Do China and Russia want to replace the US as mediators in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict?

This article is part of a strategic collaboration launched by the Atlantic Council (Washington, DC), the Emirates Policy Center (Abu Dhabi), and the Institute for National Security Studies (Tel Aviv). The authors are associated with the initiative’s Working Group on Chinese and Russian Power Projection in the Middle East. The views expressed by the authors are theirs and not their institutions’.

Do Russia or China have enough influence and interest to make a difference in fostering a negotiated settlement between the Israelis and Palestinians?

The re-emergence of violent conflict between Israelis and Palestinians over the past few weeks has once again trained the eyes of the world on the need to foster a peaceful negotiating process. In this brief reaction piece, three experts from our working group on Chinese and Russian power projection in the Middle East offer their views on the viability of Russia or China bringing the parties closer to the negotiating table.

China recently volunteered itself as an alternative for hosting informal talks between Israelis and Palestinians in Beijing. Although the Palestinian Authority welcomed it, the effort has yet to bear fruit. Meanwhile, on May 5, Russia’s Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov reiterated Moscow’s support for talks to resolve key issues and activate the political process with the help of the Quartet (Russia, the United States, European Union, and United Nations (UN)).

After having developed a four-point peace plan between Israel and Palestine, it is to be seen if China would use its UN Security Council (UNSC) presidency in May and beyond to revive this plan. The UNSC meeting to address the conflict, which was requested by China, Tunisia, and Norway and initially planned for May 14—but delayed by the US to May 16—saw China embrace a more active leading role by chairing the UN Security Council meeting and bashing the US for the Council’s lack of action.

While the consensus among most observers is that Russian and Chinese influence on any new peace process will be minimal, it is worth considering whether Moscow and Beijing may consider US inaction on the issue—or the seemingly “slow” US response—and its general inclination to focus on other parts of the world (or domestically) as an opportunity to exert greater influence on bringing about a negotiated settlement.

A US historical note on the Russian and Chinese role

Since the Madrid peace conference in 1991, the US has acted to ensure that Russia and China play a limited role in negotiations between Israel and its neighbors. The US and Israel were committed in 1991 to the principle of voluntary bilateral negotiations between Israel and Syria, Jordan, and the Palestinians, respectively, and did not wish to “internationalize” these negotiations in the UN or elsewhere. Nonetheless, it was important for the Russians and, to a lesser extent, the Chinese, to be seen as supporters and facilitators of the peace process.

For example, the invitations to the 1991 Madrid conference were issued jointly by the US and Russia, but the Russian role was largely symbolic, with the James Baker-led State Department taking the lead in organizing the Madrid conference and ensuring the parties showed up for it. The Russians also joined the US in co-chairing the Multilateral Peace Process that was initiated at a Moscow meeting in early 1992. This was an early attempt at normalization of ties between Israel and Arab states, bringing together diplomats and experts from thirty or so countries, including Israelis, Jordanians, Palestinians, and other Arab states. They held regular meetings and initiated modest cooperative projects in five areas: water resources, refugees, arms control, environment, and regional security. The Russians co-chaired the Steering Group for this Multilateral Peace Process along with the US and the Chinese hosted several meetings of the functional working groups.

The main objective of this multilateral effort was to demonstrate to Israelis that there was a prospect for good relations with Arab states should they make progress on bilateral negotiations. However, they also served to involve powers such as Russia, China, and the EU in the peace process, while blocking them from getting involved in the bilateral talks between Israel and its neighbors. The multilateral process became the victim of a lack of progress in the bilateral negotiations, and violence between Palestinians and Israelis had all but disappeared by 1996, partially replaced by Middle East Economic Summits and proposals for a Middle East development bank. All these efforts fell victim to lack of significant progress toward Israeli-Palestinian peace and reconciliation—a lesson learned again over the last few weeks.

Richard LeBaron is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council and was chair of the Multilateral Steering Group and the Water Resources Working Group of the Madrid Multilateral Peace Process. Follow him on Twitter: @RBLeBaron.

