Escalating trade tensions pose a severe threat to a transatlantic economy weakened by COVID-19. The coming days will be crucial for the Office of the US Trade Representative (USTR) to decide whether to maximize its rights under the World Trade Organization (WTO) rules or seek de-escalation and avoid hitting a US economy that is already on its knees. On July 26, USTR concluded its most recent public comment period in the long running Airbus–Boeing civil aircraft dispute with $3.1 billion of additional European products under the threat of tariffs. An October 2019 WTO ruling that European Union (EU) subsidies for Airbus violated the organization’s rules authorized the US government to impose up to 100 percent tariffs on $7.5 billion of European exports to the United States.

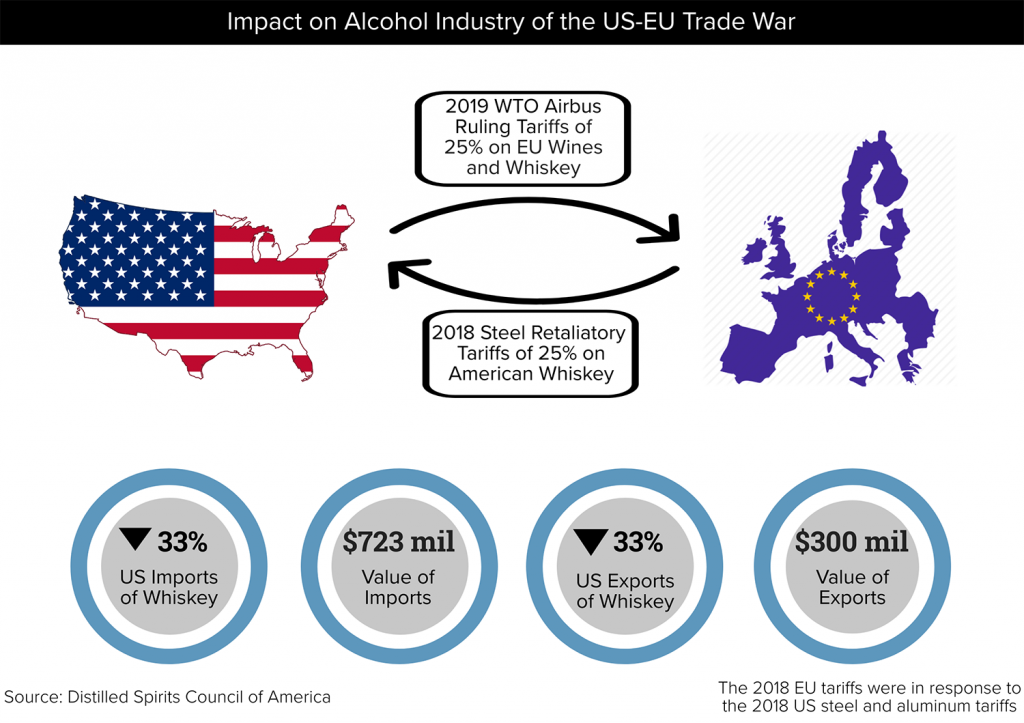

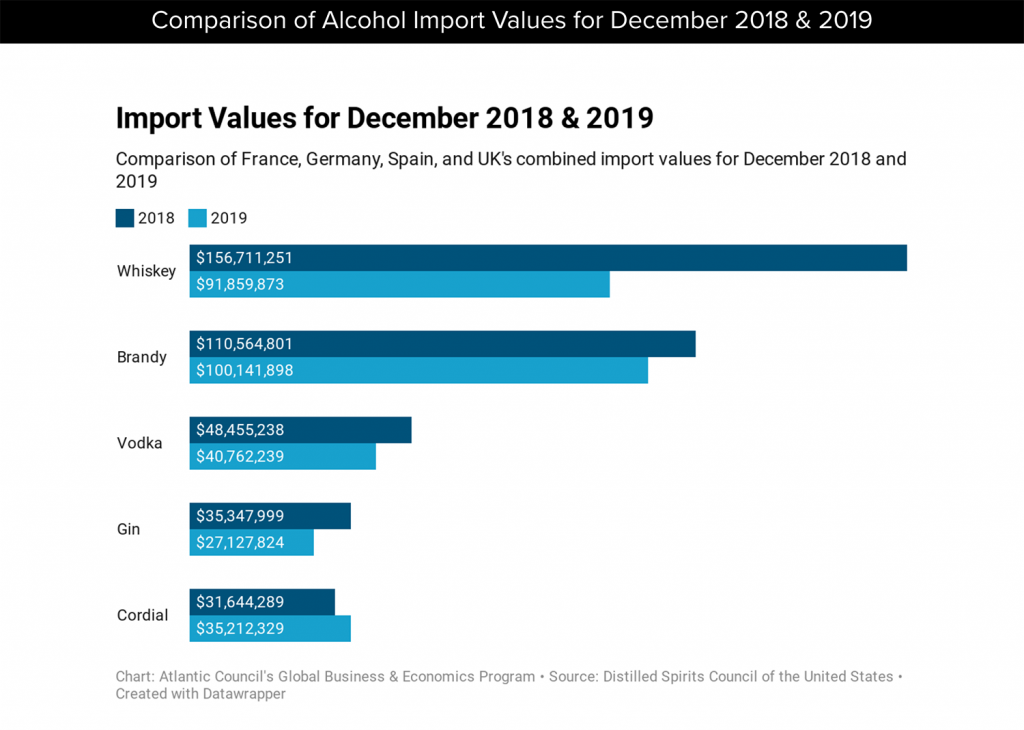

Instead of imposing additional tariffs now, the Trump administration should attempt to ease the trade tensions with the EU ahead of the WTO’s ruling this fall on illegal subsidies for Boeing, which will likely entitle the European Commission to impose tariffs on a similar magnitude of US products. In response to any US decision, the European Commission should prioritize shielding the fragile European economy from further harm over retaliating with tariffs to improve its bargaining position vis-à-vis the United States ahead of the WTO’s Boeing ruling. The US tariffs, which focus on Airbus aircraft but also European agricultural goods such as French wine and British whiskey, have hit small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) on both sides of the Atlantic. A new round of tariffs could push many small US companies over the brink as they are facing an existential threat due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

