As the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic dominates world

attention, US-Iran tensions are again taking a dangerous turn.

Just two months ago the world was transfixed after lethal attacks against Americans

in Iraq by Iranian-backed forces kicked off a cycle of escalation that resulted

in US President Donald J. Trump’s decision to kill Iranian Major General Qasem

Soleimani. Now, with far less fanfare, that cycle is returning. Americans

have been killed once again during attacks on Iraqi bases, and a series of

strikes have been made by US forces and Iranian proxies within Iraq, with no

immediate sign that the hostilities will abate anytime soon. Iran is

trying to force a US withdrawal, and the United States is trying to protect its

interests and reinforce its red lines. Caught in the middle once again,

Iraq is simultaneously confronting a security crisis, a health emergency, and

an economic free fall—all without the benefit of a functioning government in

Baghdad.

Atlantic Council experts analyze the current situation in Iraq and the growing conflict between the United States and Iran:

Kirsten Fontenrose, director of the Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security’s Middle East Security Initiative:

“Iranian-backed militias killed two Americans on March 14 and the United States is choosing not to strike back? Why not? And for how long? The big picture in play is the fate of the US-Iraq relationship.

“When Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) proxies rocketed the Iraqi base in Taji on March 11,killing two Americans, a Brit, and injuring Iraqi and international troops, the United States responded with strikes on five militia logistics hubs and weapons depots. This response was meant to signal that the United States would retaliate, but with a focus on reducing the militia’s materiel as opposed to personnel.

“Three additional attacks against US forces and trainers followed within a week. Clearly ‘retaliation without escalation’ was not an effective deterrent.

“US Department of Defense (DOD) planners who read intelligence reporting believe that further attacks are on tap. So why hasn’t the United States responded?

“One reason is coronavirus. While Iran continues to enable assaults on the United States and others in Iraq despite the medical crisis at home, the United States does not want to be accused of kicking someone when they’re down. The US cultural brand is strength; Iran’s cultural brand is a half-century of victimhood. This creates a self-imposed double standard that has worked in Iran’s favor during this conflict.

“A second reason was the subject of a debate within the administration about how a continued tit-for-tat would play out. Realists argued that attacks will continue against Americans and Iran will sustain its stranglehold over Iraqi foreign policy, so the United States should respond with action that will diminish Iran’s capability to supply militias in Iraq with support. But this trajectory ends in war. Optimists argued that Iraq is on the verge of political reform driven by protests. But this trajectory ends in zero real change to the system. So the position the US government landed on is somewhere in the middle, and the tagline reads like this, ‘the United States is giving Iraq a chance to exercise its sovereignty.’

“The argument that carries the debate for this position posits that political space must be created for the newly named nominee for Iraqi prime minister to secure the position and attempt to exert state control over armed groups. This is not a favor to Iraq at the expense of the safety of Americans in country. It is a litmus test.

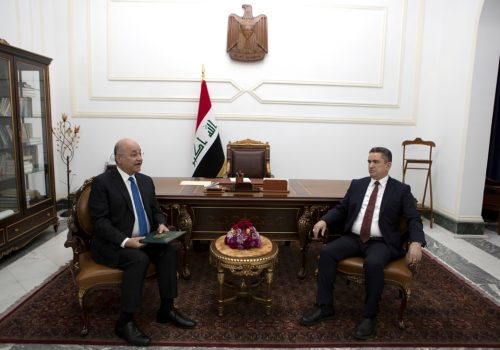

“Iraqis at the public and popular levels decry US air strikes against militia facilities as violations of Iraq’s sovereignty. The United States is listening. But in order to be taken seriously, Iraq must prove it is sovereign. There are two tangible indicators of sovereignty that the United States is watching for: 1) Prime Ministerial Nominee Adnan Al-Zurfi is approved despite Iran’s opposition to him; 2) Unauthorized military activity by Popular Mobilization Front units loyal to Iran is constrained.

