In April 2023, many foreign observers found themselves startled when senior diplomats from Iran and Saudi Arabia met at a China-brokered summit in Beijing—the first high-level meeting between both inveterate foes in several years. Beijing appeared to demonstrate a new diplomatic prowess—an active willingness to mediate tensions in one of the most geopolitically challenging and conflict-ridden portions of the globe.

In a highly deteriorated security context in the Middle East, the months since have shed light on the Chinese modus operandi in its pursuit of strategic goals in the region. China’s muted response to the Houthis’ attacks in the Red Sea reveals that China is doing what it has long done. That is, Beijing is freeriding on US and European security guarantees to enhance its own presence and influence in the Gulf and the northwestern Indian Ocean. It is reaping benefits and advancing its own goals, while others carry the engagement and reputational costs of securing sea lanes. In response, the United States and its allies and partners, which are shouldering these costs, must find ways to better manage China’s freeriding and opportunism in the region.

China’s strategy of seeking equilibrium in the Middle East is off balance

In recent years, Beijing has sought to quietly consolidate relations in the Gulf, all without finding itself ensnared in deadly regional antagonisms. It pursues this objective primarily by focusing on political and economic ties while steering away from crises. This means that China will not engage in regional maritime security if it implies a confrontational posture against Iran’s proxies and partners. Rather, its bystander attitude allows Beijing to lay the groundwork for future influence in the region.

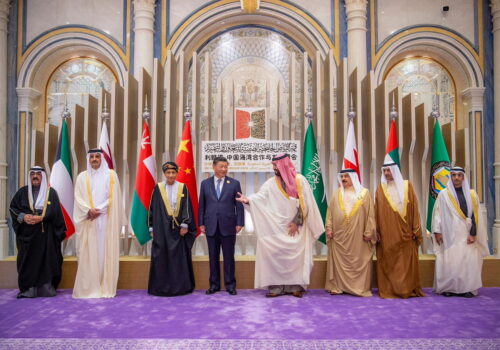

The risk of China’s ambiguous and multi-vector Middle Eastern diplomacy unraveling has been well managed so far. In a perpetual quest for equilibrium, when Beijing raises engagement on one side of a rival relationship, it complements its efforts with equivalent engagement with the other party. In 2021, China signed a twenty-five-year partnership agreement with Iran, without raising issues about its bilateral relations with Saudi Arabia. When Chinese leader Xi Jinping visited Saudi Arabia in 2022, bilateral relations were elevated to the same partnership status as Iran. Similarly, China has been supporting Palestine’s independence and calls for a return to 1967 borders, even as Israel has become China’s main economic partner in the Levant region, with which it prioritizes technology and innovation.

On the surface, Beijing seeks to showcase an ability beyond that of a bystander—to speak to various stakeholders as regional actors harden their postures against Western countries. This strategy is now being challenged. While support for Palestine and focus on the Arab League remains consistent with previous policies, the abrupt degradation of its relationship with Israel is bringing China to the inherent limits of this quest for equilibrium.

At the outset, the Chinese Communist Party’s refusal to blame Hamas for the October 7, 2023, attacks were widely criticized by Israel, which perceives the Palestinian movement as an existential threat. Moving away from previous statements, Chinese foreign policy officials have overtly criticized Israel and Chinese official media amplification of anti-Semitic discourse could even be characterized as a form of state-sponsored anti-Semitism. The recent Israeli discovery of Hamas’s supplies of high-tech Chinese weaponry will definitively wound China’s relationship with Israel, especially if direct involvement is proven.

Moreover, the plans China has proposed are quickly revealed as neither credible nor actionable. Last year, China positioned itself as a mediator between Saudi Arabia and Iran, while both countries were already seeking deconfliction. The tripartite committee reconvened in Beijing on December 15 with no tangible results in stopping the Houthis’ attacks in the Red Sea. Similarly, regarding Israel-Palestine, Beijing updated its four-point proposal from 2021 to a very similar five-point position paper, both almost non-actionable politically.

The Red Sea shipping crisis is China’s opportunity to leverage its strategic immunity

As the United States and European countries continue to take on maritime security risks, their contribution is a double-edged sword for China.

On one side, it is in China’s interest to let US and European forces deter the possibility of a larger conflict between Israel and Iran or a regional conflict that could possibly spillover from the war in Gaza, disturbing Chinese container flows in the Red Sea and through Suez. It is particularly important at a time of slower growth in China for it to continue to export goods through the Suez route to Europe and the United States. In particular, Chinese companies had planned to exploit a transitory boom in its electric vehicle exports to Europe before the markets close as Europeans develop their own production capabilities in-house.

So far, Houthi attacks have not targeted Chinese shipping, seemingly benefitting from a form of strategic immunity gained in the region over recent years by freeriding on third country security guarantees. Some ships have used their signals to show they have links to China as a measure to avoid attacks by militants. The apparent Chinese immunity from Houthi attacks lowers the costs of insurance, creating yet another form of unfair market distortion.