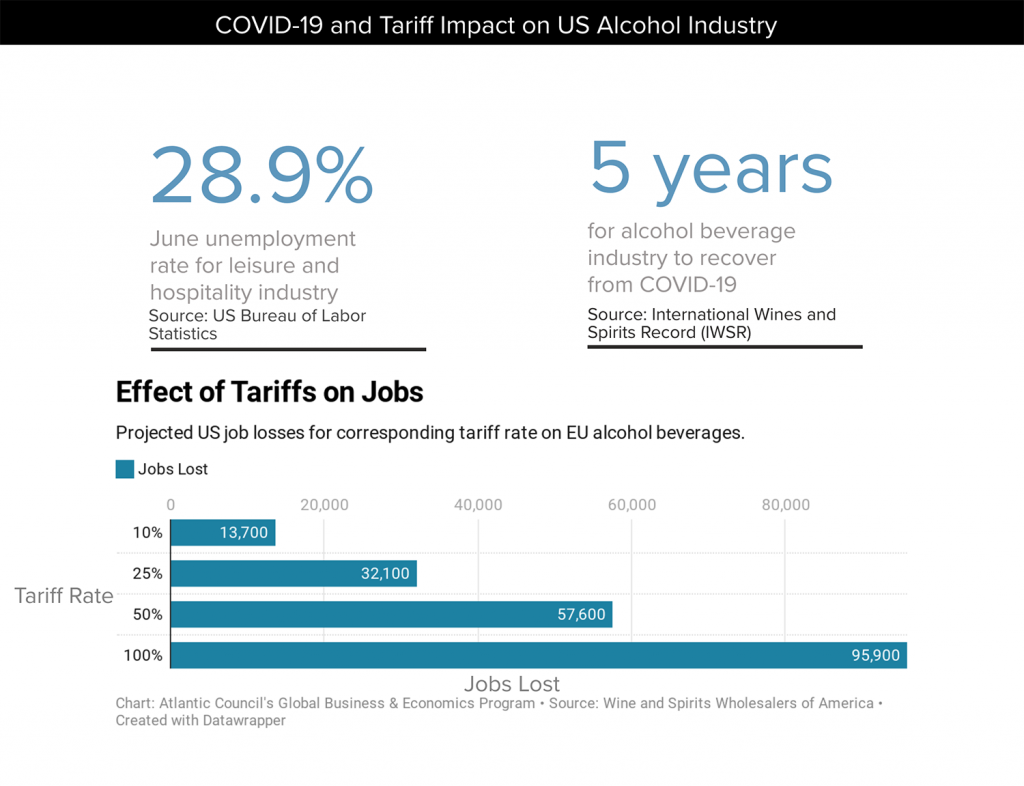

At the Atlantic Council, we have consistently argued in favor of rules-based, free trade because deadweight losses outweigh any welfare benefits as a result of protectionist measures, even if those tariffs are legal under the WTO’s framework. (In the interest of disclosure, both Airbus and Boeing have contributed to the Atlantic Council.) The above graphic uses the US hospitality sector as an example to underscore how US tariffs on European producers are hurting US companies, workers, consumers, and vice versa.

American wineries illustrate the far-reaching negative effects of the tariffs. One might contend that US wine sales benefit from higher prices on European competitors. To sell their product, however, these wineries rely on distributors, which in turn depend on domestic and foreign suppliers to survive. Increased tariffs could force many liquor distributors to close their doors and hurt US alcoholic beverage producers in the process. COVID-19 is putting immense pressure on the US hospitality sector. New tariffs would further destabilize this vulnerable industry that provides more than 10 percent of US private sector jobs.

A further increase of US tariffs within or beyond the $7.5 billion ceiling outlined by the WTO might very well trigger a European response before the WTO’s Boeing ruling that is now expected in October. Top EU Commission officials signaled during the USTR’s recent consultation period that Brussels’ patience is running out. As our fellow Marc Busch explained in an earlier piece, the EU Commission could use an older WTO case that it won against the US government to impose tariffs on up to $4 billion of American exports. Or Brussels could take the more radical step of retaliating unilaterally. The European Parliament provided the Commission with the tools to do so in reaction to the ongoing trade tit-for-tat with the United States.

Either European response would escalate transatlantic trade tensions to new heights just when both the US economy and Europe’s biggest economy Germany shrunk by roughly 10 percent in the second quarter because of the pandemic related shutdowns. Therefore, USTR should advise the president to lower or at minimum keep tariffs at the current level to de-escalate tensions with the EU ahead of the WTO decision on Boeing and save American jobs by doing so. In the same vein, the European Commission should not abandon the established WTO process by retaliating unilaterally against US tariffs authorized by the WTO. This would further undermine the WTO’s legitimacy and cause spiraling economic costs on both sides of the Atlantic.

