Here’s how Amman can boost women’s workforce participation

Unemployment is a dire problem in Amman, Jordan’s capital and largest financial center. Like much of the rest of the world, Jordan must climb out of an economic pit exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic; Jordan’s unemployment rate was 23 percent in the second quarter of 2020 (up from 19.3 percent in the first quarter of 2020). One key to promoting long-term economic growth is achieving greater female labor force participation. According to the World Bank, Jordan has “the lowest female labor force participation of a country not at war.” This article will focus on the situation in Amman, recognizing that, while some of the findings may apply to the country as a whole, various factors may also be impacting Jordan’s other cities and the rural areas in particular.

The reasons for Amman’s low female labor force participation rate can be grouped under the following categories: structure, norms, and laws in the labor markets; perception of women and their role in society; and childcare and transportation infrastructure.

Overview of Amman’s female labor force participation

Amman’s female labor force participation rate in 2020 was estimated at 17.1 percent compared to 22 percent in Egypt, 31.4 percent in Saudi Arabia, and 52 percent in the United Arab Emirates. The global average was 47.3 percent in 2019.

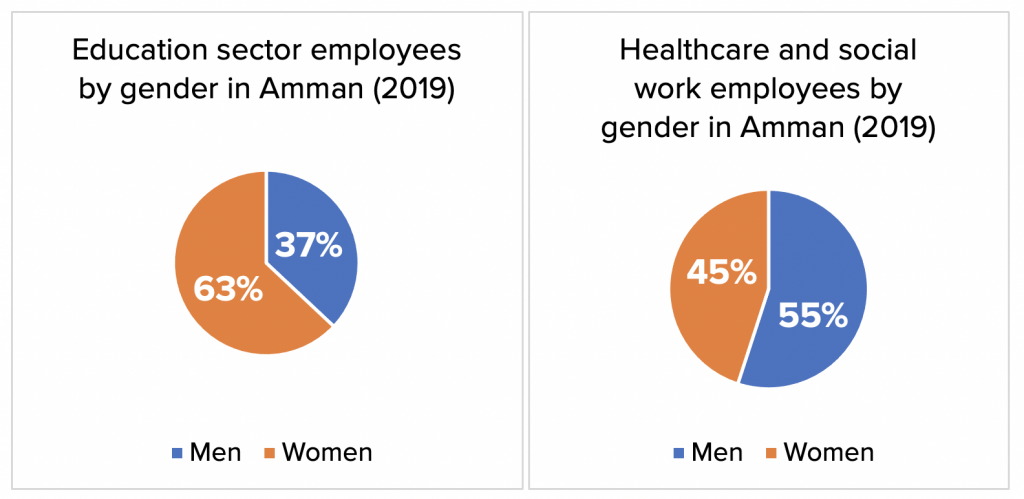

This situation is “shocking,” says Jordanian Nour Al Hassan, founder and CEO of translation company Tarjama, because women in Amman are highly educated and are seeking advanced degrees at higher rates than men. Al Hassan explains that Jordan “appears more modern than it actually is, but, in reality, the laws do not support women working. Flexible hours are an issue and on top of that you have cultural barriers.” The only woman-dominated sector in Amman is education, which had 63 percent women workers in 2019 according to Jordan’s Department of Statistics.

Men dominated all the other sectors, with the exception of healthcare/social work, which had 45 percent women workers in 2019. This is not surprising, since worldwide women continue to be overrepresented in education and healthcare sectors.

