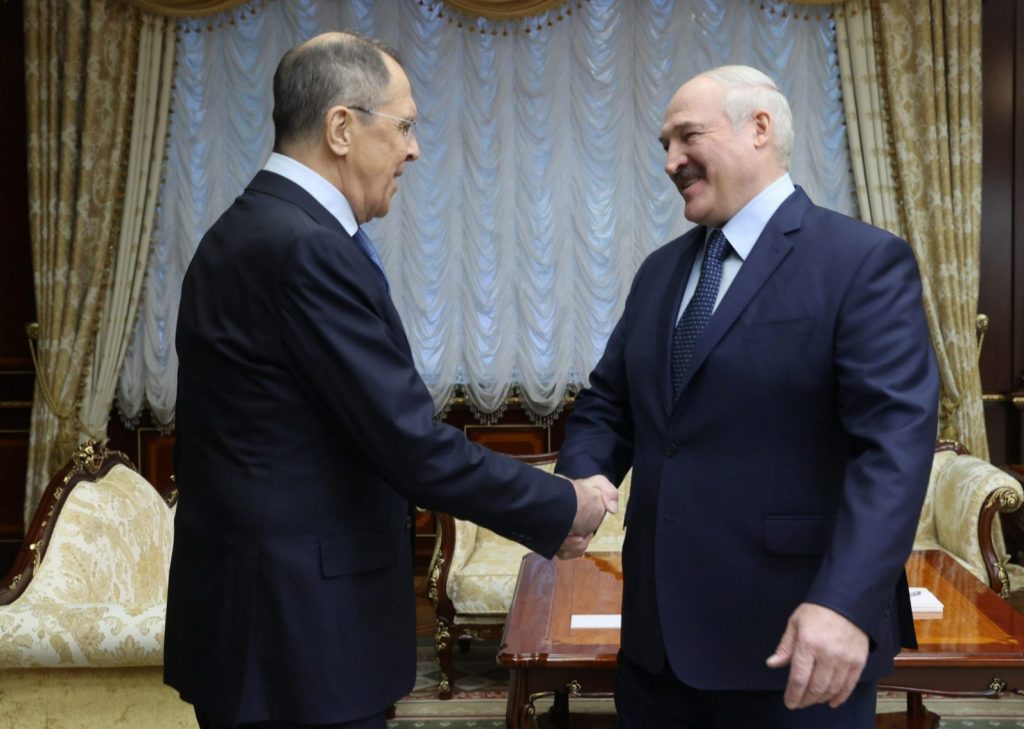

Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov arrived in Minsk on November 26 amid much pomp and ceremony for a face-to-face meeting with embattled Belarus dictator Alyaksandr Lukashenka. Moscow is one of Lukashenka’s few remaining geopolitical allies but this was not to be a friendly visit. Indeed, Lavrov appears to have flown to Belarus with the express intent of pushing for a managed transition of the country’s leadership.

Publicly, at least, Lavrov offered a soothing confirmation of Russia’s continued support. He also took the opportunity to somewhat cynically accuse the West of meddling in Belarus’s internal affairs. However, Lavrov’s main message was aimed not at Warsaw, Washington DC, or Vilnius, but at Lukashenka himself. During a very tense televised meeting, Lavrov proceeded to lecture the Minsk strongman in a manner that underlined the vastly unequal power dynamic between the two men.

Reading between the lines, it seems that Lavrov’s aim was to lay out a political ultimatum on behalf of an increasingly impatient Kremlin. The exact terms of this ultimatum still remain undisclosed, but they appear to be based on a deal struck during Lukashenka’s September 2020 meeting with Russian President Vladimir Putin in Russian Black Sea resort city Sochi.

Lavrov reminded Lukashenka that the Russian side is now waiting for him to implement the agreements reached in Sochi. He specifically referenced reform of the Belarusian Constitution, a process that would curb the power of the Belarusian presidency. These constitutional changes are widely seen as an opportunity for Russia to engineer a Kremlin-friendly transition of power in Minsk. It is a transition that Moscow has desired for a very long time.

The political theater of Lavrov’s visit created the distinct impression that Russia recognizes the fundamental weakness of Lukashenka’s present position and does not plan on propping him up indefinitely. Instead, Moscow is attempting to find a solution that will calm the current crisis without threatening Russia’s geopolitical interests in the country. Moscow well understands the adage that “things must change to stay the same.”

When pro-democracy protests first broke out in Belarus at the start of August 2020 following a flawed presidential election, Russia intervened promptly to prevent the regime from collapse. The Kremlin provided Lukashenka with teams of television propagandists as well as a series of financial lifelines, while Putin also publicly declared his readiness to deploy security forces if the situation escalated further.

This Russian intervention in Belarus was not intended as a show of support for Lukashenka himself. Instead, it was driven by a deep-seated Russian fear of pro-democracy uprisings in the post-Soviet neighborhood, what political scientists refer to as “democratic contagion.”

