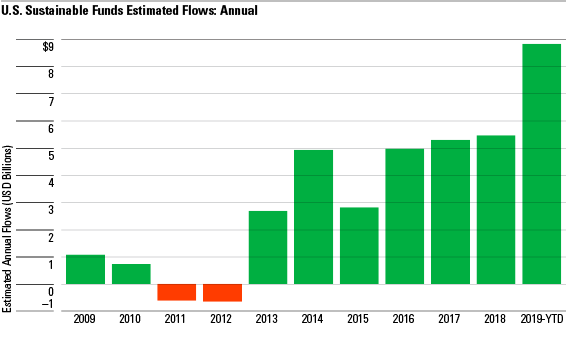

Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) has been designated the most significant investment trend of a generation. With just over $30 trillion dollars invested in sustainable assets across five major markets, “ESG,” “sustainable,” “impact,” and “socially responsible investing” have become a truly a global phenomenon. Even amidst the uncertainty of the US-China trade war, US investment has continued to pour into sustainable-focused funds, marking record high allocations through June 2019 (see in Figure 1).

Within the ESG acronym, the environmental component garners the most investor attention by far. Rockstar central bankers and some of the world’s most powerful business leaders have led the charge for a task force on climate disclosure embedded within the Financial Stability Board. Indeed, while the European Central Bank continues to monitor the ways in which climate change impacts monetary policy, the German government—purveyor of one of the world’s preferred flights to safety in the form of a bond—has mulled over options for a debut green-bond sale. Similarly, French, Korean, and Chinese companies have issued some of the largest green corporate bonds. And as the world’s third largest equity market, Hong Kong, is stepping up its requirements for disclosure on ESG and green funds, as London is potentially following suit.

Looking beyond liquid markets to private capital and direct investing, the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund, well-known for its vigorous stance on divesting from carbon-related assets, has opened the door to future deployment of capital into unlisted infrastructure projects, but only those related to renewable energy. Even major oil producers with an eye on the future continue to invest in renewable energy projects and emerging technologies such as carbon capture. Meanwhile, as customers and countries alike are increasingly adopting an activist stance against plastics, some of the world’s largest consumer product companies are developing biodegradable packaging options in an effort to assuage the concerns of their customers.

In spite of the sea change of capital commitments, the changing tack of investment strategy, and the development of products to meet consumer demand, is the green gold rush just a fleeting fancy of millennials destined to give way to the next shiny trend on the horizon? Remember fair trade? Is climate investing actually sustainable?

Climate change and economics

The debates on climate change are as polarizing and fractious as those between protectionism and free trade. For some, climate change is a petty hoax. For others, the world is quite literally melting down, and they believe there is precious little we can do about it.

As Nobel laureate Bill Nordhaus points out, temperatures have risen dramatically within the last century—far more than any other century. Fossil fuels for heavy industry, manufacturing, and transport yield carbon emissions and hence higher concentrations of CO2. And higher levels of CO2 generate a greenhouse effect, which creates a warming process for the earth. The relatively recent and exponential rise in the temperature of the Greenland ice sheet illustrates the extent to which warming is somewhat of a contemporary phenomenon.

But we also must consider the relationship between climate change and economics—and in turn, business and investing opportunities resulting from climate change. We are in the throes of a historical shift in perception: from a world unquestioningly using fossil fuels to power successive industrial revolutions, to a world distressed about rising CO2 concentrations causing economic catastrophe. While carbon emissions may have unlocked GDP growth, we have reached a point at which future economic growth might be harmed by climate change.

