The fall of the Assad regime is just the beginning of Syria’s quest for stability

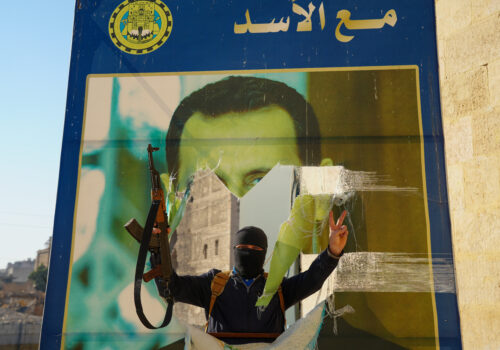

After the sudden exit of ousted Syrian leader Bashar al-Assad, the only certainty is that both the former Islamist opposition, led by al-Qaeda offshoot Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), and the Syrian people face a monumental transition. This is not so much the beginning of the end of the bloody civil war. Rather, it is the end of the beginning of the conflict, as Syria—freed from Assad—attempts to find its way despite significant social and religious divisions and the presence of many armed groups.

After gaining its independence from restrictive and authoritarian French rule, Syria suffered through a series of short-lived and unstable regimes, endured more than fifty years of brutal Assad family rule, and finally devolved into civil war. Syria is divided by competing ethnic and sectarian communities, creating barriers to the coalition building that could foster greater stability outside authoritarian rule. If, however, an Islamist coalition led by HTS can consolidate power in this environment, it would represent a massive transformation in a nation that has long been cursed with instability and portend significant implications for the region.

Broken promises and a divided nation

The Syrian Arab Republic, as it exists today, is largely based on territorial boundaries established during the French mandate, which lasted from 1920 to 1946. The British and French—anticipating an Ottoman defeat in World War I and eager to absorb the spoils into their respective colonial empires—divided Syria between them: a French northern Syria and a British southern Syria, breaking wartime promises to the Arabs to promote their independence if they revolted against Ottoman rule during the war. France further subdivided its area, managing Lebanon—with much of northern Syria’s Mediterranean coastline—as a separate mandate and ceding another portion of the coast around the city of Iskenderun to the newly independent Republic of Turkey.

SIGN UP FOR THIS WEEK IN THE MIDEAST NEWSLETTER

The borders drawn by the European powers before and during the Syria mandate not only divided ethnic and sectarian communities but also institutionalized and exacerbated existing divisions. The Sunni majority, which makes up more than two-thirds of the state’s population, was composed of multiple ethnicities including Arabs, Kurds, Turkmen, and others. A third of the country’s population was composed of Christians, Shia, and Alawi Muslims, as well as smaller Druze and Jewish communities, among others.

Further, the Arab centers of culture, learning, and nationalist ferment—cities such as Beirut, Damascus, and Baghdad—all ended up in different countries. The artificial boundaries ignored historical, cultural, and social ties, setting the stage for many of the conflicts and identity struggles that have continued to shape the region in the present era.

France did little to build the state institutions necessary for the constricted Syrian republic to manage its affairs after gaining independence in 1946. The new state went on to have twenty-one governments in the following twenty-four years, when Hafez al-Assad assumed power in an intra-regime coup in 1970.

Decades of suppression

Although Hafez introduced a level of stability previously unknown in Syria, he established one of the most authoritarian states in the region. His minority regime—dominated by the schismatic Alawi sect of Islam—severely circumscribed the role of Sunni Muslims, which comprised most of Syria’s population, in politics and the security services. A 1982 challenge by the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood was met with brutal crackdowns, which resulted in an estimated tens of thousands killed and forced the organization into exile.

The elder Assad’s suppression of the Muslim Brotherhood set the script for his son Bashar al-Assad’s later effort to quash the demonstrations that began the 2011 Syrian uprising: declaring all opposition elements to be Islamic extremists and mobilizing state security resources to destroy them. Although radical Islamists, including al-Qaeda elements and the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) would ultimately conduct their own struggles against the regime, the initial popular uprising was not ideological, and it was Assad’s overreaction that turned it into a civil conflict that would engulf the entire country.

It was Hafez’s effort to protect the Alawis from a vengeful communal reorganization after his death that led him to install his son in the presidency. Notably, Bashar was not Hafez’s first choice for succession. Years of preparing his oldest son Basil came to naught when he was killed in a car accident, putting the ophthalmologist Bashar in line to assume the presidency upon Hafez’s death in 2000. Despite talk of political and economic liberalization, the younger Assad’s regime was ruthless and kleptocratic. It was that ruthlessness that would ultimately lead to demonstrations, civil war, and the regime’s undoing. The Assad government’s brutal crackdown against children who had painted anti-regime graffiti in 2011 in the southern city of Daraa, who were subjected to torture and abuse, was one of the incidents of oppression that sparked the almost fourteen-year civil war that would ultimately result in Assad’s ouster.

Russia, Iran, and the Lebanese militant group Hezbollah had fought on behalf of the regime earlier in the war. But when HTS launched its offensive in November, each of these allies couldn’t respond fast enough, as they had all been weakened by other conflicts and had fewer resources to dedicate to the Assad regime. Bashar and his family are now living in asylum in Russia, as Moscow negotiates with HTS to retain its military bases in Syria.

