The Ukraine crisis is a reminder of why conflict-driven carbon emissions matter in MENA and beyond

As the world witnesses the shocking humanitarian disaster unfold in Ukraine due to Russian aggression, there is much concern about President Vladimir Putin attacking Ukraine with unconventional weapons. In addition to the dire, direct human cost of the conflict, its impact on climate change should be very concerning, as burning fuel tanks or damaged gas pipelines emit increased carbon emissions into the atmosphere.

Such attacks impact not only the region in which the damage occurs, but also globally. This is augmented when countries dependent on Russian gas respond to the invasion by increasing their use of polluting fuels instead of acting to curb them.

At a time when humans are racing against the clock to prevent irreparable damage to the planet over the next one to two decades, contending with conflict-driven carbon emissions on top of already massive human-sourced emissions is unbearable.

Much has been written on the impacts of climate change on conflicts in general. However, what needs to be noted is how current conflicts contribute to climate change.

In the past, bombing energy infrastructure meant impacting the energy supply of a country. Now, it’s better understood that the polluting impacts of bombing a fuel supply don’t distinguish between political borders.

Unfortunately, the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) is vulnerable to climate change-driven conflict,such as battles over water sources in the context of increased droughts, due to the much higher pace of global warming in the region compared to the global average. The Middle East, however, is also vulnerable to and responsible for existing conflicts in the region that contribute to increased regional and global carbon emissions. For example, the images of burning oil fields in Kuwait during the 1991 Persian Gulf War were shocking, especially when we realize that an estimated 2-3 percent of all global emissions came from the oil wells set ablaze at the time.

Similarly, when Iran attacks Saudi oil facilities in 2019 or a largescale explosion occurs in Beirut’s port in 2020, people—whether in New Hampshire and China’s Shenzhen—should also be concerned about the impact this can have on carbon emissions.

Thankfully, as New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman has pointed out, there are now tools to calculate how much a single event or company causes carbon emissions. As a result, it’s possible to more or less calculate how many carbon emissions have been contributed by the bombing of a power plant or gas pipeline. For example, Planet.com uses satellite imagery “to observe the entire global land mass every twenty-four hours in high resolution in order to make the changes unfolding on the ground ‘visible, accessible and actionable.’”

When the world is fighting an uphill struggle to combat climate change, it simply cannot afford additional man-made, conflict-driven, carbon emission-intensifying disasters, whether in MENA or elsewhere. The international community should consider adopting punitive measures to hold countries accountable for accelerating global warming through acts of war and aggression. This would build on and work parallel with existing humanitarian laws and enforcement measures. The United States and European Union (EU) can lead such an effort via the United Nations, but it’s also important to work closely with China—considering the critical role Beijing can play in curbing global carbon emissions—(whether at home or via the international system), and others, such as India and eventually Russia. This can be either done on a multilateral treaty basis, by individual legislation, or simply by adopting unilateral conflict carbon emissions sanctions.

Work is already being done to assess NATO military contributions to carbon emissions and by others such as the EU, but more work is needed to focus on the climate impacts of direct conflict in the MENA region and beyond to create climate-related legal, financial, and even military disincentives for waging war.

Reducing carbon emissions is increasingly becoming a central national security issue. Countries need to think twice before damaging energy infrastructure; not only in terms of the electricity supply of a targeted country, but also in terms of climate impacts for the planet. The current Ukraine crisis is an alarming reminder that, as senseless wars continue to rage in the twenty-first century, the uphill struggle to combat climate change just got steeper.

Ariel Ezrahi is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Middle East Programs. He is also the Director of Energy at the Office of the Quartet in Jerusalem. Follow him on Twitter: @aezrahi.

Further reading

Thu, Mar 24, 2022

Action must be taken to award reparations to victims of Russian war crimes

MENASource By Jomana Qaddour, Celeste Kmiotek

The international community is overdue for an overhaul of the legal tools accessible to victims of state-sponsored crimes in the twenty-first century. Perhaps justice mechanisms for Ukraine and Syria can stymie such impunity once and for all.

Wed, Feb 23, 2022

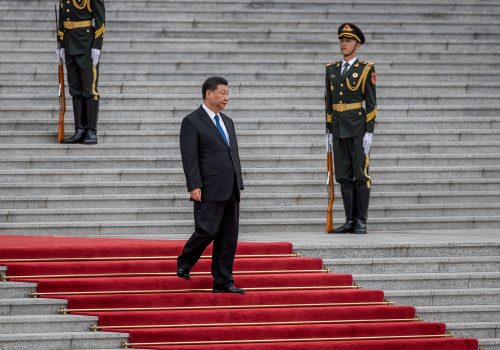

China and Russia are proposing a new authoritarian playbook. MENA leaders are watching closely.

MENASource By Ahmed Aboudouh

It’s on major Western democracies to make democracy appealing again by aggressively filling the gaps China and Russia exploit to make the world more accommodating to their political models and the new trend of rising authoritarianism.

Thu, Feb 17, 2022

Algeria’s fate is tied to the Ukraine crisis. Will a war extinguish hope for the country’s popular movement?

MENASource By Andrew G. Farrand

In light of its recent history, Algeria is one country whose fate could swing substantially based on Russia’s actions in eastern Europe.

Image: View from a building in Kyiv (Kiev). After a Russian Strike, a fire broke out at an oil storage facility in the city of Vasilkov near Ukraine capital early on February 27, 2022, during the Russian Invasion of Ukraine. Photo by Raphael Lafargue/ABACAPRESS.COM