from field interviews was that data remains a “weak point” or “work in progress.” The election commission was also not immune to data shortfalls, failing to fulfill a promise to release polling station-level results.

Demand exists for granular data products

The reality is that demand exists as well, and for more granular products. In expressing interest in better data access, civil society leaders outside of the capital consistently noted that they struggle to access even standard government data, and community radio representatives relayed that it can take weeks to ascertain relatively basic local election results and turnout figures, which are valuable to their work. Thus, while observer reports release national or regional statistics, more localized figures are what could reasonably inform these stakeholders’ activities, enhancing grassroots efforts that are critical to effective governance.

Capacity building will need to be built in

Despite a near-universal desire to better incorporate data into their work, respondents voiced an important caveat that any new program would have to come with capacity building or sensitization. Data products would need to be simple, accompanied by guides on how to interpret them, and disseminated through careful campaigns meant to explain their value to the intended recipients. This might be in the form of trainings for journalists, civil society bosses, or the public at large.

Constraints associated with the donor environment exist

Another takeaway is that donors will have to play a role. Collaboration and data sharing come into conflict, at times, with organizational imperatives: namely, programming and funding. Ghana’s robust civil society space means it is crowded, too, and to compete, organizations have to set themselves apart, while often molding themselves to the desires of external proposals. In this environment, pro bono cooperation becomes a secondary concern at best. The easiest way to resolve this is for donors to explicitly incentivize data usage and sharing, with recommendations on how to do so expressed below.

Local models can be built upon and formalized

None of these reflections are meant to undermine the already outstanding efforts of Ghanaian civil society. To list a few examples, the Coalition of Domestic Election Observers (CODEO) conducted an 8,000-member EOM in 2016 with far more advanced methodology than any international peer; STAR-Ghana, a civil society umbrella group, builds monitoring and evaluation, communications assistance, and lessons learned sessions into its grants process; collaboration between groups already exists even if not always formalized; and an expanding set of actors are recognizing the need to integrate data into their operations. The puzzle is how to ensure that these positive data practices are maximized and routinized amongst the broader ecosystem in ways that can be replicated, both in future election cycles and in other African environments, including those lacking such a developed civil society apparatus.

Building off the takeaways above, the below recommendations outline specific actions that the major stakeholders should consider to better leverage data in African elections.

Donors

Earmark a percentage of program funding for data collection and storage. The average European Union (EU) EOM costs 3.5 million euros, and the US Embassy spent upwards of $5.7 million in 2016 to support Ghana’s election. The reality is that just a couple of percent of this would be all it would take to elevate data collection and reporting. For example, Ghanaian data clerks could be easily trained to input observer reports using applications like CSPro. Further considerations would be hiring several data managers to assist across grantees, and for the construction of a centralized data portal. But realistically, significant progress countrywide could be achieved in the range of several hundred thousand dollars.

Put collaboration explicitly into grants. Stakeholders are open to collaboration and express demand for data products. But many are unlikely to take the effort to process, clean, and share their data with others without an incentive. They may also need a push to formalize cooperation channels with other Ghanaian CSOs. Donors should demand this in their calls for proposals, and could do so by asking for more than one grantee on a project or asking grantees to specify partners or sub-grantees.

Seek grantees earlier in the election cycle and prioritize local input. Programming would ideally be set more than a year out from the election, in contrast to just several months. Early calls for proposals should give CSOs an opportunity to bring their unique ideas and concerns to the donors, at the very least informing the eventual programming, even if more donor-driven in the end.

Emphasize communications and messaging. To a certain extent, the utility of research and reporting is a function of its viewership. Donors should allocate public relations/communications assistance to grantees, and there is no excuse for reports going unpublished or buried on sites with little web traffic. Donors should work to ensure that the reports and lessons learned are circulated to in-country stakeholders as well as relevant external policymakers.

International EOMs

Assess value added compared to other international missions and the broader domestic response. Ghana did not need five international observation missions in 2016, especially with several not submitting public reports and understanding that domestic efforts were orders of magnitude more expansive. When the US Agency for International Development, for example, is deciding whether to fund an EOM or support a competent domestic observer group, it may be best to throw everything at the domestic response. And returning to the issue of messaging, this should include a marketing campaign to ensure DC policymakers are reading more than just an EU report, especially if Ghanaian data and findings are more useful or prescriptive.

Be more active in the dialogue before and after the election. If an EOM is chosen as the most useful instrument, it should be fully leveraged. Even as honest brokers, observers can inject more analysis than is currently done, or at least curate others’ findings. For reference, in Malawi’s disputed election, the EU EOM went silent before the results were even announced, despite contestation that extended more than half a year. Observers should not wait until final reports six months down the line to add value. Even just tweeting out CSO reports, linking to available data, or convening public conversations could be incredibly useful, though a stark contrast to what is normally pursued.

Civil Society

Create a centralized data portal. This would include relevant government, civil society, and observer data organized and available for ease of consumption. The pooling of raw observer data would be a massive breakthrough for transparency and research, though even just putting observer reports and statements in one place would be a valuable start, as some from 2016 proved difficult to find or had to be retrieved from internet archives. This was the central recommendation that came of my fieldwork, and one that received broad approval from civil society interlocutors.

Distribute standard reports aimed at the constituency level. Ideally tied to the centralized data portal, these one-to-two-page reports aimed at the constituency level would be disseminated to relevant local stakeholders. These could ostensibly include vote and turnout trends from prior elections, key incidents reported in the last election cycle, and any notable irregularities. These could provide a localized baseline for stakeholders to integrate into strategic planning, use to assess against once new data comes in, to prepare observers for their specific deployments, and for media stations to provide accurate localized coverage.

Government

Embrace transparency. The election commission should be called upon to publish polling station-level results, as was promised in 2016. The Open Election Data Initiative outlines that this should occur not only in a timely fashion, but also in an easily downloadable format and in a permanent capacity, not to be taken down at a later date.

Conclusion

In Africa, Ghana is often considered a democratic role model, and in many ways this contention is true. Nowhere else can you find such a robust civil society and observer ecosystem, yet even Ghana could substantially benefit from better leveraging existing data resources. Notably, demand for such data resources exists among stakeholders, and the silver lining is that workable solutions are neither excessively costly nor complicated, especially in such a developed civil society environment. Donor emphasis on making progress on data usage and transparency in places like Ghana first might thus be an efficient way to set a positive example and then move toward standardization elsewhere. Streamlining both the donor process and the domestic observer response, the result will ideally be a set of more intentional, impactful programs that are able to iteratively improve over time.

Luke Tyburski is the assistant director of the Atlantic Council’s Africa Center. He is grateful to the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies for supporting the fieldwork that contributed to this analysis.

Image: The BBC's James Afedo checks the results at the international press center in Accra during Ghana's 2008 election. (Flickr/BBC World Service/Peter Lewenstein)