Russia’s war in Ukraine is making Saudi Arabia and the UAE rethink how they deal with US pressure over China

The response of the Gulf Arab states to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has been somewhat revealing of the depth of fissures between the United States and its Gulf allies. The “stress test” United Arab Emirates (UAE) Ambassador to Washington, Yousef Al Otaiba, hinted at on March 3, was on full display in the pushback by the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries—particularly Saudi Arabia and the UAE—against pressure from Washington to condemn the invasion and side with Ukraine.

China may be one country closely examining the dynamics of the interactions between the two sides over Ukraine and the strategic implications that will likely result from them.

For the Chinese Communist Party, the moderately independent position the US’s Arab Gulf allies devised to respond to the bloodiest conflict in Europe, perhaps since World War II, is a culmination of nudging more US allies away from its orbit. China’s ultimate goal is to push more US partners towards establishing strategic neutrality and doesn’t expect them to defy Washington’s interests outright.

After all, the Ukraine crisis affects the Gulf region, despite not imposing a direct threat to its security. The volatility of energy markets, the enormous side effects the Gulf economies were exposed to due to multilateral sanctions on Russia, and their vulnerability to the ramifications of the intensified great power competition—in terms of having to pick sides and unwillingness to observe US interests—all represent systemic pressures Gulf leaders have to grapple with.

How Saudi Arabia and the Emirates reacted

The GCC countries’ response to the conflict in Ukraine has been to call for a political settlement, which reveals a desire to sit on the fence and resist being drawn into the diplomatic saga around it.

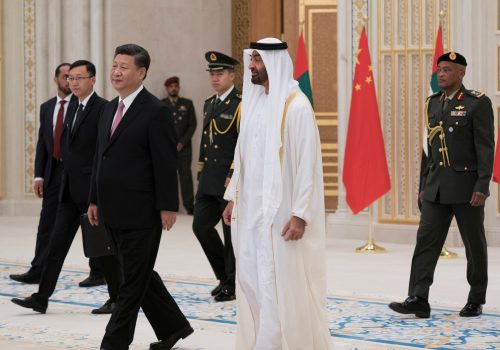

The Saudi and Emirati response, in particular, has been telling. While their de-facto rulers, Crown Prince Mohamed bin Salman (MBS) and Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed (MBZ), reportedly snubbed a call from US President Joe Biden, they both reached out to Russian President Vladimir Putin in early March. And, when Chinese President Xi Jinping called MBS on April 15, the Saudi Crown Prince picked up the phone, conveying to Xi his willingness to sign an agreement to “synergize Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 with the Belt and Road Initiative.”

MBS also resisted the Biden administration’s demands to abandon the OPEC+ mechanism designed by Saudi Arabia and Russia to put a lid on oil output.

The UAE, which has held a seat on the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) since January, has joined China and India in abstaining on a resolution condemning Russia’s invasion on February 25. However, both countries later voted in favor of a United Nations General Assembly resolution on March 3 to denounce the invasion in a bid to cool tensions with the US.

The UAE’s abstention was also possibly derived from its national security considerations. The UAE’s move likely triggered Russia’s abstention in the UNSC resolution that sought to impose an arms embargo on the Iran-backed Houthis in Yemen on February 28, though the two sides deny a deal was made on the voting.

US Secretary of State Antony Blinken tried to calm the relationship jitters during a meeting with MBZ in Morocco on March 29, where he pledged “to do everything [the US] can to help [the UAE] defend [itself] effectively” against Yemen Houthi attacks on both countries.

But the ties between the US and its Gulf allies will most likely remain far from its traditional trajectory over the past decades. And China stands to benefit from the accelerated deterioration of the relations since Ukraine.

The China angle

Chinese leaders may think that Ukraine is a palpable indication of the GCC states’—specifically Riyadh and Abu Dhabi’s—potential reaction to any future conflict over Taiwan’s independence. During his phone conversation with Xi, MBS reaffirmed that Saudi Arabia “firmly adheres to the One-China principle,” which entails recognition of the government of the People’s Republic of China as the only representative of China.

Gulf Arab leaders have invested heavily in their countries’ relations with China and built personal bonds with President Xi. Russia, although to a lesser extent, charted the same course and may perceive the Gulf Arabs’ hesitation to entirely toe the US line over Ukraine as a strategically high return on investment.

Russia’s recently increasing influence in the Gulf region mainly originates from aligned security agendas in Syria and Libya, as Russia was willing to become a stakeholder by deploying conventional forces in Syria and the Wagner mercenaries in both conflicts. This is coupled with Moscow’s eagerness to control oil output through the OPEC+ mechanism with Saudi Arabia.

On the other hand, China has been the largest trade partner with the GCC block since 2020, their biggest oil buyer, and a prominent source of direct investments through its signature Belt and Road initiative. The two sides enjoy a shared vision, supporting opening the region to other powers such as China, Russia, and India and cooperating on maritime security, renewables, and advanced military and telecommunications technologies.

Cooperation in energy trade and Chinese direct investments have become relatively indispensable for the Gulf states’ economic transformation away from fossil fuel energy and a primary source of advanced tech. This level of interconnectivity and economic interdependence has granted China unprecedented political leverage over GCC states.

The forecasted resistance by the Gulf states against potential pressure by the US to adopt policies aligned with its vision in any future conflict with China should not come as a surprise. The two sides have differences in values and a growing divergence of interests.

Many in Washington are concerned about China’s active bid to make inroads into the Gulf’s security sphere. They cite the alleged building of a military facility in an Abu Dhabi port and satellite images of what was thought to be a site for manufacturing ballistic missiles in Saudi Arabia.

