China may now feel confident to challenge the US in the Gulf. Here’s why it won’t succeed.

A string of missile strikes by the Iran-backed Houthis on the United Arab Emirates’ (UAE) capital Abu Dhabi on January 17, 24, and 31 and February 2 has put China in a difficult position. It revealed that, despite China’s growing aggressive approach towards the United States in the region, it has no detailed plan to execute it successfully.

The attacks comprised four waves—the January 31 strike happened during the Israeli president’s remarkable visit to the UAE—of drone, cruise, and ballistic missiles, targeting Abu Dhabi airport, an oil storage, and the al-Dhafra Airbase—hosting US troops—and resulting in three civilian casualties.

The Houthis’ strikes targeted a country where many Chinese citizens live and a significant number of their companies operate; the UAE hosts more than two hundred thousand Chinese citizens running a vast pool of more than six thousand companies. It’s also the largest logistical hub for Chinese trade and more than 60 percent of Chinese goods in the region transit through it.

The Houthis’ ultimate goal behind the recent and continued escalation is to threaten the UAE’s longstanding global brand as the safest and most secure environment for business in a volatile region.

But instability and its impact on China’s citizens and economic interests in the UAE weren’t the only threat the Houthi attacks brought in regard to China’s position and strategic outlook in the region. Conflicting implications have emerged during and after the Houthi strikes that positioned Beijing in the crosshairs of a number of strategically-negative factors.

First, the flurry of drone and missile attacks and the US’s help—directly by intervening to defend the UAE or indirectly by providing them with missile defense systems—bolstered the US position as the interlocutor of regional stability. On the other hand, China largely maintained its silence, which should raise some questions in the Gulf about China’s true objectives in the region.

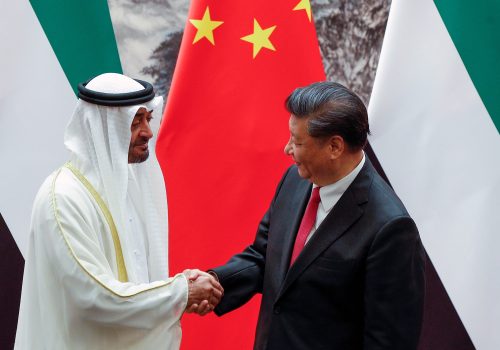

Beijing’s growing sensitivity towards US hegemony reached unprecedented levels in 2021 and is expected to further grow this year. China has shown that it has become more confident to proactively challenge US regional dominance in previously untapped sensitive spheres, such as security, technological innovation, and data security.

In November 2021, The Wall Street Journal reported that the UAE government had stopped work on a Chinese military facility in Khalifa Port in Abu Dhabi. UAE officials insist that it had no military purpose. A month later, CNN published satellite images showing ongoing work on Saudi Arabia’s missile program in a site built with China’s help.

On January 26, Chinese Defense Minister General Wei Fenghe’s video meeting with Saudi Deputy Defense Minister Prince Khalid bin Salman received significant publicity in Chinese media, implying the two countries are ready to have closer military ties as the US retrenches from the region. General Wei suggested that the two sides should “strengthen coordination and jointly oppose hegemonic and bullying practices, to safeguard…the interests of developing countries together.”

China is showing greater confidence to make its aggressive approach known in an apparent bid to create an alternative narrative on the Middle East and North Africa’s (MENA) regional order. After the group visit of six MENA foreign ministers—from Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Oman, Bahrain, Turkey, and Iran—in January, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi tried to formulate China’s new assertiveness, a message Beijing was previously always careful to avoid. He said: “We believe the people of the Middle East are the masters of the Middle East. There is no ‘power vacuum’ and there is no need of ‘patriarchy from outside.’”

China played a front role in condemning the first wave of Houthi strikes on Abu Dhabi in the United Nations Security Council. In a statement on January 21, China described it as “heinous terrorist attacks.” But its silence on the second wave, on January 24—which targeted a military facility used by the US army—is noteworthy.

China can sometimes be proactive in backing Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states against Houthi attacks. In November 2020, Beijing condemned a missile attack on an oil facility in the Saudi city of Jeddah. On March 9, China joined ranks with the US to decry another Houthi attack on Saudi oil and military facilities, saying, “We support Saudi Arabia’s efforts to safeguard security and stability.”

