Under Macron’s leadership, France is leading a middle power strategy in the Gulf. Here’s how.

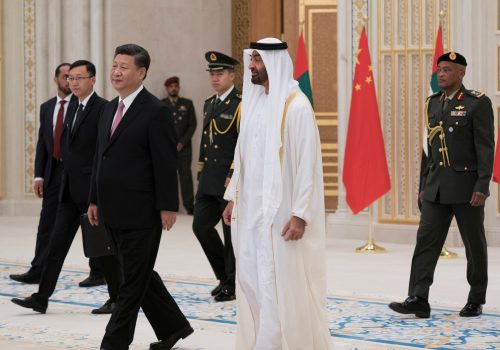

In the second half of July and just days after US President Joe Biden’s visit to the Middle East, Emirati President Mohammed bin Zayed (MBZ) and Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MBS) consecutively traveled to Paris and met with French President Emmanuel Macron. The meetings are the latest of a long series of high-level talks between France and both Gulf partners. Prior to his visit last July, MBZ had met Macron three times—in September 2021, December 2021, and May—in the past twelve months, while the French president already met MBS during a trip to Saudi Arabia in December 2021.

These consultations underline the revived ambitions of France in the Arabian Peninsula under the Macron presidency. France is positioning itself as a Western partner that, although may not be a substitute to Washington, is one that provides, as one former French ambassador explained to me, a “convenient and credible” option to those Gulf leaders eager to diversify their partnerships. France under Macron presents itself as a Western middle power promoting a multilateral environment and, therefore, unlikely to get local partners trapped in the US-China competition. In essence, this is an old French trope dating back to Charles de Gaulle’s posture during the Cold War, but it has now been revived in light of the tense relations between Riyadh, Abu Dhabi, and Washington.

So far, this French policy has been more successful in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) than in Saudi Arabia. Since opening a French naval base in Abu Dhabi in 2009, Paris deploys about 650 French soldiers inside the country. While it’s true that these numbers pale in comparison to the 3,500 US military personnel in the UAE, the strategic rapprochement between Paris and Abu Dhabi is also palpable through their shared views on regional issues. French and Emirati officials share similar concerns on the spread of political Islam and, in particular, groups affiliated with the Muslim Brotherhood. Paris is not as maximalist as Abu Dhabi in its condemnation of the Brotherhood but, just like the UAE, France supported regional strongmen like Egypt’s President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi or Libya’s Marshall Khalifa Haftar.

The French-Emirati strategic dialogue goes beyond the Middle East. In recent years, the UAE played a significant role in consolidating French ambitions in the Indo-Pacific. The French naval command for the Indian Ocean, nicknamed “Alindien,” operates from Abu Dhabi. In late 2020, the UAE, while chairing the presidency of the Indian Ocean Rim Association, supported French membership in the regional body (France is the only member without mainland presence in the Indian Ocean). Finally, Paris is keen on developing trilateral exchanges with Abu Dhabi and New Delhi as a way to foster its minilateral initiatives in the Indo-Pacific. This includes a military leg, with the first French-Indian-Emirati naval exercises held in 2021.

France’s relations with Saudi Arabia have been more complicated. Initially, Macron’s personal relationship with MBS was reportedly much colder than the one he built with MBZ in Abu Dhabi.

Prior to Macron’s election in 2017, Paris’ ties to the Al Saud family had steadily declined. In fact, Macron’s first visit to Saudi Arabia in the fall of 2017 seemed to replicate the misfortunes of his predecessors, Nicolas Sarkozy and François Hollande. The fragile regional context of the trip did not help. A few months earlier, MBS launched a blockade of Qatar and, by then, he was holding Lebanese Prime Minister Saad Hariri captive in Riyadh. According to French diplomats, Macron’s first exchange with bin Salman was tense. The French leader was reportedly puzzled by the Saudi prince’s demand that France suspend its ties with Qatar—a request he quickly dismissed. Instead, Macron insisted on convincing the Saudi prince to let Hariri leave and come to Paris.