“According to the Iraqi Constitution, al-Zurfi has thirty days to form a government. The US Department of Defense is pulling personnel in from far-flung bases around Iraq in a pre-planned drawdown that reflects successes in counter-Islamic State operations. They and UK Ministry of Defense counterparts are pausing training of Iraqi uniformed partners to protect trainers from exposure to the coronavirus. The timing of both decisions is perfect. The lower US profile means less US vulnerability to attack and less Iraqi street discontent with the US presence, which buys Iraqi elites (despite protests, they’re still in charge) a bit more time to try and form a Cabinet. Sectarian and party interests will make this torturous. All the United States can do is leave them alone to do it and make it clear that prioritizing Iraqi interests over those of Iran in the process will be rewarded with partnership and assistance in the areas of economy, governance, and security.

“If there are no indicators of progress in Iraqi Cabinet formation in the coming week (progress will require a lot of pressure by the Iraqi public on their elected officials and a lot of transactional party politics—‘a lot’ being a gross understatement) and attacks on US personnel continue, the United States will need to reassess its posture of patience.

“At that point, US options are limited. Logistics hubs and weapons facilities are finite. Measured strikes to reduce militia capability do not deter them. The risk of escalation is heightened.

“The international community—Europe and parts of the Gulf—should call on Iran to stop directing attacks against US and international troops and trainers while Iraq forms a government. There is no distancing Iran from these groups. Their own leaders openly declare allegiance to the regime.

“Tehran will not want to do this. But if they do not, they acknowledge that their intent to stoke conflict with the United States outweighs their support for stability in Iraq. This puts them in diametric opposition with the rest of the international community and should give Iraqi politicians reason to demand sovereignty.”

Barbara Slavin, director of the Atlantic Council’s Future of Iran Initiative:

“When the United States decided to quit the Iran nuclear deal unilaterally and to try to stop Iran from exporting oil, it put Iraq into an impossible position. Inevitably, Iraq must defer more to its powerful neighbor than to a fickle superpower thousands of miles away. Baghdad’s predicament only worsened with the US assassinations of Soleimani and Popular Mobilization Committee Deputy Chairman Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis on Iraqi soil. The Iraqi parliament gave the United States a peaceful way out in a non-binding vote after the assassinations. But the Trump administration did not take it and even threatened to deprive Iraq of access to its own oil money in the New York Federal Reserve Bank if it ordered US troops to leave.

“A US exit from Iraq is, in my view, now inevitable. How it takes place—with fewer or more US and Iraqi casualties—depends in part on the overall US-Iran relationship and whether the Trump administration can alter its policy of ‘maximum pressure’ to allow for a compassionate response to the coronavirus crisis.

“As the third most affected country after China and Italy, Iran is attracting widespread global support even from its regional rivals. The US position—adding yet more sanctions—is completely out of step with this international consensus. The only recent bright spot in US-Iran relations was the Iranian decision March 19 to release Mike White, a US Navy veteran who had been jailed in Mashhad, as part of a humanitarian furlough of prisoners during the COVID-19 pandemic. White has been handed over to the Swiss, who represent US interests in Iran in the absence of diplomatic ties. Ideally, the Trump administration would now reciprocate in some manner by not adding yet more sanctions on Iran and permitting Tehran to obtain an emergency $5 billion loan it has requested from the International Monetary Fund.

“There is still no guarantee that such gestures could affect Iran’s calculus in Iraq, which is managed by the Quds Force. But it is worth a try.”

C. Anthony Pfaff, nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Iraq Initiative:

“The current tit for tat between US forces and Iran-backed militias is unsustainable. With every exchange of fire, Kita’ib Hizballah (KH) is able to mobilize elements of the Iraqi population to demonstrate against the US presence. Not responding, of course, is equally untenable. The United States does not have a long tradition of placing troops in harm’s way and not permitting them to defend themselves. Of course, the right answer is that the Iraqi Security Forces fulfill their responsibility to protect US forces. However, it is hard to blame them for not having the stomach do so. Iran-backed militias are not only often better armed, but any military action against them will simply energize a brutal, and very personal, campaign directed at individuals and their families who take action against them, much as they did in the early days of the US occupation.

