The African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) of 2000 marked an important shift in US-Africa policy, and more broadly US development policy, moving the commercial relationship between US and African markets from aid to trade. While the duty/quota-free access afforded by AGOA is a strength, the policy has largely underperformed in substantially increasing diversified African exports and has done little to stimulate American investments in Africa. The last decade saw the launch of Power Africa and Prosper Africa at the US Agency for International Development (USAID), along with the new US International Development Finance Corporation (DFC), in an attempt to stimulate an investment response. However, they have yet to generate significant investor interest in African opportunities, as US-Africa trade continues to fall or plateau. To remain competitive in many of the world’s fastest growing countries, the United States needs to innovate in the ways it is seeking to support investment into African markets. Just as tech innovation requires experimentation, US commercial policy in African markets needs to embrace and operationalize experimentation.

With African markets younger, more connected, and better integrated than ever before, the US commercial approach to the continent needs revamping. Currently half of Africa’s population is already connected to a smartphone, and in less than ten years, Africa will be home to seventeen cities with over five million inhabitants. Despite COVID-19, the International Monetary Fund estimates a return to 3.2 percent growth in African markets in 2021, matching 2019 levels, and rising to 3.9 percent in 2022. This economic resilience, coupled with positive demographic trends, positions African countries as ideal markets for US capital in search of diversification, yield, and higher returns. However, actively mobilizing investment, particularly from small to medium-sized businesses and less traditional asset classes like institutional investors and venture capital, has not been in the DNA of USAID or the newly operational DFC. Creative and collaborative thinking will be necessary to determine what policies will work in this new era that ultimately benefit the US and African economies.

More commonly seen in technology and research and development (R&D) organizations, rapid, iterative experimentation with a willingness to fail often leads to better solutions. Yet this philosophy is not commonly implemented in the formation or execution of US commercial or development policy. To increase the effectiveness of large efforts aimed at mobilizing US investment in African markets, such as Prosper Africa and its forthcoming Proper Africa Trade and Investment (PATI) initiative, a team should be tasked with small-scale policy experimentation so as to determine the most effective ways to stimulate investment. This new team could either be housed in the Department of Commerce or an expanded Small Business Administration’s (SBA) Office of International Trade, given their domestic reach and respective mandates to enhance the competitiveness of US businesses globally.

