With Chinese refineries front and center amid price caps on Russian crude and products exports, this article provides fundamental analysis of Chinese refining markets.

Beijing has had a complicated history with its refiners: it attempted to shutter excess capacity at independent refiners (so-called “teapots”) in the 2000s and early 2010s, only to be largely thwarted by provincial and even county-level governments determined to retain the tax base and employment associated with the facilities. Beijing then acquiesced—to a degree—as it relaxed restrictions on import quotas for independent refineries while continuing to consolidate some of the smaller players. While the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has not always achieved its objectives in China’s domestic oil market, it is nevertheless a very active manager, something Western policymakers should consider amid high volumes of Russian crude exports to China.

A brief history of contemporary Chinese refining markets

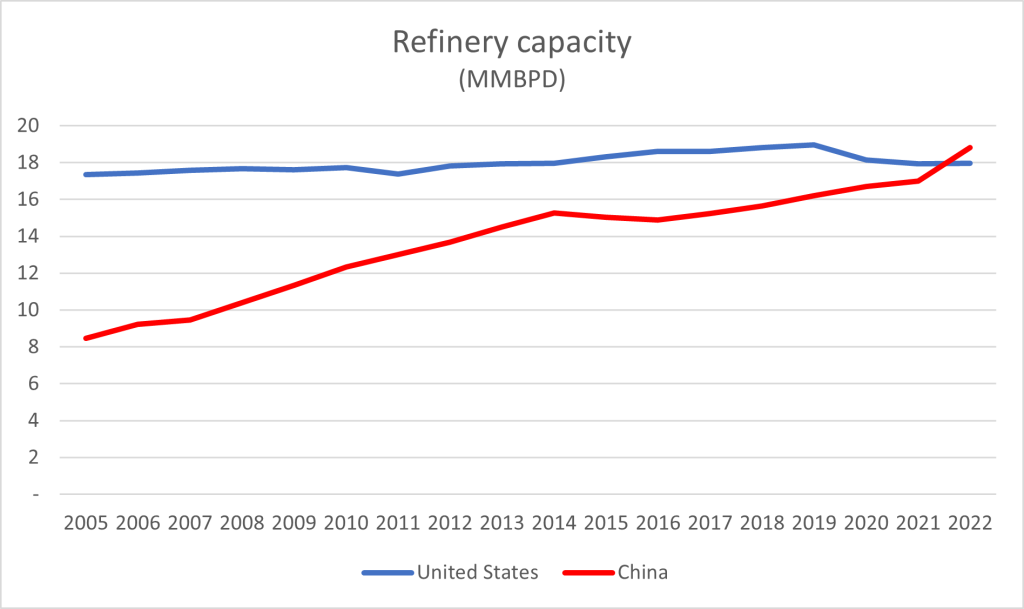

In 2022, China became the world’s largest refining market by capacity, at 18.8 million barrels per day (MMBPD) in 2022. This represents an astonishing increase from 2005, when capacity stood at only 8.5 MMBPD. And the surge is unlikely to stop any time soon, as capacity could grow to 20 MMBPD by 2025, although some analysts see a pullback in domestic refining capacity this year as several outdated facilities are phased out.