“The only other alternative is for US forces to leave. While US forces would eventually draw down anyway, doing so under pressure from Iran will put the entire US-Iraq relationship in jeopardy. It will make little sense for US politicians of any party to continue investing not just money, but time, expertise, and other resources to a government that has sided with an adversary. Should that happen, the Iranian victory will be complete. However, that victory will come at a huge cost to Iraq, as Iran has little to offer it but exploitive economic arrangements and thugs to keep the population in line.

“Perhaps worse, such a result will come at huge cost to the region. A US military and political withdrawal almost ensures Iran will use Iraq as a platform to expand its influence in the region. Should that expansion include attacks on critical infrastructure in places like Saudi Arabia, tensions will flare and violence will escalate. Should that escalation lead to a wider conflict, Iraq will find itself on the losing side of a very messy war with few partners willing to assist in its considerable recovery needs.

“The nomination of Adnan al Zurfi, however, points a way out of the current impasse. Unlike the previous Iran-backed nominees, who generated massive popular protests, Zurfi has so far not done so. It is, of course, unlikely his proposed cabinet will fare any better than Muhammad Tawfiq Allawi’s, unless he can make his nomination attractive to the Iran-backed parties. However, the relative quiet regarding his nomination suggests that Iraqis may not be as ready to be done with the United States as the members of the Fatih Party suggest.

“The point here is the United States has room to maneuver, the question is how. First, the United States needs a better job of engaging the narrative in a way that builds trust. A critical component of the current narrative is that while the United States claims to have evidence that KH is behind these attacks, it refuses to share that evidence. Not presenting a public case does not help the US cause and only feeds accusations that the United States is expanding its conflict with Iran into Iraq.

“Second, the United States needs to leverage its influence with the Iraqi government, which it consistently underestimates, to find a way to contain the militias. The United States does not need the Iraqi Security Forces to take KH, or its Islamic Republican Guard backers, on directly. But it does need the Iraqi government to do more to shape their choices. Doing so is not unprecedented. In 2009, the United States came to an accommodation with Shia militias that led to a ceasefire in exchange for withdrawing its combat forces by the end of 2011. The United States and its Iraqi partners need to find new lines. These lines will necessarily benefit the militias; however, if it incentivizes them to abandon their current attacks, it will distance them—at least a little—from Iran’s objective of driving the United States out of Iraq. Such an accommodation will not lead to peace; however, any ceasefire will buy time for the nomination of a new prime minister as well as his efforts to get Iraq to early elections.

“At these elections, Iraqis will again have the opportunity to decide their future, including their relations with the United States and Iran. Should the tit-for-tat continue that long, it is likely Iran will come out the winner. However, if the United States can find a constructive, alternative way forward—one that forces these militias, and the political parties that back them, to choose between votes and supporting Iran’s objectives, the United States—and Iraq—will be the winners.”

David Mack, nonresident senior fellow in the Atlantic Council’s Middle East Programs:

“Pressure on US military forces by Iranian proxies continues, and US responses have not ended the problem. Strategists in Tehran anticipate that further loss of American lives might force a humiliating withdrawal from Iraq. Faced with internal health and economic disasters, Iranian leaders could at least claim a geostrategic victory over the ‘Great Satan’ and those Iraqis who lean toward Washington. Most Iraqis want productive relations with Washington but cannot bear a confrontation with their neighbor, particularly in the middle of government collapse with no clear successor prime minister to manage the balance between the partner they want and the neighbor they must live with.

