Iran’s ‘butterfly children’ impacted by sanctions and corruption

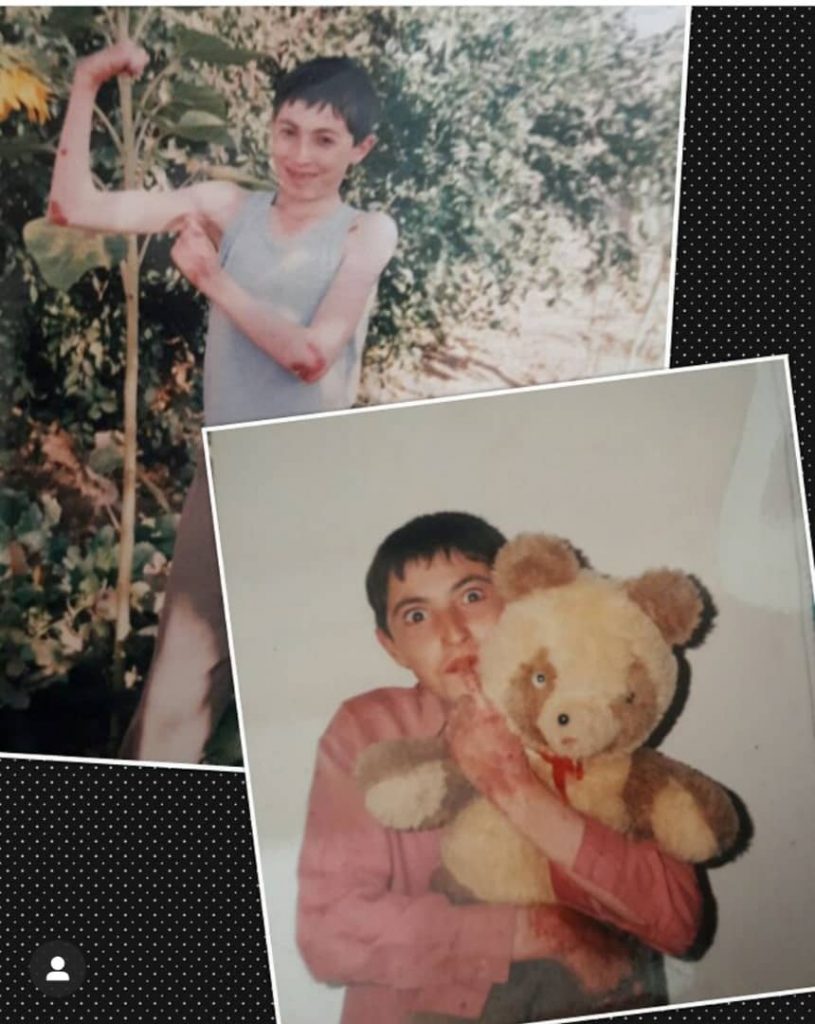

In October 2017, Adel Zadeh, a 27-year-old student from Ardabil in northwestern Iran, watched in horror as the fingers on his right hand began fusing together.

Scores of fluid-filled blisters on his skin had burst and become infected. But unlike typical blisters that pop and are immediately replaced by scar tissue, these sores caused his fingers to stick to one another and curl in. His hand suddenly became a permanent fist. His older sister, 46-year-old Masomeh, had the same symptoms.

That fall, both siblings underwent a five-hour hand and finger separation surgery, which they described as unbearably painful. But the worst had yet to come.

“Afterwards, it was even more excruciating to change my dressing twice a week,” said Adel. “Both of us had to be anesthetized for about an hour each time.”

The surgery was Adel’s third operation over seven years; each relating to a rare skin disorder they had inherited called Epidermolysis Bullosa (EB).

Described by US dermatologists as “the most painful disease you’ve never heard of,” EB is caused by a genetic mutation and occurs in every 1 in 30,000 to 50,000 live births globally. Characterised by extreme fragility of the skin and mechanically induced blistering, EB patients are often referred to as ‘butterfly children’ because their skin appears as delicate as that of a butterfly wing. There is no cure.

The only relief patients receive on a daily basis is through specialized foam dressings that reduce and protect blisters. The most effective dressings are produced by the Swedish pharmaceutical company Mölnlycke and are used by EB patients worldwide.

But for patients in Iran, where an estimated 800 to 1,200 patients live with EB at any given time, access to Mölnlycke supplies over the last two years has been next to impossible. Though US sanctions on Iran exempt humanitarian goods, sanctions on Iranian banks have drastically restricted Tehran’s ability to finance humanitarian imports, impacting patients who suffer from critical or rare diseases, from EB to epilepsy to cancer. A Human Rights Watch report from October 2019 references a letter sent by Swedish Mölnlycke to EB Home, Iran’s largest NGO supporting EB patients, that confirmed the company had decided not to conduct any business with Iran due to US sanctions. According to EB Home, at least fifteen children with the disease died over the last year.

“I used to receive a pack of required supplies every month,” Adel recalls. “This would only be enough for two weeks—not a month. Nonetheless, many people had a worse situation than me. I was a moderate case.”

In May, UNICEF made a surprise announcement that offered a sliver of hope: A German-financed shipment of wound dressings from Mölnlycke had been procured and shipped to Tehran. (Separate reports suggest that the shipment had started earlier in December 2019.)

