As Russia continues its assault on Ukraine, the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab) is keeping a close eye on Russia’s movements across the military, cyber, and information domains. With more than seven years of experience monitoring the situation in Ukraine—as well as Russia’s use of propaganda and disinformation to undermine the United States, NATO, and the European Union—the DFRLab’s global team presents the latest installment of the Russian War Report.

Security

DFRLab confirms increased Russian air force activity as Kremlin strives to achieve air dominance

Russian army continues to pressure Ukraine in Bakhmut

Tracking narratives

Volunteer Russian unit fighting for Ukraine reportedly infiltrates Bryansk

Kremlin-linked Telegram networks coordinated to spread disinformation around the world

Media policy

Report examines Russia’s decentralized approach to internet censorship

DFRLab confirms increased Russian air force activity as Kremlin strives to achieve air dominance

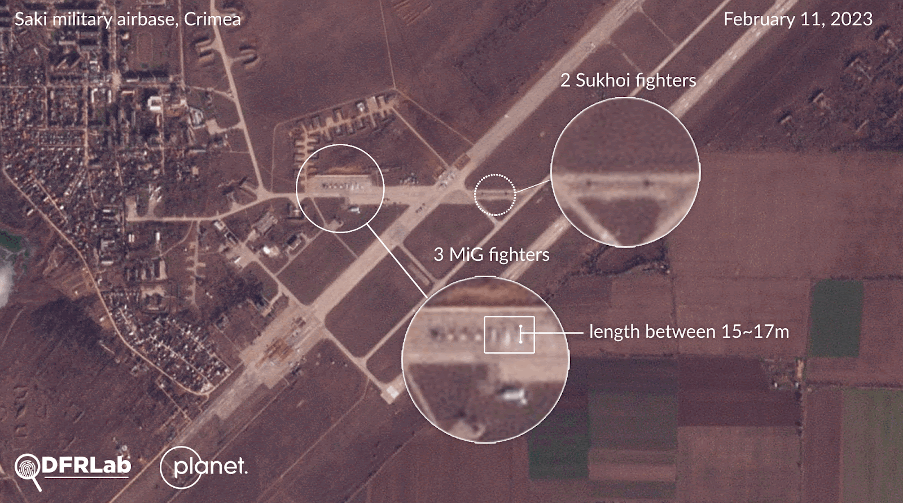

The DFRLab confirmed that the Russian General Staff has intensified its air power in recent weeks across airfields in Crimea and Rostov Oblast. Satellite imagery collected by the DFRLab throughout February indicates that Russian air forces have increased their aerial activity at the Saki military airbase in western Crimea. Several MiG and Sukhoi class fighter aircraft have been identified in standby positions or on the runway.

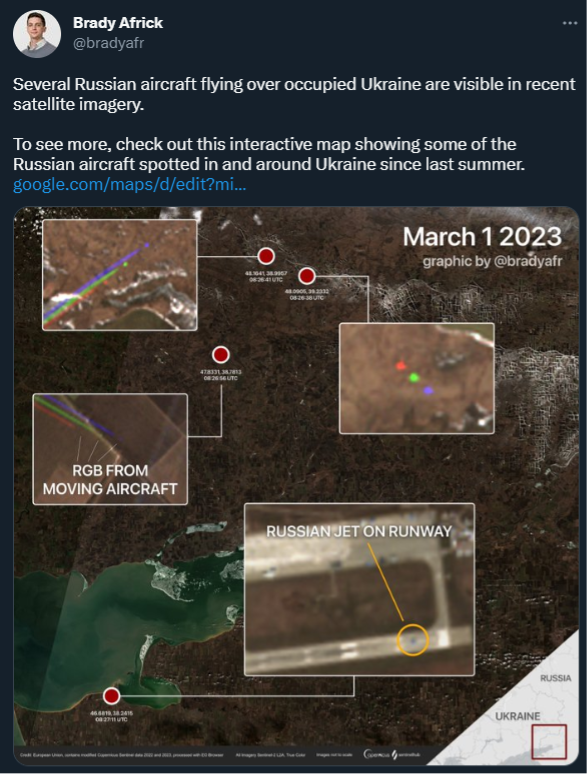

The DFRLab’s findings are consistent with those published by open-source researcher Brady Africk, who identified seven different instances of aircraft located in the south of Ukraine on Sentinel-2 satellite imagery. The European Space Agency’s satellite imagery also serves as open-source evidence of the aircraft’s direction, located in the different color bands of Sentinel-2.

