While the mainstream media’s attention is now focused on the completion of Russia’s two gas pipeline projects—Nord Stream 2 and TurkStream—exceptional, but under-reported changes are afoot in southeast Europe that could challenge Moscow’s regional dominance and geopolitical pressure and help establish a bidirectional north-south corridor linking Greece and Turkey to Ukraine along the Trans-Balkan pipeline.

The corridor has been the main artery for gas shipped from Russia to Bulgaria, Greece, the Republic of North Macedonia, and Turkey across Ukraine, the Republic of Moldova, and Romania for more than three decades.

However, with a long-term transit contract between the Ukrainian incumbent Naftogaz and Russia’s Gazprom expiring at the end of 2019, and Moscow pressing to divert current exports to TurkStream 1 and 2, an entirely new transport route across the Black Sea, the Trans-Balkan pipeline is expected to be freed up.

Critically, the expiry of the contract coincides with a rise in US-sourced liquefied natural gas (LNG) exports to Greece and Turkey and unprecedented transformations in the region’s gas dynamics.

This opens a rare window of opportunity for southeast Europe—historically one of the continent’s areas most reliant on Russian gas—to tap LNG and transport the fuel from south to north across the Trans-Balkan route.

To reverse flows, countries would need to boost compression, upgrade metering stations, and align transmission and cross-border trading rules. But while the costs involved in such operations are relatively small and the time required to implement them should be short, particularly when compared to building a new pipeline from scratch, the difficulty lies in countries agreeing to work fast and in concert before the window of opportunity closes and Russia’s grip is further cemented.

Transformations

Since the beginning of 2019, southeast Europe and Turkey have witnessed some of the most dramatic gas sector changes in recent years.

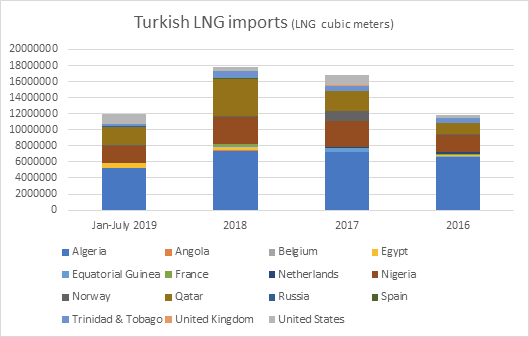

Turkey, which has traditionally relied on Russian pipeline gas to cover more than half of its internal consumption, has succeeded in raising its LNG off-takes to be almost on par with Russia’s shares of Turkey’s total imports. According to latest reports by the energy regulator EPDK, Turkey imported 20.6 billion cubic meters (bcm) of LNG and pipeline gas in the first five months of 2019. Of these, 6.8 bcm, or 33 percent, were Russian pipeline gas, while LNG imports amounted to 6.5 bcm, or 32 percent, of the total. This is a remarkable change from the first five months of 2017, for example, when Turkey’s pipeline imports from Russia stood at 51 percent of total gas off-takes, which amounted to 24.2 bcm. To compare, the share of LNG within the total imports stood at 21 percent during that same period.

Within Turkey’s rising share of LNG imports, US deliveries have been soaring. According to the same reports, the country off-took 0.9 bcm of US-sourced LNG in the first four months of 2019, which was double the volume of US imported LNG throughout the whole of 2018.

The significant increase in US-sourced LNG now places Turkey after Spain as Europe’s second largest importer.

Changes are largely due to the recent expansion of Turkey’s LNG import capacity at its onshore Aliaga and Marmara terminals and the charter of two floating storage and regasification units (FSRU), which serve its Etki and Dortyol ports on the Aegean and Mediterranean Seas. The expansion has brought its total nameplate LNG import capacity to 42.7 bcm, or 90 percent of Turkey’s total gas imports in 2018, strengthening Turkey’s position as a major global LNG importer and as an aspiring regional gas hub.

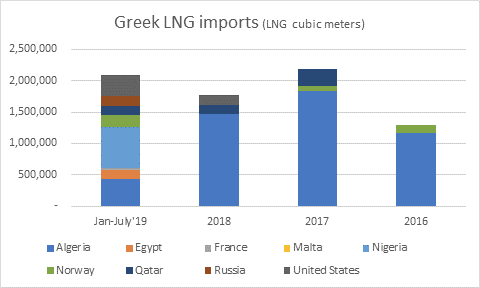

Neighboring Greece has equally expanded its importing capacity at the Revithoussa LNG terminal by adding a third tank and is in the process of commissioning an offshore terminal at the northern Alexandroupolis port.

Like Turkey, it also imported more US-sourced LNG in the first half of 2019 than throughout the whole of 2018, as shown in the graph below.

Earlier in June, for the first time ever, Greece received a US-sourced LNG cargo for delivery into Bulgaria, which was due to be followed by a second delivery via the same Greek onshore Revithoussa terminal in the third quarter of 2019.

Bulgaria, which had depended almost entirely on Russian gas until recently, has been able to diversify supplies thanks to the arrival of US LNG and the increase of cross-border physical interconnection capacity at its Greek Kulata-Sidirokastro interconnection point. The interconnection capacity between the two countries is set to rise further in 2020 when the 3 bcm/year Interconnector-Greece-Bulgaria (IGB) will be commissioned and linked to the Alexandroupolis terminal in northern Greece.

