China’s Persian Gulf strategy: Keep Tehran and Riyadh content

China’s Persian Gulf strategy is based on building economic ties with all regional actors, regardless of existing rivalries. When it comes to the Gulf, the Chinese approach is mainly driven by Beijing’s voracious energy appetite and its ambitious expansion through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Politically, China has, so far, been reluctant to become involved in the regional disputes.

This apolitical logic is important for China in order to remain neutral in regional power disparities, despite the strategic nature of the infrastructural and economic links built under the umbrella of the BRI. This allows China the almost impossible—which is to expand its economic and military activities in a highly competitive environment—without being bogged down in the turmoil of regional, political and security conflicts. However, the success and consolidation of this strategy seems to be bound to a minimum degree of stability in the Persian Gulf.

Indeed, escalations—such as the one that followed the January 3 killing of Quds Force Commander Qasem Soleimani, or the 2018 US withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA)—force China to take a more proactive stance and expand its economic focus towards a security and geopolitical level. Regardless of the reason Soleimani was killed, the turmoil following his death will likely result in a more unstable environment in the Persian Gulf—a situation that could have devastating economic consequences for Beijing. Against this backdrop, the question of whether China pursues strategic hedging in the region has taken on new relevance.

Since the expiration of US waivers on Iranian oil imports in May 2019, China continued importing a small but consistent quantity of Iran’s petroleum. According to reports, China imported around 186,000 bpd in June 2019, the amount dropping to 105,000-186,000 by August 2019. While Iran was pushing for an acceleration in Sino-Iranian relations, China has so far remained consistent with the path taken since summer 2019, as the December trade data show. It appears that, beyond possible technical reasons related to the quality of the Iranian crude, Beijing is offering a lifeline to Tehran in defiance of US oil sanctions partly as an attempt to appease Iran and avoid a full-scale conflict in the Persian Gulf. Along with this strategy, China leans on using supportive language in regards to Iran, by accusing the United States of being primarily responsible for the growing tensions in the Gulf, and openly condemning Washington’s military adventurism in the region. With that in mind, Saudi Arabia, Iran’s longstanding regional rival, strategically seems to accept China’s defiance of US sanctions and supportive language vis-à-vis Tehran. This piece assesses what this implies for China-Gulf relations, focusing on the Beijing-Riyadh axis.

In general, China-Gulf relations are evolving within a context that is characterized by global and regional geopolitical power transitions. For a long time, political-security arrangements in the Persian Gulf region had been based on a “balance of power” among countries such as Iran and the United States. Moreover, there have been major changes in international energy markets and a deteriorating security situation in the region that has once more become subject to geopolitical tensions. In order to understand the rationale and implications of China’s stance towards the Persian Gulf countries as well as the scope and degree of the Gulf monarchies’ reaction to China’s deepening ties with Iran, it is necessary to dive into each of these dimensions.

Aforementioned, China has established comprehensive strategic partnerships with Saudi Arabia since 2016 and the United Arab Emirates since 2018. According to the China Global Investment Tracker, Beijing’s investments in the two countries between 2008 and 2019 reached a total of $62.55 billion, while the total amount that China invested in all the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries during the same period is around $83 billion. Current developments notwithstanding, this puts the Gulf monarchies into the center of Beijing’s economic projection towards the Middle East. Against the backdrop of China’s growing hunger for oil, it is not surprising that most Chinese investments in Saudi Arabia and the UAE were made in the energy sector, albeit not solely.

With a high volume of trade between China and the Gulf countries that reached $197 billion in 2017, the level of economic interdependence between Beijing and the Persian Gulf is significant even beyond the oil and energy sector. Undoubtedly, this has a direct impact on how China deals with tensions in the region, as well as on how the Gulf monarchies view the Chinese response—especially given that Saudi Arabia is reaching out to non-regional players in order to diversify their economies and move beyond single-resource rentier incomes. China’s growing hunger for oil comes at a well-needed point in time, after the price drop in energy markets had badly shaken the economies of the Gulf monarchies. Not only is China dependent on oil imports, but Gulf countries are also heavily reliant on energy exports. This is particularly important for Riyadh, with the US becoming a self-sufficient oil exporter, it is necessary to secure other customers.

