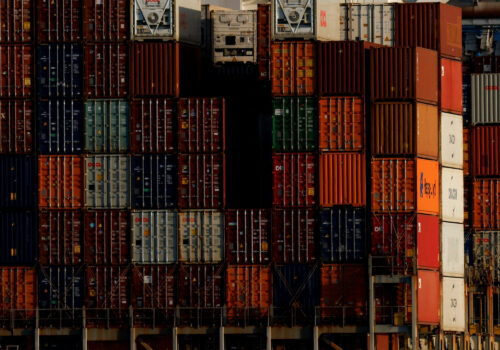

Steel yourself for escalation. The Trump administration imposed 25 percent tariffs on all steel and aluminum imports on Wednesday, a move that hits Europe, along with Canada, Mexico, and others. The European Union (EU) retaliated with targeted levies on US goods starting in April, and Canada also responded with retaliatory tariffs. What will this back-and-forth mean for the economy—and the slumping financial markets? What is the state of transatlantic relations? We turned to our experts for answers.

Click to jump to an expert analysis:

Frances Burwell: For the EU, this trade war is about more than just economics

Joseph Webster: The US auto sector loses, and China wins

Barbara Matthews: The journey to a new global trading system will not be linear—and it will be bumpy

Brussels is ready to bargain, but the US may not want to make a deal

The transatlantic trade dispute over steel and aluminum is back, almost exactly seven years after US President Donald Trump first exercised his authority under Section 232 (on March 8, 2018). Back then, the EU responded by launching a World Trade Organization (WTO) proceeding and imposing surgical levies on US exports from key Republican-leaning constituencies. In July of that year, then European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker managed to strike a deal with Trump to roll back the tariffs, promising increased purchases of US liquefied natural gas and soybeans.

This time around, Brussels was better prepared. Europe struck back immediately this morning, sticking with the “proportionate countermeasures” approach previewed by European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen a month ago. The Commission automatically reapplied suspended levies on more than four billion euros worth of US exports (steel and aluminum, bourbon, motorcycles, jeans, and orange juice) effective April 1, with plans for a second round worth over eighteen billion euros (on cosmetics, clothes, wood, soybeans, and other agricultural goods) set for April 13. Rather than punching back hard, Brussels seems to be prioritizing unity among EU member states and leaving the door open for a deal. The EU has also refrained from unleashing its new “anti-coercion instrument” and is keeping some of its powder dry. The staged approach is a signal with the Trump administration’s release of its “fair and reciprocal tariff plan” on April 2 in mind—that plan would hit a much broader cross-section of EU exports with duties. Go there and we will hit you harder, the Commission is saying.

In the lead up to this week’s tariff announcements, Brussels explored several avenues to get to a deal and avert Trump’s tariffs of 25 percent on both steel and aluminum imports, without getting any traction with the US counterparts. The back-and-forth trade threats and responses witnessed by Canada and Mexico should serve as lessons for Europe: It should firmly defend its industries, avoid signs of weakness, and leverage the continent’s economic weight and tools to respond to economic coercion. Neither Canada and Mexico’s proximity and trade integration with the United States, nor last-minute negotiation efforts by Japan, India, or Trump-friendly Australia, granted the countries exemptions.

But more fundamentally, Europe will have to confront the possibility that there may not be a deal to be had in the short term. Trump’s hyperactive tariff actions and talk of short-term economic pain for long-term gain may just betray a strategy to fundamentally shift the United States’ global economic engagement, turning its back on a seemingly broken multilateral trade system. Such a shift would pose a far greater challenge to an export-reliant and WTO-adherent EU economy than any broadside of US tariffs. Notwithstanding US market losses, early signs of economic slowdowns, and potential “transition” period ahead, Brussels must internalize the “America first” trade policy in Washington and develop a broader trade and industrial policy strategy quickly.

—Jörn Fleck is the senior director of the Atlantic Council’s Europe Center.

—Jacopo Pastorelli is a program assistant in the Atlantic Council’s Europe Center.

For the EU, this trade war is about more than just economics

The United States and the European Union are falling into a trade war, with unpredictable consequences. The tariffs and retaliatory measures related to steel and aluminum are not going to wreck either the US or EU economy. Indeed, we have experienced most of these measures before, as they were in force at the end of the first Trump administration. But this is only the opening salvo from Washington in its bid to counter what it sees as protectionist EU policies, as Trump is exploring reciprocal tariffs on all countries (which could implicate the EU auto industry) and an investigation into digital services taxes (charged by some EU member states).

Tariffs based on these policy issues—rather than on trade measures—will widen the scope of the conflict, especially if the EU responds through its anti-coercion instrument, which allows for broader retaliatory measures, including tariffs on services and intellectual property restrictions. Should the United States and EU go down this path, the damage to their economies will be far greater than that caused by steel tariffs.

But for the EU, this is not just about economics. This is about institutional recognition and credibility. Trump has made clear his disdain for the European Union, and I have heard visiting members of the European Parliament come away from meetings with Republican legislators saying they now understood that the Republicans viewed Europe as an adversary, not an ally. No meeting is yet scheduled between Trump and von der Leyen. Thus, it may be that the EU’s retaliation is also aimed at forcing the Trump administration to deal directly with the EU. If that is the case, it will be even more difficult for the EU to back down.

Whether there can be a cease-fire depends on how much economic pain the EU and the United States can withstand. Europe’s economy has been sluggish overall, and the competitiveness debate has not yet translated into real reforms and growth in productivity. In the United States, inflation remains a key concern for voters—and is likely to be worsened by tariffs—while stock market declines threaten one of Trump’s key success metrics. Both sides will need to find an off-ramp before too long.