Despite that troubling first encounter, Macron refused, a year later, to take drastic measures against Saudi Arabia after the assassination of journalist Jamal Khashoggi. Contrary to European allies like Germany or the Netherlands, France refrained from suspending its arms transfers to the Kingdom. However, Macron did give a hard talk to MBS on the sidelines of the G20 summit, a month after Khashoggi’s death, that was caught on camera—but that was all.

Afterward, French-Saudi relations improved. Macron’s visit to Jeddah in December 2021 was seen as the first major meeting of MBS with a Western leader since the Khashoggi murder. During that visit, Macron turned the Lebanese file into the main area of cooperation with Riyadh by announcing a joint humanitarian initiative to bring Saudi Arabia back to Lebanon after years of disengagement. It remains to be seen if this humanitarian program involving a $30 million aid package can deliver on its promises. Still, Lebanon was again at the top of the agenda for the Saudi crown prince’s visit to France in late July.

The French rapprochement with the UAE and Saudi Arabia has raised important issues in Paris and in the region. Domestically, it led some observers to express concerns regarding French endorsement of Emirati and Saudi foreign policies, be it on Libya—where the military support to Haftar ended in his failed offensive on the capital Tripoli in 2020—or on the Yemen war—where the Macron government rejected media claims that French military equipment had been used by the Saudi coalition against civilians.

At the regional level, this French policy also put Paris at odds with another traditional Gulf partner: Qatar. According to French diplomatic sources, Qatari officials expressed deep unease with the France-UAE rapprochement occurring in the middle of the blockade imposed by Riyadh and Abu Dhabi on Doha. The French government may have insisted on its official neutrality vis-a-vis the Gulf dispute, but its economic and security interests de facto tilted towards the UAE. There is reportedly a desire among staff at the French Foreign Ministry to rebalance this Gulf policy, but the July reception at Elysée Palace for MBZ manifested a different view from Macron’s presidential palace.

Finally, France will inevitably face a conundrum regarding its stance or lack thereof on China’s growing influence in the Gulf. Thus far, France remained skeptical about US concerns, even after the revelations of a Chinese port project in the UAE in 2021. In fact, viewed from Paris, the American-Emirati tensions of the past year, leading to the suspension of the F-35 deal, had a positive consequence, with the major sale of eighty French Rafale fighter jets to Abu Dhabi in December 2021.

The more the US pressures Gulf states to take a stand on China, the more France can promote a non-aligned rhetoric that pleases Emirati and Saudi leaders. But it works as long as France, like its Gulf partners, can afford to escape the logic of great power competition. On the ground, this is already proving to be a delicate gamble. Like their American colleagues, French officers at the Abu Dhabi naval base expressed to me their suspicions over Chinese activities in the area. Eventually, as China—as well as Russia—keep deepening their involvement in the Middle East, France may find it impossible to promote its non-aligned alternative.

Jean-Loup Samaan is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council. He is also a senior fellow at the Middle East Institute of the National University of Singapore. Follow him on Twitter: @JeanLoupSamaan.

Further reading

Thu, Jan 27, 2022

China is trying to create a wedge between the US and Gulf allies. Washington should take note.

MENASource By Jonathan Fulton

Recent events indicate that leaders in Beijing are no longer satisfied with the logic of strategic hedging and are pursuing a more muscular approach to the Gulf.

Wed, Feb 23, 2022

China and Russia are proposing a new authoritarian playbook. MENA leaders are watching closely.

MENASource By Ahmed Aboudouh

It’s on major Western democracies to make democracy appealing again by aggressively filling the gaps China and Russia exploit to make the world more accommodating to their political models and the new trend of rising authoritarianism.

Thu, Feb 3, 2022

China may now feel confident to challenge the US in the Gulf. Here’s why it won’t succeed.

MENASource By Ahmed Aboudouh

Despite China’s growing aggressive approach towards the United States in the region, it has no detailed plan to execute it successfully.

Image: French president Emmanuel Macron receives Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman Al Saud (known as MBS) for a dinner at the Elysee Palace in Paris, France on July 28, 2022. Photo by Balkis Press/ABACAPRESS.COM