The collapse of the Soviet Empire remains the formative political experience of Putin’s inner circle, who are haunted by the specter of a similar democratic wave sweeping the present regime away. This is the logic behind the doctrine of intervention that drew Russia into Ukraine in 2014 and led to the current support for Lukashenka. However, there is little love in the Kremlin for the Belarusian strongman. Stepping in to save his regime was an act of pure expediency.

The clearest hint regarding the nature of the recent message conveyed by Lavrov came from Lukashenka himself. Speaking the day after his meeting with the Russian foreign minister, the Belarusian leader appeared to indicate that he was indeed preparing to resign. Many international media outlets seized on Lukashenka’s remarks and reported that he had promised to step down as soon as he had introduced changes to the Belarusian Constitution. In reality, Lukashenka’s words were far more ambiguous and open to interpretation. Specifically, the Belarus leader said: “I am not making a new constitution for myself. With a new constitution, I will no longer work with you as president.”

This comment could mean all manner of things. It may mean that Lukashenka does indeed plan to step down. Equally, it could indicate that he intends to remain as national leader but in a different post under a reorganized constitutional structure. Given Lukashenka’s history as a cunning political operator, the likeliest interpretation is probably that he is playing for time and does not intend on going anywhere at all.

It is reasonable to conclude that Lukashenka’s vague commitment to step down was made under Russian duress. While it generated considerable international media coverage, his statement is unlikely to have convinced anyone in the Kremlin. Instead, Moscow will be expecting to see concrete steps towards a political transition in Minsk.

Likewise, Lukashenka’s domestic opponents were notably unimpressed. In response to his comments, Belarusian pro-democracy activists quickly assembled a long list of Lukashenka’s previous promises to resign. The earliest of these commitments dated back to 2002, when he reportedly stated that eight years in power was already more than enough.

Eurasia Center events

Moscow’s apparent eagerness to push forward with a managed transition of power in Belarus suggests that valuable lessons have been learned from Russia’s heavy-handed and counter-productive approach towards pro-democracy protests and nation-building processes in neighboring Ukraine. Russia’s use of force since 2014 has not achieved the desired outcomes in Kyiv, with Ukraine now firmly set on a path away from the Russian sphere of influence.

The Kremlin is understandably eager to avoid repeating these mistakes in Belarus. There are already indications that Moscow’s backing for Lukashenka is eroding public support in Belarus for closer ties with Russia. A recent survey conducted in early November found that the number of Belarusians who favored alliance with Russia had dropped from 51.6% to 40% in the space of just two months. Once again, Putin’s informal empire is in danger of shrinking.

Russia has an obvious interest in overseeing Lukashenka’s departure, but it remains unclear whether the man himself feels obliged to leave. Throughout his 26-year reign, Lukashenka has made a habit of bluffing the Kremlin, mostly in order to avoid committing to any deepening of bilateral ties in line with the Union State agreement between the two countries. For the past two decades, he has fought tenaciously to keep his realm from being totally consolidated into the Russian Federation. Lukashenka’s slipperiness has become the stuff of legend in post-Soviet political circles, leading many to assume that he will now attempt to backtrack on any earlier promises he may have given to step down.

While Lukashenka’s future intentions remain shrouded in characteristic ambiguity, Lavrov’s recent visit to Minsk leaves little doubt that Russia is losing patience with the Belarusian dictator and has no intention of providing limitless support. Moscow’s attempts to orchestrate a favorable transition in Belarus could also be evidence of an increasingly pragmatic new tone in Russian policy towards the former Soviet republics.

With Russian influence in retreat throughout the region, Moscow no longer appears keen to intervene directly. Instead, we may be witnessing the beginnings of a more nuanced approach that sees Russia in the role of adjudicator rather than enforcer. This was evident in the Kremlin’s ability to skillfully and advantageously direct the outcome of the recent Azerbaijani-Armenian War. Similar thinking now appears to be shaping Russian policy towards Belarus.

Such maneuvering takes time, but Moscow may yet be obliged to force Lukashenka’s hand. With US President-elect Joe Biden committed to supporting the pro-democracy movement in Belarus and threatening to impose tighter sanctions following his January 2021 inauguration, the clock is now ticking. Few in the Kremlin will relish the prospect of entering into a confrontation with the new US President in order to defend one of the world’s most toxic politicians. Lavrov’s visit to Minsk suggests Moscow would much prefer to see a compromise solution in Belarus that would bring Lukashenka’s 26-year reign to a carefully choreographed end. However, Russia now has less than two months to resolve the crisis before the US enters the fray.

Vladislav Davidzon is a nonresident fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Eurasia Center.

Further reading

The views expressed in UkraineAlert are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Atlantic Council, its staff, or its supporters.

The Eurasia Center’s mission is to enhance transatlantic cooperation in promoting stability, democratic values and prosperity in Eurasia, from Eastern Europe and Turkey in the West to the Caucasus, Russia and Central Asia in the East.

Follow us on social media

and support our work

Image: Belarusian President Alyaksandr Lukashenka greets Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov during their November 26 meeting in Minsk. (Nikolai Petrov/BelTA)