China is making subtle but important changes to its security presence overseas. Adopted by China’s State Council in late June, the Regulations of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) on Consulate Protection and Assistance (the Regulations) took effect on September 1. In the twenty-seven articles making up the Regulations, Beijing has outlined the roles and responsibilities of its embassies and consulates on overseas security affairs. The new rules are part of Beijing’s broader security narrative aimed at increasing the PRC’s security footprint abroad in the name of protecting Chinese nationals overseas. By expanding this footprint, however, the PRC could also grow its capacity to carry out transnational repression.

For decades, Beijing paid little attention to addressing security issues faced by PRC nationals overseas. Even before the Belt and Road Initiative took off, the large population of Chinese workers sent abroad to fulfill infrastructure contracts periodically faced security challenges from local conditions. But many of these challenges came from Chinese managers, who operate in nearly unchecked environments. Chinese workers are often in “conditions indicative of forced labor, such as withholding of passports and other restrictions on movement, nonpayment of wages, [and] physical or sexual abuse,” according the US Department of State’s 2012 Trafficking in Persons Report.

More recently, Beijing has expanded its definition of its national interest when it comes to security issues. China’s 2015 National Security Law and the 2016 National Defense Transportation Law—and the new Regulations, too—advance a whole-of-society approach to overseas securitization. As part of this approach, Beijing is pressing state and private enterprises to provide support for military actions in the protection of the PRC’s overseas interests. This support could include assisting in the repression of Chinese dissidents abroad, among other measures.

The Regulations are worth looking at in more detail. Host countries need to be aware that Beijing could use the rules to further its repression of Chinese dissidents and expand its security and intelligence apparatuses via its embassies and consulates. Preventing this will require host countries to draw red lines with Beijing regarding what actions the PRC can and cannot take under the new Regulations.

Transnational repression

Two parts of the Regulations raise new questions for countries that host large numbers of PRC nationals. Article 7 states that PRC embassies can act unilaterally under “special circumstances,” granted that there is “permission from the host country.” Host countries should clarify what constitutes a permission under the Regulations, especially if any existing law enforcement cooperation agreements with the PRC uses vague language that may be interpreted as permission to legitimize transnational repression. The wording of Article 7 is especially concerning due to the broad scope of the term “Chinese nationals,” many of whom hold dual citizenship.

In addition, Article 3 of the Regulations states that consulates are responsible when the “rights of [Chinese nationals] are violated,” or simply, “if help is needed.” The full scope of responsibilities that fall under this broad definition is not elaborated, but the Regulations give examples such as “disputes with [host country] intermediaries, tour operators, and transport agencies.” This emerging rationale will likely widen the scope of “legitimate” unilateral actions on the part of Chinese actors, in addition to existing unilateral extraterritorial “law enforcement practices” under Chinese covert operations, such as Fox Hunt and Sky Net. These actions could include kidnapping programs justified as part of Beijing’s “anti-corruption” campaign, targeting Chinese nationals overseas who have committed “economic crime” in China. However, the case of Swedish citizen Gui Minhai’s case is instructive. After he was abducted from Thailand in 2015, Gui was initially charged by China with “illegal business operations,” but he was tried in 2020 for “illegally providing intelligence overseas.”

China might target a Chinese nationals abroad under almost any pretext, but the Regulations could provide formal grounds for PRC consulates to intervene in the overseas private affairs of Chinese nationals whether they welcome government support or not. Indeed, Articles 11 and 13 state that PRC consulates may act if they have been notified by family members of overseas Chinese nationals who remained in the PRC.

Expanding overseas security

As part of Beijing’s securitization trend overseas, the new Regulations push forward a whole-of-society approach. As Beijing’s expectation of overseas security management grows, the call for PRC embassies around the world to facilitate Beijing’s overseas security management will likely increase, too. Particularly, as Article 18 of the new Regulations states, more work on assessments and prevention is needed not only in the event of an emergency, but for “routine, daily security needs” as well. Beijing will likely devote more resources and personnel to produce on-the-ground risk assessments, as well as crafting new prevention and response strategies. Once Beijing has built confidence over the local context, it will likely then be able to better exploit gray areas to introduce new types of security presence while minimizing opposition.

PRC embassies will also be able to leverage resources from local-level provincial governments to facilitate security work. In cases where local-level provincial governments have already established subnational influence in targeted countries and communities, the integration of efforts from various Chinese actors will boost Beijing’s decision-making in security affairs.

The emphasis on gaining better access to information about foreign affairs was previously discussed in a 2018 Guide on the Safety Management of Overseas Chinese-Funded Companies, Institutions, and Personnel, which was published by the PRC Ministry of Commerce. The guide itself instructed overseas Chinese companies to take their security needs seriously, calling intelligence work the “foundation” to any security engagement. This guide also suggested that a “Belt and Road National Security Intelligence System” is on its way to decentralize and synchronize information sharing between informal and state-level Chinese actors.

It’s therefore no surprise that aside from state-level actors, other non-state entities, including overseas private Chinese companies, are also being drawn in. The new Regulations also introduce a reward scheme encouraging “volunteers” to support the consulate in their security responsibilities. In 2016, Beijing reported that twenty of its embassies have started to experiment with this “volunteer” system. One of the embassies, in Cyprus, issued a press release in 2018 on the roles of “volunteers.” Among several tasks, volunteers were asked to provide local security risk assessment and facilitate risk prevention activities, develop communication channels between the local government and the embassy, and provide on-site assistance to embassy staff in cases of “natural disasters” and “emergencies and accidents involving a Chinese national.”