One could also place Saudi Arabia’s acceptance of China appeasing Iran within the context of a broader geopolitical climate. In the context of major global transformations, the existence of a Chinese alternative to the US—with its very own vision, objectives, and demands—enlarges Riyadh’s chances to better face the economic and security impact of a potential shift in global geopolitics. One could argue that for Saudi Arabia this might be a means to supplement or hedge against US disengagement. Thus, in the long term, China’s strategic balancing of powers in the Persian Gulf might be the steppingstone for a broader engagement.

However, China remains well aware of its limited capabilities when it comes to addressing the region’s obstinate political security issues and has no interest in challenging the US-led regional security architecture. Yet, the recent developments in the Strait of Hormuz force Beijing to consider increasing its security footprint to protect the freedom of navigation that it needs to secure its energy supplies from the region. At the same time, Gulf monarchies are starting to lose confidence in the US security guarantee in the region, based on Washington’s reaction to Iran’s attacks on oil tankers and the attacks on Saudi oil facilities, and its unwillingness to respond to them with force. Saudi Arabia’s cold response to the Soleimani killing could be a further sign of a growing fracture.

This has prompted Riyadh to reach out to China to deepen ties also in the security realm. Beijing seems to be of increasing importance as a security counterpart for the kingdom. The Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and Saudi militaries have conducted joint counter-terrorism exercises in China’s Western province of Xinjiang since October 2016—such exercises Riyadh has traditionally only conducted with the United States. In another show of growing military ties, Chinese navy vessels have visited Jeddah port in the context of an anti-piracy maneuver in the Gulf of Aden in November 2019—only one month before the Iran-Russia-China trilateral exercise—to hold joint drills at the King Faisal Naval Base. Arms exports and technology transfer are another future area of cooperation. While the US is not willing to sell armed UAVs to Saudi Arabia, China has stepped in over the US ban, to build a manufacturing plant for CH-4 UAV drones, similar to the American MQ-1 Predator, in the kingdom. Saudi has also purchased the Wing Loong model, as have the UAE and Pakistan. Although in the long-term, China is not able to fill the US arms sales gap for Saudi Arabia, Beijing’s support in the military realm fits well into the Saudi strategy to build a military industry, and support the theory that Riyadh is willing to turn to China as an alternative where the US is unwilling or unable to step in.

It is still unclear what will be the impact of the killing of Soleimani on Sino-Iranian and Sino-Saudi relations. What appears clearer, however, is that the primary concern for Beijing remains the possibility of a full-scale escalation in the Persian Gulf. In fact, the current tensions between Washington and Tehran have been a major stress test for China’s Persian Gulf strategy. However, Beijing has responded by relaunching its multilateral approach. On the one hand, appeasing Iran to hedge against the US and its allies—as most of China’s other oil suppliers in the Gulf are allies of the US. On the other hand, China strategically engages with Saudi Arabia and other Gulf monarchies and thereby hedges against possible risks that might arise from policies that are more confrontational in the future. Thereby it pursues a two-tiered hedging strategy, balancing against political risks that might arise from an alienation from either side—thus far, successfully. Gulf monarchies have indeed accepted China’s position towards Iran primarily because of the growing economic interdependence, but also due to the necessity of seeking alternative security partnerships. This is particularly true for Saudi Arabia, which needs China to hedge strategically against the declining Western oil consumption, the shrinking security role of the US in the region and the Western discomfort with authoritarian structures within the kingdom.

Julia Gurol is a research associate at the Center for Applied Research in Partnership with the Orient (CARPO). She is also a lecturer at the University of Freiburg. Follow her on Twitter: @JuliaGurol.

Jacopo Scita is a H.H. Sheikh Nasser al-Mohammad al-Sabah doctoral fellow at Durham University. Follow him on Twitter: @jacoposcita.

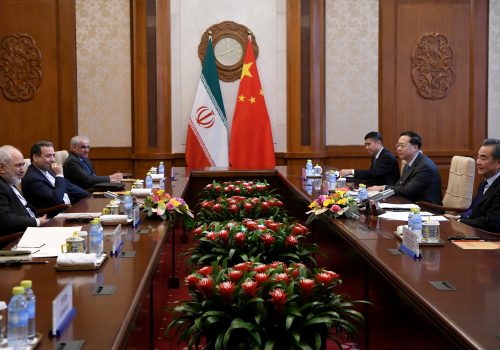

Image: China's President Xi Jinping after a welcoming ceremony for Saudi Arabia's crown prince (Reuters)