Belarus looms large on the US foreign policy agenda for 2021. Senators now have an opportunity to set the stage for a more assertive role in support of the country’s pro-democracy movement by passing the Belarus Democracy, Human Rights and Sovereignty Act of 2020.

This Act, which has already received bipartisan backing in the House of Representatives, would send a powerful signal of support to the Belarusian people, while also indicating to dictator Alyaksandr Lukashenka and his Kremlin backers that the United States remains very much engaged in the region despite the current transition underway at the White House.

The US focus on Belarus has intensified during the second half of 2020 following the outbreak of nationwide pro-democracy protests in the wake of a flawed August 9 presidential election. In mid-December, the Senate signaled its deep concern for the situation in the country by voting to approve the appointment of a new US ambassador to Belarus after a break of more than a decade. Julie Fisher, a respected career diplomat who has previously served as the charge d’affaires at the American Embassy in Moscow as well as deputy assistant secretary for Western Europe, while now become the first US ambassador in Minsk since 2008.

Ambassador Fisher will take up her posting in Belarus with the country in the midst of an uprising that has already taken on historic proportions and been widely hailed as a national awakening. The spark that lit the fire was a nakedly falsified presidential vote orchestrated by a dictator who has held office since 1994. Indeed, many view the current pro-democracy movement in Belarus as a continuation of the post-Soviet transition process that began in 1991, only to be interrupted by Lukashenka’s stultifying 26-year reign.

The Belarusian demonstrators have shown impeccable resilience, perseverance, and discipline in continuing to peacefully demonstrate for over four months despite being subjected to brutal repression from the security services. With all of the original opposition leaders either forced into exile or imprisoned, protests have been coordinated digitally via Telegram channels and social media. From the very beginning, the movement has benefited from an entrepreneurial spirit of innovation and creativity that has allowed protesters to maintain visibility despite the severity of the official response.

While reliable data on public opinion in Belarus is unavailable, there can be little doubt that the protests enjoy overwhelming support among the population. A significant portion of the country’s 9.5 million citizens has participated directly in protest rallies, despite the obvious risks involved in doing so. At the height of the public protests in August and September, weekly rallies in Minsk regularly drew crowds numbering in the hundreds of thousands, while events held in towns and cities across the country also attracted unprecedented numbers.

Despite the scale of the protests, Lukashenka has refused to engage with the opposition and has rejected calls to step down or initiate a new round of free and fair elections. Instead, he has remained defiant and implausibly dismissed the popular uprising as the work of foreign intelligence agencies in league with a fifth column of traitors and social misfits.

With public support for the regime in short supply, the only real evidence of any lingering domestic backing for Lukashenka has come from the Belarusian security services, which have largely remained loyal to the dictator and enabled him to wage an increasingly violent crackdown. A number of protesters have been killed since August. There have also been widespead accounts of torture and human rights abuses from the tens of thousands of Belarusian detainees.

While the loyalty of the security apparatus has been crucial, Lukashenka’s single most important backer has been Vladimir Putin. On a personal level, there is little love lost between Putin and the Belarusian dictator. However, Moscow has no interest in allowing a successful pro-democracy uprising to take place on its own doorstep.

When the protests first erupted in August, the Kremlin responded rapidly. Moscow extended crucial economic and security assistance to prop up the Lukashenka regime, and also dispatched several planeloads of media specialists to coordinate pro-regime propaganda on Belarus state television. Putin was so concerned over the prospect of a possible democratic breakthrough that he publicly pledged to send Russian security forces into Belarus if the situation continued to deteriorate.

Russia’s approach to Belarus reflects Moscow’s deep-seated anxieties over democratic contagion. The collapse of the Soviet Union remains the formative political experience of Putin’s inner circle. Any manifestations of people power inevitably bring back painful memories of the rapid disintegration of Soviet power throughout Eastern Europe in the last 1980s and the extinction of the USSR itself in 1991.

Fears of a new democratic wave continue to haunt the Kremlin. Putin’s current adversarial stance towards the democratic world was cemented by Ukraine’s pro-democracy Orange Revolution in 2004, which was seen in Moscow as a betrayal by Russia’s Western partners. This explains why the Kremlin chose to intervene in Ukraine militarily ten years later following the country’s subsequent Euromaidan Revolution. Similar considerations have determined the Russian response to events in Belarus.

Eurasia Center events

There are signs that Moscow would prefer to usher the unpopular Lukashenka out of office and oversee the installation of a pro-Russian successor. However, with the US presidential inauguration a month away, the Kremlin has a diminishing window of opportunity to implement a managed transition process of its own choosing. Moscow has a clear interest in sorting the situation out to its advantage during the final weeks of the Trump presidency. Putin has made a number of recent statements advocating a national dialogue in Belarus, but Russia is unlikely to risk anything that could be construed as a victory for grassroots democracy.

International pressure on Lukashenka continues to gradually mount. In mid-December, the European Union imposed the latest in a series of targeted sanctions against members of the Lukashenka government and security forces. America now has an opportunity to underline its own stance towards Minsk.

The Belarus Democracy, Human Rights and Sovereignty Act seeks to increase the cost of human rights abuses while bolstering the pro-democracy movement in Belarus. Provisions include an expansion of economic and visa sanctions against Belarusian and Russian officials implicated in the crackdown.

The Act also calls for new elections and the release of all political prisoners. If adopted, it will enable US support for Belarusian civil society, a free press, and the country’s IT industry. Crucially, it also unequivocally states that it is the policy of the United States “not to recognize any incorporation of Belarus into a ‘Union State’ with Russia.” Passing this legislation and also inviting Belarusian opposition leader Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya to attend the January inauguration of the next president of the United States would send a tremendous and unmistakable message of support to the people of Belarus.

Vladislav Davidzon is a nonresident fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Eurasia Center.

Further reading

The views expressed in UkraineAlert are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Atlantic Council, its staff, or its supporters.

The Eurasia Center’s mission is to enhance transatlantic cooperation in promoting stability, democratic values and prosperity in Eurasia, from Eastern Europe and Turkey in the West to the Caucasus, Russia and Central Asia in the East.

Follow us on social media

and support our work

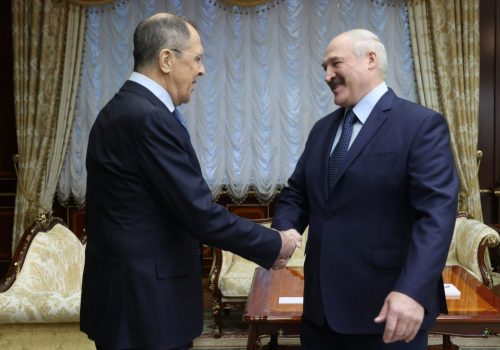

Image: An unprecedented pro-democracy protest movement has been underway in Belarus since August 2020 calling for an end to the 26-year reign of Kremlin-backed dictator Alyaksandr Lukashenka. (Tut.By via REUTERS)