On August 19, the Trump administration issued an executive order (EO 13936) suspending and terminating three bilateral agreements that establish a range of preferential arrangements for Hong Kong. The move was not a surprise. It reflects ongoing and escalating efforts by the United States to penalize the Republic of China and Hong Kong for rollbacks of civil liberties over the last year.

Most of the media coverage concerning the executive order focused on the elimination of extradition arrangements, but few noticed the action included suspension of reciprocal tax exemptions on income derived from the international operation of ships.

Suspending the tax treaty is a technical but significant move. It means that corporations subject to US tax jurisdiction earning income from the international operation of ships through the port of Hong Kong will now incur tax liabilities in the United States. 12 CFR. §1,883-1 applies to all passenger and cargo traffic that begins and ends in the United States and involves unloading or disembarking outside the United States. It covers both sea and air vessels.

Until the executive order was issued, such cross-border traffic was exempt from US tax liability. The tax exemption created incentives for bilateral trade flows between the United States and Hong Kong. Eliminating the exemption in theory places pressure on export earnings from neighboring mainland China exporters that have been shipping goods to the United States through Hong Kong in order to benefit from the effective lower tax rate.

But will the move be an effective tool to incentivize a shift in Chinese economic or civil liberties policy?

Data point to a marginal impact

A quick look at high level trade flow data between Hong Kong and the United States suggests that reintroducing a tax on revenue may not generate the preferred incentives even when it generates political attention.

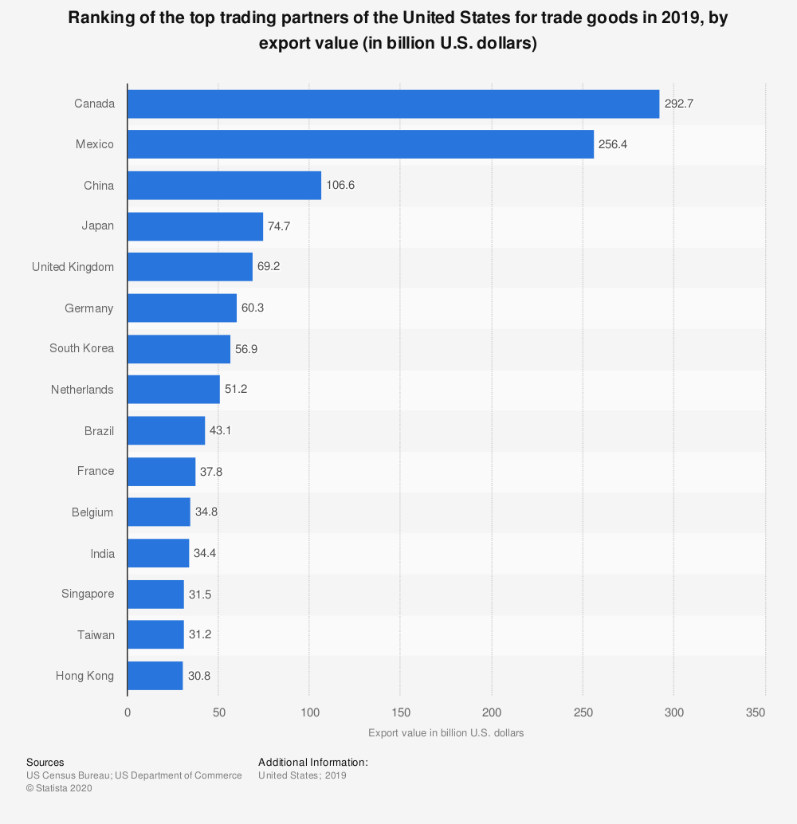

The bilateral trading relationship between the United States and Hong Kong is just not that big. While Hong Kong did rank as one of the top ten US trading partners in 2019, it was in last place. As the data on the right indicates, trade flowing between Hong Kong and the United States was just over 10 percent of the value of the bilateral Chinese/US relationship. If Chinese exporters were using Hong Kong as a back door to qualify for the bilateral tax treaty, they were not using that route at scale.

