The death of Colin Powell was a rare moment that galvanized Washington in celebration of a figure who (almost) transcended politics: a man of the 1960s but of the Greatest Generation in spirit. Americans outside the Beltway became acquainted with Powell when he served as the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff during the Gulf War. Along with the bombastic and more media-friendly General H. Norman Schwarzkopf, who commanded coalition forces in the war, Powell embodied an entire generation’s military redemption in the near-total victory of US and allied forces against Saddam Hussein’s Iraq.

In the end, there was an irony in the symmetry of his career. His professionally formative years had come at the end of one pivotal American moment; he had lived through the dark days of Vietnam and afterward helped lead long enough to watch a similar misadventure repeated in Iraq.

Famously, he had opposed the Iraq invasion. As members of the US military and policy community vacillated over foreign policy and the use of force following the Vietnam War, Powell came to support, then refine, the military doctrine of former US Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger: A nation should exhaust all its non-military means before adopting more forceful measures. Military interventions should attract international support, have clearly defined objectives, and feature an exit plan. If they don’t—and Vietnam didn’t—US leaders should consider other options.

The Gulf War seemed to verify the wisdom of the Powell Doctrine. It was a short, sharp conflict sparked by Hussein, who committed the clearest possible violation of international norms and standards in the emerging post-Cold War world by occupying and annexing a neighbor—Kuwait. Hussein made no attempt to disguise his encroachment, and when the international community told him to leave, he refused. Hussein aided the American casus belli; his regime was among the most brutal in the world, and he had developed his military according to Soviet methods that US forces were trained to fight. No more guerilla war in the jungle: This was straight shock and awe.

The outcome was so uneven, and the casualty count so unbalanced, that US technological dominance seemed to represent a revolution in military affairs—which of course helped validate the Powell Doctrine as well. Synthesizing the coalition’s high-tech airpower, computers, satellites, communications, and command-and-control against a degraded, Soviet-style enemy without nuclear weapons resulted in victory in a matter of hours. The United States’ Vietnam hangover was gone, blown away by technological ingenuity applied together with solid strategy. It was a triumph, and Powell was the highest-ranking military officer in the US armed forces at the time.

There were some holes in this narrative, of course. For one, the Powell Doctrine was not a complete answer to the wars of the 1990s. It was not even a complete answer to the Gulf War, which quickly devolved into a brutal intrastate, sectarian conflict that US soldiers stood by and watched. Iraqi Shia, perhaps emboldened by then US President George H. W. Bush’s call to oppose Hussein’s tyranny, indeed rose up and were slaughtered by Hussein’s forces. It was a grotesque end to a chapter of international cooperation that, along with the collapse of the Soviet Union, seemed to herald a brighter day for humanity.

Hussein’s actions were then repeated in different places around the developing world. The ethnic violence in Yugoslavia, Rwanda, Sudan, and elsewhere contributed to a building consensus that the policy modesty of the 1990s was no longer good enough—that the international community should do more to stop genocide and protect basic human rights within states. The United Nations’ (UN) “Responsibility to Protect” concept was pioneered by then UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan from his experience in the genocides of the 1990s. It was in part the anti-Powell Doctrine, with its focus on messier intrastate wars likely precluding a clear exit strategy.

There was also a smaller consensus (mostly among Americans) that the United States should use the unipolar moment to act more vigorously to advance not only its own interests, but also those of the world; after all, the two were synonymous. By the time of the George W. Bush administration—and certainly after the terrorist attacks of 9/11—the Powell Doctrine seemed almost quaint, a device of an older generation of US leaders who were too haunted by Vietnam to aim at anything more than the most limited possible objectives. If the United States, at its apogee, would not do something about the worst states on the planet, then what was the point of all that power?