International implications

Whether the Islamist coalition led by HTS can consolidate power over the country has significant regional implications. If it does, Tehran will have lost a stalwart ally and a link in its land bridge to Lebanon’s Shia community. The elder Assad, contemptuous of former Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein, had gone so far as to support Iran in the 1980–1988 Iran-Iraq war, and Syria could always be relied upon to support Iranian regional policies. With a Syrian government no longer friendly toward Iran, Tehran’s ability to support Hezbollah would become far more complicated.

Israel, which has attacked Syria for being a conduit of Iranian support to Hezbollah in Lebanon, may find that radical Sunni Islamists are just as dangerous and just as committed to Israel’s destruction as Hezbollah’s Shia. Both Israel’s respective borders with Lebanon and Syria are each approximately fifty miles long, but there is no United Nations (UN) Security Council resolution, however poorly executed, mandating a buffer zone along the border area in Syria as UN Security Council Resolution 1701 does in Lebanon. Finally, it is worth remembering that only the United States recognizes Israeli sovereignty over the Golan Heights, which is internationally recognized as Syrian territory captured in the Arab-Israeli war in 1967. In fact, UN Security Council Resolution 497 explicitly states that Israel’s “decision to impose its laws, jurisdiction, and administration in the occupied Syrian Golan Heights is null and void and without international legal effect.”

Turkey, under the regime of the Islamist Justice and Development Party of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, known to have close ties to global Islamist establishments, would presumably benefit from a relationship with the new regime, as it has long supported elements of the Syrian opposition and demonstrated long-standing disquiet about Assad remaining in power. Ankara will seek to remain involved in Syria to repatriate the millions of Syrian refugees it currently hosts and to combat the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG), an organization it considers a dangerous terrorist group because of its links to the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), which is designated as a terrorist organization by both Turkey and the United States.

The United States’ principal Arab partners—Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates—have all taken hostile stands against Islamists since the Arab Spring uprisings of 2010-11, and the new Syrian regime may struggle to gain acceptance or support from other Arab states. Qatar, however, has often been accused of supporting Islamist groups considered beyond the pale by its Arab neighbors, and Doha may see an opportunity to make its mark on the region by buttressing the new HTS-led regime.

Minority rights

While it would be inaccurate to assert that the Syrian Arab Republic, as carved by European colonial powers, never had a chance at stability, both European rulers and Syrian leaders share great responsibility for the mess in which the country finds itself. Neither contributed to the evolution of functioning institutions that are essential for stability. Without a new national identity in the constricted Syrian republic, ineffectual Sunni Arab-dominated governments and communal tensions combined to promote instability and, ultimately, a strongman dictatorship in the form of Alawi minority rule.

Now, in the aftermath of Assad’s ouster, both internal divisions among Syrians and external interests in shaping the country’s future threaten to render the current moment a lull in the civil war rather than its conclusion. Although the emerging HTS-dominated government has yet to consolidate its authority, it would be highly unexpected if—as a Sunni Islamist government—it were to guarantee the civil rights of Twelver Shias, Alawis, Druze, and other groups generally considered schismatic and which are often discriminated against among Sunni-majority communities.

There are many flavors of Islamists in Syria, both within and outside the HTS coalition, including pockets of ISIS. Elements of the Syrian military may yet reinvent themselves into an insurgency, as happened next door in Iraq after the fall of Hussein’s Baathist regime in 2003. Minorities, particularly Alawis, may elect to fight to protect their future from perceived Sunni animus. Syrian Kurds, long disenfranchised by the outgoing regime, are armed and have demonstrated resilience against other armed groups.

Finally, although the United States is mostly steering clear of direct involvement in Syria’s transition, Russia, Iran, and Turkey all have major interests in attempting to shape the country’s trajectory in their favor.

Given Syria’s long history of sectarian divisions, the presence of multiple armed factions in the country, and external powers’ competing interests in shaping the aftermath of the Assad regime’s downfall, the swift triumph of HTS and its allies may prove to be merely the end of a phase of the Syrian civil war rather than the end of the conflict.

Amir Asmar is an adjunct professor of Middle East issues at the National Intelligence University. He was previously a senior executive and Middle East and terrorism analyst in the US Department of Defense.

The views expressed are the author’s and do not imply endorsement from the Office of the Director of National Intelligence or any other US Government agency.

Further reading

Wed, Dec 18, 2024

Will Russia be able to keep its bases in Syria?

MENASource By Mark N. Katz

It would be in the United States’ and Israel’s interests not to give the new Syrian government reasons to let Russia keep those bases.

Thu, Dec 5, 2024

What does Turkey gain from the rebel offensive in Syria?

MENASource By Ömer Özkizilcik

The rebel offensive took many by surprise, but analysts familiar with the situation in Syria were aware that the rebels were prepared to launch it by mid-October.

Tue, Dec 17, 2024

Dispatch from Damascus: Celebrations and concerns as a new Syria takes shape

New Atlanticist By Ömer Özkizilcik

Syrians in Damascus are celebrating the fall of the Assad regime, but that joy is mixed with concern for how the country’s new leaders will govern.

Image: U.N. Syria envoy Geir Pedersen meets with head of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham and Syria's de facto leader, Ahmed al-Sharaa, also known as Abu Mohammed al-Golani in Damascus, Syria in this handout released on December 15, 2024. Hayat Tahrir Al-Sham/Handout via REUTERS THIS IMAGE HAS BEEN SUPPLIED BY A THIRD PARTY. NO RESALES. NO ARCHIVES. TPX IMAGES OF THE DAY