“The one-time shipment of wound dressings weighs 5.8 metric tons, and will be delivered to Iran’s Health Ministry for handover to the EB Home Foundation,” Iran’s UNICEF office stated in a news release on May 12.

Upon hearing the news, both Adel and Javad Karami*, who has a younger brother with EB in Tehran, expressed mixed feelings—relief that their cries for aid were finally being heard and fear that the supplies would disappear into the black market, making them unaffordable or inaccessible.

“There should be complete supervision over the distribution process because there is a definite history of hijacking such enormous cargos,” Javad, a 22-year-old medical student at Tehran University, explained.

His concerns echo the rage of thousands of the country’s healthcare workers and the chaos they have found themselves in since February, as the number of black market traders hoarding medical supplies surged, especially, over COVID-19 equipment.

“The reality is that corruption, by way of the black market being created for a specific drug that is in demand, exists primarily because the government is trying to ensure that the costs of medication are kept regulated and are affordable to everyone,” said Vira Ameli, a public health researcher at Oxford University. Iran’s Health Ministry provides free treatment services for registered EB patients.

“So, when sanctions happen… or there’s suddenly a pandemic, the medications for that disease are not imported as readily as before. That’s what leads to black market creation, which is a characteristic of economies under sanctions. Sanctions create scarcity,” Ameli adds.

Not surprisingly, it is Iran’s most vulnerable that suffer. “It makes me incredibly upset because I know between the two governments, neither get hurt by these sanctions,” says Adel, the EB patient. “It’s only ordinary people like myself who get hurt. I cannot find the medical supplies I need—and if I find them the prices have increased so much.”

The UNICEF-Mölnlycke shipment also comes at a time when need is at its peak. The situation had become so dire that independent Iranian activists in the US and Europe have been helping to alleviate the shortage by sending pre-ordered dressings and bandages with travelers to Iran. Coronavirus travel restrictions have made even this means of passage impossible.

EB patients live with constant pain and stress, especially, those with more severe forms of the disease. These patients often require extensive bandaging from head to toe and are at risk of malnutrition and esophageal strictures. Bathing and wound management can take 3-5 hours at a time. Even the slightest knock or touch can trigger painful blistering. Known as recessive dystrophic EB, this is the category Javad’s brother, Reza*, falls into.

“Every part of the body that has skin is affected,” he says. “He’s 15 years old and every day of it has been a challenge to live.”

“The Mepilex patches from Sweden are really the only means through which he can stay alive. When we stopped receiving supplies, we had to buy less high-quality products that get stuck to the skin and make the wounds worse.”

So desperate is the family to obtain proper dressings that they have been repeatedly applying the one single-use Mepilex patch they managed to obtain recently by cleaning it with alcohol.

“I don’t care whose fault it is,” Javad says in reference to political tensions between the US and Iran. “Obtaining the right supplies is tiring; it needs much effort. As a middle-class family, we have the best conditions an EB child can have in Iran. We don’t feel the problem as hard as others. Can you consider how conditions would be for a family in a village south of Iran?”

Javad likens the lack of Mepilex dressings for EB patients to the slow killing of a vulnerable population. “Committing a murder doesn’t just look like people being killed ISIS-style. I think the most powerful political men in the world don’t really care about things like this. What is this [blockage of medical supplies] for?”

Despite the struggles, Javad describes Reza as an excellent communicator and deeply astute, even though he never attended school. Medical researchers also attest to this—that for all the physical limitations EB patients have, they often exhibit above-average intelligence.

“Children with EB are really smart. I don’t know if it’s based on their genes or their experiences of life, but they are philosophers of life. They feel the worst and most painful parts of life in every moment. Moments in which they feel no pain are really valuable for them.” On his better days, Javad says, they play games and table tennis together.

Despite suffering long bouts of depression and bullying as a child, Adel pushed ahead to complete two degrees, and is optimistic about his future.

Meanwhile, Adel, who was born with a milder form of EB that has gotten progressively worse over time, shares a different educational experience. Having graduated with an undergraduate degree in 2016, he is looking forward to defending his Master’s thesis in biomedical engineering from Tabriz Azad University in the fall.

His academic achievements are the culmination of years of hard work and resilience in the face of adversity. “The hardest part of my elementary and middle school years was living in the mountainous area of Lombar Village [in northwestern Iran]. The area is full of snow, ice, and rocks and I would fall down and the wounds got worse,” he recalls.

Adel’s years in high school were no better, given the lack of public awareness around EB. “When I entered high school, no one knew about our illness, so they asked a lot of questions. I was very upset at the time and covered myself completely and put on gloves.”

“One day the principal told my father to come to school,” he explains. “He told him that because of my illness, the other students were complaining because my wounds smelled. I was told to leave school, to which I objected. But I got very depressed. I fell behind in my studies but stayed there… and dragged myself towards graduation.”

Today Adel lives with the hope that a cure for EB will be found one day. He’s optimistic about the future and dreams of working and travelling.

“I have a lot of dreams, one of which is to be able to have a good job in my field after graduating from university, in order to compensate for the efforts of my dear parents. I want to make a beautiful life for myself.”

*Names have been changed

Shenaz Kermalli is a freelance writer and journalism instructor at University of Toronto and Ryerson School of Journalism. Follow her on Twitter: @mskermalli.

Image: Adel graduated in 2016 with an undergraduate degree in Biomedical Engineering from Azad Islamic University of Ardabil.