In addition, explosions reported at the Yeysk military air base in Krasnodar Krai further suggest the Russian army has been increasingly intensifying its air maneuvers. Geolocated footage of a Sukhoi-25 fighter aircraft near Luhansk indicated that further maneuvers can be expected from Russia’s western air base of Millerovo. The DFRLab also assessed that air activity possibly occurred during the last week of February at a seemingly deserted airfield south of Luhansk. Satellite imagery shows that although the meteorological conditions in January and February were mostly snowy, the main runway and several pads dedicated to aircrafts and helicopters were consistently clear of snow. Satellite imagery has not yet detected aircraft at the site, however, so it is unclear what class of aircraft is currently deployed in this airfield. Nevertheless, the operation of MiG and Sukhoi class fighters could be responsible for the melting snow on the pads.

Google Earth imagery from 2021 showed the airbase in dire condition, which could support the claim of its low military activity.

As battles intensify to seize Bakhmut, the southern air base near Luhansk could serve as a strategic advantage for the Russian armed forces as it requires less fuel and maneuvers.

Meanwhile, Ukrainian forces continue to target strategic Russian installations on the southern front. On March 1, the Russian defense ministry claimed it had downed more than ten Ukrainian unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) in an attack against occupied Crimea. This comes as unverified reports suggested a Ukrainian UJ-22 drone was also downed on February 28 between Moscow and Ryazan. Ukrainian presidential advisor Mykhailo Podolyak denied the accusation and said Ukraine is not launching attacks on Russian soil; he claimed the increased aerial strikes on infrastructure were the result of “internal attacks.” Open-source evidence suggests explosions near Yalta and Bakhchysarai, Crimea, could have resulted from other projectiles, not exclusively drone strikes.

—Valentin Châtelet, Research Associate, Security, Brussels, Belgium

Russian army continues to pressure Ukraine in Bakhmut

Russian forces continue their efforts to encircle and capture the eastern Ukrainian city of Bakhmut. Interviewed by Reuters on February 28, the commander of Ukraine’s ground forces described the situation as “extremely tense.” Russian troops, including Wagner units, are attempting to cut Ukraine’s supply lines to the city in a bid to force troops to surrender or withdraw.

On February 28, pro-Russia sources shared a video showing Russian Su-25 fighter jets deployed over Bakhmut. The lack of adequate air support has been among the primary sources of friction between the Russian General Staff and the units fighting in Bakhmut. Footage from Ukraine’s 93rd Separate Mechanized Brigade shows fighting escalating, but Ukrainian forces appeared to be holding off the advance at the time of writing. On February 27 and 28, Ukrainian soldiers repelled more than sixty attacks, including on the villages of Yahidne and Berkhivka, north of Bakhmut. According to a pro-Russia blogger’s Telegram channel, Wagner units are advancing north of Bakhmut, but Ukraine’s army has not retreated. Amid heavy fighting, Wagner reportedly advanced on February 27 towards the AZOM metallurgical plant in north Bakhmut.

Rybar, a Russian Telegram channel believed to be linked to the defense ministry, claimed on March 2 that Wagner’s troops had reached the western suburbs of Bakhmut and clashed with Ukrainian forces in the hills north of the area. According to Rybar, Russian troops approached the road between Chasiv Yar and Bakhmut. On March 2, The Insider reported that Bakhmut was under operative siege as Ukraine’s army repelled attacks in Orikhovo, Vasylivka, Dubovo, Khromove, and Ivanivske.

Meanwhile, NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg told a Helsinki summit on February 28 that the end of the war in Ukraine “would not lead to normalization” of relations with Russia.

—Ruslan Trad, Resident Fellow for Security Research, Sofia, Bulgaria

Volunteer Russian unit fighting for Ukraine reportedly infiltrates Bryansk

Russian government figures, Kremlin media, and pro-Russia Telegram channels are heavily focused on an alleged March 2 incursion by pro-Ukraine forces in the Russian village of Sushany, Bryansk oblast, approximately one kilometer away from Ukraine’s north-central border with Russia. DW News and Radio Free Europe reported that members of the Russian RDK volunteer corps crossed into Russia and were active in the Bryansk area at the time of publishing.

