For years, Eastern European governments and Turkey have bought into a global trend, arguing that long-term strategies in the energy sector should revolve around market deregulation.

In light of the coronavirus outbreak and the emergency measures implemented worldwide to contain it, the energy industry may now face an increase in interventionist policies such as price controls and consolidation of state-owned enterprises as governments push to mitigate the shockwaves of expected consumer impacts.

Such measures would be detrimental to economies, and there are compelling arguments that suggest governments should remain committed to their initial market goals.

Countries in the region initially implemented energy sector reform to improve economic efficiency or clamp down on mismanagement that had left them vulnerable to corruption as well as Russian political influence. These goals are unlikely to lose their relevance going forward.

As energy consumption is expected to fall some 20 percent on pre-pandemic levels, natural gas prices —which have experienced a downward trend as a result of global oversupply—will be further compressed.

By capping energy prices, governments may not be much help to consumers; free-market prices would already be low, straining weakened budgets and discouraging investors at a time when they are most needed.

Rather than attempting to halt or reverse the deregulation of energy prices, state institutions should, instead, look at the coronavirus crisis as an opportunity to legitimize such efforts.

Governments in this part of the world have lost much of their credibility as result of political infighting, corruption, and incompetence that have consequently led to unpredictable and unreliable business environments.

As companies and consumers now turn to state governments to guide them through troubled times, national leaders have a fresh opportunity to regain credibility; first by acknowledging that past failures have largely been linked to lack of trust in their actions and institutions, and second, by firmly committing to reform goals, market competition, and transparency.

Acknowledging failures

Although energy market reform began approximately at the same time in Eastern as it did in Western Europe, the former trails the latter.

Expert literature has identified a lack of resources, poorly diversified supply routes, and the Kremlin’s political influence as the underlying reasons for this discrepancy.

Given the recent construction of pipelines such as the Southern Gas Corridor and TurkStream, as well as the import of liquefied natural gas (LNG) to the region, it is hard to argue that a lack of resources and routes accounts for the shortcomings.

It is true that Russia continues to perpetuate a culture of corruption in the East, but that may not explain the whole picture. Part of the blame also lies with the individual countries’ inability to establish and cultivate public trust.

For example, Romania had attracted US oil major ExxonMobil and Austria’s OMV to develop some of its offshore Black Sea gas reserves, but both ExxonMobil and OMV may now abandon the project, discouraged by unpredictable regulations and a generally unfriendly business environment.

Although Ukraine has made good progress in reforming its gas sector and tightening up governance in state institutions, it has failed to attract high-profile companies to explore its oil and gas resources. Investors remain daunted by similarly unpredictable regulations and political instability.

Years of government meddling and currency volatility have left Turkish energy companies facing multi-billion-dollar debt. The Turkish energy sector requires urgent restructuring and investment, but many companies have left, discouraged by state intervention: price controls, unpredictable government regulation, and property nationalization.

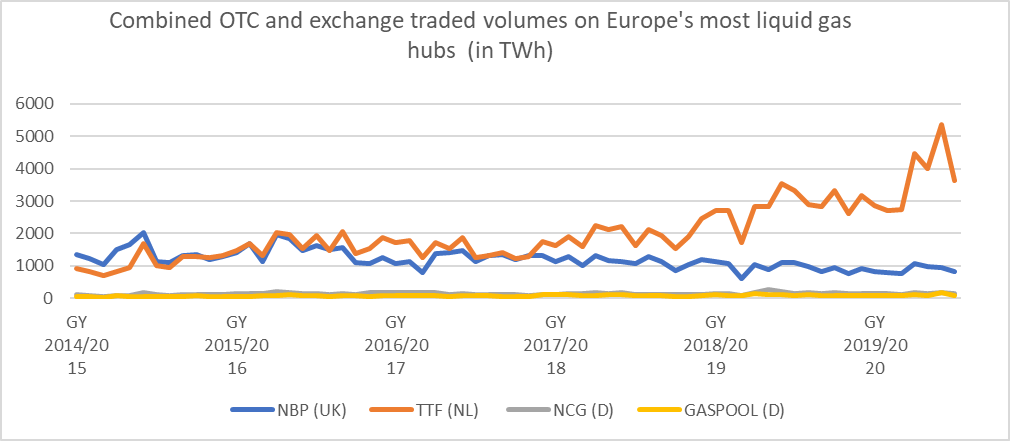

In contrast to Eastern Europe and Turkey, where markets are burdened with litigation and subject to constant regulation, the Dutch gas market, a global reference point with predictable rules and reliable institutions, serves as an example to follow.