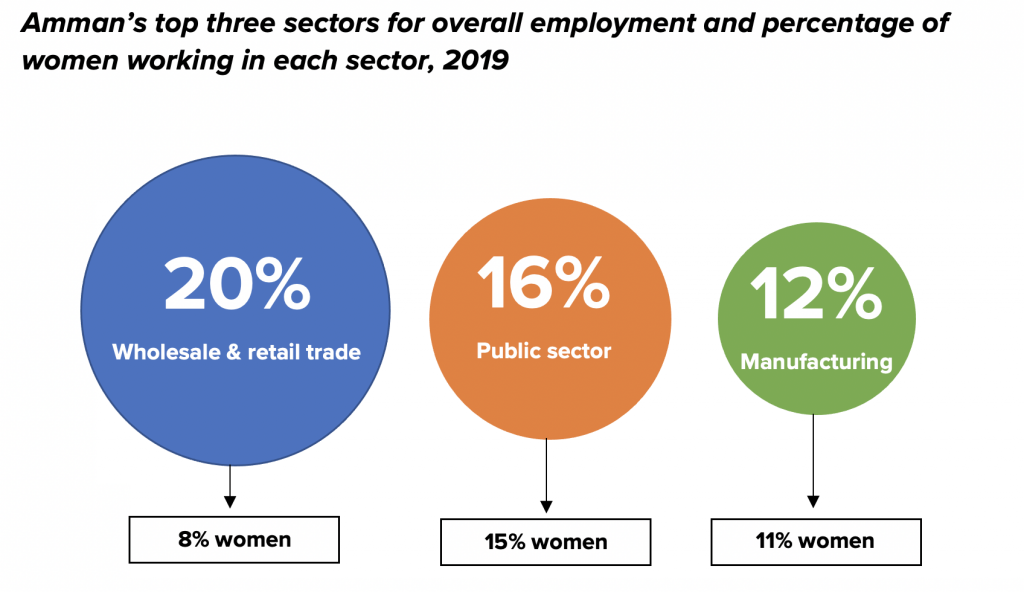

Compared to the percentage of women in the education and healthcare/social work sectors, the rate of female labor force participation in the largest sectors in Amman—wholesale and retail trade, the public sector, and manufacturing—is quite low. In short, women are extremely underrepresented in the sectors that together make up nearly 50 percent of Amman’s jobs.

Still, statistics about formal employment do not capture the significant informal economic activity in Amman, which includes everything from small online businesses to gig workers. Indeed, it is estimated that over half of all employment in Jordan is informal.

Women are increasingly utilizing new technologies and online platforms to sell handmade goods and offer their knowledge services from home via companies such as Tarjama. This trend will surely buoy women’s labor force participation, but as gender and development scholar Allison Anderson notes, “access to and use of information and communications technology (ICTs) is not in and of itself sufficient to overcome the numerous obstacles to women’s economic participation.” Women still need childcare infrastructure, societal and family support, and viable career paths to unlock the full benefits of ICT. Still, the current female labor force participation rates in Amman do not tell the full story and more accurate data about informal employment rates of women is needed.

Structure, norms, and laws in the labor markets that impact female labor force participation

Micro enterprises with five employees or less make up the overwhelming majority—an estimated 89 percent—of all private enterprises, which presents challenges. As Endeavor Jordan Managing Director Reem Goussous explains: “the majority of conservative families don’t want to have their daughters or wives working in a small setup where interaction is mostly with males, and working hours are long. This is not viewed as safe or culturally acceptable. This is why we see the larger and more established corporations such as banks have a disproportionately larger representation of women.” The number of medium, large, and small enterprises in Jordan is far lower than the number of micro enterprises, further limiting employment options for women.

Concerns about women’s safety in workplaces—and protecting women’s reputations—also stem from the lack of adequate legal protection against workplace sexual harassment and assault. According to JoWomenomics CEO and Co-Founder Mayyada Abu Jaber, “The current labor law actually mentions sexual assault, not harassment. Under the law, people who are sexually assaulted at work have the right to leave their job and get severance pay, but that is the extent of their options unless they want to pursue a criminal law claim, which could become a family issue and could lead to violent retribution.” The law does not stipulate a penalty for perpetrators of sexual assault.

Thus, if sexual assault or harassment occurs, there is not a mechanism to report abuse, protect one’s job, and ensure the harasser pays a price and is deterred from future offenses. “While the law says that the government can close a business if multiple violations are reported,” adds Abu Jaber, “that step does not address the problem and is in fact harmful to the economy.”

The legal barriers to women’s financial independence also prevent many women from pursuing a career. As Secretary-General of the Jordanian National Commission for Women Salma Nims puts it: “What we need is women’s economic autonomy, not just economic participation.” Because the legal system is biased towards the idea of the husband as the breadwinner, women who work and contribute towards household expenses and joint assets may pay a financial price for working and may not be awarded their fair share if a marriage ends. If women cannot achieve economic security and independence or enjoy some financial benefits from working at minimum, many will stay out of the workforce.

Perception of women and their role in society

Perhaps the most challenging issue that must be surmounted is attitudes about women. These attitudes are changing but are still a long way from accepting equity.

As Jordanian CEO of BizWorldUAE.org Helen Al Uzaizi describes, “Even if you have a strong family support network, the expectation of you as a woman is that you stay home or take on a job with a less demanding role. The university degrees women get have nothing to do with market needs. It’s just another checkmark to make them more attractive for marriage.”

This anecdotal evidence is supported by data. In the 2020 Arab Youth Survey, 73 percent of young Arab men and 70 percent of young Arab women said that they think women should work part-time or not at all. These attitudes are by no means found only in the Middle East. A 2019 Pew Research Center survey found that 76 percent of American adults think it is ideal for a father to work full-time, yet only 33 percent of American adults think it is ideal for a mother to work full-time.

Aside from the problematic stereotypes about women being “better” at caregiving and managing a household that these poll results underscore, these views are not in touch with reality. Working part-time is not feasible in many professions and it makes financial independence or rising to a senior role far less likely.

