At the end of 2019, European Central Bank (ECB) forecasts of Euro Area growth and inflation for 2019-20 were downgraded by about ½ point each year, compared to those published at the end of 2018. This was due to some risks which materialized in 2019, for example the trade war with the United States. The current scenario remains tilted downward by persistent risks, whether global or domestic. Therefore, the ECB stance has been made even more accommodative, although monetary policy cannot remain the only game in town.

‘’Anyone who isn’t confused doesn’t really understand the situation.” This statement by the US journalist Edward R. Murrow, who died in 1965, could not apply better than today. We are living times of uncertainty, with trade or money sailing in unchartered waters, to quote two examples. Nonetheless, forecasters try their best to shape a central scenario for major economies while acknowledging for upside and more often downside risks. According to the US economist Frank Knight (1921), risks are uncertain events the impact of which may nevertheless be approximately quantified with some probability. Such risks are not included in the central scenario of projections but acknowledged for, as by the Eurosystem staff (ECB plus nineteen national central banks) who published its revised forecasts in December 2019 (extended to 2022 for the first time).

This post recaps the central scenario for the Euro Area (EA) and the main global and domestic risks surrounding this scenario (even if these risks should not all materialize together in the future).

#1 ECB forecasts for the EA are downgraded by about 1/2 point for 2019-20 to end of 2018

In a nutshell, the table below predicts that both growth and inflation hover hardly above 1% in 2019-20, before returning around 1.5% in 2021-22 (annual average). The revisions compared to the previous forecasts by the ECB alone, dated September 2019, are marginal; but they are significant compared to the same exercise by the Eurosystem published end of 2018. The revisions broadly reduce the forecasts by about ½ point for both growth and inflation in 2019 and 2020, and again for inflation in 2021. Indeed, several risks—perceived last year (but not integrated)—had materialized.

(revision Dec. 2018)

| ANNUAL AVERAGE % CHANGE | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) | 1.2 (-.5) |

1.1 (-.6) |

1.4 (-.1) | 1.5 |

| Harmonized Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) | 1.2 (-.4) |

1.1 (-.6) |

1.4 (-.4) | 1.6 |

| HICP excluding energy & good = core | 1.0 (-.4) |

1.3 (-.3) |

1.4 (-.4) | 1.6 |

For real gross domestic product (GDP), growing again around 1.5% per year presumes a return to potential and, hence, limited pressures on prices. As a result, inflation would be only 1.4% in 2021 (instead of 1.8% forecast end of 2018) and 1.6% in 2022 (first forecast), still far from the official target of “below but close to 2%.” Most of these revisions were already integrated in the previous quarterly releases; they had justified the ECB stimulus announced in September 2019, despite some vocal divergences within its Governing Council on its timing, content, and impact. Integrating the stimulus in this central scenario helps forecasts to be slightly higher in 2021-22 given the delays in the effects of monetary policy.

Let’s turn now to the main risks surrounding this scenario, which globally remains tilted downward.

#2 The longest US economic expansion ever will end one day, but less likely in 2020

At the start of 2020, there hasn’t been a recession (two consecutive negative quarters) for more than ten years. This is longer than ever, with the previous maximum period of expansion observed in 1991-2001. No surprise that Cassandras regularly warn against a recession within twelve months, especially each time the yield curve of the US interest rates inverts.

However, at least two factors alleviate this pessimism or make it look premature:

The recovery since 2010 has been slower than usual with some mini-cycles dampening it, as had in early 2015 for instance. Moreover, the stimulus of the Trump administration has been ‘’tailored’’ to last until the US election (even if it is fading away in 2020); no doubt a recession will occur, although presumably after 2020; it will later affect the EA with the usual delayed impact; this is why such a risk is not integrated in the ECB forecasts through 2022.

All US recessions were preceded by an inversion of the US yield curve, but all inversions were not followed by a recession. Besides, over the last decade, the US yield curve has shifted downward and become flatter. Therefore, an inversion may happen more often and lose any predictive power. Last, the Federal Reserve has preemptively loosened its monetary policy in 2019 and the policy-mix is fully accommodative. Indeed, measures of recessions fears, whether according to the market or models, have had hiccups but, at the start of 2020, they stand lower again.

#3 China is slowing down, possibly more than acknowledged, not only because of the trade war.