“The specter of resurgent ISIS terrorism is an existential threat to Iraq, a serious threat to Iran, and a significant threat to US objectives not only in Iraq and Syria, but in the Greater Middle East. Key partners like Saudi Arabia, Israel, Turkey, and Egypt are watching how we manage relations with Iraq. It is a terrible place for the United States to pursue maximum strategic pressure on Iran, but it can become a bulwark against renewed terrorism. Over the longer term, Iraq can also become a better model than the one favored by hardline Iranian leaders.”

Thomas S. Warrick, nonresident senior fellow with the Rafik Hariri Center and Middle East Programs at the Atlantic Council:

“For all that life in the United States and around the world has changed because of COVID-19, three things have not changed—yet they should. The governments of Iran and the United States are both determined to continue applying maximum pressure to the other. Iraq continues to avoid fundamental reforms that many Iraqi politicians seem determined to resist. Unthinkable though it is today—as the world pauses for social distancing—these factors are building to a crisis later this spring or summer that could drive COVID-19 off the front pages.

“Iran was undeterred by the death of IRGC Quds Force head Qasem Soleimani in early January. Iran no longer makes a secret of its strategic goal to drive the United States out of Iraq and the Middle East. After Iran tried to get its supporters in the Iraqi parliament to force Adil Abdul-Mahdi’s caretaker government to expel the United States, it has reverted to using its militia proxies to attack US bases and facilities. Expect attacks to increase, and if they result in significant American deaths, President Trump will be compelled by a mix of motives to retaliate with strikes against targets in Iran. Despite Iran being one of the countries most affected by COVID-19, Iran shows no interest in reaching an accommodation with the United States or its Arab Gulf neighbors.

“The United States seems unmoved by the humanitarian crisis in Iran to offer a serious gesture in response. The United States imposed additional sanctions on March 17. President Trump supposedly decided not to attack targets in Iran as a gesture, but it’s doubtful Iran saw this as charity. When The Department of State’s senior Iran policy official Brian Hook was asked on March 19 whether the United States was thinking about offering sanctions relief to Iran to help it deal with the COVID-19 crisis, he called the idea a “tired regime talking point.” Some Trump administration officials see Iran’s response as further proof that maximum pressure sanctions will succeed eventually in forcing a change in regime behavior, if not also a change of regime. The Trump administration is showing no signs of wanting to change policy.

“The Iraqi government is still trying to find a prime minister able to win an absolute majority in the Council of Representatives, Iran’s parliament. The latest nominee, Adnan al-Zurfi is a colorful Iraqi politician who was formerly governor of Najaf. (American political experts: think Edwin Edwards.) Al-Zurfi strongly opposes the independence of the Iranian-backed militias, who oppose his candidacy. With the parliament unwilling to approve Iran’s choices, and Iran able to block the nomination of those who want to bring its militias under Iraqi government control, none of Iraq’s serious problems are being addressed. Thus far, Iraq hasn’t been able to bring the Iranian-backed militias under government control, and thereby end the attacks on US forces, but neither can Iran force the United States to leave Iraq absent a decision by President Trump to order a humiliating withdrawal.

“Despite the volume of virtual ink outside experts have devoted to offering helpful ideas, it’s hard to see any of the prescriptions offered as persuading Iran, Iraq, or the United States to make fundamental changes in how they approach the present crisis. Three things could happen. (1) There is really no such thing as “accidental war,” but in this environment, a lucky (or unlucky) strike by either Iran or the United States could alter the course of history by causing one or more leaders to take actions that lead to war. (2) Absent this, the situation could drift until the November 3 US election, the death of eighty-year old Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, or the upcoming Iraqi election forces one or more governments to reconsider whether to make fundamental changes to their policies. (3) Or the human and economic toll of COVID-19 could eventually force someone to realize that fundamental policy change really is necessary.”

Further reading:

Image: Demonstrators gather as they protest during the International Women's Day in Baghdad, Iraq, March 8, 2020. REUTERS/Thaier Al-Sudani