The People’s Liberation Army boasts that its navy “continues standard operations” in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden, according to Chinese media. Communication centers around Chinese non-involvement to contribute to the posture of immunity. Beijing’s rhetoric is aimed at preparing to lay the blame for any ongoing or future shortcomings in the region on the West and in particular the United States, especially since the United States’ and United Kingdom’s military retaliation against Houthi infrastructure in Yemen. China also seems to try to portray a wedge between Europe and the United States, despite their coordination in Operation Prosperity Guardian.

On the other side, US and European military assets in the Gulf could be perceived as a potential threat to China’s own shipping, were Sino-US ties to deteriorate even further. It highlights the vulnerability of its growing presence to future interdiction. As a consequence, the Chinese military strategy toward the Arabian Gulf is aimed at counterbalancing against this issue. This led to the creation of its first oversea base in Djibouti in 2017 and a permanent naval presence in Aden since 2008. Boosting the Chinese navy’s surveillance capabilities, as well as its ability to operate and act over strategic sea lanes to mitigate the risk of blockade, is deemed essential to preparation for any potential large-scale Sino-US conflict in the Indo-Pacific. Over the past few years, Chinese companies have multiplied their investments in critical infrastructure around the Suez Canal as well as on both sides of the Red Sea.

Calling out China for its freeriding and opportunism

Ongoing freedom of navigation and maritime security initiatives must find a way of managing China’s freeriding and opportunism, starting with debunking Chinese disinformation, a strategic communication calling out Chinese behavior, and better explaining US and European contributions.

Letting the current situation endure only lays the groundwork for future Chinese influence in the region and the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) establishing a more diplomatically legitimate naval presence cost-free. For example, since 2008, China has used the involvement of the PLAN in cooperation with European Operation ATALANTA (aimed at protecting World Food Programme ships sailing to and off the coast of Somalia) to establish diplomatic alignments and conduct military diplomacy.

Given the major implications of a partial closure of Suez for its economy, China should be pressed to share the political responsibility for persuading regional actors, and Iran, as it has apparently tried to showcase, but also help harness a regional escalation. The existing channels with European nations—the United Kingdom and France in particular—as well as the recent resumption of military-to-military talks with the United States are an opportunity to continue to push against freeriding and engage with China on issues other than its direct regional environment. They should also serve as a channel for Europe and the United States to signal to China the costs of any potential collusion with Iran’s proxies and partners.

Implications in the Indo-Pacific

China’s behavior in the Red Sea also impacts larger problems for maritime security in the Indian Ocean. An obstruction of the primary international maritime trade route between Asia and Europe going through the Suez Canal and the Bab-El-Mandeb Strait only serves to further highlight the importance of alternative trade routes, which also constitute secondary access to the Indo-Pacific theater.

Since the latest round of Houthi attacks began in the Red Sea, some companies have diverted their shipping through the Mozambique Channel and around the Cape of Good Hope instead, even though it adds to the duration and cost of the journey. Moreover, with an Asia-Europe transatlantic route through the Panama Canal shrinking due to water scarcity, Good Hope could be the lesser of two evils for shipping companies for an undetermined period.

Lessons learned from China’s posture and modus operandi in the northwestern Indian Ocean should therefore be applied to the Mozambique Channel and the Gulf of Guinea, pointing at the need to coordinate Indian Ocean and Africa strategies. France, with oversea territories in the Mozambique Channel (Mayotte, Scattered Islands) and in the southern part of the Indian Ocean (La Réunion), can play a critical role in coordinating these strategies.

The French vision of the Indo-Pacific includes securing this secondary route, which is also affected by power competition, illegal trafficking, and jihadi movements which could also evolve to become maritime threats. The crisis can provide a canvas for Europe, the United States, and regional partners to lay the groundwork for a common understanding of what a crisis spill-over on important sea lanes in the Indian Ocean could look like.

Léonie Allard is a visiting fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Europe Center.

Further reading

Thu, Feb 1, 2024

China doesn’t have as much leverage in the Middle East as one thinks—at least when it comes to Iran

MENASource By Jonathan Fulton

China is more likely to continue to be the regional actor it has been over the past decade—one that comes to the Middle East to trade and build, not lead.

Thu, Jan 25, 2024

Houthi attacks in the Red Sea hurt global trade and slow the energy transition

New Atlanticist By William Tobin, Joseph Webster

Recent attacks on commercial shipping in the Red Sea are a reminder that a major disruption to freedom of navigation would hold many negative consequences.

Thu, Feb 8, 2024

Houthi attacks on ships in the Red Sea add to Egypt’s economic troubles

MENASource By Shahira Amin

The decline in Suez Canal revenues has put further strain on Egypt's already faltering economy at a time when the country faces a severe foreign currency shortage.

Image: Soldiers of the Chinese People's Liberation Army (PLA) Navy take part in a ceremony as a replenishment ship sets sail to the Gulf of Aden and the waters off Somalia, from a naval port in Qingdao, Shandong province, China September 3, 2020. Picture taken September 3, 2020.