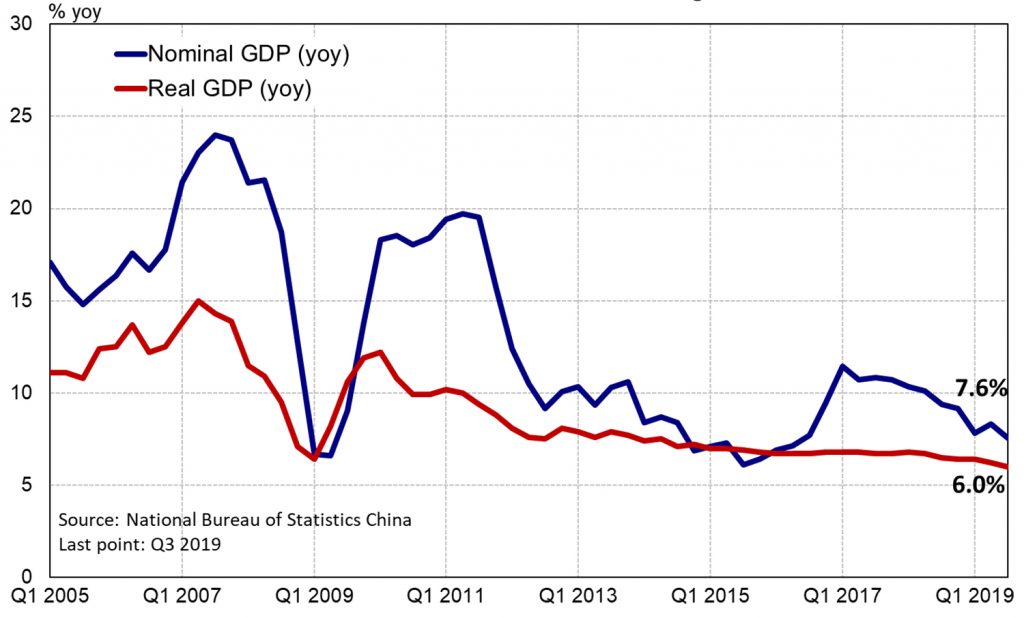

Observed data for China’s real GDP differ rarely from official forecasts, with growth around 6% in 2019, the lowest figure over three decades. Long-term factors play an obvious role: less rural workers (with low productivity gains) are migrating toward urban industries (with higher productivity gains) and there is a parallel shift toward services with intermediate productivity growth. More recent factors are also at play as illustrated in the charts below.