In the past six months, other PRC embassies around the world have started the recruitment process for this volunteer program. One March 2023 press release from the PRC embassy in Prague specifically targeted volunteers who are “overseas Chinese nationals, overseas Chinese students, Chinese employees of Chinese companies,” and most problematically, “ethnic Chinese who have migrated to the Czech Republic” and who may have local citizenship.

Drawing clear boundaries

As Beijing continues to lay the foundations for its overseas security management, it is necessary to draw clear boundaries of accepted activities under these new Chinese security laws and regulations. The sovereign right of host countries and their security responsibilities to foreigners should take precedence over those of a foreign government. In response to the Regulations, host countries should explore building an independent communication channel with non-state-affiliated Chinese nationals living within its borders to assess the actual security risks and concerns on the ground.

In addition, host countries of PRC embassies should reach agreement with the PRC to determine what constitutes “special circumstances,” and what exact unilateral activities are permitted for Chinese actors to conduct under existing law enforcement cooperation agreements. It is also essential for host countries to clarify with the Chinese side the local laws, regulations, and restrictions that apply to any non-state Chinese actors who are being encouraged to implement security-related activities.

While Beijing seems intent on bolstering its overseas security and intelligence activities through its embassies and consulates, it is up to each host country to prevent the PRC from using the initiatives introduced in the new Regulations to grow its capacity for transnational repression and to exploit gray areas to build a larger security presence.

Niva Yau is a nonresident fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Global China Hub. Her research work focuses on China’s new overseas security management infrastructure.

Further reading

Mon, Sep 18, 2023

Global China Newsletter: Xi stiffs the G20, turns to the Global South

Global China By Dexter Tiff Roberts

The September 2023 edition of the Global China newsletter.

Wed, Aug 16, 2023

The United States and its allies must be ready to deter a two-front war and nuclear attacks in East Asia

Report By Markus Garlauskas

This report highlights two emerging and interrelated deterrence challenges in East Asia with grave risks to US national security: 1) Horizontal escalation of a conflict with China or North Korea into simultaneous conflict; 2) Vertical escalation to a limited nuclear attack by either or both adversaries to avoid conceding.

Wed, Jun 21, 2023

How Beijing’s newest global initiatives seek to remake the world order

Issue Brief By Michael Schuman, Jonathan Fulton, Tuvia Gering

Recommendations on how US policymakers and European and Indo-Pacific partners can better understand China’s latest development and security initiatives to meet the rising competition.

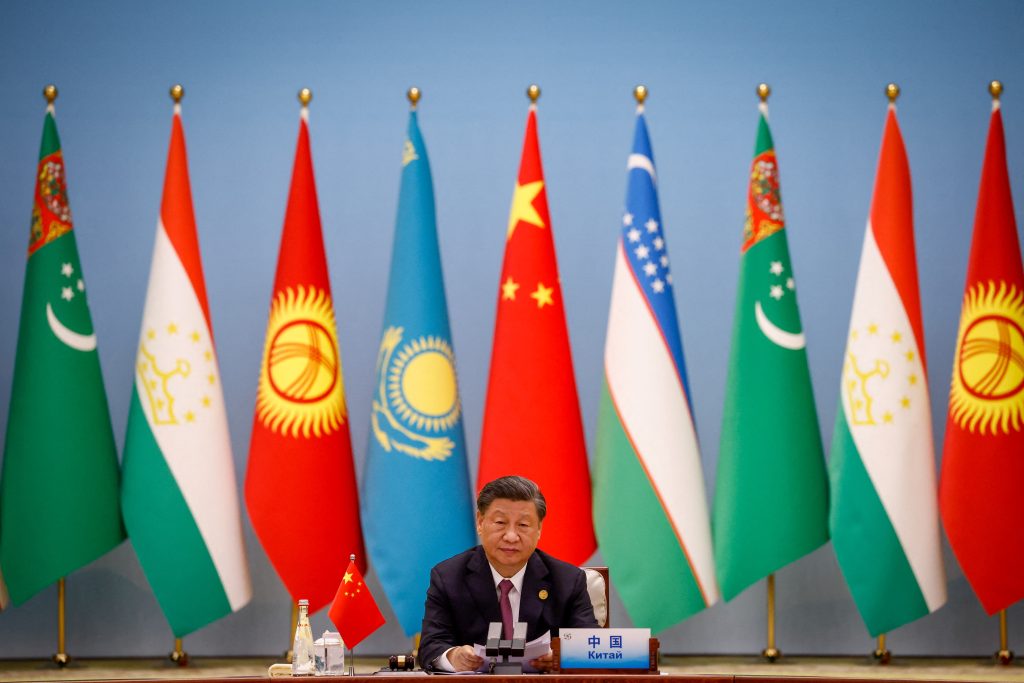

Image: Chinese President Xi Jinping speaks at the round table during the China-Central Asia Summit in Xi'an, Shaanxi province, China, May 19, 2023. MARK CRISTINO/Pool via REUTERS