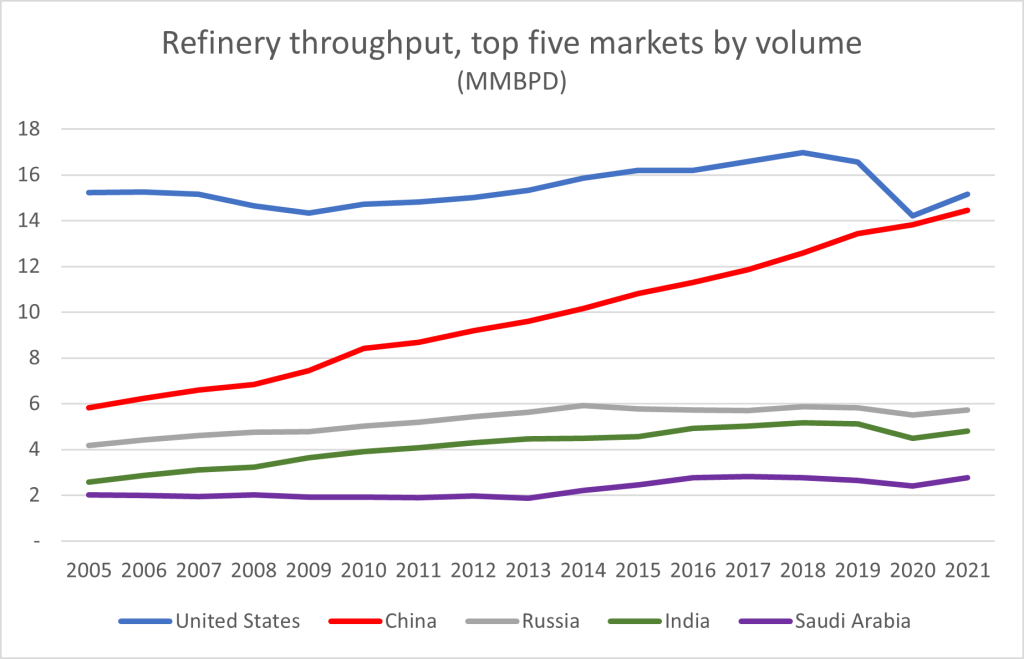

Chinese refinery throughput, or crude oil intake used to produce refined products such as gasoline, diesel, and jet fuel, and more, has expanded along with capacity. While Chinese refinery throughput still lagged the United States in 2021, China is very likely to become the world’s largest refining market within the next two to three years, if it is not already. Chinese refinery throughput stood at just under 6 MMBPD in 2005, but in 2021 reached 14.5 MMBPD, a level just shy of the US throughput of 15.1 MMBPD in the same year.

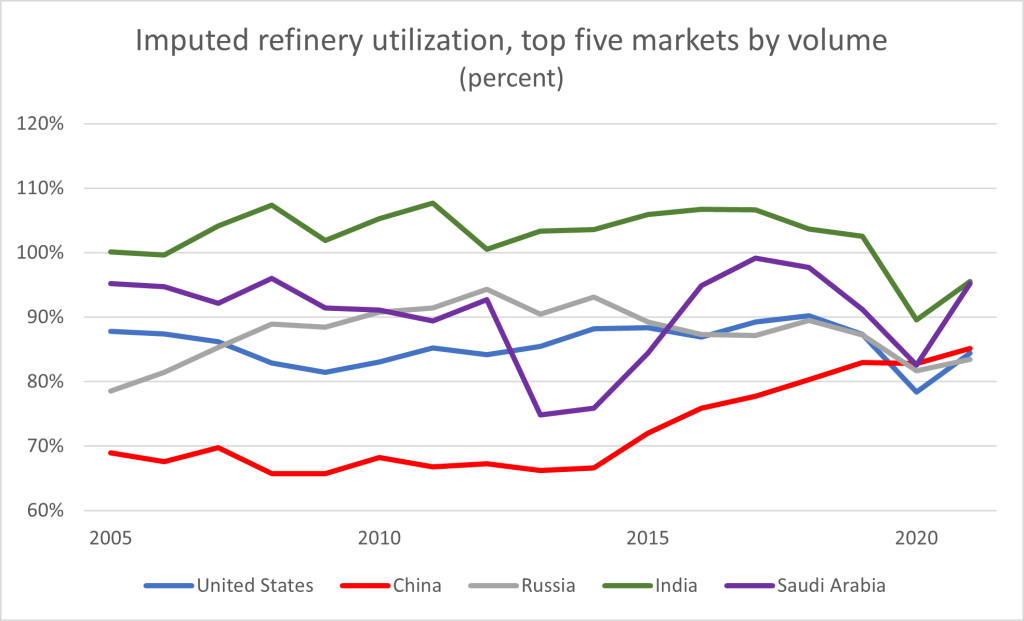

China appears well on its way to becoming the world’s largest and most important refining market, but its journey has been a bumpy one. China’s refineries have traditionally suffered from extremely low utilization rates and poor margins, especially among independent refiners. These refiners are often referred to as “teapot refiners,” due to their limited capacity and basic equipment, especially when compared to refineries run by Chinese national oil companies (NOCs).

These teapot refineries, which are generally privately owned and concentrated in central China’s Shandong province, have historically suffered from extremely low reported utilization rates—often as low as 35 to 40 percent. Extreme overcapacity ensured China historically suffered from ultra-low refinery utilization rates, especially when compared to its peers.