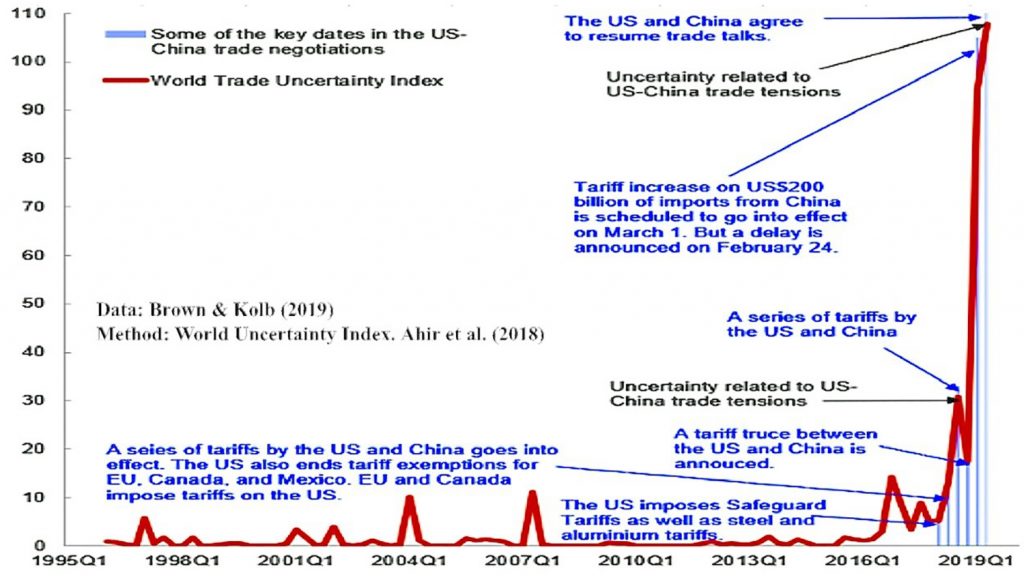

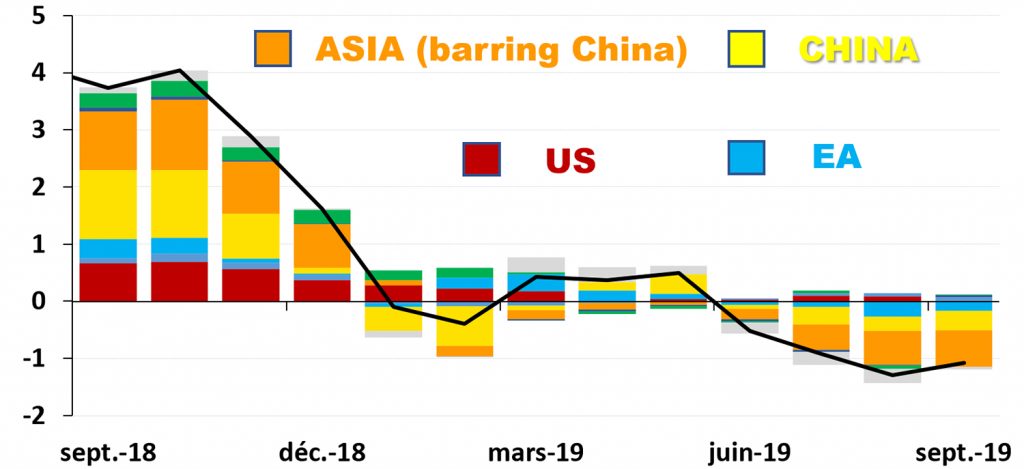

The global ‘’trade uncertainty index’’ (Chart 1a), built by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), is peaking. Higher tariffs and fears of a trade war affect Chinese activity that, of course, matters for the EA and, especially, Germany. Hitherto, global trade has clearly dropped, with a larger contribution from China and the rest of Asia (see Chart 1b). Nevertheless, the impact has been limited for the EA as a whole.

Actually, higher tariffs between the United States and China have had hitherto a limited effect on their bilateral balance of trade in value; and the current account of China is expected to rebound after its recent trough close to equilibrium. The split of value between volume and price is always delayed and somewhat arbitrary. Chart 2 also shows that the growth of the Chinese GDP is much more stable in real terms than in nominal ones. Here as well, the split between price and volume is not always easy to explain and guarantee. True, the GDP deflator inflation has indeed decreased over the last two decades while remaining somewhat volatile. However, this split favors, more and more, both the stability and the magnitude of volumes to the detriment of prices. The slowing down of the Chinese economy is thus progressive, lasting and possibly…underestimated.

Some damages have thus materialized in 2019 but there are also regular prospects of trade truce.

#4 High/increasing debt over GDP is sustainable only thanks to exceptionally low rates.

Beyond geopolitical tensions (such as between the United States and Iran and potential effects on the price of oil), other risks persist such as the extent of the India’s slowdown, as large as that of 2016 (demonetization), or Brexit which is now confirmed but remains very uncertain in terms of content; yet, such shocks are mainly asymmetric, affecting a lot less the EA and, hence, not developed here.

More puzzling are global finances and especially high or increasing debt/GDP ratios. Admittedly, in mature economies, the ratio of total debt over GDP has globally stabilized around its 2017 level. Moreover, the latter level is below that of 2007, because a drop in private debt has offset an increase in public debt. By contrast, in emerging market economies (EMEs), the “total” ratio has approximately doubled from its 2007 level. Public debt over GDP keeps increasing while private debt has just stabilized; nonetheless, in China this stabilization occurs at a very high level for non-financial corporates (more than twice that of mature economies).

In mature economies, extremely low interest rates make high public debt ratios sustainable. When growth exceeds interest rates, one may advise to raise debt so as to finance productive investment. The same currently applies to EMEs with exchange rates pegged to reserve currencies. Yet, financial asset prices may drop from their current peaks with interest rates surging again, especially where fundamentals are weaker and markets shallower or more prone to bubbles. Such a risk looms over the global economy but less directly over the EA, if only because it issues debt in its own currency.

