What does the Arab Street think of China and Russia? The answers may surprise you.

This article is part of a strategic collaboration launched by the Atlantic Council (Washington, DC), the Emirates Policy Center (Abu Dhabi), and the Institute for National Security Studies (Tel Aviv). The authors are associated with the initiative’s Working Group on Chinese and Russian Power Projection in the Middle East. The views expressed by the authors are theirs and not their institutions’.

Sino-Russian relations today are enjoying their “best period in history” across multiple dimensions, according to Russian and Chinese officials. China’s President Xi Jinping has called Russian counterpart Vladimir Putin his “best friend,” while Putin recently noted that a military alliance with China is not needed but cannot be ruled out. On the diplomatic front, all of China’s vetoes at the United Nations Security Council between 2007-2017 have been joint Russia-Chinese vetoes. Prior to 2007, none were. The apparent “dangerous convergence” in Sino-Russian relations is largely perceived as an entente or an axis of authoritarians that threatens the West and the current global order.

This tendency to lump China and Russia together in the Arab world raises two questions that are addressed in this analysis. First, is this practice replicated in the Arab countries of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA)? Second, are perceptions about China and Russia shared by MENA elites and the public? Building on previous posts that analyzed MENA’s interests in engaging these states, we answer these questions by examining polling data across MENA and within particular states.

Are China and Russia perceived as a tandem in the Middle East?

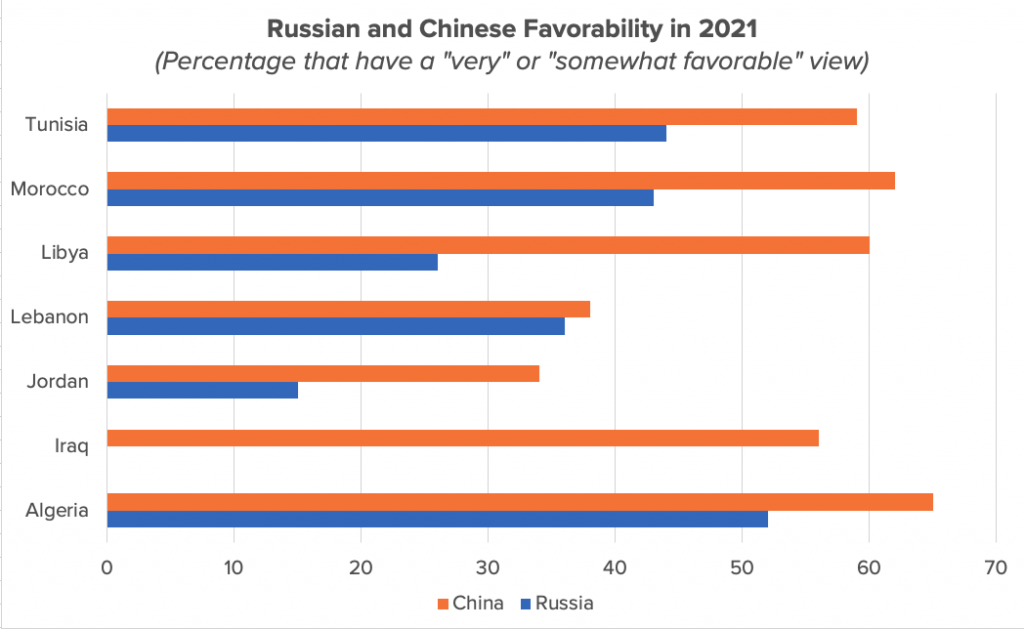

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) is experiencing rising favorability across the Middle East, which aligns with its strategic aims in a region where it casts itself as an alternative partner compared to other great powers. While usually styled in analysis as an alternative to the United States, this attitude might also extend to Russia. In the Arab Barometer’s latest data from the current Wave VI of polling—which is ongoing amidst COVID-19—China’s favorability ranged as high as 65 percent in Algeria to 34 percent in Jordan (Chart 1). While there is a spectrum of responses to China, the People’s Republic still ranks higher than Russia by an average of 17 points. This gap is widest in countries most proximate to Russian involvement in the crises in Syria and Libya (Jordan by 19 points and Libya by 34 points). China has practiced a much more restrained policy in these arenas, possibly sustaining less damage to its favorability.