Dragged down by teapot refineries, from 2005-2014, Chinese refineries’ reported collective imputed capacity factors, or “run rates,” hovered at or around 65 percent, the threshold below which most individual US plants tend to shut down, at least temporarily, for economic and safety reasons. Since the entire Chinese refinery sector suffered from low refinery run rates for over a decade, the sector’s overcapacity issues were highly problematic.

Still, it is worth noting that Chinese refineries, especially the independents, are notorious for misclassifying production. There are also recent instances of refineries outright underreporting production to evade taxes. As with all Chinese economic data, one should take presented statistics with a grain of salt.

For much of the 2000s, Beijing struggled to reduce overcapacity. Erica Downs’ The Rise of China’s Independent Refineries traces how Beijing’s attempts to restrain or even constrict Chinese refineries often backfired. For example, in 2009, China’s National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) ordered that all refineries with capacity under 40,000 barrels per day (bpd) be closed, merged, or upgraded, depending on their size. While the policy sought to shutter capacity, refineries, typically with the support of provincial or county-level governments dependent on their employment and revenue, responded by expanding capacity to avoid closure. Between 2005 and 2015, teapots’ refining capacity grew from 832,000 bpd to 4,175,000 bpd, according to Downs, suppressing China’s overall refinery utilization rates.

China’s refining overcapacity problems have abated in recent years due to stabilizing refinery capacity and, more importantly, greater crude imports. The Shandong-based teapots saw some closures and consolidations, including the September 2017 merger of the Shandong Refining Energy Group. Moreover, China allowed independent refiners to import more crude oil—and, typically, export refined products. While China’s four state-owned oil giants—Sinopec, PetroChina, CNOOC and Sinochem—have always enjoyed direct access to crude oil imports, other players, including the independents, are forced to secure import quotas from the central government. Luckily for the teapots (and China’s refinery utilization rates), Shandong’s crude import quotas nearly tripled from 2015 to 2019, while China’s overall crude imports rose from 6.7 MMBPD in 2015 to over 10 MMBPD in 2019. Despite a slight decline in domestic crude production and additional refinery capacity expansions, rising crude imports sent refinery utilization rates higher.

Chinese domestic politics and the oil sector

Chinese domestic also politics played an important role in the evolution of China’s refinery markets. Zhou Yongkang, a former member of the extremely-powerful Politburo Standing Committee, China’s former security czar, and former head of state-run China National Petroleum Company (CNPC, also the parent company of PetroChina), was purged in a Communist Party power struggle amidst the 18th party congress in 2012. Immediately after ascending to General Secretary, Xi Jinping began consolidating power and eliminating rivals, such as Bo Xilai and Bo-affiliated figures, including Zhou Yongkang. The purges ultimately ensnared at least six senior CNPC executives linked to Zhou.

Interestingly, PetroChina’s refinery run rates continue to lag those of Beijing’s other state-run oil companies. Indeed, Shandong independents have occasionally outperformed PetroChina’s refinery utilization rates in recent years. The reasons for PetroChina’s lackluster performance are unclear. While PetroChina’s refining assets are concentrated in less-economically-dynamic north China, constraining its refining economics, the company’s association with Zhou Yongkang could also subject it to additional scrutiny and Beijing’s disfavor. Notably, PetroChina and three independent producers were penalized in early 2022 for “irregular trading.”

The CCP leadership follows oil markets closely

General Secretary Xi Jinping is not nearly as personally engaged with energy markets as his counterpart in Moscow, who has over two decades of experience interacting with Russia’s most important industry and (supposedly) wrote a doctoral thesis on Russia’s natural resources. Still, Beijing’s actions demonstrate is a highly active manager of its refining markets, as its recent decision to lift crude oil import quotas demonstrates. Moreover, Xi is familiar with the sector due to its economic centrality, as well as its role in the Zhou Yongkang affair. The CCP pays close attention to oil markets, something Western policymakers should keep in mind as they examine Sino-Russian energy ties.

Joseph Webster is a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council Global Energy Center.

Meet the author

Related content

Learn more about the Global Energy Center

The Global Energy Center develops and promotes pragmatic and nonpartisan policy solutions designed to advance global energy security, enhance economic opportunity, and accelerate pathways to net-zero emissions.

Image: A refinery. (Tasos Mansour, Unsplash, Unsplash License) https://unsplash.com/license