The Arab perspective vis-à-vis China

China does not have enough influence on the Israeli and Palestinian sides to get them to negotiate a settlement. China has not been a big player in this issue and does not enjoy strong leverage to influence both parties to resolve their conflict. This is why China has not been serious in its efforts to get itself involved. China understands its limitations, so it keeps itself not intimately involved or limits its involvement to a collective international effort.

China’s lack of creativity to deal with this issue and its approach to providing support for generally recognized principles, such as its four-point peace plan presented by president Xi Jinping in July 2017, is a testament to China’s lack of desire and capability to bring about a new settlement between the Israelis and the Palestinians on its own. The plan included: advancement of the “political settlement on the basis of the two-state solution;” upholding a “common, comprehensive, cooperative and sustainable security concept; further coordinating “efforts of the international community” and strengthening the “concerted efforts for peace;” and comprehensively implementing “measures” and promoting “peace with development.” The plan did not include new ideas and did not reflect Chinese willingness to invest resources in the resolution of the conflict. Even appointing a special envoy of the Chinese government on the Middle East issue to facilitate the Arab-Israel peace process has been a symbolic move that has not changed the conflict’s dynamics.

China does, however, have an interest in being seen as fostering a negotiated settlement between the Israeli and Palestinians. But its actions are designed to make itself be looked at as a responsible great power that shares the burden of international stability. This explains why China gets involved in the negotiation process in many international issues even though it cannot influence the parties—for example its participation in the Iran nuclear talks and the Berlin Conference on Yemen. China must be at the negotiating table, as this is part of China’s foreign policy strategy to be recognized as a major party in efforts to resolve international disputes. Therefore, China prefers to be involved in a collective international effort rather than taking the option of going alone for two reasons. First, China does not have the capabilities to be successful by going alone, particularly in this issue where the US is the leading mediator. China cannot challenge the US capability on this issue. Second, China does not want to bear the responsibility as a guarantor of certain negotiated outcomes.

Dr. Mohamed Bin Huwaidin is an associate professor of Political Science at the United Arab Emirates University.

The Israeli perspective vis-à-vis Russia

Russia has stepped up its diplomatic activity in response to the current escalation between Israel and the Palestinians. Its public statements are characterized by equidistance from the two belligerent sides and calls for defusing the situation and resuming the negotiations under the auspices of the Quartet—which aims for a “two-state solution.”

Russia was consistent in the years of the Donald Trump administration in criticizing Washington’s approach to marginalizing the Palestinian problem. It called for renewed Israeli-Palestinian negotiations, suggested Moscow as a meeting place, and tried to bring unity between the Palestinian factions by keeping open communication channels with the Palestinian Authority and Hamas. Russia reacted with skepticism to the Abraham Accords and claimed that, despite being a positive development, it could not circumvent the solution to the Palestinian question—considered one of the core destabilizing problems of the Middle East. Moscow instead called to convene a Middle East Peace Process ministerial-level conference with the Quartet, Egypt, Jordan, United Arab Emirates (UAE), Bahrain, the Israelis, and the Palestinians. In Russia’s eyes, the present crisis proves they were right, as the Palestinian problem is again high on the agenda of the region and the international community.

While Russia is the only major international actor able to communicate directly with all the sides and factions, Moscow lacks the levers to pressure Israel or the Palestinians to change their positions. Therefore, its proactive multilateral diplomacy is meant to prove to the West that it is a responsible global power. The Israeli-Palestinian problem widens the shortlist of international issues that provide common ground for Russia and Western capitals. The Russians are content that the crisis reinvigorated the Quartet envoys’ meetings and that the UNSC will deal with the situation.

Behind the scenes, the Russians are quite pessimistic about the possibility of moving Israeli-Palestinian reconciliation forward. In recent months I have witnessed a growing group of senior Russian Middle East experts probing the “track-2” channels and seeking ideas to promote peacebuilding through a small-steps-strategy of regional cooperation on economic and environmental issues. They hope that solving concrete problems will build confidence for dealing with bigger problems. This approach is not embraced yet as Moscow’s official position.