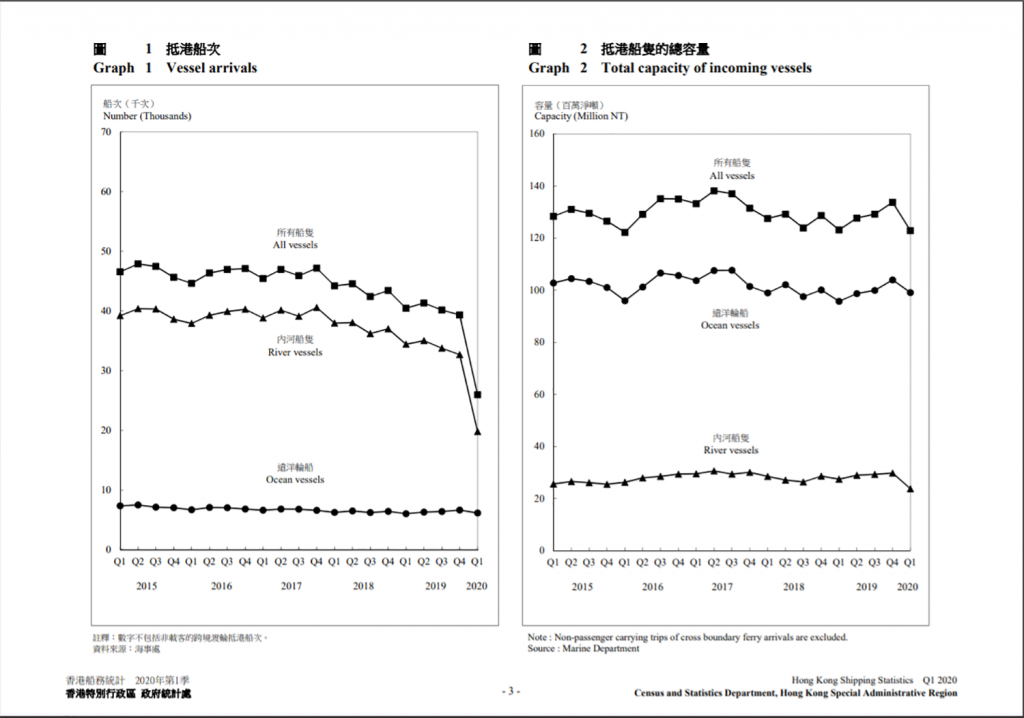

Even if the trade relationship were not significant in the aggregate, the question then becomes whether the trading relationship during the pandemic acquired additional importance for which elimination of the tax exemption would be significant. The data here is mixed as well. Traffic through the port of Hong Kong was diving in the first quarter of 2020 (the most recent period for which data is available), just as the pandemic was gaining momentum in China. Data from the port of Hong Kong show a steep drop-off both in the number of vessel arrivals and the total capacity of incoming vessels between the fourth quarter of 2019 and the first quarter of 2020:

The data also indicate that geopolitical and policy tensions regarding how Beijing chooses to govern Hong Kong from afar did not materially or adversely impact inbound trade through the port of Hong Kong since the current round of protests and restrictions on civil liberties originated in the summer of 2019.