Chinese telecommunication giant Huawei has been a significant source of contention in the US. The Biden administration voiced its concerns to the GCC states over the company’s 5G networks and its impact on Washington’s security and defense ties with the region.

In addition, while the Biden administration continued President Donald Trump’s lambasting of China over its treatment of the Uyghur Muslim minority, Gulf leaders and the majority of Middle East elites generally repeated their support for China’s security and core national interests.

After Ukraine, the US’s ongoing efforts to bring the Gulf Arab states into the fold over its heightened competition with China won’t be a stroll in the park and will likely come against enormous challenges constraining the bilateral relations with many regional powers.

Where ties go from here

The GCC’s strategic neutrality over Ukraine has buttressed the downward trends in US-GCC relations. Although strains aren’t equally shared across all Gulf countries, relations with the US are most represented by the worsening and chronic lack of depth in their ties with Washington, coupled with the Middle East’s rising multipolar order as a result of China and Russia actively increasing their influence in the region.

Notably, Saudi Arabia and the UAE are frustrated with the perceived decline in the United States’ commitment to the region’s security and its renewed focus on confronting China in the Indo-Pacific. They share the view that the Barack Obama administration overlooked their security concerns and interests by seeking to wrap up the Iran nuclear deal to integrate Tehran into the regional order while ignoring its destabilizing actions. They demand consultation on any new agreement but feel that President Biden might be determined to chart the same course and expect the GCC states to toe the line.

The two countries prefer to avoid taking sides so as not to jeopardize their partnership with Russia on conflicts unrelated to their security or territorial integrity or the security of the US.

Moreover, Riyadh and Abu Dhabi are bewildered by what they see as double standards in the US’s swift and robust response to the invasion of Ukraine compared to what they view as a feeble, indecisive, and half-baked effort to defend them against Houthi (and Iranian) aggression.

President Biden renewed the US commitment to Saudi Arabia’s security on February 9 and deployed a squadron of F-22 fighter jets and the USS Cole to the UAE after January’s unprecedented Houthi missile and drone attack on Abu Dhabi. However, the two influential US allies think this doesn’t even come close to the level of support that Ukraine has received from the West since the invasion.

The difficulties in the relationship don’t represent temporary tendencies directly related to the Ukraine war. They predate the crisis and run deeper into the fundamental pillars of the partnership, which was built primarily on mutual trust in addition to alignment on security interests and preserving global energy market stability.

The Gulf Arabs’ hedging towards US policy preferences has precedent in Syria, Yemen, Libya, and the Iran Deal. But never before have they demonstrated this level of publicized discontent and mistrust of US commitment to their regional visions and interests. The frustrations on both sides are long term and are expected to outstrip Ukraine and perhaps remain as hindering factors in any future attempt by China to invade Taiwan.

Moreover, despite its destabilizing effect on the energy market, the Ukraine war has seen the Gulf coffers receive billions due to the price hikes. However, a conflict between China and the West would have devastating effects, with the potential closure of strategic maritime chokepoints, such as the Malacca Strait, severing a significant chunk of energy exports to the South China Sea and East Asia at large.

The Gulf Arab states’ strategic balancing would emanate from a desire to avoid the spillovers of any such direct confrontation, which would potentially destabilize their region.

Ukraine has plenty of lessons about the GCC and China’s growing strategic alignment with the US. Unless the Biden administration recalibrates the trajectory of its commitment to the Middle East’s security and takes GCC states’ concerns about the future nuclear agreement with Iran seriously, the Gulf countries’ resistance to US pressure to “politicize” their economic interests with China will soon reach unprecedented levels.

Ahmed Aboudouh is a nonresident fellow with the Atlantic Council. He is also a journalist with The Independent in London. Follow him on Twitter: @AAboudouh.

Further reading

Wed, Feb 23, 2022

China and Russia are proposing a new authoritarian playbook. MENA leaders are watching closely.

MENASource By Ahmed Aboudouh

It’s on major Western democracies to make democracy appealing again by aggressively filling the gaps China and Russia exploit to make the world more accommodating to their political models and the new trend of rising authoritarianism.

Thu, Jan 27, 2022

China is trying to create a wedge between the US and Gulf allies. Washington should take note.

MENASource By Jonathan Fulton

Recent events indicate that leaders in Beijing are no longer satisfied with the logic of strategic hedging and are pursuing a more muscular approach to the Gulf.

Thu, Feb 3, 2022

China may now feel confident to challenge the US in the Gulf. Here’s why it won’t succeed.

MENASource By Ahmed Aboudouh

Despite China’s growing aggressive approach towards the United States in the region, it has no detailed plan to execute it successfully.

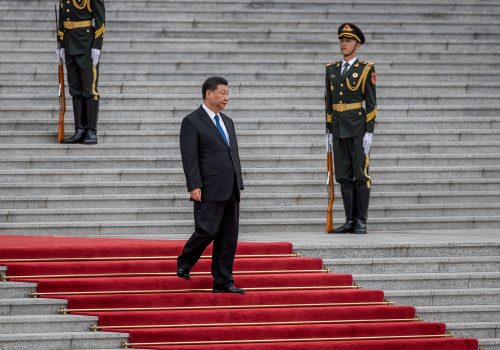

Image: China's President Xi Jinping and Saudi King Salman bin Abdulaziz Al-Saud attend a welcoming ceremony at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, China, March 16, 2017. REUTERS/Thomas Peter