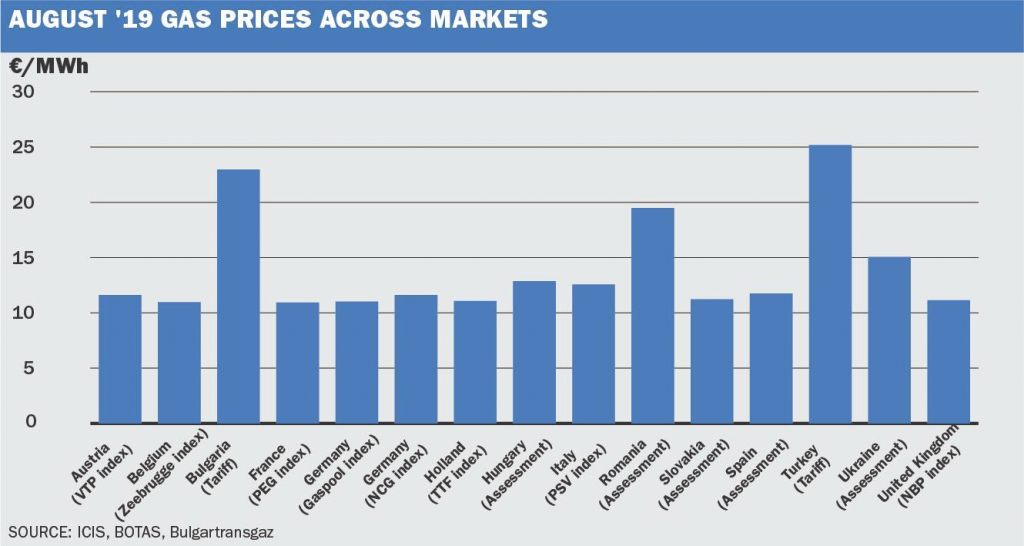

From a pricing perspective, the region currently carries a premium of anything between €9.00–€14.00/MWh ($2.98/MMBTu–$4.6/MMBtu) over western Europe. In Bulgaria and Turkey’s case, this is because they operate regulated end-consumer tariffs, which reflect the price of Russian oil-indexed gas imports. As for Romania, the government reversed the liberalization process this year, capping end-consumer tariffs and introducing an import obligation despite reduced interconnection capacity with neighboring markets.

The high costs paid by these countries for natural gas makes it even more imperative for them to open up their borders and allow LNG to reach their markets, while LNG companies should be attracted to sell to this premium region at a time of globally reduced profits.

The milestones reached and dynamics currently shaping up are only the beginning of a wider regional transformation that could see LNG reaching markets as far north as Romania, the Republic of Moldova, and Ukraine if transmission capacity is made available on the Trans-Balkan pipeline.

Obstacles

In 2020, when Gazprom’s transit contract with Ukraine’s incumbent Naftogaz ends, volumes currently exported via the Trans-Balkan pipeline to Turkey may be diverted to the 15.75 bcm/year Russian-backed TurkStream 1 to serve the Turkish market exclusively.

Russia’s TurkStream 2, a pipeline of equal capacity, is expected to carry gas to Hungary via Turkey, Bulgaria, and Serbia. However, there are indications that the project—which will rely on existing infrastructure, some of which is part of the Trans-Balkan line, as well as new pipelines built inside Bulgaria—will be delayed at least until 2021 due to ongoing legal issues in that country.

This means that if the 14 bcm/year of gas exported to Turkey via the Trans-Balkan line are diverted to TurkStreamm1, then most of the existing transit infrastructure could become idle, allowing countries along the route to reverse flows and establish a bidirectional corridor.

Until the completion of TurkStream 2, Gazprom may continue to transport some smaller volumes via the Trans-Balkan corridor to countries such as Bulgaria and Greece, which hold long-term supply contracts not exceeding 3 bcm/year each.

Even so, capacity could be booked by other companies in reverse flow on the Turkish-Bulgarian section of the line following relevant upgrades last year. Spare capacity on T1, one of the three lines of the Trans-Balkan corridor that links Romania’s Bulgarian border to its interconnection point with Ukraine along the same route should also be available.

With import and transit capacity expanded in Turkey and Greece, and Ankara looking to sign an interconnection agreement with Sofia to allow Turkish exports, LNG could reach the entire region as early as January 1, 2020.

Nevertheless, there are lingering obstacles that have to be removed.

While carrying out the technical works—for example, boosting compression or introducing new metering stations—should not be a challenge in itself, the difficulty lies in stakeholders along the route working in unison to turn the Trans-Balkan pipeline into an export corridor for LNG and an alternative to Russia’s regional projects.

So far, countries such as Romania have proven reluctant partners, being accused by the European Union (EU) of hampering regional gas security by restricting cross-border trading.

Romania’s transmission system operator, Transgaz, has also failed to implement EU rules for third party access at its interconnection point with Ukraine following the expiry of the T1 transit contract in 2016, despite high interest in capacity booking at that interconnection point.

The region may have until 2021, the likely date by which Bulgaria is expected to sort out legal issues and build its leg of the TurkStream 2 corridor, to ensure it establishes access to non-Russian supplies and infrastructure to create real change.

If that window is missed, the TurkStream 2 corridor will be commissioned and critical infrastructure would once again be blocked to serve Gazprom’s interests.

Dr. Aura Sabadus is a senior energy journalist writing about Eastern Europe, Turkey, and Ukraine for ICIS, a London-based global energy and petrochemicals news and market data provider. You can follow her on Twitter @ASabadus

Image: Source: ENTSOG Transmission Capacity Map 2017.