The rising sea levels near major coastal cities, increasing hurricane frequency and intensity, rising land temperatures, and ocean acidification—the hallmarks of a warming and polluted planet—will have disastrous economic consequences. Nordhaus, author of The Climate Casino: Risk, Uncertainty, and Economics for a Warming World, looks to three approaches for dealing with these issues:

- Adaptation: such as building high sea walls to protect against rising sea levels and altering hurricanes

- Geo-engineering: attempts to manipulate the earth’s temperature, favored by some for being low cost

- Mitigation: attempting to halt, reduce, or reverse global warming

Mitigating the downside effects of climate change presents rather steep challenges. In our age of instant gratification, policies that may take years to implement, and may only pay off for future generations, can be a hard sell. In terms of investment, deploying vast amounts of upfront capital—whether public, corporate, or individual—in order to arrest downside impacts that may or may not manifest in our lifetime is just a bridge too far for some. Similarly, it may be psychologically difficult to accept that the best globally-coordinated mitigation efforts might only be able to slow global warming rather than stop it all together. If we can’t have it all—and we risk undesirable consequences in spite of expensive actions—why bother?

Greening around the globe

185 countries of the original 197 signatories have ratified the UN-led Paris Agreement, which was a global commitment to contain the rise of the earth’s temperature to two degrees Celsius—or pre-industrial levels—in this century. At the country level, China remains the world’s largest market for renewable energy investing. Beijing has recently pivoted away from investing directly to initiating competitive bids for solar and wind projects, an approach that is likely to lead to lower costs and better performance for investors. Similarly, India is now investing more in solar energy than in coal, as a result of plummeting costs of solar power generation. Renewable energy investment in Japan has increased 3% year on year, climbing to $8.7 billion dollars. And in the Middle East, the United Arab Emirates is moving away from its prowess in producing oil and natural gas and is now developing the largest solar plant in the world in collaboration with the Japanese and Chinese private sectors.

While Europe remains the springboard for all things ESG, recent results for reducing emissions have been mixed. Portugal and Bulgaria now lead the charge. But, for cash-strapped and debt-laden governments looking to reduce their fiscal deficits, the cost of mitigating climate change has at times been placed on individuals, rather than governments or companies. In the wake of the yellow vest movement, French President Emmanuel Macron was forced to scrap a planned fuel tax, which would have further pinched the declining purchasing power of French households.

In the United States, combating climate change has been a prominent feature of the 2020 presidential election campaigns. Alongside Congresswoman Alexandra Ocasio Cortez’s “Green New Deal,” former Vice President Joe Biden has presented his own plan to achieve net zero carbon emissions by 2050, involving investments from both the public and private sectors, as well as incentivizing techniques such as carbon capture. However, beneath these sanguine grand strategies for the future, climate change policies in the United States remain largely municipal or state-based plays rather than federally initiated. The state of New York has passed a bill to eliminate carbon emissions by 2050, while the city of San Francisco already gets 60% of its power from renewable energy.

Greening corporate and investing strategy

Against this hodgepodge of regulations around the world, companies and investors are taking climate action into their own hands with proactive strategies designed either to assuage the fears of environmentally-minded investors or to appeal to a customer base that extends beyond millennials. Within organizations, the entire ESG agenda is shifting away from corporate social responsibility and investor relations rationales, and moving directly under the remit of the c-suite, including the CEO. This shift is prompting waves of ESG specialist recruitment to significantly beef up in-house expertise, as well as investing in environmental fintech to monitor and inform their own investment selection processes.

While there is a flurry of activity in solar and wind power, one area ripe for investing is energy efficiency. Often called the “fifth fuel,” energy efficiency is a common-sense way of reducing carbon emissions, and it often goes overlooked. Certainly as institutional investors pour into logistics plays supporting the global e-commerce boom, finding energy efficient ways of powering logistics and shipping is a natural multiplier effect for existing investments. In real estate and infrastructure, investing in urban greening and urban forests in densely-populated megacities are likely to curry favor with forward-thinking municipal officials and building tenants.

Natural gas: the bridge fuel?