China’s silence on recent strikes on the UAE suggests that it has grown more eclectic in its reaction—or non-reaction—towards serious developments in the Gulf according to its perception of their impact on US interests. Moreover, it indicates that the Chinese Communist Party may have an overall vision to be more pugnacious towards the US hegemonic position in the Gulf, although it lacks day-to-day plans on achieving its objectives at the policy level.

The US and China’s different reactions are an apt epitome of the new dynamics in China-US competition in the MENA region and perhaps an indication of China’s lack of a playbook regarding Gulf security.

Podcast series

Listen to the latest episode of the China-MENA podcast, featuring conversations with academics, government leaders, and the policy community on China’s role in the Middle East.

However, the new approach shouldn’t be taken as a Chinese bid to fill the vacuum as a regional security patron, even as the People’s Liberation Army’s doctrine concentrates troops in the East Asian theater. Any large-scale deployments in the Gulf would first require significant changes in China’s strategy, which emphasizes economic cooperation as its primary vehicle through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

It also shouldn’t be interpreted as a shift away from China’s longstanding interest in maintaining the region’s overall stability, even when military escalations are possibly seen as favorable to China in its simmering rivalry with the US.

The natural takeaway from the above view is to consider China’s new behavior detrimental to the GCC states’ interests, namely the US protection umbrella enjoyed for decades.

But, in reality, China’s aggressive approach provides US regional allies with a strategic opportunity, as it creates a bigger space for the Arab Gulf countries to hedge their bets between two superpowers. It also places greater pressure on the US to align its strategic agenda with the GCC states and, subsequently, reassure them about Washington’s commitments to their security. Moreover, China’s growing influence in the Gulf complicates the US’s plans to pivot to the Indo-Pacific—an objective the GCC states and China share.

Additionally, the Houthis’ missile strikes seem to have caught China off guard. China doesn’t like to see this kind of escalation between two of its partners—in this case, the UAE and Iran (the Houthis’ principal backer). The attacks on Abu Dhabi and China’s largely muted reaction reinforce its “non-alliance” principle—an insurance policy against being dragged into regional conflicts or having to pick sides and reveal an unready China.

Finally, the raids also confronted Chinese policymakers with a difficult question: Will China start to develop a more sophisticated security-focused approach rather than adhering to the economic-heavy policy it currently adopts?

If it wants to challenge the US role in MENA effectively, China will have, in the future, to find the answer to this question and solve its “free-riding” problem—that is, rethink its constant pursuit of more influence in the region without entanglement in its Beijing’s rivalry.

Wang’s call for a new regional mechanism that excludes the US’s dominant influence reveals a desire to decentralize the debate on the future of the regional order away from the US centrality. However, events like the Houthis’ strikes on the UAE indicate that, when it gets down to the nitty-gritty of challenging the US posture in the Gulf, China doesn’t seem to have a clear plan of action yet.

Ahmed Aboudouh is a nonresident fellow with the Atlantic Council. He is also a journalist with The Independent in London. Follow him on Twitter: @AAboudouh.

Further reading

Thu, Jan 27, 2022

China is trying to create a wedge between the US and Gulf allies. Washington should take note.

MENASource By Jonathan Fulton

Recent events indicate that leaders in Beijing are no longer satisfied with the logic of strategic hedging and are pursuing a more muscular approach to the Gulf.

Wed, May 26, 2021

Do China and Russia want to replace the US as mediators in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict?

MENASource By

In this brief reaction piece, three experts from our working group on Chinese and Russian power projection in the Middle East offer their views on the viability of Russia or China bringing the parties closer to the negotiating table.

Mon, Feb 22, 2021

China is happy about the Abraham Accords and the GCC crisis coming to an end

MENASource By Jonathan Fulton

Middle Eastern dispute resolution benefits lots of countries with interests in the region and several can be expected to capitalize. However, given China’s increasingly deep MENA footprint, it will capitalize more.

Image: China's State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi and UAE's Foreign Minister Abdullah Bin Zayed Al Nahyan during their meeting in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, March 28, 2021. WAM/Handout via REUTERS