China stands to gain from a weakened Russia. The West should prepare now.

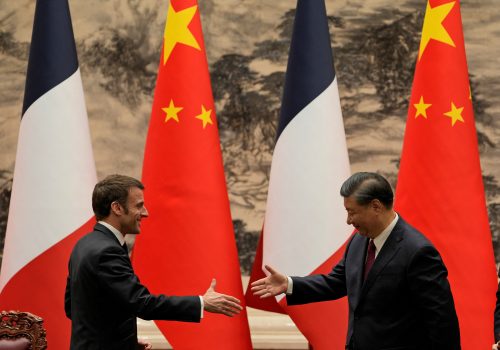

As the war in Ukraine enters yet another phase with the coming Ukrainian offensive, it is clear that China is positioning itself to benefit from the outcome regardless of which side ultimately prevails. China has already been able to pocket significant gains in its relations with Russia as Moscow has grown more dependent on Beijing for its economic survival and for political support. China also has gained ground in its relations with the European Union, especially with Germany and France, which appear to have recognized Beijing’s growing role in shaping relations between Kyiv and Moscow. Although there is no consensus in Europe on relations with China going forward, the series of recent high-level visits to China by German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, French President Emmanuel Macron, President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen, and German Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock have driven the point home that, though geographically distant, China is increasingly a power in Europe.

How China has stood to benefit from Russia’s war has changed over the last year and a half. In early February 2022, Russian President Vladimir Putin and Chinese leader Xi Jinping met shortly before Russian forces launched their full-scale invasion of Ukraine. If Putin divulged his plans then, Xi evidently did not dissuade him from launching the brutal attack. The joint statement coming out of this meeting proclaimed a “no limits” partnership. Had Russia succeeded in its initial invasion and taken Kyiv in the first days, the rules-based international order would have been weakened. Having extended support to Ukraine for so long, the United States and its allies and partners would have had their commitments called into question. Autocratic might would have won the day. All of this, of course, would have been music to Xi’s ears, and all without Beijing firing a shot.

How Beijing benefits now

Today, it’s a different story, but China nonetheless stands to benefit. A protracted war of attrition in Ukraine serves Beijing’s interests in that it will lead to the long-term weakening of Russia, thereby fundamentally shifting the Sino-Russian power balance decisively in China’s favor for years to come. China is also benefitting from cheap Russian energy, which is supporting its economy and improving China’s competitive position in world markets. Measured by value, Russia’s pipeline gas exports to China increased two-and-a-half times in 2022, while its liquefied natural gas exports to China more than doubled. Last year China also increased its volumes of Russian coal by 20 percent.

In addition to energy, China stands to benefits from the realignment of Russia’s priorities caused by its invasion of Ukraine in the area of military modernization. The biggest prize over the horizon for Beijing is negotiating with Moscow for access to its advanced military technology, especially attack submarine propulsion systems, where China is significantly behind Russia and the West. This also applies to several other Russian weapon systems, including hypersonic missile technology, whereby the past three decades of access to Western technology have allowed Moscow to build upon and improve Soviet-era systems.

Much of the debate across the West today concerns the end state in Ukraine, but very little about potential end states in Russia, which for China remains a core question. Putin’s folly of invading Ukraine has all but guaranteed that Russia will emerge from the conflict enfeebled and diminished in its relative power position in Eurasia and globally. History has shown that Russian wars fought outside the national territory tend to generate powerful centrifugal forces at home, leading to internal turmoil, as was the case in the aftermath of the Russo-Japanese war of 1904 and the defeat of tsarist armies in 1917. Either Putin or his eventual successor could look to Beijing for support as he contended with domestic strife. China would then be in a position to condition its support on fealty to Beijing.

There is another option, the chances of which are small but not zero. Defeat in a major foreign war might in extremis lead to the fracturing of the Russian state, as happened following the Soviet war in Afghanistan, which saw the USSR implode two years after the Soviet troop withdrawal. Here, too, Beijing stands to benefit if Russia’s central and eastern parts then becoming subject to Chinese predation for resources, vassalization, or—as unlikely as it might seem now—even colonization.

At the Twentieth National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party that secured an unprecedented third term for Xi as China’s top leader, he articulated his goal of “build[ing] China into a great modern socialist country that leads the world in terms of composite national strength and international influence by the middle of the century.” In geopolitical terms, vassalization of Russia and a takeover of Taiwan are important stepping stones to this goal. China could get there if it vassalizes the Russian Federation, while also keeping Europe tied to its market, thereby isolating the United States and effectively excluding it from Eurasia. Beijing may even see a pressing need to send more of its military to its northern border, and potentially beyond, since the immediate effects of Russian fragmentation would assuredly threaten its access to energy and food. Should Russia fragment, it would be geostrategically transformative, midwifing a structural great-power realignment on a scale the likes of which the world has not seen for three centuries. It would create a true Chinese “empire of the middle” whose combined power would eclipse what the United States and its democratic allies could bring to bear.

Why Ukraine must win

There is a scenario in which China does not stand to gain from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, at least not beyond what it has already accrued. First, the West must rearm, with Europe restoring its military capabilities in NATO to provide the bulk of conventional deterrence and defense in Europe, with the United States providing the nuclear umbrella and high-end enablers. Europe’s rearmament in NATO is sine qua non to peace on the continent, while also increasing the overall military power of democracies worldwide and discouraging aggressors from challenging the existing order. Equally important, this scenario hinges on Ukraine successfully defending itself and reestablishing national control over its territory within the borders of 1991.

Ukraine’s victory would reaffirm the core principle after 1945 that borders cannot be changed by force. It would show that the West has the staying power to defend the existing international order, sending a clear message to both Moscow and Beijing. It would also be transformative for Eastern Europe, with the example of a rebuilt and democratic Ukraine possibly pulling Belarus out of Russia’s orbit. Ukraine can win. Ukrainian forces can push back Russia’s invasion with more weapons and aid from the West. At the same time, the United States should work with its allies and partners to push back against Chinese aggression in the Indo-Pacific and beyond.

Andrew A. Michta is Dean of the College of International and Security Studies at the George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies in Garmisch, Germany and a Nonresident Senior Fellow at the Scowcroft Strategy Initiative in the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security.

The opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies, the US Department of Defense, or the US government.

Further reading

Tue, May 30, 2023

China is trading more with Russia—but so are many US allies and partners

New Atlanticist By Josh Lipsky, Niels Graham

A number of countries have increased their trade with Russia since its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in early 2022, including non-aligned countries and even some EU members.

Sun, May 21, 2023

G7 triumphs and the debt ceiling quagmire provide a glimpse into competing futures for US global leadership

Inflection Points By Frederick Kempe

A strong performance at the G7, juxtaposed with the United States' debt ceiling drama, highlights the challenges facing US international leadership.

Tue, May 16, 2023

State of the Order: Assessing April 2023

Blog Post By

The State of the Order breaks down the month's most important events impacting the democratic world order.

Image: Russian President Vladimir Putin and Chinese President Xi Jinping attend a welcome ceremony before Russia - China talks in narrow format at the Kremlin in Moscow, Russia March 21, 2023.