For Powell, the Iraq invasion smacked of everything he had seen in Vietnam, leading him to refine his doctrine into the Pottery Barn principle of “you break it, you own it.” He saw an immensely complicated and dangerous task ahead in patching together a multi-sectarian Arab nation—one for which the United States was manifestly unsuited. He assisted with it nonetheless: Few could forget his 2003 appearance the UN, where he pushed faulty intelligence on Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction program. By the time the insurgency really hit, in 2005, Powell had left, tired of jousting with then Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld and then Vice President Dick Cheney.

It was the Iraq war, more than anything else, that shaped foreign policy in the modern Republican Party, which is where Powell made his political home for years before shifting away. The second irony of Powell’s career and his doctrine is that it would have been far more at home in the next Republican administration than in his own. In the end, Powell won the debate over the use of force. It was telling that the two most successful GOP candidates in 2016 explicitly ran against regime change, and the winner and eventual president ran explicitly against the Iraq war. Today, it is difficult to see a majority of GOP voters going for something other than the basic maxims of clear exit strategies, realism about the limits of US power, force as last resort—and, for God’s sake, no more regime change.

Dr. Andrew Peek is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Middle East Programs. He was previously the senior director for European and Russian affairs at the National Security Council and the deputy assistant secretary for Iran and Iraq at the US Department of State’s Bureau of Near Eastern Affairs.

Further reading

Mon, Oct 18, 2021

The Powell Doctrine’s wisdom must live on

New Atlanticist By Christopher Preble

Colin Powell’s criteria governing the use of force abroad aimed to ensure that war is always a last resort. US leaders shouldn't forget that as they honor his legacy.

Fri, Oct 22, 2021

Colin Powell’s glorious American journey

New Atlanticist By Harlan Ullman

As a gentleman, Powell treated all people with great respect—no matter their rank or status.

Fri, Oct 22, 2021

The US needs to reinvent its alliances. Today’s threats demand it.

New Atlanticist By

When it comes to working with allies, business-as-usual won’t cut it anymore for the United States—especially in the face of growing Chinese and Russian competition.

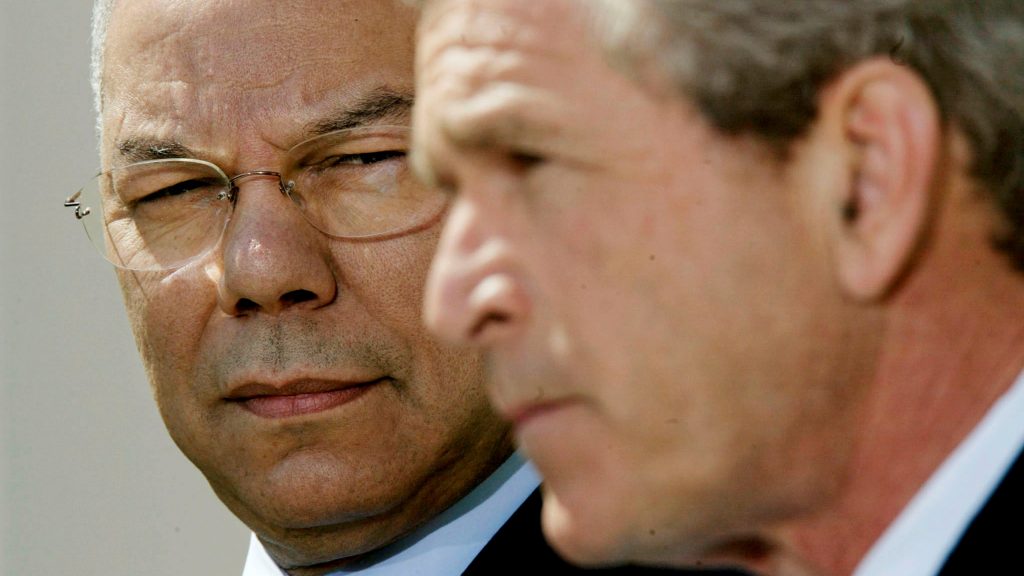

Image: Then Secretary of State Colin Powell looks on as President George W. Bush speaks on April 4, 2002. Photo by Kevin Lamarque KL/MMR/File Photo/REUTERS