China is trying to create a wedge between the US and Gulf allies. Washington should take note.

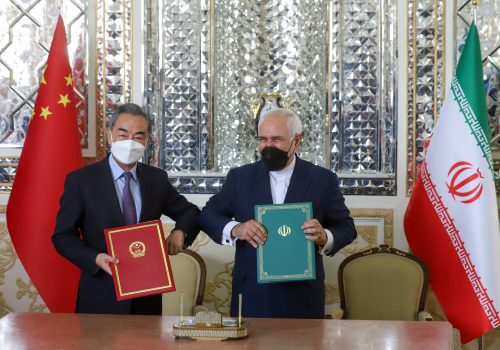

In mid-January, China-Middle East relations made headlines when the foreign ministers of six regional countries—Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Oman, Bahrain, Turkey, and Iran—as well as the secretary general of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) traveled to China’s Wuxi province on official visits. While the meetings didn’t result in the announcement of any new initiatives, they reinforced that Beijing is increasingly perceived as an important political and diplomatic actor in the region.

After the meetings, however, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi issued a statement designed for leaders and publics in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), promoting China as a great power with an approach to the region dramatically different from that of the US. The Middle East, according to Wang, “is suffering from long-existing unrest and conflicts due to foreign interventions…We believe the people of the Middle East are the masters of the Middle East. There is no ‘power vacuum,’ and there is no need of ‘patriarchy from outside.’”

Chinese leaders have long been critical of the United States’ approach to MENA but were reluctant to challenge US dominance openly; their regional interests were largely satisfied under the US-led status quo. They didn’t bandwagon or actively participate with the US in support of American policy objectives, such as the 2003 war in Iraq, but neither did they push against it.

Instead, Beijing adopted a strategic hedging approach, which international relations theory tells us is an option for second-tier powers who want to continue deriving benefits from a regional order that suits their ambitions. A successful hedging strategy focuses on deepening engagement with different countries in the region, alienating no one, and not antagonizing the strongest country. It usually starts with stronger economic ties and builds towards deeper political relations, slowly strengthening influence and power in the region. This is an apt description of China in the Gulf over the past twenty years.

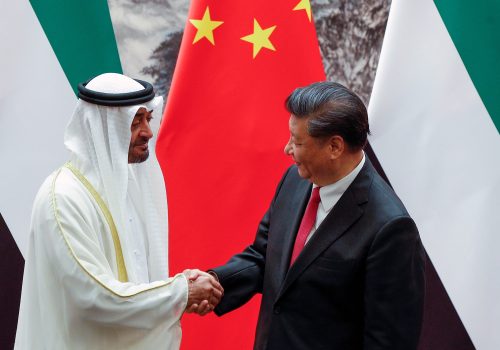

Recent events indicate that leaders in Beijing are no longer satisfied with the logic of strategic hedging and are pursuing a more muscular approach to the Gulf. In November 2021, The Wall Street Journal reported that China was building a military facility in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), although the Emirati government stated that this was a mischaracterization of the project. Presidential Advisor Anwar Gargash said, “The UAE’s view was that these certain facilities in no way could be construed as military facilities.”

Whatever the nature of the project, it clearly set off warning alarms in Washington and came at a time when the US and UAE were navigating an already complex F-35 sale—since canceled in December 2021 by the Emiratis—demonstrating how Sino-Emirati relations were a growing source of friction between Washington and Abu Dhabi. In the past, Beijing would have avoided this as stable US-GCC relations were good for business. Now, however, China seems willing to exploit those pressure points in order to both differentiate itself from the US and to create friction between Washington and its regional partners.

Podcast series

Listen to the latest episode of the China-MENA podcast, featuring conversations with academics, government leaders, and the policy community on China’s role in the Middle East.

Another example came from a December 2021 CNN report that revealed that Beijing is helping the Saudis develop a domestic ballistic missile system. Both Saudi Arabia and the UAE are looking to build their capacity in this multi-billion dollar sector to create jobs and lessen their reliance on foreign arms imports as key parts of their Vision 2030 economic diversification programs.

It’s not the first time China has cooperated with the Kingdom on ballistic missiles; the Dong-Feng sale in the 1980s was instrumental in the two establishing diplomatic relations. It’s also not the first instance of the two working together on the domestic production of weapons. In 2017, there was a joint venture between China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation and the King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology to build a factory in the Kingdom to assemble and service Chinese Ch-4 drones. At the same time, Chinese support for Saudi Arabia’s domestic ballistic missile program—while the US is focused on nuclear negotiations in Vienna to revive the 2015 Iran nuclear accord—is likely not welcome in Washington.

It’s safe to say that China is no longer hedging. Instead, it seems to be wedging: trying to create and take advantage of space between the US and its allies and partners in MENA. This is consistent with Chinese behavior in other regions, such as Asia and Europe. Beijing sees Washington’s global alliance network as a threat, so it would make sense for China to try to disrupt these wherever possible.

In the Gulf, however, it’s an alarming indication of how badly the US-China relationship has deteriorated. Both powers’ core regional interests are highly compatible: they want continued freedom of navigation, a stable regional status quo, and for Gulf energy to continue to flow to global markets. If Washington and Beijing could get their bilateral relationship back on track—a big ask given the political climates in both countries—the Gulf could be a region where this convergence of interests results in policy coordination to solve the many pressing issues that influence events far beyond its shores. If not, the risk of great power competition could further destabilize a shaky regional order.

The Chinese foreign minister’s message of a Middle East that doesn’t need a “foreign patriarch” may ring hollow given the role of the US Patriot interceptors in defending the UAE from Houthi missiles this month. But in a region with complicated feelings about the US—alternating between concerns of retrenchment and hopes for a robust but less militarized role—Wang’s articulation of an alternative great power approach to MENA is one that resonates. Don’t expect to see China replacing the US role—there is no interest or capacity for that—but do expect more messaging and actions that create friction between Washington and its regional allies and partners.

Jonathan Fulton is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council and host of the China-MENA Podcast. He is also an assistant professor of political science at Zayed University in Abu Dhabi. Follow him on Twitter: @jonathandfulton.

Further reading

Mon, Feb 22, 2021

China is happy about the Abraham Accords and the GCC crisis coming to an end

MENASource By Jonathan Fulton

Middle Eastern dispute resolution benefits lots of countries with interests in the region and several can be expected to capitalize. However, given China’s increasingly deep MENA footprint, it will capitalize more.

Thu, Apr 1, 2021

Mr. Wang goes to the Middle East

MENASource By Jonathan Fulton

This marks the first time that every GCC country has received a senior Chinese official in the same calendar year. China’s MENA footprint is only getting deeper.

Fri, Jan 24, 2020

China’s Persian Gulf strategy: Keep Tehran and Riyadh content

MENASource By

The current tensions between Washington and Tehran have been a major stress test for China’s Persian Gulf strategy.

Image: Abu Dhabi's Crown Prince Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed al-Nahyan walks with Chinese President Xi Jinping at the Presidential Palace in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates July 20, 2018. WAM/Handout via REUTERS.