Lt. Col. (ret.) Daniel Rakov is a research fellow at the Institute for National Security Studies in Tel Aviv, focusing mainly on Russian Policy in the Middle East and Great Power Competition in the region.

Beijing’s latest messaging around Jerusalem

During his March 2021 Middle East visit, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi offered China’s services as a mediator between Israel and Palestine, but there has been no public mention of this initiative since then. With the eruption of violence in Jerusalem, Zhang Jun, China’s representative to the United Nations and current president of the UNSC, issued a statement on May 10in which he condemned violence against civilians, called for restraint from both sides, and encouraged de-escalation.

This is consistent with China’s approach to Israel-Palestine affairs. Politically and ideologically, it leans towards the Palestinians and always has since the days of Mao, when Third World solidarity was a feature of its foreign policy. Economically, however, it leans heavily towards Israel. This makes for a tough—and not always credible—balancing act. Beijing is consistent in its messaging but its engagement on the issue remains tepid.

When it comes to Middle East conflict, China typically calls for regional actors to resolve their own problems, calls for external actors—e.g. the US—to not interfere, and offers support. It is action for appearance’s sake, but the reality is that Beijing’s influence to solve political disputes remains limited. In this case, the regional environment is challenging to navigate, with warming ties between Israel and the UAE, Bahrain, Morocco, and Sudan adding to an already challenging situation. It is unlikely that Chinese leaders would want to wade into this beyond working within the framework of the UN and cooperating with Middle East partners.

Nevertheless, Beijing will benefit from the widespread regional frustration stemming from the US’ unswerving support for Israel, especially coming at a time when the US is criticizing China for human rights abuse in Xinjiang province.

Dr. Jonathan Fulton is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council. He is also an assistant professor of political science at Zayed University in Abu Dhabi. Follow him on Twitter: @jonathandfulton.

Conclusion

The perspectives presented above signal that neither China nor Russia have the capabilities or see it in their interest to move forward as leading intervening powers to address this longstanding conflict. Both rely heavily on rhetorical support, often in the UN framework. Beijing and Moscow are aware of their constraints. China’s leverage to influence both Israelis and Palestinians is limited and, despite Russia’s ability to communicate with all sides, it lacks the levers to pressure either Israel or the Palestinians to change their positions. China and Russia would not even consider being seen as the lone guarantors of a resolution and don’t want to be viewed as failing should they try to play a bigger role.

As noted, Russia is content that the latest events have renovated the Quartet’s format and role to end the conflict, thus somewhat restoring Moscow’s equal status to the US, EU, and UN. Meanwhile, amid the recent violence, Beijing and Moscow will likely see some benefit in the ongoing disappointment directed towards the US and the somewhat indirect role it is playing. For China, this Middle East crisis may divert some of the international attention focused on its treatment of the Uyghur population in Xinjiang. Beijing and Moscow recognize that the US remains the only power with considerable leverage over Israel, even while likely assessing that, at this point, Washington will make no serious move to bring the parties closer to a negotiated settlement, and limit its efforts to attempt to mitigate the damage.

Joze Pelayo organized this article and authored the introduction and conclusion. Joze is a program assistant at the Scowcroft Middle East Security Initiative/Middle East Programs. Follow him on Twitter: @jozemrpelayo.

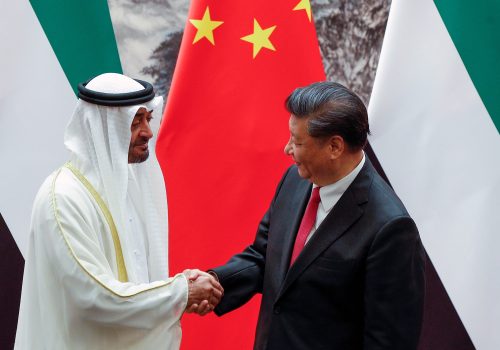

Image: Russian President Vladimir Putin attends a meeting with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu at the Bocharov Ruchei state residence in Sochi, Russia September 12, 2019. REUTERS/Shamil Zhumatov