By virtually any metric, China is undeniably the world’s solar superpower. It deployed more solar capacity in 2023 than the United States has installed in its history; it also dominates the manufacturing supply chain, especially for wafers. These achievements are remarkable. Yet China’s track record on solar, a critical decarbonization tool, is hardly above criticism, including in its domestic market.

Owing to its deployment patterns and underlying resource constraints, China’s solar usage rates, known as capacity utilization factors, are among the lowest in the world. But this could be about to change. Recent data suggest that China may be shifting from distributed solar to utility-scale solar, which would, all things being equal, raise the overall efficiency of its electricity grid while aiding decarbonization. Given that China is by far both the world’s largest greenhouse gas emitter and coal consumer, its domestic solar deployments will have global consequences. However, several hurdles hindering the country from reaching its domestic solar potential have emerged.

STAY CONNECTED

Sign up for PowerPlay, the Atlantic Council’s bimonthly newsletter keeping you up to date on all facets of the energy transition.

Utility-scale versus distributed solar

China’s domestic solar choices matter because distinct types of solar installations have vastly different generation potentials. Distributed solar, which is typically found on rooftops, lacks the capability to track the sun’s movements and optimize sunlight reception. It therefore has a lower capacity factor than utility-scale solar, which is generally ground-mounted with single- or dual-axis tracking.

Tracking systems typically entail securing bulky frames and motors, and drilling holes to hold the system in place. This type of solar installation is generally not suited for rooftops. Buildings can struggle to structurally bear the weight of tied-down panels, while high winds pose additional risks for rooftop panels. Consequently, rooftop panels typically do not have tracking, which limits their ability to receive optimal amounts of sunlight.

Case in point, in the United States, utility-scale capacity factors in the best locations and with the latest technology, including tracking capabilities, often exceed 30 percent; utilization factors for residential solar average nearly 16 percent. China doesn’t provide a comparable data breakout for its own utility-scale versus distributed solar. It does, however, provide information about its nationwide solar capacity factors. In 2023, China’s solar capacity factors stood at 14.7 percent, versus 23.3 percent in the United States.

China’s lower capacity factors are due, in large part, to its disproportionately high deployment of distributed solar generation relative to utility-scale deployment. There are several potential reasons for China’s tilt toward disturbed solar. China’s best solar resources are in the northern and western parts of the country, relatively distant from the coastal population centers to the south and east, where much of its solar is deployed. Additionally, China has limited interprovincial electricity transfers. These transmission-related factors, along with China’s higher electricity prices for coastal provinces, incentivize rooftop solar deployment in coastal areas, as seen in the chart below.

China’s solar strategy may be shifting away from distributed solar, although the evidence is mixed. In the last quarter of 2023, China reported 58 gigawatts (GW) of utility-scale solar capacity installations, an all-time high and a massive increase from prior periods. In the first quarter of 2024, China once more installed greater amounts of distributed solar capacity than utility-scale solar.

China’s utility-scale breakout?

Some features of China’s potential turn to utility-scale deployments are worth examining. In both 2022 and 2023, China’s utility-scale installations surged in the final quarter, potentially to meet year-end construction deadlines and capacity targets set by national and provincial governments.

Additionally, some provincial-level trends are noteworthy. Hebei, for example, enjoys good solar irradiance, while its proximity to Beijing’s substantial electricity load limits transmission costs. And Yunnan, in southwest China, installation of major utility-scale capacity began at the end of 2023 and continued through the first quarter.

Xinjiang is a striking anomaly. It reports virtually no distributed solar capacity despite having good solar potential, moderate per-capita income, and 34 GW of installed utility-scale capacity (including solar that China attributes to the Xinjiang production corps). Xinjiang’s deployment patterns constitute a major outlier in a country where rooftop deployment has been encouraged through official policy.

The most plausible explanation for this anomaly emerged from a solar expert on China. In written comments to the author, the expert suggested that “If you live in a low rainfall area with dust storms then somebody must keep the panels clean or wipe them down every so often. With a multifamily dwelling a ’crisis of the commons’ issue is quick to emerge.”

While Xinjiang’s lack of distributed solar capacity may be related to several factors, it is also hard not to wonder if the Communist Party’s pervasive repression of the province’s Uyghur population weakens social trust and, consequently, disincentivizes rooftop solar deployments.

Finally, Inner Mongolia’s modest deployment of utility-scale solar has major climate consequences. The sun-soaked, windy province enjoys some of China’s best renewable energy resources, and it is also a coal bastion. In 2023, Inner Mongolia produced 1.21 billion tons of coal supply, of which 945 million tons were supplied to coal-fired power plants, as the renewables-rich province incongruently supplied over 25 percent of China’s coal production last year. Since Inner Mongolia’s thermal coal and solar production compete to provide electrons for the Chinese grid, this province will play an outsized role in shaping China’s climate trajectory.

It’s too soon to say if China is shifting solar deployment into a more efficient model: namely, utility-scale solar in the northern, more sun-soaked regions of the country. Encouraging signs include the planned construction of over 225 “renewable energy bases” across the Chinese interior, comprising total wind and solar capacity of 455 GWs, along with associated transmission lines. Some Chinese provinces are also siting solar panels on land repurposed from mining. These steps are constructive.

Yet there are also reasons to temper expectations. China’s solar utilization rates actually fell in 2023. That may be attributable to the type and regions of deployment, or bad luck from weather, but other factors are possible. With China exhibiting sudden year-end deployment surges to meet construction targets, the long-term performance and sustainment of its panels could degrade if maintenance needs rise. Finally, solar faces economic headwinds in Shanxi, Inner Mongolia, and Shaanxi—some of China’s most sun-soaked provinces. These regions also have an abundance of coal, some of which is used for steel production rather than electricity generation. Still, the fossil fuel keeps electricity prices low, disincentivizing solar.

China is showing signs of a shift toward more utility-scale solar in suitable regions, and it is making substantial progress in deploying massive volumes of solar capacity, but powerful structural hurdles to the technology’s domestic adoption are coming into focus.

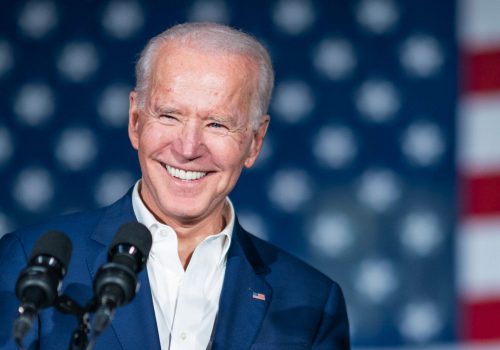

Joe Webster is a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council Global Energy Center, and editor of the China-Russia Report. This article represents his own personal opinion.

MEET THE AUTHOR

RELATED CONTENT

OUR WORK

The Global Energy Center develops and promotes pragmatic and nonpartisan policy solutions designed to advance global energy security, enhance economic opportunity, and accelerate pathways to net-zero emissions.

Image: A solar power plant in Dunhuang. (中国甘肃省酒泉市敦煌, Unsplash)