In March 2020, for example, combined over-the-counter (OTC) and exchange gas volumes traded on the Dutch hub, known as the Title Transfer Facility (TTF), soared to a record 5,371 terawatt-hours (TWh), 34 percent up year-on-year. TTF now accounts for over 70 percent of European spot trading, according to details collated by energy data and news provider Independent Commodity Intelligence Services (ICIS).

The hub’s heightened importance comes at a time when the Dutch Groningen gas field, Europe’s largest onshore source of domestic gas, is drying up, slated for shutdown by 2022.

Source: Produced with data compiled by ICIS

Although the current coronavirus crisis has affected all gas markets, including the Dutch market—where demand fell some fifteen million cubic meters (mcm) within a month of emergency measures being put in place in mid-March—it is reasonable to expect that the Netherlands’ credible institutions and predictable rules will help it remain the most liquid gas hub in Europe, at least for the foreseeable future.

Regaining trust

While the upcoming months will be difficult, Eastern European governments and Turkey must use the current context to enact several important measures.

To start, they must reiterate their commitment to an agreed liberalization calendar.

Despite its significant progress on reform, Ukraine is still short of removing a natural gas subsidies scheme for households and district heaters that has so far put a strain on the national budget and encouraged corrupt practices. The public service obligation was expected to be phased out in May but has now been partially delayed for households until July 1, 2020, and for district heaters until the second quarter of 2021.

The Romanian government must take similar steps to deregulate gas prices by July 1, 2020, and electricity prices by January 1, 2021, as agreed with the European Union.

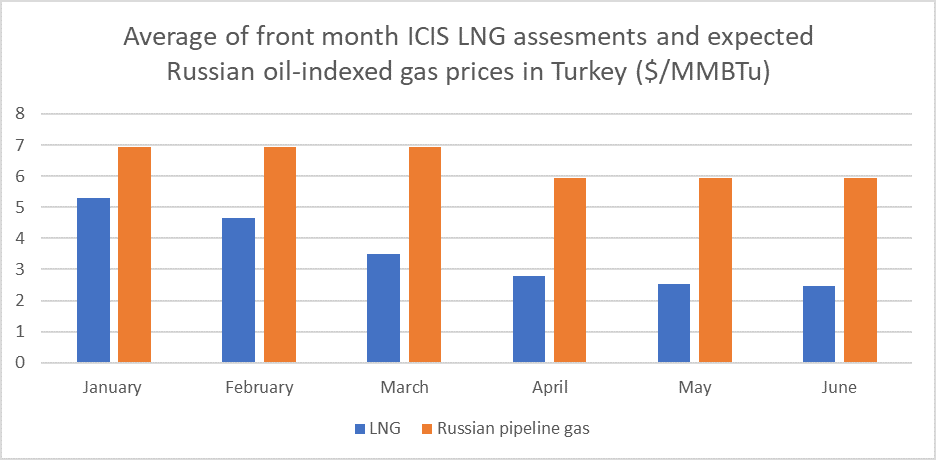

Meanwhile, the Turkish government should guarantee incentives such as transparent tariffs and import slots at LNG terminals to allow not just the state company BOTAS but also private players to take advantage of cheap LNG. Currently, BOTAS imports spot LNG at a $3.00/million British Thermal Units (MMBtu) discount to Russian pipeline gas, but that option is not available to private firms, as the market remains firmly concentrated in the state company’s hands.

Source: Produced with data compiled by ICIS

Finally, regional governments must ensure that, while many small to medium-sized producers or suppliers may go bankrupt as a result of current conditions, larger players will not take advantage of the situation to expand their market positions in a way that blocks competition.

Dr. Aura Sabadus is a senior energy journalist who writes about Eastern Europe, Turkey, and Ukraine for Independent Commodity Intelligence Services (ICIS), a London-based global energy and petrochemicals news and market data provider. You can follow her on Twitter @ASabadus

Read more from this author

Learn more about the Global Energy Center

The Global Energy Center develops and promotes pragmatic and nonpartisan policy solutions designed to advance global energy security, enhance economic opportunity, and accelerate pathways to net-zero emissions.

Image: The Danube spills into the Black Sea (The Sea WiFS Project/NASA Earth Observatory/Wikimedia Commons)