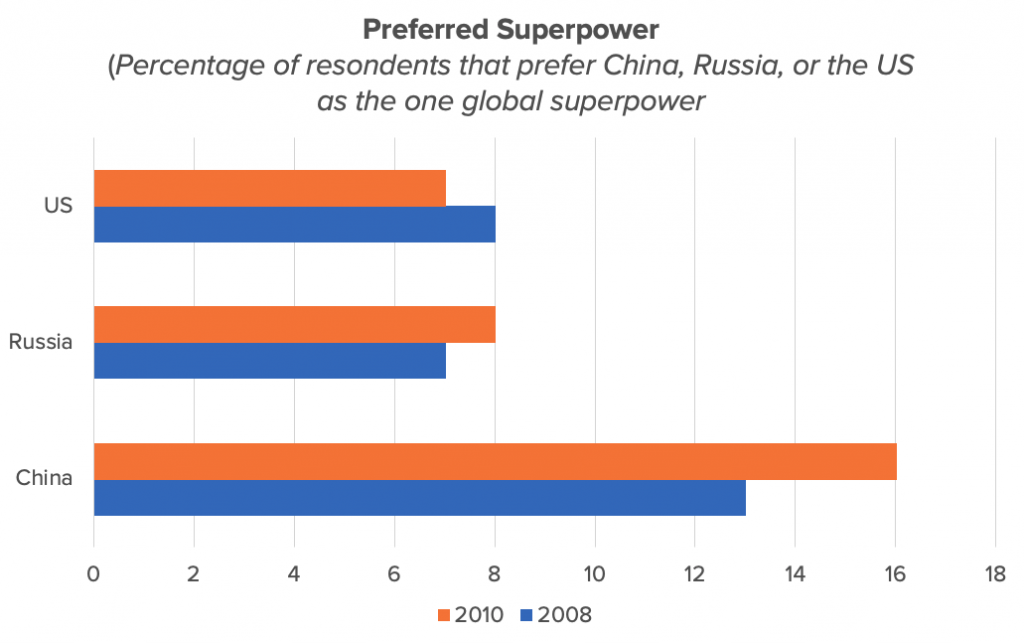

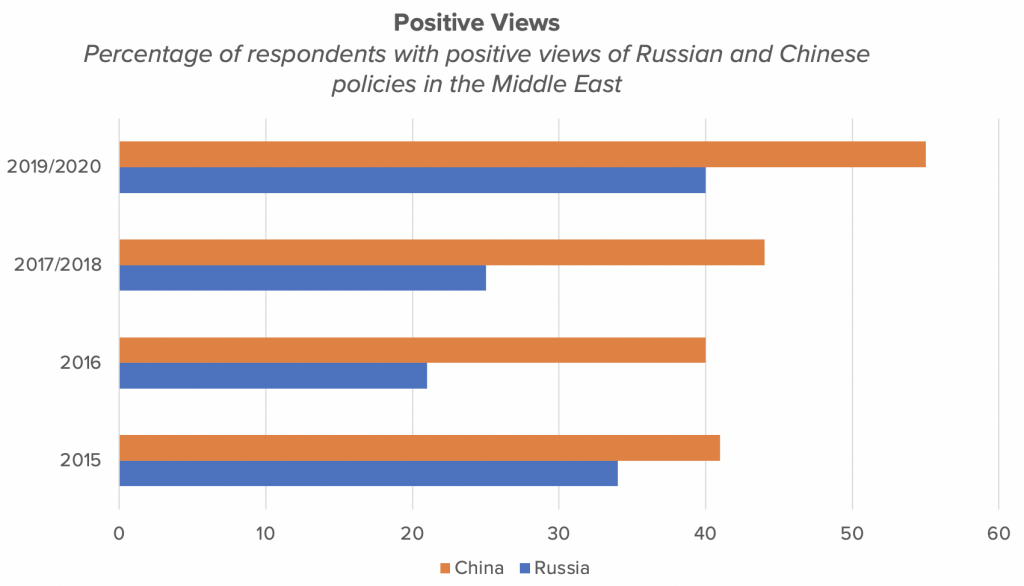

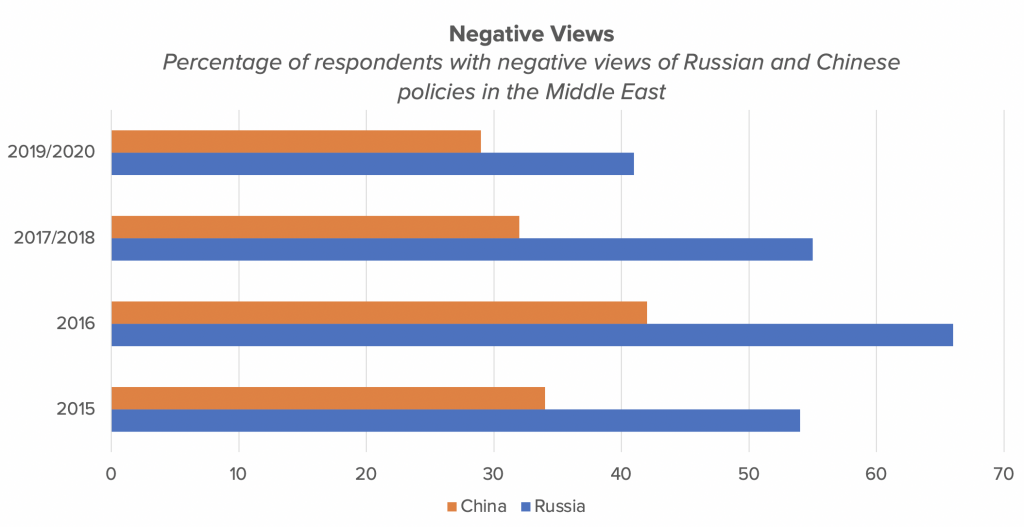

The distinction between MENA views of Russia and China highlighted in the Arab Barometer is also corroborated by other polls. Even before Russia’s military intervention in Syria, which has divided opinion in the Middle East, the Zogby International/University of Maryland surveys from 2008 and 2010 indicate that twice as many respondents prefer China to Russia in a hypothetical world with one superpower (see Chart 2). The Arab Opinion Index (see Charts 3 and 4) conducted from 2015 to 2020 suggests an upswing among those who are positively disposed towards Russia’s and China’s policies in MENA since 2016. Between 2015 and 2018, however, a majority of respondents viewed Russia’s policies negatively. By comparison, Arabs have been consistently more receptive towards China in the Middle East by a wide margin. With Zogby/Maryland and Arab Opinion Index polls covering some countries—notably Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Iran, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE)—outside the scope of the Arab Barometer, the fact that their results are largely aligned means that we can say with a high level of confidence that the MENA public does distinguish between engagement with Russia and China.

