Like many countries, Pakistan was likely hoping for a reset with the new Biden administration, one that could refocus relations on the country’s most pressing issues. In Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan’s congratulatory message to US President Joe Biden after his inauguration, Khan said he looked forward to working together to build “a stronger [Pakistan]-US partnership through trade and economic engagement, countering climate change, improving public health, combating corruption, and promoting peace in [the] region and beyond.”

But if Khan had any hope of resetting the bilateral relationship this year, it has been seriously dampened by the developments of the past couple weeks: The Supreme Court of Pakistan effectively ordered the release of four men who in 2002 were convicted and sentenced to death or life in prison by a Pakistani anti-terrorism court for the kidnapping and murder of journalist Daniel Pearl of The Wall Street Journal. While the Supreme Court upheld the kidnapping convictions, it acquitted Ahmed Omar Saeed Sheikh, the British national who masterminded the plot, and his co-defendants of the murder convictions. Their sentences were thus reduced to time served.

Following international condemnation, including a statement from White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki that the White House was “outraged” by the high court’s decision, the Pakistani government has sought to review the judgment. But the review is unlikely to yield a different result, which means that all four men could be free soon.

Terrorism cases can be challenging to prosecute under the best circumstances. This is especially true in Pakistan, where witness intimidation, forensic evidence (or lack thereof), and political interference can all have an effect on the verdict. But the legal terrain need not be limited to Pakistan. In this case, the United States also indicted Sheikh in 2002. And according to Secretary of State Antony Blinken, the US is “prepared to prosecute Sheikh” in the country “for his horrific crimes against an American citizen.” Acting US Attorney General Monty Wilkinson similarly stated that “the United States stands ready to take custody of Sheikh to stand trial here on the pending charges against him.”

If Khan really wants to prevent a return to the antagonism between Pakistan and the United States that characterized the Obama era, his best choice is clear: The Pakistani government should extradite Sheikh to the United States. Such a move is not without precedent. Pakistan inherited a US extradition agreement from the British and has previously helped to capture and hand over other wanted terrorists, including World Trade Center bomber Ramzi Yousef and Mir Aimal Kansi, who shot and killed two Central Intelligence Agency employees outside the agency’s headquarters in 1993.

For political and legal reasons, extraditing Sheikh may be difficult for the Pakistani government. Turning Sheikh over to the United States after Pakistan’s courts have delivered a verdict risks undermining public faith in the judiciary, and handing him to the US would also give Khan’s political opponents the ammunition they need to portray him as weak.

Given the heinous nature of Sheikh’s crimes, however, the Biden administration is unlikely to have any sympathy if the Pakistani government fails to either reverse Sheikh’s acquittal or turn him over to the United States for trial. Biden has in the past shown a willingness to treat Pakistan as a substantive ally. He was supportive, for instance, of the Kerry-Lugar-Berman bill that delivered $1.5 billion in US non-military aid to Pakistan. But the Sheikh judgment yet again brings to the forefront of the US-Pakistan relationship Pakistan’s perceived failings on counterterrorism issues. If the Biden administration comes to doubt Pakistan’s ability or willingness to take domestic national-security issues seriously, relations will remain what they have long been: tense, transactional, and characterized by a lack of trust.

While the Pakistani government asserts that there is a clear separation of powers between the executive and judicial branches, the judiciary’s decision to placate extremist elements makes it less likely that the United States will see Pakistan as the kind of like-minded democracy that it’s hoping to partner with in the region. If Khan wants to achieve his goals with the United States, he must surrender Sheikh or watch his country endure another four years as a footnote in US counterterrorism policies.

Safiya Ghori-Ahmad is the South Asia director at McLarty Associates, a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center, and a former South Asia advisor at the US State Department and Senate Foreign Relations Committee.

Further reading

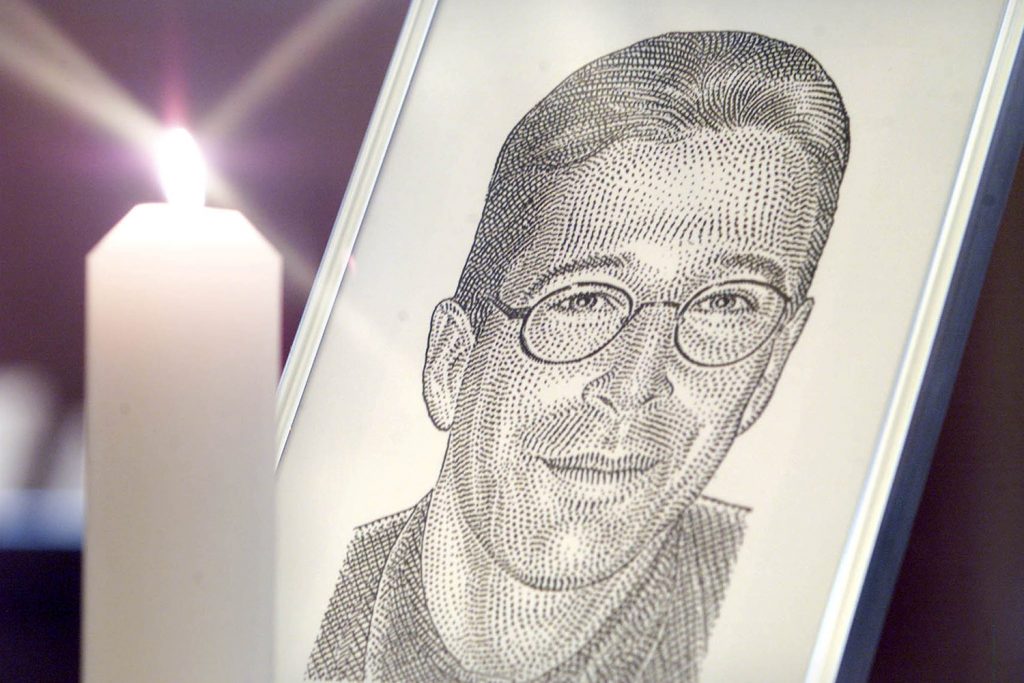

Image: A portrait of the Wall Street Journal's reporter Daniel Pearl stands with a candle at the altar at Fleet Street's journalists chapel St Brides Church prior to a memorial service in London March 5, 2002. REUTERS/Ian Waldie, IW/NMB