According to DW News, RDK is “a unit of volunteers from Russia who have been fighting on the side of Ukraine since August 2022.” Initially, Ukrainian authorities dismissed the claims of an insurgency in the Russian village as a Russian false-flag operation. However, a video published on the official RDK Telegram channel showed fighters holding the unit flag and indicating a Russian government building behind them. In the video, and later in follow-up interviews, members of the unit adamantly denied claims spread by Russia that they had attacked the civilian population. They stated that the infiltration into Russian territory was done to sabotage Russian military targets. Additional reporting confirmed that RDK leader Denis Nikitin appeared in the video.

Russian Telegram channels and media did not distinguish that the volunteer troops are of Russian origin; instead they reported that a group of “Ukrainian saboteurs” had infiltrated sovereign Russian territory. The governor of Bryansk announced on March 2 that “saboteurs” had attacked the civilian population, killed a man, and taken hostages. President Vladimir Putin described the incident as a “terrorist attack” and condemned the alleged unprovoked shelling of a civilian vehicle. The Kremlin said it was closely monitoring the situation and continued to label the alleged insurgents as “Ukrainian militants.” It also tasked the Federal Security Service with conducting counterterrorism operations in response to the situation in Bryansk.

Russia also suggested that the Center of the Psychological Operations of the Ukrainian Armed Forces (Центринформационно-психологических операций ВСУ) may have been responsible for the “attacks on civilians and infrastructure” in Bryansk, again making no distinction between the RDK and the official Ukrainian military. Echoing the Kremlin’s “terrorism” claim, far-right nationalist State Duma member Aleksey Zhuravlyov labeled the Ukrainian military and political leadership as “terrorists” in official public statements and called for an escalation of the “special military operation” into open war.

As the conflict along the eastern flank intensifies, escalatory narratives involving northern regions of Ukraine could serve as a critical Kremlin tool for conducting operations into the northern border, where Russian forces could tap into already stationed and mobilized Belarusian troops, military bases, and equipment, along with their own units left behind following joint military training exercises between Russia and Belarus.

—Kateryna Halstead, Research Assistant, Bologna, Italy

Kremlin-linked Telegram networks coordinated to spread disinformation around the world

The DFRLab recently discovered fifty-six pro-Kremlin Telegram channels that targeted twenty countries with pro-Kremlin disinformation. Three networks of similarly named accounts — Surf Noise, Info Defense, and Node of Time — targeted users worldwide, including in Europe, Asia, South America, and the Middle East. The operation primarily relied on volunteer work. It focused on translating and spreading pro-Russia disinformation, as well as amplifying reports from Kremlin media outlets, state organizations, and state actors.

The DFRLab found clear coordination between the three networks, but the approach to capturing a global audience was unsophisticated. The DFRLab consulted its global team of researchers to examine the accuracy of translations and found that the quality of translations was poor.

—Nika Aleksejeva, Research Fellow, Riga, Latvia

—Sayyara Mammadova, Research Assistant, Warsaw, Poland

Report examines Russia’s decentralized approach to internet censorship

Russian digital rights organization Roskomsvaboda collaborated with the Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI) to publish a report examining “a year of military censorship in Russia.” The report reviews censored topics, websites, and services, as well as the legislative mechanisms used to enforce the censorship.

According to the report, Russia blocked 494 domains over the course of 2022. These fell into twenty-eight categories, with news media representing the largest category, followed by social networks, human rights organizations, and circumvention tools.

The report found that “more than 247,492 URLs were added to Roskomnadzor’s registry of banned websites” in the past year. However, the orders to ban content did not only come from Russia’s internet regulator. Other Russian agencies that requested websites be blocked include the federal tax service, Russian courts, and the prosecutor general’s office, among others. The report’s authors found over 3,500 instances of an entity anonymously requesting a website block.

While blocking requests are centralized through Roskomnadzor’s registry, the implementation of internet censorship in Russia is decentralized, the report concluded. The authors found forty-eight of the 494 blocked domains were absent in Roskomnadzor’s registry. The report suggested that some internet providers in Russia can block content not listed in Roskomnadzor’s registry.

—Eto Buziashvili, Research Associate, Tbilisi, Georgia