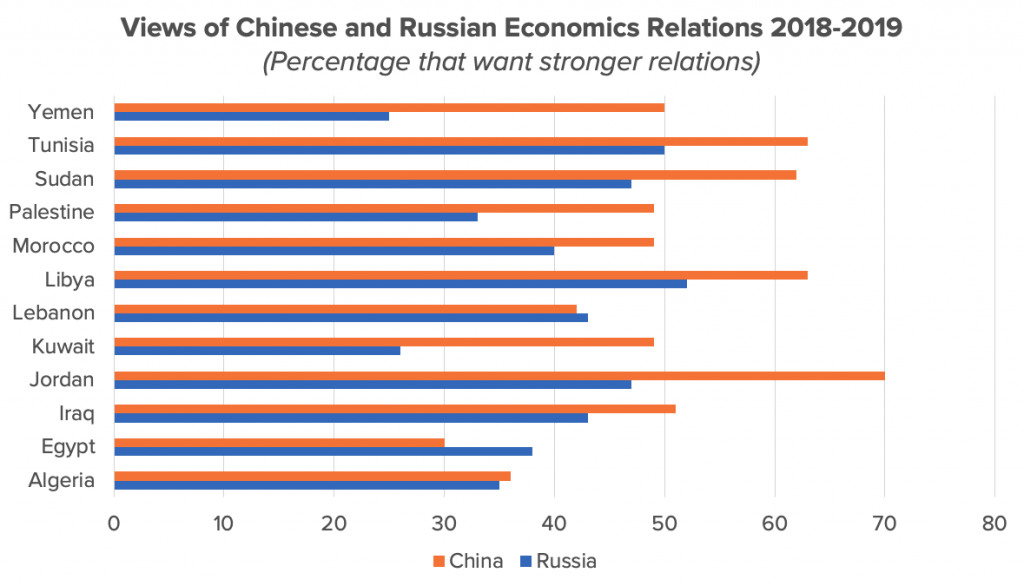

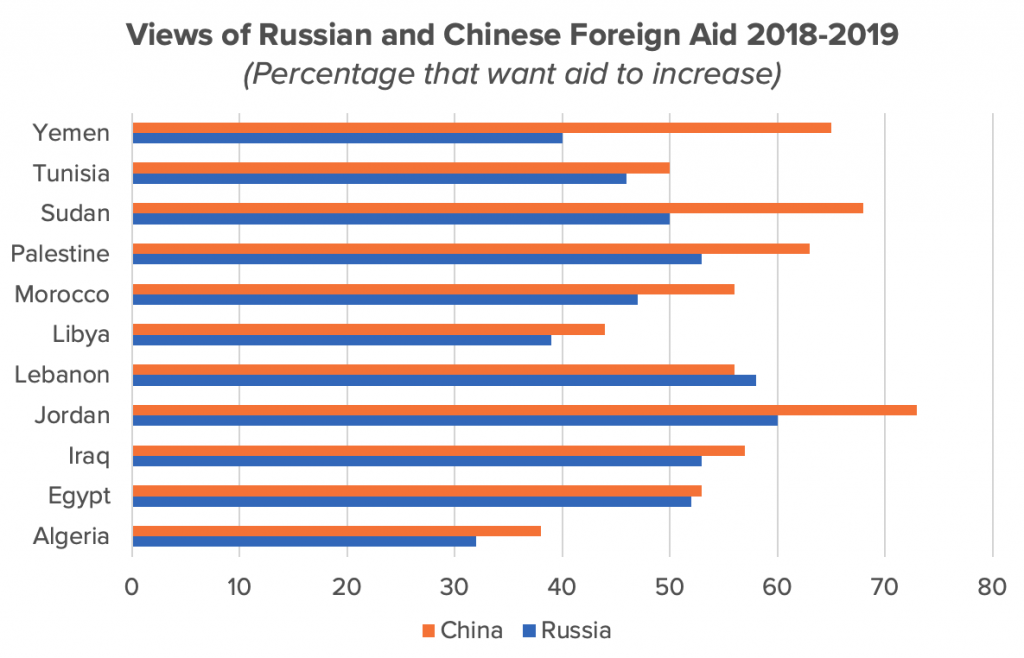

On average, this preference for China carries over to views about economic relations. In Wave V of the Arab Barometer across the Arab world, China averaged 11 points higher than Russia (Chart 5). China also averages 11 points higher than Russia in respondents who want foreign aid to increase (Chart 6).

