US-Iran relations: A cloudy 2020 forecast

The United States and Iran are facing a new year of deepening hostility and games of brinkmanship with scant opportunities for a diplomatic exit.

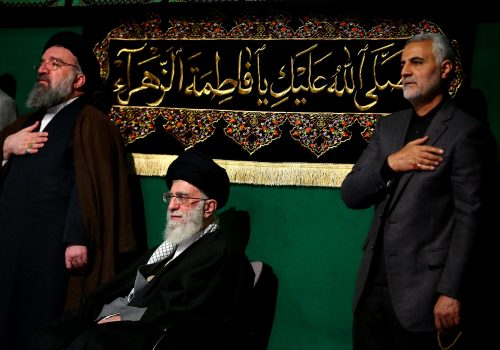

The Trump administration’s unilateral decision to abrogate the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) and to implement a “maximum pressure” strategy, with the alleged aim of bringing Iran back to negotiations for a “better deal,” has instead incentivized Iran to respond with aggressive actions against US allies in the Persian Gulf and, through proxies, against US personnel in Iraq and Syria. The assassination of General Qasem Soleimani, the commander of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC)’s Quds Force has further set into motion, an unprecedented escalatory pattern between the countries, which culminated by Iran’s ballistic missile strikes against US forces in Iraq.

The assassination of the Iranian commander, was met with a unified front among different political factions in Iran, all calling for a “severe revenge.” Meanwhile, the decision makers in Tehran facing a dilemma of doing nothing in response to a humiliating attack on their celebrity General, or to risk a potential war with the United States, opted for a face-saving and “proportionate” response that avoided any American casualties, while sending a strong warning. Fortunately, Tehran’s launch of a dozen ballistic missiles did not cost any lives sparing both countries from the possibility of an all-out war. While it seems that tensions have slightly eased, the Trump administration will have an extremely difficult- next to impossible- task of convincing Iranians to come back to the negotiation table and negotiate a “better” deal.

Furthermore, on January 5,the Iranian government announced the final step of reducing its commitments under the nuclear deal, removing all technical limitations that it had previously accepted under the JCPOA. Ironically, the Trump administration had previously used the eventual lifting of technical limitations- or the sunset clauses- in the year 2030 as a pretext to abrogate the nuclear agreement with Iran. At this point however, Iran has proclaimed that it will come back into full compliance if other signatories, especially the EU fulfill their commitments under the nuclear deal.

To make matters even worse, domestic politics in both countries are likely to work against any de-escalation, and the region will remain tense as the world waits to see if Donald Trump is re-elected as the president.

Recent demonstrations in Iran during November 2019 sparked after gasoline price hikes, and the regime’s decision to use brutal force to quell the demonstrations, will also impact US-Iran relations in 2020. While it was the decision by the administration of Iranian President Hassan Rouhani to abruptly increase prices by 300 percent that brought people to the streets, the protests quickly turned political with anti-regime slogans. Amnesty International reported that at least 300 people were killed and thousands arrested. The government also shut down the Internet for five days in an effort to suppress the demonstrations. The ensuing uproar over the bloodshed will likely constrain any possibility that the US could offer Iran sanctions relief.

Adding even more fuel to the fire, was the shooting down of the Ukrainian passenger aircraft which cost the lives of 176 people onboard, including many Iranians. After three days of denial, the Iranian government finally admitted to the accidental shootdown. However, the initial denials and the tragic loss of many lives have brought many people to the streets again, provoking another series of crackdown on protestors.

These demonstrations are likely to undermine Iran’s ability and willingness to engage in serious talks with the US, as Tehran would prefer to avoid appearing weak and desperate. While in December 2019 Iran and the US successfully exchanged two prisoners, and Iran’s Foreign Minister Javad Zarif expressed Tehran’s willingness for a comprehensive swap, it is unlikely that the two sides will achieve a major breakthrough in what is for both a politically consequential year.

A critical factor is that President Trump is seeking re-election against a yet-to-be determined Democratic candidate in November. While Iranian officials including Zarif have publicly rejected the notion that Tehran is waiting for the results of the US elections, it would seem rational for Tehran to refrain from serious talks with the US until the results of the presidential vote are known and, possibly, a new US president has taken office. Meanwhile, Zarif has stated that Tehran will be making its decisions under the assumption that Trump will win a second term in the office. US presidents in their second and final terms typically have more flexibility for bold action, particularly in foreign affairs.

While the United States chooses a president, Iran will be entering its own election cycle beginning with the choice of a new parliament in February. Persian-language media has already reported that many reformist-leaning candidates, including some currently serving in the parliament, have been barred from running for re-election. Such vetting by the hardline Guardian Council, coupled with growing popular disenchantment with the reform movement—which has failed to deliver on its promises for more political and social freedoms—will likely pave the way for the resurgence of hardliners, who have historically opposed engagement with the West.

Meanwhile in 2021, Iran holds its thirteenth presidential election. Rouhani who ran on the promise of engagement with the West as the remedy for Iran’s economic doldrums, will be constitutionally barred from seeking a third consecutive term. In this context, Rouhani, who is facing strong criticism for not delivering on his promises for economic recovery and political reform, is a marginalized lame duck. Thus, his ability to achieve a new breakthrough with the US will be minimal and both capitals will be preoccupied with political transitions.

The US decision to unilaterally abrogate its commitments under the nuclear deal has already bolstered the position of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and the IRGC, whose interests lie in perpetuating an adversarial relationship with the US. In August 2018, Khamenei stated that the experience of JCPOA shows that “Iran cannot reach an understanding with the US… because they don’t abide by their commitments.” A year later, he officially banned any talks with the American officials. When Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe visited Iran in June 2019 to try to mediate between the two countries, Khamenei publicly rebuked the US president by stating that Trump is not “worthy” of exchanging messages.

Nevertheless, Rouhani’s visit to Japan in December 2019 raised some speculation that the Iranian president might still seek a return to talks if the Trump administration were willing to offer sanctions relief. Furthermore, while reports indicated that Zarif would be traveling to New York on January 9 to attend a UN Security Council meeting, the State Department denied the top Iranian diplomat a visa, citing late visa application submission.

Perhaps the most significant achievement of the JCPOA was that after four decades of enmity, the agreement created a platform for the US and Iran to meet and talk on a regular basis. However, President Trump’s decision to withdraw from the deal eliminated that platform. Given the ongoing tensions, it seems that the year 2020 will be a diplomatically barren year in US-Iran relations, with both sides well dug into their positions.

In the age of Twitter diplomacy, a breakthrough from the vicious cycle of US-Iran hostility would require statesmen in both capitals with the vision to break the stalemate and the courage to resist attacks from those who have become accustomed to—and profited from—decades of enmity.

Sina Azodi is a PhD candidate in international relations at University of South Florida. He is also a foreign policy advisor at Gulf State Analytics, a Washington-based geopolitical consultancy firm. Follow him on Twitter: @azodiac83.

Image: A demonstrator holds a picture of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei with Major General Qasem Soleimani during a protest on January 3, 2020 (Reuters)