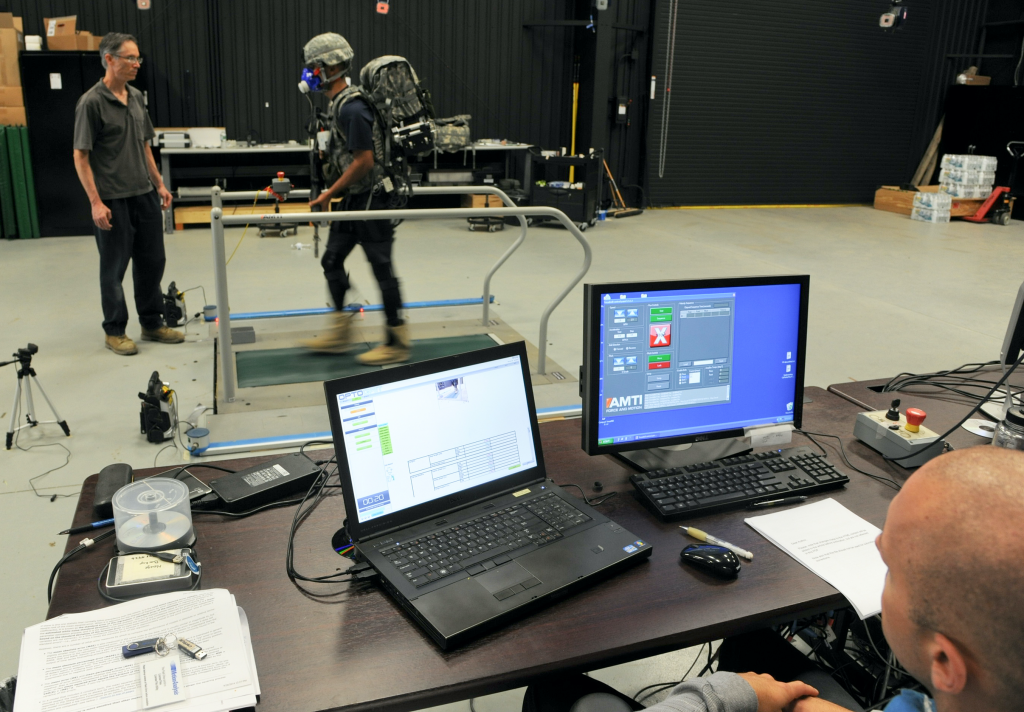

Albeit sizably different in scope and resources, the organizational model of the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), responsible for the development of emerging technologies for the US military, could be an innovative model for the team as the undergirding principles are not defense-specific. According to a former director, DARPA has three mutually reinforcing elements: ambitious goals, temporary project teams, and independence. Substantially increasing two-way trade and investment between the United States and Africa is an ambitious goal, and much like problems DARPA tackles, likely is not going to happen without a catalyst. Temporary project teams are a critical aspect of a successful DARPA project. The limited time frame attracts high-caliber talent that may be willing to leave the private sector for two years but not decades. Taking one small aspect of US-Africa commercial policy, say how to expand partnerships between Hollywood and Nigeria’s Nollywood, could benefit from a small team dedicated to the challenge for two years. Lastly, the effort should have independence. The team needs to be empowered to not only pick the projects it works on, avoiding political and agency priorities, but also have the financial freedom to fail.

A recent project between Prosper Africa and the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) looked to uncover the barriers US companies face in African markets by hosting virtual roundtables in three US cities. Companies shared a myriad of reasons they are hesitant to invest—from the lack of consistent US government support to the issues around data policy in some African countries. This project served as a one-off experiment in matching sector interests to US cities. But it should not be a one-off. What is needed now is a systematic learning process and an ability to test potential solutions, working directly with experts in the private sector. And most importantly an acknowledgement up front that US policy makers and their traditional partners do not have all the answers, but rather a willingness to experiment and to let some endeavors fail.

Given the size and breadth of the American economy, mobilizing US investment into African markets will require experimentation. As a starting point, this new team could focus on experiments in three main areas: messaging, education, and structure. First up, policy makers need a better understanding of how to effectively present African investment opportunities to US investors. Despite years of economic and governance progress in African nations, old stereotypes remain, and US investment is stagnant. By holding focus groups and leveraging innovative public relations and marketing firms, this team could experiment with new messaging tactics to learn what works and what doesn’t. Beyond messaging, effectively educating different types of investors from venture capitalists to pension fund trustees requires some experimentation. This includes everything from determining who in these organizations are the correct targets for education to understanding which up-to-date, actionable data is needed. And finally, experimenting with structure. While the DFC already has experience when it comes to structuring deals to entice private sector players and USAID has been building blended finance expertise, further experimentation with deal structure could focus on how to incentivize US corporate investors or others that traditionally have not engaged with US government agencies.

Ultimately, as US-Africa policy evolves so too must the approaches taken, including those around generating and crafting policy and future programs. Tried and true models like DARPA can serve as inspiration for a new way of thinking about development policy—one that is experimental, agile, and ultimately takes investors’ needs into greater account. With the opportunities in African markets growing and evolving year-over-year, now is the time to experiment with how to better mobilize US investors to ensure American companies remain active and competitive in the decades to come.

Aubrey Hruby is a senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Africa Center. She is also co-founder of Insider and the Africa Expert Network. Follow her on Twitter @AubreyHruby.

Further reading

Image: US Army researchers evaluating prototype devices developed for the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) at the Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland in 2014. (Flickr/U.S. Army CCDC)