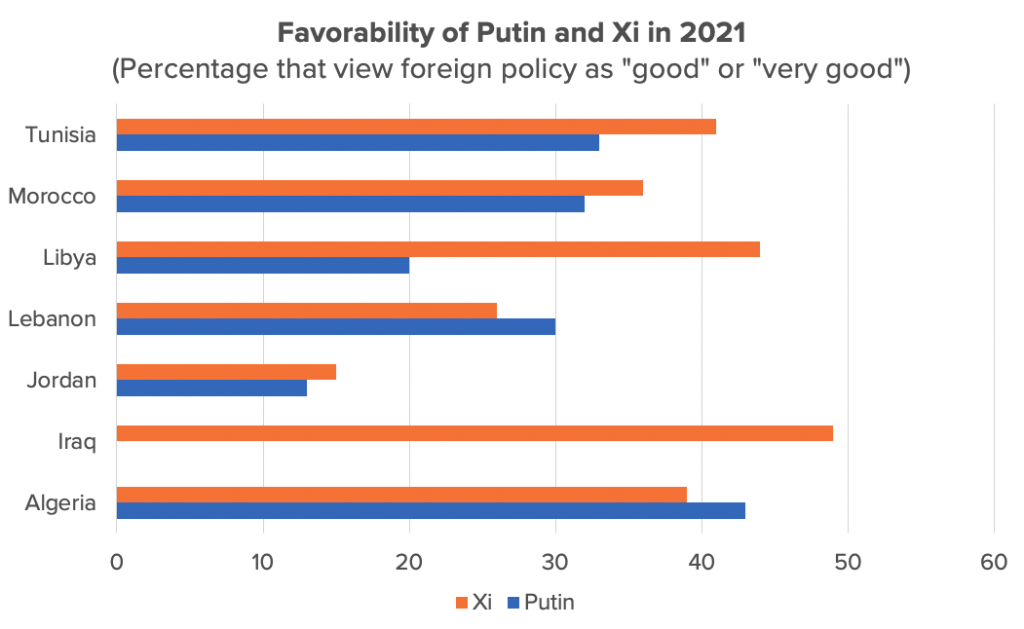

This extends to attitudes about leadership. Prior to 2018, the public in MENA had a lower level of confidence in President Putin’s leadership in world affairs than the global median, according to Pew Research surveys. However, in 2018 and 2019—the most recent years for which polling data is available—they expressed significantly greater confidence in Putin compared to previous years and the global median. With 38 percent of MENA respondents expressing confidence in Putin in 2019, this put the Russian president on par with China’s President Xi at 37 percent. At the same time, a much higher share (47 percent) of the MENA public admits to little confidence in Putin compared to Xi (34.5 percent). Wave VI of the Arab Barometer has likewise displayed more confidence in President Xi than President Putin by an average of 8 points (Chart 7).

The different perceptions of China and Russia in MENA are partly rooted in history. Whereas opinion about the Soviet Union (USSR) was divided during the Cold War—the Gulf states viewed the USSR as an adversary, whereas the secular and revolutionary states saw it as an ally against the US—China’s lower international profile elicited little negative reaction.

China and Russia’s current policies in MENA also explain local perceptions. For instance, Russia has involved itself in local conflicts in part to underline its reach and relevance as a global power. By contrast, China has exercised strategic restraint to avoid entanglement in the region’s politics and has, consequently, minimized the number of detractors. Additionally, China’s focus on economic exchanges facilitates its so-called approach of “win-win cooperation,” especially with the roll-out of the Belt and Road Initiative, a cooperative infrastructure financing mechanism wholeheartedly supported by the Chinese Communist Party. On the other hand, Russia’s relative financial constraints render it a less attractive partner than the PRC.

Are MENA elites and public in sync on China and Russia?

The relative paucity of public opinion survey data in the Middle East compared to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development countries makes it challenging to disaggregate the views of elites and the Arab street. Nevertheless, we offer a few tentative, data-driven insights.

A 2018 survey conducted by the well-regarded Amman-based NAMA polling organization found that Jordanian elites were much more likely than the mass public to prefer that their country engages with non-Arab/Muslim states. Even so, elites ranked Russia as only the fifth most preferred ally; neither China nor Russia were included in the top eight preferred allies among the mass public. Russia’s generally poor image in Jordan is consistently reiterated in Pew Research surveys and is likely a consequence of its policies in Syria. The huge influx of Syrian refugees, numbering between 660,000 to 1.5 million, has raised fears of competition for resources and opportunities among already vulnerable Jordanians. Nevertheless, Jordan’s relations with Russia continue to improve, buoyed by King Abdullah’s 2019 endorsement of a strong Russian presence in the Middle East and the recent approval of the use of the Sputnik vaccine in Jordan.

Likewise, in Wave V of the Arab Barometer, elites were more likely to support Chinese investment. Respondents with a university degree were significantly more supportive of closer economic relations with China than those with a secondary degree or less. This is represented by an average difference of 9 points. Closer economic ties with Russia also polled more highly with those with education beyond a secondary degree, with an average point difference of 8.

Putin enjoys warm relations with leaders in Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Egypt. The high five between Putin and Saudi Crown Prince Mohamed bin Salman in 2018 seemed to epitomize a “bromance.” The Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi Mohamed bin Zayed referred to Putin as “my brother and friend” in 2019 and concluded a Declaration of Strategic Partnership the previous year. As for Egypt’s President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, he sent his eldest son to serve as military attaché in Moscow.