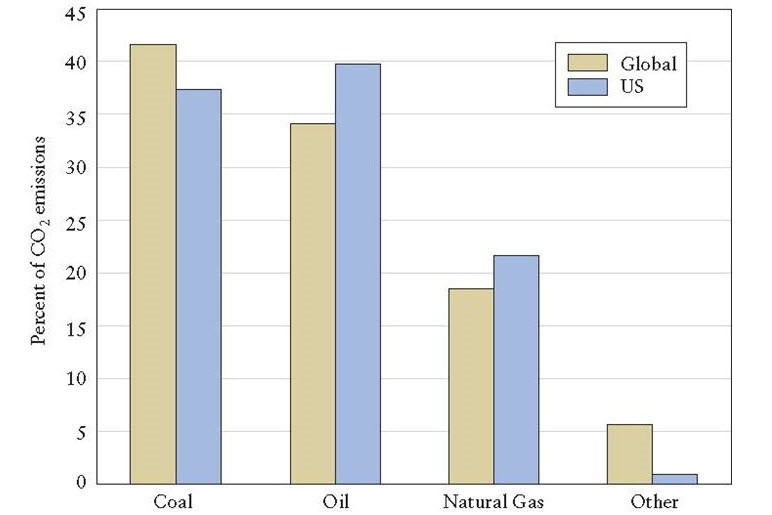

In seeking to meet green investment targets, natural gas could carry us from a polluting past to an ostensibly carbon-free future. As we can see in Figure 2, natural gas burning emits far less carbon dioxide than coal and oil, causing some to brand it as a cheaper and cleaner source to replace coal for power generation and stationary fuel use.

Figure 2: Sources of CO2 emissions, US and Global, 2010.

Source:“Climate Casino,” William Nordhaus

While some investors have carried out a complete and wholesale carbon scrubbing of their portfolios, investing in low-cost natural gas in upstream, midstream, and downstream projects might be a viable choice for the next few decades.

This means that the Middle East—and the Strait of Hormuz—will continue to be an important part of the world; Iran and Qatar hold the world’s second and third largest natural gas reserves with Saudi Arabia and the UAE follow closely behind, and neighboring Israel is joining the ranks of natural gas exporters, with shipments to Egypt scheduled to commence later this year. And as the United States seeks to export its own bountiful reserves—whether to Mexico or Europe— it will also need to play nicely within the global trading system to secure long-term contracts and maintain viable export markets for its products.

Conclusion

Even for the most dubious of investors and climate change hoaxers, the profit potential from the sustainability industry is undeniable. With some of the wealthiest people in the United States applying science to climate change adaptation, and with sturdy inflows into ESG-focused funds—even amidst uncertainty rocking global financial markets—sustainable investing is here to stay. The need for capital is clear: in order to meet the goals set out in the Paris Climate Agreement, the Institute of International Finance estimates that nearly $100 trillion dollars of new investment is required before 2030. Looking beyond the attractive low costs of wind and solar, some prudent investing targets may be the less obvious choices—urban greening, energy efficient logistics platforms, and even natural gas, for example.

The enthusiastic focus on the environment also presents a marketing opportunity that has not yet been fully seized by corporations. While some banks have been accused of greenwashing in peddling their climate wares, some of the world’s leading corporations may still have cold feet in communicating a proactive stance on social issues, and have not yet fully capitalized on the current moment, and have not used their climate policy to get out in front of their customers’ green agenda.

Our great green debate may be viewed in some parts of the world as a luxurious problem. When ministers of finance or energy of developing countries are looking to feed mouths, spur industrial growth, and bring millions of people out of poverty, leapfrogging over coal or oil and moving straight to renewable energy may seem fantastical and simply unfeasible. This is the responsibility component of climate investing. For the institutional investors and policy makers who have successfully implemented environmentally mindful and pro-growth policies at home, the transmission of these policies abroad is absolutely crucial, otherwise the clamoring for ESG is held within an exclusive—albeit environmentally sound—echo chamber, which fails to take root where it may be needed most.

Dr. Alexis Crow is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Global Business and Economics Program and leads the Geopolitical Investing Practice for PricewaterhouseCoopers.

Further reading:

Image: A worker cleans photovoltaic solar panels inside a solar power plant at Raisan village near Gandhinagar, in the western Indian state of Gujarat, February 11, 2014. REUTERS/Amit Dave