The Airbus–Boeing dispute is an important puzzle piece of the overall EU-US transatlantic trade spat. The civil aircraft row thus lends itself to become the starting point for a transatlantic trade détente (admittedly a glass half full take), once the WTO’s appellate body finally hands down its Boeing ruling, which will determine both sides’ negotiating positions. Both companies have already taken steps to move toward better compliance with WTO guidelines by working with their host governments in Germany, France, and Spain, as well as Washington State to remove favorable interest rates and tax breaks. While the WTO is unlikely to accept these one-sided commitments at face value, the EU Commission and USTR should use this momentum to agree on a framework that governs civil aircraft financing to settle the Airbus–Boeing dispute. Such a settlement could then open the door for the world’s two largest free-market economies to re-start a constructive dialogue in 2021 on deepening transatlantic commerce by harmonizing the regulatory environment and tearing down rather than erecting new tariff walls.

Given the similar size and structure of both economies without clear lanes of comparative advantage, striking a comprehensive, TTIP like trade deal will not be easy. However, the United States needs a deal to protect against companies moving to Canada or Mexico under USMCA to take advantage of these countries’ trade agreements with the EU.

Trade could help fuel the engine to revive growth on both sides of the Atlantic after the pandemic. A mutually beneficial Airbus–Boeing settlement might just start the ignition. This should compel USTR Robert Lighthizer to make the case against increasing dispute-related tariffs to, in his office’s words, avoid causing “disproportionate economic harm to US interests, including small or medium-size businesses and consumers.”

Ole Moehr is associate director at the Atlantic Council’s Global Business and Economics Program.

Further reading:

Image: US Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer listens during a Senate Finance Committee hearing on President Donald Trump's 2020 Trade Policy Agenda on Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C., US, June 17, 2020. Anna Moneymaker/Pool via REUTERS