Childcare and transportation infrastructure

Women in Amman are primarily working in “traditional” professions such as teaching and healthcare. It can be difficult to enter these jobs if they have family care responsibilities or if the pay would not compensate for the childcare and transportation challenges the worker might then have to navigate.

Amman currently does not have enough affordable childcare options for families or safe, reliable, and affordable transportation for workers, creating additional roadblocks for women who want to work.

As Atlantic Council Middle East Initiatives & Rafik Hariri Center Deputy Director and Jordanian-American Tuqa Nusairat argues: “Jordan’s safety nets allow most families to get by, so many women don’t feel the burden of providing financially for their families as compared to similar economies in the region. The barriers for working women are high, and the financial return at the moment is too low.”

Recommended policy actions

To raise female labor force participation in Amman, the United States, international organizations, and Jordan’s government and activists should prioritize five areas:

- Expand childcare infrastructure: Recent laws in Jordan mandated creating on-site daycare for companies that have women employees with a combined total of fifteen or more children under the age of five and alternative arrangements for workplaces with a lower number of children. However, adoption is incomplete and there are concerns that this mandate may cause companies to cap the number of female employees to avoid triggering daycare responsibilities. Childcare that receives public funding and is not tied to a company having a certain number of female employees would be a better solution.

- Legal changes to prevent and respond to sexual harassment and assault: Activists such as Salma Nims, Secretary-General of the Jordanian National Commission for Women, have been working to address the current inadequate legal protections against sexual harassment in the workplace. Nims spearheaded public awareness campaigns in partnership with faith-based organizations and human rights groups to educate Jordanians in university, school, and workplace settings about what sexual harassment entails. According to Nims, this led the Labor Ministry to make changes that require new companies with ten or more employees to have a sexual harassment and violence policy.

In June 2020, a campaign led by the International Labor Organization and United Nations Women raised awareness about this issue and pushed the Jordanian government to adopt more wide-ranging legislative changes. The country’s parliament is now considering amendments to the labor law’s sexual assault article. If these amendments pass, they will “define sexual harassment and offer employees more protection,” says Nims. However, she adds that “the social stigma in Jordan attached to reporting harassment along with the legal procedures required to prove an offense occurred will still pose challenges to addressing this issue.” - Public transportation: Affordable, safe, and reliable public transit options are a must to enable women (and all workers) to get to work. Amman does not have a metro system and, while there are buses, their routes and timing are not sufficient for most commuters. Better public transportation options are needed to boost overall employment.

- Continued expansion of part-time, flexible, and remote work: One key to recruiting and retaining women is flexibility in terms of when and where work is performed in sectors where this is possible. Women all over the world face the burdens of the “second shift” (childcare, cooking, and cleaning) and “emotional labor” (e.g. managing a household). A silver lining of the COVID-19 pandemic is that many workplaces were forced into fully remote operations. This experience—which has proved to skeptics that remote work is both possible and productive—may prove helpful to women’s labor force participation in the long run. The gig economy, enabled by new technologies, is also expanding in Amman and offers new opportunities for women to use Ureed.com and other platforms for freelance work.

In May 2019, Jordan amended its labor law to permit flexible and part-time work. Flexible work is a positive step, but it is not a panacea since not every job can be done remotely. Furthermore, as JoWomenomics CEO and Co-Founder Mayyada Abu Jaber puts it: “For many women, leaving the home to work gives them a sense of agency and helps them find themselves. Working from home can be smart if we do it smartly, but if we don’t, it could just add to women’s burdens by making them continue their childcare and housework while also doing paid work. Then they may just end up resigning.” - Role models, mentoring, and networking support: Women and men need to see more positive examples of women succeeding professionally. Women will benefit from connecting with working women and male allies who can help them market themselves for jobs, discover employment opportunities, and provide emotional support along the way. Success stories and support networks will also help shift problematic attitudes about women over time as more women are able to enter and stay in the labor force. Additionally, this will help bring about additional legislative changes that are needed in terms of sexual harassment protection and recognizing working women’s financial contributions to families and more.

Stefanie Hausheer Ali is deputy director of the Atlantic Council’s empowerME initiative at the Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East.

empowerME at the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East is shaping solutions to empower entrepreneurs, women, and the private sector and building influential coalitions to drive regional economic integration, prosperity, and job creation.

Image: Jordanian women from the civil defence department attend a training class at the civil defence center in Zarqa city, 25 km (16 miles) east of Amman January 27, 2010. Since 2007, the Jordanian civil defence started working to integrate the female component of its work within the official crew. So far, 81 women have graduated in first aid from the Faculty of Civil Defence. REUTERS/Muhammad Hamed