#5 EA-specific risks seem also lower, although they are still more tilted downward than upward

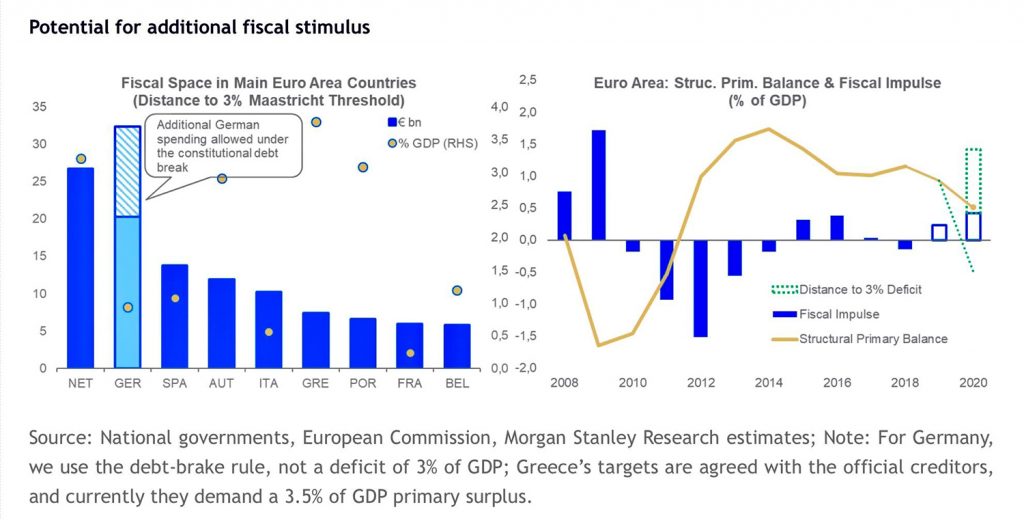

In 2019, the EA structural primary balance should be lower than in 2018 (possibly the lowest since 2012, see Chart 3) and slightly less than in the Eurosystem forecasts one year ago. A fiscal stimulus was then perceived as a positive risk but could not be integrated in the central scenario of end of 2018, which conventionally relies on voted public finances. Here again, the risk perceived in 2018 (upward this time) has materialized even if less than some wished, given the fiscal space of a few surplus countries, especially Germany. Similarly, the central scenario of end of 2019 includes a more accommodative fiscal stance and a residual upward risk of fiscal stimulus. This holds even if political authorities, for example in Germany, do not easily agree on, or acknowledge a further possible impulse.

By contrast and before turning to persisting downside risks, let’s also note that some negative risks looming last year have not materialized. As an example, for the EA at least, neither the threat of higher tariffs nor some US presidential statements have resulted in a currency war. Globally, the volatility of exchange rates is now very low and, in particular, the Euro-US Dollar bilateral rate and the Nominal Effective Exchange Rate for the EA have traded in a remarkably narrow range in 2019 (±1%).

More worrisome than a possible contagion to services of recent lows in manufacturing remains a risk of de-anchoring of inflation expectations. Such a de-anchoring would be dangerous in case of an adverse shock even if the ECB has been able to avoid any deflationary spiral since 2012. But despite its very active monetary policy, inflations expectations have not rebounded for very long when measured for instance via Indexed Linked Swaps (ILS). Possibly too much focus has been put on such market expectations since ECB President Mario Draghi drew attention to their collapse in August 2014. Indeed, expectations of inflation for five years in five years are at times somewhat irrationally correlated to gyrations in the spot price of oil. Moreover, let’s acknowledge that even in the United States where inflation is closer to 2%, ILS expectations of inflation remain volatile and low.

Conclusion

To sum up, after the high real growth of the EA in 2015 (averaging slightly more than 2% per year), growth in 2019-20 has been downgraded as several risks materialized. Furthermore, the balance of persistent global or domestic risks remain negative even if less than last year. In addition, core inflation has hardly picked up after the Great Recession. Possibly because of backward-looking expectations, inflation forecasts (whether headline or core) are still well below the 2% target at the 2022 horizon. This holds although more and more authorities have said that this target should officially become symmetrical so as to raise expectations. The ECB strategic review due at the end of 2020 will tell us more about that. In the meantime, no surprise if ECB rates remain low for longer.

There are, of course, other deeper question marks surrounding economic forecasts, such as the challenges of climate change and whether we are stuck in “Secular Stagnation” or only at the start of the “Digital Revolution.” While these matter for monetary policy, dealing with them goes well beyond the realm of central banks which cannot remain the only game in town.

Marc-Olivier Strauss-Kahn is a nonresident senior fellow in the Atlantic Council’s Global Business and Economics Program. He is also honorary director general, Banque de France (BDF), and adjunct professor at ESSEC and ESCP Business Schools. The views expressed here do not commit the BDF.

Further reading:

Image: Share traders start their trading systems at the start of the trading session the day after the Brexit deal vote of the British parliament at the stock exchange in Frankfurt, Germany, January 16, 2019. REUTERS/Kai Pfaffenbach