When that moment comes, both sides will need to save face with a deal. The EU has a “deal” ready, which Maroš Šefčovič, the EU trade commissioner, reportedly proposed and that features reductions in car tariffs and pledges to buy more liquefied natural gas and defense equipment from the United States. This may not be sufficient to quiet Trump’s concerns—it may be necessary to address the issue of digital service taxes and find a way to simplify some of the implementation of EU digital laws. Many in the EU would find that a challenging pill to swallow. But if it came with an acknowledgement of the EU and its role as an economic partner, there might be a basis for a settlement.

—Frances Burwell is a distinguished fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Europe Center and a senior director at McLarty Associates.

The US auto sector loses, and China wins

The US auto sector faces tariff whiplash. While the automotive sector’s tariff rates for critical manufacturing inputs seem to be changing on a daily basis, the sector’s economic fundamentals are more rigid. Trade with Canada makes the US automotive sector more competitive. Canada accounts for about 78 percent of steel and iron and 95 percent of aluminum imports for the Detroit census district, the beating heart of the US auto industry. Steel and aluminum are critical cost drivers for autos; lightweight aluminum is used extensively in electric vehicles. With few near-term alternatives to Canadian steel and aluminum providers, US automakers will be forced to accept higher costs from domestic producers of these materials. Accordingly, US automakers will be forced to pass on higher input costs to consumers, cut production, and eliminate jobs. Investment plans will be stalled due to uncertainty. Crucially, the US auto sector will become less competitive relative to international competitors—especially Chinese companies.

Chinese automakers will be the primary beneficiaries of the tariffs. Not only will US automakers’ competitiveness suffer from higher input costs, but other trading partners—Europe, Mexico, and especially Canada—might begin to consider Chinese-made electric vehicles and connected vehicles as more appealing on commercial and diplomatic grounds.

—Joseph Webster is a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Global Energy Center and Indo-Pacific Security Initiative; he also edits the independent China-Russia Report.

The journey to a new global trading system will not be linear—and it will be bumpy

Steel and aluminum have been in the crosshairs of tariff policy for over a decade, so today’s tariff actions are not exactly extraordinary. They also create no surprises; today’s tariff action was highly publicized well in advance. The reaction from US trading partners is far from surprising as well: retaliatory tariffs on key US exports. Today’s moves may not be surprising, but they are strategically significant as major advanced economies continue to redefine the terms of their trading relationships. The United States is telling trading partners that the traditional mechanisms for managing trade policy no longer function for a US economy that looks increasingly inward when defining trade policy priorities.

Structural economic shifts are inevitable as a consequence. The journey away from Bretton Woods will not be linear, and it is certain to be bumpy.

For example, Ontario’s climb-down regarding electricity trade with the United States and the White House’s retaliation threat on March 11 illustrate how swiftly tariff policy can shift toward more benign outcomes. Policymakers in North America pulled back from the brink of a debilitating retaliation dynamic that would have damaged both economies. Future pullbacks may also be possible amid complex geopolitical negotiations between the United States and its trading partners.

Like the Bretton Woods structure, the new terms of trade will articulate a new balance of geo-economic power. US initiatives to strike bilateral bargains that protect strategic priorities (e.g., national security, increased domestic manufacturing, access to critical minerals, the export of civilian nuclear technologies) will operate in tandem with ongoing EU and UK initiatives to increase bilateral trade and economic partnerships that prioritize climate-related goals (e.g., carbon emissions reduction, expanded clean energy and hydrogen, the achievement of sustainable development goals). Unlike the Bretton Woods structure, the process for changing the terms of trade clearly will be bilateral rather than multilateral; it will likely take months if not years before a new equilibrium has been reached.

As markets and strategists evaluate escalating trade policy tensions, they need to prepare for a protracted period of policy volatility that assess the impact of both tariff increases and any negotiated delays or tariff decreases. Additional disruption should be expected. At least two significant inflection points remain on the foreseeable horizon. First, the United States on April 2 plans to revive a reciprocal foundation for cross-border trade that effectively neuters the multilateral trade policy structure that the United States championed for over seventy-five years. Second, the silence regarding China’s role in the global trading system is deafening and telling.

As policymakers from Washington to Brussels to Ottawa to Canberra to Tokyo redefine their mutual terms of trade, how and when they break their silence regarding China will be at least as strategically significant as the current reactions and retaliations regarding US trade policy.

—Barbara C. Matthews is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council. She is also CEO and founder of BCMstrategy, Inc and a former US Treasury attaché to the European Union.

Further reading

Wed, Mar 12, 2025

Note to Trump: McKinley’s legacy is about more than tariffs and territory

New Atlanticist By Daniel Fried

President William McKinley’s foreign policy was more complex than his reputation for high tariffs and imperial acquisitions would suggest.

Tue, Mar 4, 2025

A Wall Street wake-up call on Trump’s tariffs

Fast Thinking By

As markets fall in response to the US decision to increase the cost of importing goods from Canada, Mexico, and China, how is the US president thinking about tariffs?

Mon, Mar 3, 2025

The art of the transatlantic deal

Report By Frances Burwell

The transatlantic relationship is shifting with US president Donald Trump's return to the White House. Nevertheless, discreet deals across the US-EU trade, energy, and defense sectors are possible.

Image: Annealing steel slabs lie on a rolling mill in the Ilsenburger Grobblech GmbH rolling mill in Ilsenburg. Ilsenburger Grobblech GmbH currently employs 700 people. The plant produces high-quality quarto plates. A modern training and communication center will be built here by 2026.