While President Xi’s leadership style relies less on personality than his Russian counterpart, Middle Eastern dignitaries have nothing but warmwords for the composed Chinese head of state. President Sisi has visited China six times since taking office in 2014. By comparison, his predecessor Hosni Mubarak visited China six times over his thirty-year rule.

These elite-level relations, however, do not always appear to be reciprocated by the public. A Zogby poll in 2018 found that 81 percent of Egyptians, 80 percent of Emiratis, and 46 percent of Saudis expressed unfavorable attitudes towards Russia. That at least 85 percent of respondents in these countries object to restoring full relations with the Bashar al-Assad regime in Syria—a policy backed by Russia—may explain the public mood regarding Russia.

Turning to Arab youths, their views on Russia’s rising importance as an ally align with policies pursued by the region’s leaders, as noted by the Arab Youth Survey (see Table 1). What is noteworthy is that Arab youths have not perceived China as one of the top five allies for much of the last decade despite the country’s emergence as a major interlocutor for the region (China only made its inaugural appearance in the 2020 edition of the survey). The Arab Barometer also found that there was no generational preference for Chinese partnership. Tentative evidence that the broader public may share this restrained view of China is suggested by polls in 2020, indicating that 48 percent of Emiratis and 53 percent of Saudis feel that relations with China are not so important/not so important at all—almost the same proportion as those who feel this way about the US.

Top Five Most Important Allies as Seen by Arab Youth

| Rank/Year | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

| 1 | KSA | KSA | KSA | KSA | KSA | UAE | UAE | UAE | UAE |

| 2 | UAE | UAE | UAE | US | UAE | KSA | KSA | Egypt | KSA |

| 3 | Qatar | Qatar | Qatar | UAE | US | Russia | Kuwait | KSA | Egypt |

| 4 | Kuwait | Kuwait | Kuwait | Qatar | Egypt | Qatar | Russia | Turkey | China |

| 5 | US | US | US | France | UK | US | Egypt | Russia | Russia |

The observed divergence between public preferences and a state’s engagements with China and Russia have not seemed to shape or constrain foreign policy thus far. This could be due to authoritarian prerogatives backed up by a repressive state machinery, as seen in Egypt, or to levels of trust in government in the UAE and Saudi Arabia, which are consistently among the highest in the world.

Conclusion: Do public perceptions about Russia and China matter?

Polling is not an exact science, particularly in MENA, where there are deficits in voice and accountability. Reliable public opinion survey research in the region continues to be hobbled by a variety of technical issues, such as the lack of reliable population maps, social taboos that limit household access, and political taboos regarding government surveillance and civil society. These constraints are by no means unique to the region but must be contended within any public opinion analysis.

However, in the last decade, the Arab world has become significantly more amenable to polling, belatedly realizing that good policies require sound data. Although the North African states have been generally more relaxed about polling for some time, promising changes are afoot in the Gulf. Examples include the aforementioned Doha-based Arab Opinion Index that boasts the largest number of Arab respondents, the 2017-2019 Zogby polls commissioned by the UAE government for the Sir Bani Yas Forum, and the National Center for Public Opinion Polls in Riyadh that polled over 77,000 Saudis on public affairs in 2018 alone.

With youths comprising more than 60 percent of MENA’s population and expected long-term declines in hydrocarbon revenues that have facilitated stability through state benefits, some governments in MENA may have to pay occasional heed to public opinion about foreign policy, including engagement with China and Russia, in the future.

With these trends in mind, public opinion can play an increasingly valuable role in understanding policy impacts in MENA. Even with the current limited state of polling tools, it is clear that the Chinese and Russian presence in the Middle East cannot be conflated. Besides having distinctly different approaches to the region, there is evidence that there are widening divergences in public opinion on both powers. This understanding can supplement regional government strategies with China and Russia, as well inform external countries—like the US—more accurately about these dynamics.

Li-Chen Sim is an assistant professor at Khalifa University in the United Arab Emirates.

Lucille Greer is a Schwarzman fellow at the Wilson Center in Washington, DC.

Image: Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed al-Nahyan (R), Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi and UAE's deputy commander-in-chief of the armed forces speaks with Chinese President Xi Jinping during a signing ceremony at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing on December 14, 2015. REUTERS/FRED DUFOUR/Pool