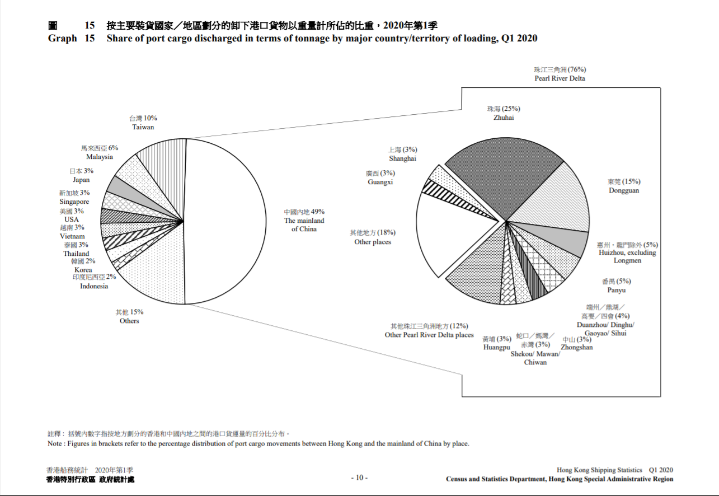

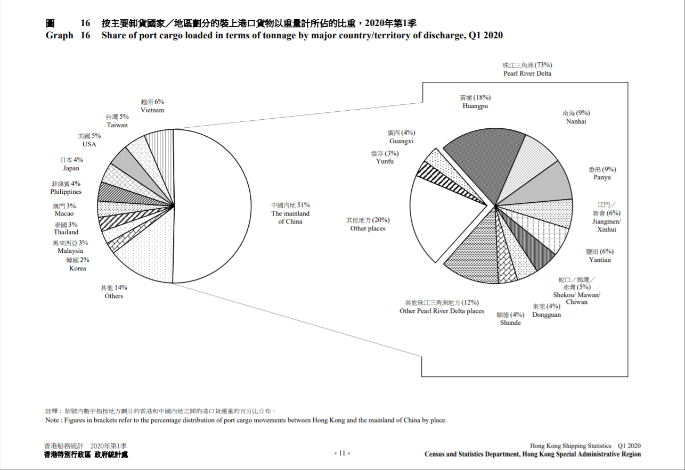

Most troublesome for the Trump administration, the United States is not a significant a trading partner to Hong Kong. The United States accounts for only 3 percent of inbound port cargo and only 5 percent of outbound port cargo.

Hong Kong’s single largest trading partner, unsurprisingly, is the Republic of China. This suggests strongly that economic sanctions may have limited utility in shifting Beijing’s policy priorities regarding civil liberties and national security in Hong Kong.

Economic sanctions as a strategic signal

Economic sanctions have a famously uneven success rate. In general, economic sanctions have had limited effect when the objectionable policy is not economic in nature. Even the most comprehensive economic sanctions against countries like Iran and North Korea have done little to incentivize foreign sovereigns to shift policy priorities.

In the Hong Kong context, the Trump administration’s economic sanctions policy has not been limited to withdrawing the tax exemption. It also, and more significantly, is requiring that products manufactured in Hong Kong now be labeled “made in China.” The Hong Kong government is preparing a complaint to the World Trade Organization (WTO) regarding this labeling policy.

In other words, the tax policy needs to be evaluated within a broader context. The underlying policy disagreement regarding Hong Kong technically has nothing to do with tax and trade. The core of the dispute centers on what it means to be sovereign. It centers on self-determination and the values of democratic government including, but not limited to, free speech, freedom of assembly, and representative government in which citizens determine the rules by which they will be governed.

Hong Kong presents a most difficult policy challenge for western liberal democracies. The people of Hong Kong have had no voice regarding the new national security law imposed on them this summer from Beijing. But few expected to see representative government regarding Hong Kong from China’s capital.

The ninety-nine-year British rule operated under a temporary lease which expired in 1997. In China at the time, the “handover” back to Beijing was viewed with as much joy and validation as the reunification of Germany after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Hong Kong was permitted to keep its separate seat at the WTO. Even Beijing’s promises about preserving the unique political culture in Hong Kong (“one country, two systems”) were not designed or viewed at the time as a permanent (much less enforceable) promise to preserve western liberal democratic traditions in the enclave.

US and European policymakers face the current situation in Hong Kong with limited tools. Increased reliance by advanced economies on national security justifications for investment reviews and supply chain diversification effectively muffle their ability to object when other sovereigns use national security justifications in objectionable ways. Amid a pandemic that has already erased an unprecedented amount of economic growth globally during 2020, and facing an uncertain path forward due to the COVID-19 pathogen, policymakers globally will be understandably hesitant to provoke a trade war with China no matter how just the cause.

Separate from the pandemic and the geopolitical situation with China, the global trading system is experiencing a significant shift towards services and an increase in more distributed ways of executing cross-border commerce…often through cloud-based platforms. As I wrote for the Bretton Woods Committee last year, the most important trade policy issues today “address standards (labor, environmental, phytosanitary, financial stability) and intangibles (intellectual property, data transfers, digital assets and processes) that do not fit neatly into a trade paradigm crafted for a world where trade mostly involved physical goods. The growing reliance on 3-D printing in the manufacturing process and trade in services will decrease further the number of physical items crossing borders.” In this context, a tax on people and goods that physically cross borders create additional hurdles for the potential transfer of sensitive technology and information that occur whenever people have in-person conversations.

Eliminating the favorable tax treatment and requiring “made in China” labels at least provide a visible and concrete mechanism to articulate objections regarding Chinese policy without exerting significant economic pain on the people of Hong Kong, China, or the United States. These are important policies whose signaling value far outweighs the relatively small economic pain they are likely to impose.

Barbara C. Matthews is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council. She is also CEO of BCMStrategy, Inc., a technology company using patented processes to measure public policy risks. When in government she served as the first US Treasury attaché to the European Union, with the Senate-confirmed diplomatic rank of minister-counselor.

Further reading:

Image: People wearing face masks following the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak look on at the Tsim Sha Tsui ferry pier in Hong Kong, China July 14, 2020. REUTERS/Yik Lam/File Photo